Vol. 3° ­ XIII.

PIGMENTAZIONE DELLA CUTE

Introduzione

La pigmentazione di tessuti diversi dalle piume coinvolge tanto i carotenoidi che le melanine. Il

carotenoide più importante è la xantofilla, che spesso condivide la stessa area di distribuzione

delle melanine, dando luogo a svariati fenotipi, tra i quali possiamo citare tarsi gialli, bianchi,

verdi e blu. La deposizione di ambedue i tipi di pigmento è influenzata da geni specifici cui si

associano spesso geni modificatori non ancora identificati.

La presenza, o l’assenza, di uno o dell’altro, o di ambedue i pigmenti, è in grado di produrre

una sorprendente varietà di colorazione dei tarsi, dovuta al fatto che esistono due differenti

settori in cui i pigmenti possono depositarsi: l’epidermide, più esterna, e il derma, su cui

poggia l’epidermide. La tabella che segue sintetizza le 9 possibilità. Indichiamo con il segno l’assenza di pigmento.

Colore dei tarsi a seconda del pigmento epidermico e dermico

il segno ­ indica assenza di pigmento

epidermico

dermico

colore dei tarsi

-

nero

giallo

bianchi

blu ardesia

paglia

nero

nero

nero

nero

giallo

bianco sporco

neri

giallo sporco

giallo

giallo

giallo

nero

giallo

paglia

verdi

gialli

La colorazione dei tarsi non dipende solo da fattori genetici. Bisogna tener conto del fatto che

ne è responsabile anche l’età del soggetto. Infatti, al momento della schiusa, il colore dei tarsi

è un dato inaffidabile per prevedere la colorazione adulta. Per fare un esempio, tarsi gialli alla

nascita possono colorarsi in bianco o in verde nell’età matura. Pulcini di 4 settimane d’età con

tarsi verdi, da adulti possono presentare tarsi blu ardesia. Col passare degli anni l’intensità della

colorazione si affievolisce, cosicché si può passare a tarsi color paglia oppure grigio tenue.

Bisogna pertanto far attenzione a non pretendere, come vuole lo standard, una colorazione dei

tarsi di uguale entità in soggetti di età differente: essi non possono competere per puri motivi

fisiologici.

La dieta ha spesso un peso non indifferente, in quanto con l’apporto di carotenoidi, contenuti

nell’erba e nel granoturco, si ottiene spesso un’intensificazione del giallo. Un cattivo stato di

salute, nonché malattie specifiche, come la coccidiosi , tendono a far impallidire i tarsi gialli.

A costo di risultare pedante, i giudici si ricordino di interessarsi se una femmina, con occhi e

tarsi poveri in carotenoidi, sia ammalata oppure un’ottima fetatrice.

1. PIGMENTAZIONE DA CAROTENOIDI

I carotenoidi sono responsabili della colorazione gialla della pelle, dei tarsi, del becco, del

tessuto adiposo, del tuorlo e talora dell’occhio. Sono punti già trattati nel capitolo dedicato a

questi pigmenti di origine vegetale. Vogliamo rammentare che, diversamente da quanto accade

nei Canarini, nei Parrocchetti, nei Fenicotteri , i carotenoidi non rivestono alcuna importanza

pratica nella pigmentazione del piumaggio del pollo.

La xantofilla è pure presente nei cromatofori dell’iride, dove, combinandosi con il colore rosso

del letto capillare, causa la colorazione che va sotto il nome di occhio baio.

La colorazione gialla della cute è un tratto caratteristico di Livorno, Plymouth Rock, Cornish,

Rhode Island, Brahma e Cocincina. Invece, Orpington, Dorking, Sussex, Langshan e Minorca

non posseggono carotenoidi cutanei neppure ai tarsi.

1.1. Pelle bianca autosomico

W+ ­ white skin

Autosomico dominante Gruppo di associazione III ­ cromosoma 1

Per chi avesse ancora qualche problema con la lingua che ha assunto il ruolo di esperanto, W sta

per l’inglese white, bianco. Questo gene è attribuito al Gallo Rosso della giungla, nel quale

inibisce la deposizione di xantofilla a livello della cute, dei tarsi e del becco, mentre iride, tuorlo

e sangue contengono una normale quota di carotenoidi. Nelle razze in cui il gene melanina

dermica id+ è presente, i tarsi sono blu ardesia.

1.2. Pelle gialla

w ­ yellow skin

Autosomico recessivo Gruppo di associazione III ­ cromosoma 1

Allele del precedente. La cute gialla o bianca può essere identificata con sicurezza solo all’età di

10-12 settimane e la diagnosi viene complicata dalla dieta, in quanto, se è povera in

carotenoidi, può causare una cute paglierino pallido anche se il soggetto è geneticamente w/w.

Gli omozigoti w/w presentano cresta, bargigli e orecchioni che, quando sono rossi, hanno una

tonalità arancio molto sostenuta, in quanto la xantofilla si sovrappone al rosso. Nelle stesse

circostanze gli orecchioni, qualora geneticamente bianchi, assumono una spolveratura

zafferano. Se è presente il gene melanina dermica id+, i tarsi sono verde oliva.

Le variazioni d’intensità del giallo a carico dei tarsi viene influenzata anche da fattori genetici e

dal sesso d’appartenenza. Soggetti di una stessa razza che ricevono la stessa razione possono

differire in modo significativo e di norma i maschi hanno tarsi più gialli rispetto alle femmine.

Tra le cause di natura genetica vengono inclusi, oltre a geni modificatori sconosciuti, anche

concause legate al sesso, tra cui potrebbe essere annoverato il gene B che è in grado di

schiarire i tarsi gialli. Quest’osservazione, dovuta a Jaap, si basa su un soggetto bianco

columbia e successivamente tale studioso ha potuto stabilire che l’effetto è dose dipendente.

Identification of the Yellow Skin gene reveals

a hybrid origin of the domestic chicken

1.3. Pelle bianca legato al sesso

y ­ sex linked white skin

Legato al sesso, recessivo Gruppo di associazione V ­ cromosoma Z

La sua azione consiste nell’eliminare la xantofilla dai tarsi e dalla cute, mentre il tessuto

adiposo addominale e il tuorlo sono gialli. Bisogna sottolineare tuttavia che il tuorlo delle

femmine y_W+ risulta più pallido rispetto al genotipo Y+_W+ o W+/W+. Allo stesso modo si

riscontra una riduzione del livello plasmatico di xantofilla nei soggetti omozigoti_emizigoti per

y.

Il fenotipo a pelle bianca dovuto al gene legato al sesso y può essere accuratamente

determinato nei pulcini appena nati, mentre ciò non accade nel genotipo autosomico W+/W+.

