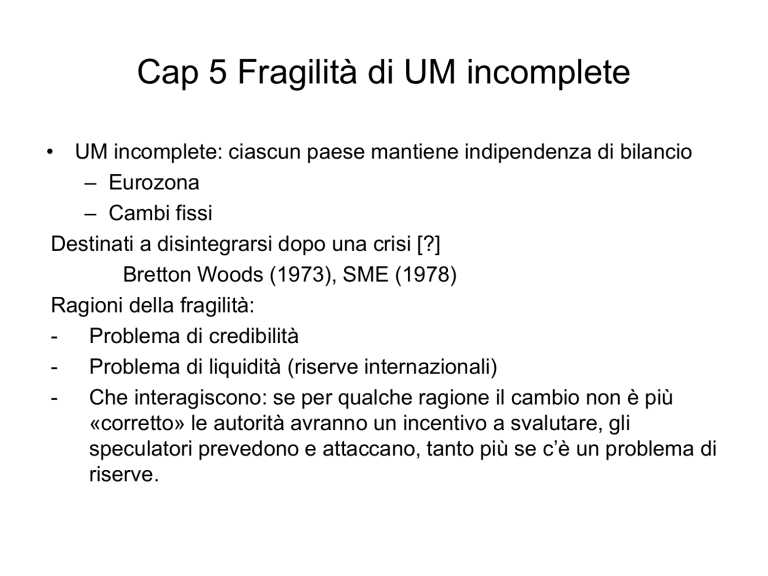

Cap 5 Fragilità di UM incomplete

• UM incomplete: ciascun paese mantiene indipendenza di bilancio

– Eurozona

– Cambi fissi

Destinati a disintegrarsi dopo una crisi [?]

Bretton Woods (1973), SME (1978)

Ragioni della fragilità:

- Problema di credibilità

- Problema di liquidità (riserve internazionali)

- Che interagiscono: se per qualche ragione il cambio non è più

«corretto» le autorità avranno un incentivo a svalutare, gli

speculatori prevedono e attaccano, tanto più se c’è un problema di

riserve.

Modello

• Disavanzo dei conti con l’estero

aumento l’indebitamento con l’estero

• Prima o poi deve essere corretto

• Due modi:

– Riduzione della domanda interna (costoso

politicamente)

– Svalutazione (si assume meno costoso)

Costi e benefici di una svalutazione:

modelli di prima generazione

Costi e benefici di una svalutazione:

modelli di prima generazione

• Se ε > ε0 cioè se lo shock è grande, il beneficio della

svalutazione supera il costo, ci sarà dunque la

tentazione di svalutare,

• La speculazione prevede la mossa,

attacca precipitando la svalutazione

La ragione della crisi sta nel tentativo delle autorità di

perseguire obiettivi inconciliabili.

La speculazione accelera semplicemente quello che

dovrebbe accadere [ma può anche far accadere quello che

avrebbe potuto essere evitato]

Modelli di seconda generazione: equilibri

multipli

• Distinzione fra svalutazione attesa e inattesa

• BU-curve : benefit of devaluation when

devaluation is not expected

• BE-curve : benefit of devaluation when

devaluation is expected (=speculative attack)

• BE > BU because when devaluation is expected

the defence of the fixed rate is very costly

(central bank has to raise interest rate with

negative effect on economy)

Tre shocks

• a small shock: ε < ε1 ;

– no devaluation because the cost exceeds the

benefits

– Speculators know this

– They do not expect devaluation

– Expectations consistent with outcome of

model

– Fixed exchange rate credible

• large shock ε > ε2

– devaluation is certain

– because the benefits exceed the cost.

– the fixed exchange rate is not credible

– expectations are model consistent

• intermediate shock: ε1<ε < ε2.

– Two possible equilibria, N and D

– In N: speculators do not expect devaluation;

as a result cost > benefit; no devaluation

occurs

– In D: speculators expect devaluation; as a

result cost < benefit; devaluation occurs

– The selection of these two equilibria only

depends on state of expectations

– Self-fulfilling prophecy: It is sufficient to expect

a devaluation for this devaluation to occur.

Nota Importante

• The existence of two equilibria ultimately depends on the

fact that the central bank has a limited stock of

international reserves. [o libertà di movimento di capitali]

• Suppose the central bank had an unlimited stock of

international reserves.

• In that case, when a speculative attack occurs

(speculators expect a devaluation), the central bank

would always be able to counter the speculators by

selling an unlimited amount of foreign exchange.

• The central bank would always beat the

speculators.

• The latter would know this and would not

start a speculative attack.

• In other words they would not expect

devaluation.

• The BE curve would coincide with the BUcurve.

• There would be no scope for multiple

equilibria.

• Ruolo dei movimenti di capitali

• Currency board

UM senza unione fiscale

• UM incompleta:

• Un’autorità monetaria (BCE) e autorità

nazionali indipendenti (che fissano bilancio

e debito)

• Il debito è emesso in una moneta che non

possono controllare

• La speculazione passa dal cambio ai

titoli del debito pubblico

Modello semplice

• Costi e benefici del default

• Gli investitori lo sanno

• Shock: riduzione delle entrate (es.

recessione o perdita di competitività)

• De Grauwe lo definisce uno shock di

solvibilità

Benefits of default

Figure 5.3 The benefits of default after a solvency shock.

benefits

• Benefit of default:

• Government reduces

interest burden;

• Cost of taxation

reduced

• Benefit increases with

size of solvency shock

• And size of govt debt

Solvency shock

Cost and benefit of default

Figure 5.4 Cost and benefits of default after a solvency shock

Cost arises because of loss of reputation and thus difficulties

to borrow in the future

Three types of shocks

Figure 5.5 Good and bad equilibria

Small shock: S < S1

There will be no default because

cost exceeds benefits,

Consistent with expectations

Large shock: S > S2.