1.4. Testa gialla

g ­ yellow head

Autosomico recessivo Gruppo di associazione sconosciuto

Questa mutazione determina, già a poche settimane di vita, un’accentuazione della colorazione

gialla delle parti vascolarizzate dei seguenti distretti: faccia, cresta, bargigli. Questa situazione si

accentua prima del raggiungimento della maturità sessuale, dopo di che i maschi si avvicinano

pian piano alla colorazione rossa abituale, mentre le femmine in periodo depositivo presentano

una tinta rosa tenue. Il genotipo g/g non ha alcun effetto sulla pelle bianca di origine

autosomica W+. Si presume che questa anomalia sia il risultato di un’interferenza con la

normale vascolarizzazione dei tessuti interessati.

2. PIGMENTAZIONE DA GUANINA

Abbiamo già parlato dell’argomento nel paragrafo dedicato a questa sostanza (vol.II XXIX.2), che nel pollo è presente solo a livello degli orecchioni. Nello stesso paragrafo

abbiamo anche riportato tutto ciò che è disponibile circa la genetica del tratto faccia bianca

caratteristico della Spagnola

. Si rammenta che la colorazione bianca degli orecchioni

sembra comportarsi come tratto poligenico.

Un'ottima e accurata disamina, accompagnata da una pregevole documentazione iconografica,

dal titolo Ears and earlobes - Orecchie ed orecchioni - è stata curata da Elly Vogelaar ed è

reperibile nel web grazie al sito olandese Aviculture Europe.

3. PIGMENTAZIONE DA EUMELANINA

La melanina di tutti i distretti diversi dal piumaggio è solo eumelanina, in quanto la

feomelanina si riscontra solo nelle piume. L’eumelanina si trova nelle seguenti strutture

anatomiche: epidermide, derma, occhio, mesentere, peritoneo, testicolo, avventizia dei vasi

sanguigni, connettivo della fascia strettamente adesa alla superficie esterna dei muscoli

addominali superficiali. La sua presenza o la sua assenza dipendono dal genotipo, con assenza

totale nell’albinismo recessivo o autosomico, ca, tirosinasi negativo, in quantità estrema nel

genotipo fibromelanotico il cui prototipo è rappresentato dalla Silky.

3.1. Melanina epidermica

Generalmente l’epidermide del pollo contiene scarsissimi eumelanociti, se si eccettuano le

palpebre del soggetto normale e le aree della testa nel fenotipo faccia da zingaro o faccia di mora.

I geni maggiormente responsabili dell’eumelanizzazione epidermica sono due: quello

dell’estensione del nero E, e quello del bruno dorato ER che è meno efficace. Gli effetti di E

sono più evidenti a livello dei tarsi e, se mancano certi geni inibitori dell’eumelanina, spesso le

zampe sono nere. I tarsi neri dovuti al genotipo E/E riescono a conservare un po’ di

pigmento nel derma pur in presenza del gene inibitore della melanina dermica Id. Gli effetti di

ER vengono inibiti con più facilità.

L’inibitore più potente della melanina epidermica ai tarsi è il bianco dominante I, il quale,

come sappiamo, è in grado di impedirne la deposizione anche a livello delle piume. Anche i

geni del barrato autosomico B e del pomellato mo sono in grado di inibire la deposizione di

melanina nell’epidermide dei tarsi. Qualora si tratti di pomellati eumelanotici, i tarsi sono

bianco rosato oppure gialli a seconda del genotipo relativo alla deposizione di carotenoidi, con

piccole squame epidermiche residue nere o grigie.

L’effetto di B è dose dipendente, per cui, qualora si faccia imperativo il desiderio di ottenere

maschi con barratura femminile, si deve pagare il fio di tarsi più scuri e di becco anch’esso

scuro, mentre ciò non accadrebbe per un maschio omozigote.

Abitualmente si considera il gene del melanismo Ml come dotato di azione esclusiva sul

piumaggio. Dopo osservazioni di Ab-Der-Halden questo gene è pure responsabile della

presenza di melanina epidermica e questo permette di spiegate le diverse tonalità di grigio ai

tarsi. Se il gene del melanismo fa parte del patrimonio di un barrato legato al sesso, i tarsi

tenderanno a non avere melanina epidermica, poiché a questo livello il gene B inibisce Ml.

La melanizzazione epidermica della faccia, della cresta e dei bargigli è caratteristica del fenotipo

faccia da zingaro o faccia di mora, presentato da Sumatra, Combattente Inglese Moderno

con genotipo ER con o senza aggiunta di argento; lo stesso fenotipo, seppure in grado minore,

lo possiede anche la Sebright. La conferma che in questo fenotipo entra in gioco la melanina

epidermica proviene dalle osservazioni degli allevatori, i quali hanno notato che la faccia si

abbronza ulteriormente con l’esposizione al sole. Nel 1987 Auclair non riuscì a intensificare la

pigmentazione di questo distretto ricorrendo ai soli raggi ultravioletti in soggetti con

eumelanina a livello dermico, quelli cioè dotati del gene id+, e non riuscì nel suo intento

neppure nei fibromelanotici.

Dal momento che questi fenotipi a faccia scura sono spesso dotati del gene E oppure del gene

ER, potrebbe darsi che la causa risieda in tali alleli o in qualche allele similare. Tuttavia,

parecchi fenotipi legati a E, nonché a ER, hanno una bella faccia rosso brillante priva di

melanina epidermica, e lo stesso accade anche in quelli che hanno la melanina dermica legata a

id+. Allo stato attuale delle conoscenze non si può affermare se il fenotipo faccia da zingaro sia

dovuto a un allele del locus E oppure a un gene modificatore dotato di dominanza rispetto ai

geni E ed ER.

3.2. Melanina dermica

Nonostante nei distretti cutanei diversi dai tarsi i melanociti dermici siano scarsi, la loro

presenza nel derma delle zampe è una caratteristica posseduta da molte razze.

L’eumelanizzazione del derma è sotto il controllo di geni portati dal cromosoma Z.

I tarsi blu ardesia, o grigio ardesia che dir si voglia, sono dovuti alla melanina dermica, non

accompagnata da melanina epidermica. Nei tarsi ardesia lo strato corneo epidermico, che è

chiaro, altera la tonalità del pigmento nero sottostante. Tra le razze a tarsi blu ardesia,

tralasciando il Gallo Rosso della giungla, possiamo elencare: Amburgo, Polish, Campine,

Fayoumi, Nana di Giava, Catalana fulva, Sultano.

Gli standard sono indispensabili, essi rappresentano una garanzia per la conservazione della

purezza, sono un baluardo contro il relativismo odierno, infondono sicurezza e speranza.

Tuttavia, i Giudici debbono essere relativisti, anche conciliatori se necessario, debbono

soprattutto essere dei naturalisti. Anche se non hanno avuto la fortuna di viaggiare in terre

lontane, debbono possedere una cultura che va al di là dei canoni imposti da persone barricate

dietro lo standard, all’affannosa ricerca di protezione contro insicurezze personali che non

hanno nessun legame con l’avicoltura.

Qualcuno dirà: eccolo qui il Corti, di nuovo a rompere i roglioni con i suoi voli pindarici intrisi

di filosofia disfattista.

Non si tratta di disfattismo. A parte che a rimetterci le penne è il pollo, nel senso più che

letterale, e io il pollo voglio difenderlo, in quanto creatura programmata. Il disfattismo, nonché

l’accusa all’atteggiamento intransigente e assolutista, viene da Lewis Wright, il quale riferisce

come Mr Blyth avesse notato che la maggioranza dei Galli Rossi della sottospecie indiana

avessero tarsi blu plumbeo, mentre le sottospecie di Giava e della Malesia, rispettivamente

javanicus e spadiceus, presentassero una netta tinta giallastra, a distinct yellowish tinge.

È ovvio che non ho avuto l’onore di incontrare Sua Maestà nel suo habitat. È comunque

possibile organizzare una gita federale di verifica, con Soci disposti ad autofinanziarsi.

Lo stesso discorso sulla variabilità del colore dei tarsi può essere applicato al Phoenix. Ricordo

che agli inizi della mia carriera d’allevatore non esisteva parere concorde sulla colorazione dei

tarsi di questa razza, in quanto c’era chi li accettava gialli, chi invece li voleva ardesia. La

genetica è storia, per cui il motivo di questa altalena ce lo spiega il Pascal : “I tipi importati

per lo passato dal Giappone non avevano caratteri fissati, così si ebbero individui a cresta

riccia, altri a cresta scempia [semplice, NdA], nel contempo taluni avevano tarsi e becco gialli,

altri li avevano verdognoli o grigi, e lo stesso vale per le forme e pel mantello.”

Scorrendo sia l’American Standard of Perfection sia lo standard dell’American Bantam Association,

non esistono dubbi: i tarsi del Phoenix debbono essere plumbei. Lo standard olandese non

solo è più flessibile, ma pende dalla parte opposta, in quanto tarsi e dita possono essere blu

ardesia, o meglio, verde oliva scuro, presupposto genetico dei tarsi gialli - leiblauw of liever donker

olijfgroen. Relativismo? Flessibilità? Genetica? Cultura naturalistica? Forse tutto insieme. Gli

Olandesi spiccano per essere all’avanguardia nelle colorazioni, osteggiati da certi caporioni

tedeschi conservatori. Conservatori di che cosa? Una diatriba di questo tipo occuperebbe le

sedute dell’Entente Européenne per lustri, con la vittoria dei più nevrotici.

I tarsi verdi sono una caratteristica della Siciliana, nella quale il colore prende origine dalla

contemporanea presenza di carotenoidi, assenti nei tarsi ardesia.

3.3. Melanina dermica

id+ ­ dermal melanin

Legato al sesso, recessivo Gruppo di associazione V ­ cromosoma Z

Il gene responsabile della melanina dermica, dato per scontato nel Gallo Rosso della giungla, è

recessivo rispetto al suo allele mutante, capace invece di inibire l’eumelanogenesi in questo

distretto. Pertanto la sigla di questo gene inizia con la lettera i minuscola. La sua azione diventa

evidente a circa tre mesi d’età ed è indipendente dai geni che controllano la pigmentazione

dell’epidermide e del piumaggio. Infatti l’eumelanina dermica non viene eliminata né da I né da

c, anche se entrambi questi geni sono in grado di diluirla. Si conoscono altri inibitori di id+ :

barrato, pomellato, frumento dominante e recessivo, nonché Di. La presenza contemporanea

dei geni id+ e Ml dà un deposito di melanina dermica ed epidermica, con tarsi neri; se è

presente Bl i tarsi sono bluastri.

Nella regione francese di Bresse il gene id+ sembra essere responsabile degli addomi

naturalmente bluastri di certi polli. Gli inesperti considerano tale colore come un inizio di

putrefazione.

I Combattenti del Nord fuori standard, utilizzati nei gallodromi, posseggono molto spesso dei

tarsi verde oliva dovuti all’unione di id+ /id+ con w/w, e lo stesso colore si trova in ceppi di

Combattenti del Nord incrociati con Combattenti Belgi.

Mentre in Francia furono i tarsi gialli ad essere a lungo sinonimo di carne di cattiva qualità, in

Inghilterra sono i tarsi neri ad essere screditati. Sotto l’influenza francese gli Inglesi hanno

modificato le loro preferenze.

3.4. Inibitore della melanina dermica

Id ­ dermal melanin inhibitor

Legato al sesso, incompletamente dominante Gruppo di associazione V ­ cromosoma Z

La dominanza incompleta è dimostrabile dal fatto che i maschi eterozigoti mostrano una

pigmentazione melanica dei tarsi che è presente, ma debole.

Essendo legato al sesso, Id non può essere trasmesso dalla madre alle figlie, per cui questo

fatto potrebbe essere sfruttato per sessare ibridi la cui la madre è emizigote per Id e il padre è

omozigote per id+. I discendenti maschi presenteranno tarsi bianchi oppure gialli, mentre la

discendenza femminile sarà dotata di tarsi blu ardesia oppure verdi.

Gli studi più recenti hanno dimostrato che il locus Id possiede numerosi alleli. Le lettere in

sovrascritto indicano la razza o il ceppo dai quali è stata dedotta la presenza dei singoli alleli.

3.5. Melanina dermica Cornell

idc ­ Cornell randombred White Leghorn

Questa mutazione differisce dal selvatico id+ in quanto, pur trattandosi di una Leghorn con

genotipo I/I, il pigmento è presente sia nel piumaggio che nel becco. In questo stesso ceppo si

è potuto osservare che le femmine emizigoti per idc e dai tarsi verdi sono significativamente più

suscettibili agli emangiomi rispetto alle loro sorelle dai tarsi gialli, e quindi emizigoti per Id.

3.6. Melanina dermica Ancona

ida ­ Ancona

Questo allele permette ovviamente la deposizione di melanina dermica ai tarsi ed è stata

dedotta la sua esistenza nell’Ancona a causa di piccole chiazze verdi. Tuttavia i dati non sono

pienamente convincenti per ammettere l’esistenza di questo nuovo allele, in quanto il fenotipo

potrebbe spiegarsi o attraverso un’interferenza da parte di mo, oppure con l’intervento di geni

modificatori, oppure più semplicemente con il deposito di xantofilla a livello epidermico in

aree ristrette senza distribuzione uniforme, causa di evidenti grattacapi per gli allevatori di

questa razza tutta italiana.

3.7. Melanina dermica Massachusetts

idM ­ Massachusetts

Questa mutazione comparve in una linea derivata dall’incrocio tra Langshan nera e una linea

commerciale da carne dal piumaggio bianco dominante. Differisce dagli alleli precedenti per il

fatto di essere riconoscibile nei pulcini di un solo giorno di vita con genotipo E, ER, e+, nonché

nei pulcini con bianco recessivo. L’allele idM provoca i tarsi più neri quando la sua azione si

combina col gene E. Con un genotipo c/c_E/- il colore dei tarsi è talora diluito, ma è ancora

color ardesia intenso. Non si esprime nei genotipi bianco dominante, ma la combinazione I_E

dà come risultato un color ardesia o verde pallido all’età di 10-12 settimane.