Default is certain because benefits

exceed costs

Consistent with expectations

Intermediate shock:

S1 < S < S 2

Two equilibria: N and D

Both consistent with expectations

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

Equilibri multipli

• Per valori dello shock intermedi, possiamo avere

due risultati (D o N)

• The selection of one of these two points only

depends on what investors expect.

– If the latter expect a default, there will be one;

– if they do not expect a default there will be none.

– This remarkable result is due to the self-fulfilling nature of

expectations.

• We have coordination failure

Se il risultato è default

• Crisi bancaria

• Fuga dai titoli i aumenta e i P cadono

perdite in c/K delle banche

• Si interrompe il flusso del credito: problemi di

finanziamento delle banche (la liquidità

scompare)

• La crisi del debito si trasforma in crisi bancaria

Gli stabilizzatori automatici vengono

neutralizzati

• La recessione (e la crisi) aumenta il disavanzo

speculazione contro i titoli necessità di politiche di

austerità in recessione

• Stesso meccanismo dei PVS: impossibilità di usare il

bilancio pubblico per stabilizzare il ciclo (aggravando il

ciclo)

• Fuori da UM il governo può contare sulla BC, da questo

dipende la possibilità di due equilibri

Case study: From liquidity crises to

forced austerity in the Eurozone

• Two topics

• Empirical evidence: strong increases in the

government bond spreads in the Eurozone

since 2010 :

– were not only due to deteriorating fundamentals (e.g.

government budget deficits and debt levels)

– but were driven mainly by market sentiments (i.e. by

panic and fear).

• The ensuing spreads forced countries into

severe austerity measures that in turn led to

increasing government debt to GDP ratios.

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

Positive relation between Government debt and spreads

But sudden burst from 2010 that cannot be explained by increase in debt

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

Estimated from econometric equation linking spreads with whole series of

fundamental variables

Time component is proxy for market sentiments (fear and panic)

Greece: mostly fundamentals’ driven; other countries: mostly market sentiments

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

• How did the surge in the spreads that (as we

showed) were mostly related to market

sentiments affect the real economy?

• This is the question of how these spreads and

the ensuing liquidity problems forced the

governments of these countries into austerity

Figure 5.8 Austerity measures and spreads in 2011.

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

Interpretation

• Increasing spreads due to market panic,

these increases gripped policy makers.

• Panic in the financial markets led to panic in

the world of policymakers in Europe.

• As a result of this panic, rapid and intense

austerity measures were imposed on

countries experiencing these increases in

spreads.

• How well did this panic-induced austerity

work?

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

Figure 5.9 Austerity (2011) and GDP growth (2011–12).

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

Figure 5.10 Austerity (2011) and increases in government

debt–GDP ratios (2010IV–2012III).

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

Conclusion

• In this chapter we have analyzed the inherent

fragility of incomplete monetary unions.

• We focused on two incomplete monetary unions,

– i.e. a fixed exchange rate regime and

– a Eurozone-type incomplete monetary union.

• Both types of unions are characterized by a similar

fragility.

• In both cases, a lack of confidence can in a selffulfilling way drive the country to a devaluation (in

the first case) or to a default (in the second case.

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

• fragility is problematic because it leads to

questions of sustainability of incomplete

monetary unions.

De Grauwe: Economics of Monetary Union 9e

Crisi autorealizzantesi

•

•

•

•

•

Crisi di credibilità

aumento spreads

Austerità

Riduzione crescita del PIL

Aumento debito/PIL

Come rendere la UM sostenibile?

– Accrescere i costi dell’insolvenza (espulsione dei

paesi inadempienti)

– Prestatore di ultima istanza della BCE

– Consolidare i debiti nazionali in un unico debito

comune

• Come eliminare il circolo vizioso debito

sovrano-banche?

– Unione bancaria: ripartisce su tutti la crisi di un paese

Grexit

• La bolla?

– Tasso di crescita del PIL sostenuto

– Debito pubblico/PIL non si riduce

– Indebitamento pubblico e privato (credit push)

– Differenziale di inflazione (CLUP relativi)

• La crisi

– Sudden stop: rientro dei capitali bancari

– Crisi del debito sovrano e delle banche:

condizionalità dei prestiti

– Austerità, de-levereging, svalutazione interna:

caduta del reddito e aumento debito/PIL

Costi e benefici della Grexit

• Grecia:

– default sul debito, con implicazioni sulla solvibilità del sistema

bancario (e sui risparmi privati e istituzioni previdenziali)

– Svalutazione: aumento di competitività ma rischi di spirale

inflazionistica

• Resto dell’UME

– Rischio contagio e credibilità: al prossimo shock, chiunque può

uscire

– Riduzione dell’esposizione netta delle imprese verso altri paesi,

per timore di potenziali perdite in caso di uscita e

ridenominazione in valuta nazionale

•

L’uscita renderebbe il resto dei paesi con una struttura

più uniforme, migliorando la convergenza?