3.8. Basi genetiche della colorazione dei tarsi

L’espressione fenotipica della colorazione delle gambe e dei piedi del pollo dipende dagli

effetti interattivi e cumulativi di alcuni geni maggiori con geni modificatori non identificati in

grado di accentuare o ridurre l’eumelanina.

Gli effetti dei geni id+ e Id rimangono confinati al derma, mentre l’effetto di E si svolge

soprattutto a livello epidermico, ma è anche in grado di aggiungere una quota variabile di

eumelanina al derma.

Il gene I è epistatico sulla melanina epidermica, ma a livello del derma riesce solo a diluire il

pigmento, non a eliminarlo. Anche il bianco recessivo è dotato di un’azione simile.

I geni B e mo sono i maggiori inibitori della melanina epidermica dei tarsi. In aggiunta a ciò,

l’assenza o la presenza dei carotenoidi (dovuta rispettivamente a W+ e a w) interagisce con

l’eumelanina del derma dando luogo a tarsi blu ardesia o verdi.

Nonostante i numerosi studi sulla genetica della colorazione dei tarsi, esistono ancora delle

variazioni che non hanno ricevuto una spiegazione esauriente.

Le deduzioni genetiche hanno delle tappe storiche che consistono dapprima nella scoperta dei

loci E e Id, con la dimostrazione che l’allele di estensione del nero E si associa a tarsi ben più

neri di quanto non accada con il genotipo ER. Tuttavia quest’ultimo gene può essere presente

in soggetti completamente neri se si associano i necessari geni intensificatori dell’eumelanina,

come Ml. Questo spiega perché esistano soggetti dal piumaggio completamente nero con

melanina appena presente o assente ai tarsi in quanto hanno un genotipo ER: se la melanina è

presente, essa è epidermica ed è dovuta all’effetto combinato di Ml e di ER.

Altro rompicapo è il riscontro di una tenue colorazione verde estesa a tutta la zampa o solo a

una parte, in apparente assenza del gene id+. Altra osservazione: il gene B elimina la melanina

dermica nei soggetti bianco dominante e bianco recessivo, ma la intensifica in presenza del

gene Co. Da ultimo, come già detto, il gene Co è capace di ridurre l’intensità dei tarsi gialli.

Interazioni in cui sono coinvolti i geni maggiori della pigmentazione

nel determinare la colorazione dei tarsi

carotenoidi

melanina

dermica

Id

W+

id+

Id

w

id+

melanina

epidermica

genotipo

fenotipo dei tarsi

E

W+ W+ Id Id EE

tarsi quasi neri con suole bianche

e+

E

W+ W+ Id Id e+ e+

gambe e piedi bianchi

W+ W+ id+ id+ EE

tarsi neri con suole nere

e+

W+ W+ id+ id+ e+

e+

tarsi ardesia con suole bianche

E

ww Id Id EE

tarsi quasi neri con suole gialle

e+

E

ww Id Id e+ e+

gambe e piedi gialli

ww id+ id+ EE

tarsi neri con suole gialle

e+

ww id+ id+ e+ e+

tarsi verdi con suole gialle

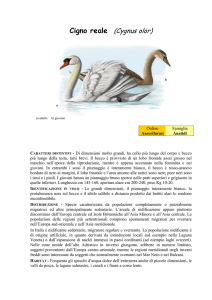

Tarsi verdi in femmina ibrida di genitori sconosciuti

foto Elio Corti ­ luglio 2007

3.9. I tarsi del Combattente Inglese Moderno Pile

Possedendo le basi genetiche della colorazione dei tarsi, è possibile fare una digressione pratica

e vedere cosa accade quando si vuol mantenere una buona colorazione pile nel Combattente

Inglese Moderno, il cui standard richiede tarsi gialli.

Se il pile viene continuamente accoppiato con soggetti dello stesso colore, si giunge al bianco

puro per l’omozigosi del bianco dominante I, per cui a un certo punto è d’obbligo accoppiare

un pile con un dorato o black red. Il dorato ha i tarsi verde oliva, e quindi è

omozigote/emizigote per id+ a seconda del sesso. Inoltre, è omozigote per w, che non è legato

al sesso. +

Maschio dorato

Femmina pile

w_id+ / w_id+

w_Id/ w_­

+

w_id / w_id = tarsi verde oliva

w_Id / w_­ = tarsi gialli

50% maschi con tarsi gialli w_id+/w_Id

50% femmine con tarsi oliva w_id+/w_­

gameti maschili

gameti femminili

w_Id

w_­

w_id+ w_Id/w_id+ w_­/w_id+

w_id+ w_Id/w_id+ w_­/w_id+

Maschio pile

Femmina dorata

w_id+ / w_Id

w_id+/ w_­

+

w_id / w_Id = tarsi gialli

w_id+ / w_­ = tarsi verde oliva

25% maschi con tarsi gialli w_id+/w_Id

25% maschi con tarsi oliva w_id+/w_id+

25% femmine con tarsi gialli w_Id/w_­

25% femmine con tarsi oliva w_id+/w_­

gameti maschili

gameti femminili

w_id+

w_­

w_id+ w_id+/w_id+ w_­/w_id+

w_Id

w_id+/w_Id w_­/w_Id

Dal successivo quadrato di Punnett risulterà evidente che per ottenere il 100% di discendenti

pile a tarsi gialli conviene accoppiare un gallo bianco omozigote per Id con una femmina

dorata.

Maschio bianco

Femmina dorata

w_Id / w_Id

w_id+/ w_­

w_Id / w_Id = tarsi gialli

w_id+ / w_­ = tarsi verde oliva

gameti femminili

100% soggetti pile con tarsi gialli w_id+

gameti maschili

w_­

w_Id w_id+/w_Id w_­/w_Id

w_Id w_id+/w_Id w_­/w_Id

Tutto quanto abbiamo appena esposto si riferisce al problema dei tarsi. Per cui, in pratica, per

ottenere il 100% di soggetti pile conviene partire con un gallo bianco e una gallina dorata: la

discendenza sarà tutta pile, essendo tutta eterozigote per I, e avrà i tarsi gialli.

3.10. Fibromelanosi

Fm ­ fibromelanosis

Autosomico incompletamente dominante Gruppo di associazione sconosciuto

Il caratteristico colore nero bluastro della pelle della Silky è dovuto a eumelanina dermica e

non epidermica, presente non solo nello strato immediatamente sottoepidermico ma anche nel

derma più profondo, il cosiddetto connettivo lasso. Il pigmento è ben rappresentato anche nel

peritoneo parietale e viscerale, nel periostio e nel pericondrio. Anche i vasi sanguigni e i nervi

non sfuggono all’iperpigmentazione, che avvolge queste strutture, e neppure il connettivo dei

visceri ne è esente.

Secondo le osservazioni di Stolle, nei primi otto giorni d’incubazione il numero di melanociti

presenti nel connettivo di una Silky e di una Livorno perniciata è pressapoco identico, dopo di

che nella Silky la quota di melanociti presenta un’impennata, mentre nella Livorno

soccombono e vengono fagocitati. L’incremento numerico si verifica anche se la cute della

Silky viene messa a vivere in un ambiente diverso, come dimostrato da innesti in embrione. È

stato Stolle (1968) a proporre il genotipo dei soggetti fibromelanotici, affermando che il

fenotipo risulta dall’interazione tra id+ e un intensificatore dotato di dominanza, al quale Hutt

aveva assegnato il simbolo Fm. In accordo coi dati di Stolle, la combinazione di questi geni dà

origine ai seguenti gradi di pigmentazione del connettivo:

Combinazione di geni

e intensità della pigmentazione del connettivo

locus Fm

Fm/Fm/fm+/fm+

fm+/fm+

locus Id

connettivo

id+_- oppure id+/ id+

Id_- oppure Id/id+_- oppure id+/ id+

Id_- oppure Id/-

molto scuro

poco pigmento

senza pigmento

senza pigmento

In passato altri ricercatori hanno riferito di notevoli variazioni circa l’entità della fibromelanosi,

il che suggerisce l’ipotesi che siano interessati alcuni geni modificatori capaci di cambiare

l’espressione fenotipica. Alcuni di questi geni possono essere in relazione con quelli

responsabili della colorazione del piumaggio, sebbene la Silky sia presente nelle colorazioni

bianca, nera, blu, grigio perla, fulva e selvatica. Essendo la dominanza di Fm parziale, il

risultato dell’incrocio tra Moroseta con altre razze deve essere studiato punto per punto. In un

incrocio con una gallina comune si ottenne, per così dire, un mosaicismo melanotico: becco,

gambe e piedi neri, con rimanente pelle bianca.

3.11. Fascia addominale pigmentata

Fascia addominale pigmentata

Complessa interazione tra geni noti e ignoti,

dominanza incompleta tra alcuni alleli.

La presenza di eumelanina nella fascia sottocutanea strettamente adesa alla superficie esterna

dei muscoli addominali superficiali non è ben accetta dal consumatore. Il pigmento può variare

da poche chiazze sino alla formazione di un manto che abbraccia anche la metà posteriore dei

due muscoli, con un colore che varia dal grigio chiaro al nero. È presente in ambedue i sessi,

anche se la sua incidenza è significativamente più elevata nelle femmine. Jaap (1958) notò che

spesso questa anomalia si associa con gli alleli del locus Id diversi da id+.

Le basi genetiche di questa eumelanizzazione coinvolge una serie di complicate interazioni tra

geni conosciuti e sconosciuti, nonché un rapporto di dominanza incompleta tra alcuni alleli. Il

gene I inibisce la pigmentazione della fascia, specialmente in presenza di E, di B, e forse anche

di S. L’effetto inibitore maggiore è determinato dall’associazione di I con B, piuttosto che da

questi due geni presi singolarmente.

I soggetti con genotipo E sono meno pigmentati rispetto a quelli con restrizione columbia,

mentre il gene B incrementa la pigmentazione nei portatori di Co, specie il suo allele Bsd.

I soggetti con più elevata pigmentazione sono quelli con genotipo e+ e eb, e non quelli con

genotipo E. Invece il gene eWh è un potente inibitore della pigmentazione della fascia

addominale.

Il bianco recessivo pare in grado di accentuare la melanina addominale, specie nei pulcini con

un piumino color fumo. Anche il gene id+, secondo le osservazioni di Kuit, è in grado di

determinare un marcato aumento della melanina fasciale.

In pratica, i dati suggeriscono che il genotipo più efficace nel determinare l’assenza di melanina

a livello della fascia addominale è il seguente: I_C+_eWh_B_S_Id. sommario top avanti XIII. PIGMENTATION OF THE SKIN

Introduction

The pigmentation of tissues different from the feathers involves both carotenoids and

melanins. The most important carotenoid is the xanthophyll, which often shares the same

distribution area of melanins, resulting in various phenotypes, among which we can quote

yellow, white, green and blue legs. The deposition of both pigments is influenced by specific

genes which often join modifiers genes not yet identified.

The presence or the absence, of one or of other, or of both pigments, is able to produce an

amazing variety of legs coloration, due to the fact that two different sectors exist in which the

pigments can settle: the epidermis, more external, and the derma, on which the epidermis

leans. The following table synthesizes the 9 possibilities. We point out with the sign - the

absence of pigment.

Color of legs

depending on epidermic and dermic pigment

the mark – points out the lack of pigment

epidermic

dermic

color of legs

-

-

white

black

black

black

yellow

yellow

yellow

black

yellow

black

yellow

black

yellow

slate blue

straw

dirty white

black

dirty yellow

straw

green

yellow

The coloration of legs doesn't depend only on genetic factors. We have to consider the fact

that also the age of the subject is responsible of the coloring. In fact, at hatching, the color of

the legs is an unreliable datum to foresee the adult coloration. As an example, yellow legs at

birth can turn white or green in mature age. Chicks 4 weeks old with green legs, when adult

can show slate blue legs. With years' elapsing the intensity of the coloration grows weak, so

that it is possible to pass on straw colored or faint grey legs. Therefore we have to watch out

for not pretending, as the standard expects, a coloration of the legs of identical degree in

subjects of different age: they cannot compete because of pure physiological reasons.

The diet often has a non indifferent weight, since with the input of carotenoids, contained in

grass and maize, an intensification of the yellow is often gotten. A bad state of health, as well

as specific illnesses as the coccidiosis, have the tendency to make the yellow legs to turn pale.

At the cost to be pedantic, the judges have to remember to ask if a female, with eyes and legs

poor in carotenoids, is either ill or a very good layer.

1. PIGMENTATION BY CAROTENOIDS

The carotenoids are responsible of the yellow color of skin, legs, beak, fat, yolk and

sometimes of the eye. They are subjects already discussed in the II volume, in the chapter

devoted to these pigments of vegetable origin. We want to remember that, otherwise from

what happens in Canaries, Parakeets, Flamingos, the carotenoids don't have any practical

importance in the pigmentation of chicken's plumage.

The xanthophyll is also present in the chromatophores of the iris, where, combining with the

red color of the capillary bed, produces the coloration called bay eye.

The yellow color of the skin is a characteristic trait in Leghorn, Plymouth Rock, Cornish,

Rhode Island, Brahma and Cochin. On the contrary, Orpington, Dorking, Sussex, Langshan

and Minorca don't have skin carotenoids neither in the legs.

1.1. Autosomal white skin

W+ ­ white skin

Autosomal dominant

III group of association ­ chromosome 1

W stands for white. This gene is attributed to the Red Jungle Fowl, in which it inhibits the

laying of xanthophyll in skin, legs and beak, while iris, yolk and blood contain a normal amout

of carotenoids. In the breeds in which the gene dermic melanin id+ is present, the legs are slate

blue.

1.2. Yellow skin

w ­ yellow skin

Autosomal recessive

III group of association ­ chromosome 1

Allele of the previous one. The yellow or white skin can be surely identified only at the age of

10-12 weeks and the diagnosis is complicated by the diet, since, if poor in carotenoids, can

cause a pale straw-yellow skin even if the subject is genetically w/w.

The w/w homozygous subjects show comb, wattles and earlobes that, when red, have a very

high orange tonality, being that the xanthophyll overlaps the red. In the same circumstances

the earlobes, if genetically white, take a saffron dusting. If the dermal melanin id+ gene is

present, the legs are olive green.

The yellow's variations of intensity in legs is also influenced by genetic factors and by the sex

of the subject. Subjects of the same breed receiving the same food ration can differ in a

marked way and usually the males have legs more yellow in comparison to females. Among

the causes of genetic kind are included, besides unknown modifier genes, also sex-linked

concomitant causes, among which could be counted the B gene (sex-linked barring) able to brighten the yellow legs. This observation, due to Jaap, is based on a white Columbia subject

and later this researcher has been able to establish that the effect is dose dependent.

Identification of the Yellow Skin gene reveals

a hybrid origin of the domestic chicken

1.3. Sex linked white skin

y ­ sex linked white skin

Sex linked, recessive

V group of association ­ chromosome Z

Its action consists in eliminating the xanthophyll from legs and skin, while the abdominal fat

and the yolk are yellow. Nevertheless we have to underline that the yolk of y_W+ females is

paler in comparison to the genotype Y+_W+ or W+/W+. In. the same manner in the subjects

homozygous_hemizygous for y we find a reduction of the plasmatic level of xanthophyll.

The white skin phenotype due to the sex-linked y gene can be carefully determined in just born

chicks, while this doesn't happen in the autosomal genotype W+/W+.

1.4. Yellow head

g ­ yellow head

Autosomal recessive

Group of association unknown

This mutation induces, already at few weeks of life, an accentuation of the yellow color of the

vascularized areas of the following districts: face, comb, wattles. This situation intensifies

before the attainment of the sexual maturity, and after the males slowly get closer the usual red

coloration, while the females in laying stage show a slim pink shade. The genotype g/g doesn't

have any effect on the white skin of autosomal origin W+. They supposes that this anomaly is

the result of an interference with the normal vascularization of the involved tissues.

2. PIGMENTATION BY GUANINE

We have already spoken about this matter in the paragraph devoted to this substance (vol.II XXIX.2), which in the chicken is present only in earlobes. In the same paragraph we have also

related all is available about the genetics of white face trait characteristic of the Spaniard. You

have to remember that the white coloration of earlobes seems to act as polygenic trait.

3. PIGMENTATION BY EUMELANIN

The melanin of all the districts different from plumage is only eumelanin, being that the

pheomelanin is present only in feathers. The eumelanin is present in the following anatomical

structures: epidermis, derma, eye, mesentery, peritoneum, testicle, adventitia of blood vessels,

connective of the band tightly clinging to the external surface of the superficial abdominal

muscles. Its presence or its absence depend on the genotype, with total absence in the

recessive or autosomal albinism, ca, tyrosinase negative, in extreme quantity in the

fibromelanotic genotype whose prototype is represented by Silky.

3.1. Epidermal melanin

The epidermis of the chicken generally contains very scarce eumelanocytes, with the exception

of the eyelids of normal subject and the areas of the head in the phenotype gypsy face or

blackberry face.

The genes more responsible of epidermal eumelanisation are two: E of the extension of black,

and that of golden brown ER which is less effective. The effects of E are more evident in tarsi

and, if certain eumelanin's inhibiting genes are missing, often the legs are black. The black tarsi

due to the genotype E/E succeed in also preserving some pigment in the derma in presence

of dermic melanin inhibiting gene Id. The effects of ER are inhibited with more facility.

The most powerful inhibitor of the epidermal melanin in legs is the dominant white I, which,

as we know, is able to prevent its deposition also in feathers. Also the genes of the autosomal

barred B and of the speckled mo are able to inhibit the deposition of melanin in the epidermis

of the legs. If they are eumelanotic speckled, the legs are rosy white or yellow depending from

the genotype related to the deposition of carotenoids, with small black or grey residual

epidermal scales.

The effect of B is dose dependent, then, if the desire to get males with female barring is

imperative, you have to pay the penalty for darker legs and dark beak too, while this would not

happen for an homozygous male.

Usually the Ml gene of melanism is regarded as endowed with exclusive action on plumage.

After observations of Ab-Der-Halden this gene is also responsible of the presence of

epidermal melanin and this allows to explain the different tonalities of grey in legs. If the gene

of melanism is in the patrimony of a sex-linked barred, the legs will have the tendency to not

have epidermal melanin, since in this area the gene B inhibits Ml.

The epidermal melanisation of face, comb and wattles is characteristic of the phenotype gypsy

face or blackberry face, showed by Sumatra, Modern English Game with genotype ER with or

without silver addition; the same phenotype, even though in smaller degree, also by the

Sebright is possessed. The confirmation that in this phenotype the epidermal melanin is

involved comes from the observations of the breeders, who observed that the face further

tans with the exposure to the sun. In 1987 Auclair didn't succeed in intensifying the

pigmentation of this district resorting only to ultraviolet rays in subjects with dermal

eumelanin, that is those endowed with the gene id+, and he didn't even succeed in his intent in

fibromelanotic subjects.

Being that these phenotypes with dark face are often endowed with the gene E is or the gene

ER, could give that the cause resides in such alleles or in some similar allele. Nevertheless,

quite a lot of phenotypes tied to E, as well as to ER, have a beautiful bright red face devoid of

epidermal melanin, and the same also happens in those having the dermal melanin due to id+.

At present knowledge cannot be affirmed either the phenotype gypsy face is due to an allele

of the locus E or to a modifier gene endowed with dominance towards the genes E and ER.

3.2. Dermal melanin

Nevertheless in the skin districts different from legs the dermal melanocytes are scarce, their

presence in the derma of the legs is a characteristic possessed by a lot of breeds. The

eumelanisation of the derma is under the control of genes brought by the chromosome Z.

The slate blue or slate grey legs, as we want to call them, are due to dermal melanin, not

accompanied by epidermal melanin. In slate legs the epidermal horny layer, which is clear,

alters the tonality of the underlying black pigment. Among the breeds with slate blue legs,

skipping the Red Jungle Fowl, we can list: Hamburg, Polish, Campine, Fayoumi, Dwarf of

Java, Buff Catalan, Sultan.

The standards are essential, they represents a guarantee for the maintenance of the purity, they

are a rampart against the today's relativism, they infuse surety and hope. Nevertheless, the

Judges have to be relativist, also conciliatory if necessary, above all they have to be naturalists.

Even if they didn't have he fortune of travelling in far lands, they must possess a culture going

beyond the canons imposed by people barricaded behind the standard, in a breathless search

of protection against personal insecurities that don't have any bond with the aviculture.

Someone will say: here is Corti, newly pain in the ass with his Pindaric flights soaked with

defeatist philosophy.

It is not defeatism. Apart that to lose the feathers is the chicken, in the most literal meaning,

and I want to defend the chicken, as programmed creature. If somebody would like to accuse

me of defeatism against poultry judges and also against their intransigent statements, I have

the support of Mr Blyth quoted by Lewis Wright, who reports as Mr Edward Blyth had

noticed that the majority of Red Jungle Fowls of Indian subspecies had leaden blue legs, while

the subspecies of Java and Malaysia, respectively javanicus and spadiceus, were showing a clean

yellowish colour, a distinct yellowish tinge. The affirmations of Blyth must lead us to be not

absolutist at all in our affirmations, as often contained in poultry standards.

This means that we can discuss until nausea about the correct leg color in Gallus gallus. But

since all mentioned wild species are known today as being ancestors of our domesticated

chickens, we do have to accept the variability in leg color.

The same discourse on the variability of the color of legs can be applied in the Phoenix. I

remember that at the beginnings of my breeder career there didn't exist the same opinion

about the coloration of the legs of this breed, since there was who accepted them yellow, who

on the contrary wanted them slate. The genetics is history, then the reason of this wavering is

explained in Le razze della gallina domestica (1905) by Teodoro Pascal : "The types imported in

past times from Japan didn't have fixed characters, so we had individuals with curly comb,

others with single comb, at the same time some had yellow legs and beak, others had them

greenish or grey, and the same is for the shapes and the mantle."

Glancing both the American Standard of Perfection and the standard of American Bantam

Association, doubts don't exist: the legs in the Phoenix must be leaden. The Dutch standard is

not only more flexible, but it hangs in the opposite side, since legs and digits can be slate blue,

or better, dark olive green, genetic precondition of the yellow legs - leiblauw of liever donker

olijfgroen. Relativism? Flexibility? Genetics? Naturalistic culture? Perhaps all together. The

Dutch people stand out for being in the forefront about the colorations, opposed by certain

conservative German ringleaders. Conservatives of what? A diatribe of this type would occupy

the sessions of the Entente Européenne for lustres, with the victory of the more neurotic persons.

The green legs are a characteristic of Sicilian Buttercup, in which the color takes origin from

the contemporary presence of carotenoids, absent in the slate legs.

3.3. Dermal melanin

id+ ­ dermal melanin

Sex linked, recessive

V group of association ­ chromosome Z

The gene responsible of the dermal melanin, taken for granted in the Red Jungle Fowl, is

recessive in comparison to its mutant allele, able on the contrary of inhibiting the

eumelanogenesis in this district. Then the abbreviation of this gene begins with the lower case

letter i. Its action becomes evident at about three months of age and is independent from the

genes controlling the pigmentation of epidermis and plumage. In fact the dermal eumelanin is

not eliminated neither by I nor by c genes, even if both these genes are able to dilute it. They

are known other inhibitors of id+ : barred, speckled, dominant and recessive wheaten, as well as

Di. The contemporary presence of the genes id+ and Ml it gives a deposit of dermal and

epidermal melanin, with black legs; if the gene Bl is present the legs are bluish.

In the French region of Bresse the gene id+ seems to be responsible of the naturally bluish

abdomens of certain chickens. The inexperienced people consider such color as a beginning of

putrefaction.

The Fighters of the North (Fighters of the North, French Game Fowl) out of standard, used

in the gallodromes, very often have olive green legs due to the union of id+/id+ with w/w, and

the same color is found in strains of Fighters of the North crossed with Belgian Fighters.

While in France have been the yellow legs to be for a long time synonymous of meat of bad

quality, in England they are the black legs to be discredited. Under the French influence the

English people have modified their preferences.

3.4. Inhibitor of dermal melanin

Id ­ dermal melanin inhibitor

Sex linked, incompletely dominant

V group of association ­ chromosome Z

The incomplete dominance is demonstrable from the fact that the heterozygous males show a

melanic pigmentation of legs which is present, but weak.

Id, being sex-linked, cannot be transmitted from mother to daughters, then this fact could be

exploited for sexing hybrids whose mother is hemizygous for Id and the father e is

homozigous for id+. The male descendants will show white or yellow legs, while the female

descent will be endowed with slate blue or green legs.

The most recent studies have shown that the locus Id possesses many alleles. The overwritten

letters point out the breed or the strain from which the presence of the single alleles has been

deduced.

3.5. Dermal melanin Cornell

idc ­ Cornell randombred White Leghorn

This mutation differs from the wild id+ because, nevertheless being a Leghorn with genotype

I/I, the pigment is present both in plumage and beak. In this same strain it has been possible

to observe that the females hemizygous for idc and with green legs are meaningfully more

susceptible to the haemangiomas (overgrowth of blood vessels in the skin) in comparison with

their sisters with yellow legs, and therefore hemizygous for Id.

3.6. Dermal melanin Ancona

ida ­ Ancona

This allele obviously allows the deposition of dermal melanin the legs and its existence has

been deduced in the Ancona because of small green spots. Nevertheless the data are not fully

convincing to admit the existence of this new allele, since the phenotype could be explained

through an interference by mo, or with the intervention of modifier genes, or more simply with

the deposit of xanthophyll at epidermal level in narrow areas without uniform distribution,

cause of evident troubles for the breeders of this completely Italian breed.

3.7. Dermal melanin Massachusetts

idM ­ Massachusetts

This mutation appeared in a lineage derived from the crossing between black Langshan and a

commercial meat lineage with dominant white plumage. It differs from the previous alleles

being recognizable only the chicks of a day of life with genotype E, ER, e+, as well as in the

chicks with recessive white. The idM allele provokes the blackest legs when its action is

combined with the gene E. With a genotype c/c_E/- the color of the legs is sometimes diluted,

but it is still intense slate. It is not expressing in the genotypes dominant white, but the

combination I_E gives as result a slate or a pale green color at the age of 10-12 weeks.

3.8. Genetic bases of legs coloration

The phenotypic expression in chickens of the coloration of legs and feet depends on the

interactive and cumulative effects of some greater genes with not identified genes modifiers

able to improve or to reduce the eumelanin.

The effects of the genes id+ and Id are confined to the derma, while the effect of E takes place

above all at epidermal level, but it is also able to add a varying amount of eumelanin to the

derma.

The gene I is epistatic on the epidermal melanin, but at level of the derma it only succeeds in

diluting the pigment, not in eliminating it. Also the recessive white is endowed with a similar

action.

The genes B and mo are the most greater inhibitors of the epidermal melanin of the legs.

Additionally to this, the absence or the presence of the carotenoids (due respectively to W+

and w) interacts with the eumelanin of the derma giving slate blue or green legs.

Despite the numerous studies on the genetics of legs's coloration, they still exist some

variations that have not received an exhaustive explanation.

The genetic deductions have some historical stages consisting firstly in the discovery of the

loci E and Id, with the demonstration that the allele of extension of the black E results in legs

well more black than doesn't happen with the genotype ER. Nevertheless this last gene can be

present in completely black subjects if are joining the necessary intensifier of eumelanin genes

as Ml. This explains why subjects exist with completely black plumage with melanin barely

present or absent in the legs since they have a genotype ER : if the melanin is present, it is

epidermal and it is due to the combined effect of Ml and ER .

Other puzzle is the comparison of a thin green coloration extended to the whole leg or only to

a part, in apparent absence of the gene id+. Other observation: the gene B eliminates the

dermal melanin in the white dominant and white recessive subjects, but it intensifies it in

presence of the gene Co. As last, as already said, the gene Co is able to reduce the intensity of

the yellow legs.

Interactions in which are involved the greater genes of the pigmentation

in determining the coloration of the legs

carotenoids

W+

dermal melanin Id

id+

w

Id

id+

epidermal melanin genotype

phenotype of legs

E

e+

E

e+

E

e+

E

e+

W+W+ IdId EE

W+W+ IdId e+e+

W+W+ id+id+ EE

W+W+ id+id+ e+e+

ww IdId EE

ww IdId e+e+

ww id+id+ EE

ww id+id+ e+e+

almost black legs with white soles

white legs and foot

black legs with black soles

slate legs with white soles

almost black legs with yellow soles

yellow legs and foot

black legs with yellow soles

green legs with yellow soles

3.9. The legs of Pile Modern English Game

Possessing the genetic bases of the coloration of the legs, it is possible to make a practical

digression and to see what it happens when we want to maintain a good pile coloration in the

Modern English Game, whose standard asks for yellow legs.

If the pile is constantly mated with subjects of the same color, it reaches the pure white for the

homozygosis of the dominant white I, then at a certain point we must join a pile with a black

red subject. The black red has olive green legs, and therefore it is homozygous/hemizygous

for id+ according to the sex. Besides, it is homozygous for w, which is not sex-linked.

+

black red male

pile female

w_id+ / w_id+

w_Id/ w_­

+

w_id / w_id = olive green legs

w_Id / w_­ = yellow legs

50% males with yellow legs w_id+/w_Id

50% females with olive legs w_id+/w_­

male gametes

female gametes

w_Id

w_­

w_id+

w_Id/w_id+ w_­/w_id+

w_id+

w_Id/w_id+ w_­/w_id+

pile male

black red female

w_id+ / w_Id

w_id+/ w_­

+

w_id / w_Id = yellow legs

w_id+ / w_­ = olive green legs

25% males with yellow legs w_id+/w_Id

25% males with olive legs w_id+/w_id+

25% females with yellow legs w_Id/w_­

25% females with olive legs w_id+/w_­

male gametes

female gametes

w_id+

w_­

w_id+

w_id+/w_id+ w_­/w_id+

w_Id

w_id+/w_Id w_­/w_Id

From the following square of Punnett it will be evident that to get the 100% of pile

descendants with yellow legs it is worthwhile to join a white rooster homozygous for Id with a

black red female.

white male

black red female

w_Id / w_Id

w_id+/ w_­

w_Id / w_Id = yellow legs

w_id+ / w_­ = olive green legs

female gametes

100% yellow legs w_id+

male gametes

w_­

w_Id w_id+/w_Id w_­/w_Id

w_Id w_id+/w_Id w_­/w_Id

Everything we just exposed refers to the problem of legs. Then, in practice, to get the 100% of

pile subjects it is worthwhile to begin with a white rooster and a black red hen: the descent will

be all pile, being all heterozygous for I, and will have yellow legs.

3.10. Fibromelanosis

Fm ­ fibromelanosis

Autosomal incompletely dominant

Group of association unknown

The characteristic bluish black color of the skin of the Silky is due to dermal eumelanin and

not epidermal, present not only in the immediately underepidermic layer but also in the

deepest derma, the so-called loose connective. The pigment is also well represented in the

parietal and visceral peritoneum, in the periosteum and in the perichondrium. Also the blood

vessels and the nerves don't escape the hyperpigmentation, which winds these structures, and

not even the connective of the entrails is exempt from it.

According to the observations of Stolle, in the first eight days of incubation the number of

melanocytes present in the connective of a Silky and of a partridge Leghorn is roughly

identical, after that in the Silky the amount of melanocytes shows a sudden rise, while in the

Leghorn they die and are phagocytized. The numerical increase occurs even if the skin of the

Silky is put to live in a different environment, as shown by grafts in embryo. Has been Stolle

(1968) to propose the genotype of fibromelanotic subjects, affirming that the phenotype

results from the interaction between id+ and an intensifier endowed with dominance, to which

Hutt had assigned the symbol Fm. According with the data of Stolle, the combination of these

genes gives origin to the following degrees of pigmentation of the connective:

Combination of genes

and intensity of connective pigmentation

locus Fm

locus Id

connective

Fm/Fm/fm+/fm+

fm+/fm+

id+_- or id+/ id+

Id_- or Id/id+_- or id+/ id+

Id_- or Id/-

very dark

few pigment

without pigment

without pigment

In past times other researchers reported about marked variations about the entity of the

fibromelanosis, which suggests the hypothesis that are involved some modifier genes able to

change the phenotypic expression. Some of these genes can be in relationship with those

responsible of the coloration of the plumage, although the Silky is present in the colorations

white, black, blue, pearl grey, buff and wild. Being partial the dominance of Fm, the result of

the crossing of Silky with other breeds must be studied point by point. In a crossing with a

common hen it was gotten, so to say, a melanotic mosaicism: black beak, legs and feet, with

remaining white skin.

3.11. Abdominal pigmented fascia

Abdominal pigmented fascia

Complex interaction between known and unknown genes

incomplete dominance between some genes

The presence of eumelanin in the subcutaneous fascia tightly sticking to the external surface of

the superficial abdominal muscles is not well accepted by the consumer. The pigment can vary

from few spots until the formation of a mantle embracing also the posterior half of the two

muscles, with a color that varies from clear grey to black. It is present in both sexes, even if its

incidence is meaningfully more elevated in females. Jaap (1958) noticed that this anomaly

often joins with the alleles of the locus Id different from id+.

The genetic basis of this eumelanization involves a series of complicated interactions between

known and unknown genes, as well as a relationship of incomplete dominance between some

alleles. The gene I inhibits the pigmentation of the fascia, especially in presence of E, B, and

perhaps also of S. The greater inhibiting effect is determined by the association of I with B,

rather than by these two genes singly taken.

The subjects with genotype E are less pigmented in comparison to those with Columbia

restriction, while the gene B increases the pigmentation in the carriers of Co, especially its allele

Bsd..

The subjects with more elevated pigmentation are those with genotype e+ and eb, and not those

with genotype E. On the contrary the gene eWh is an powerful inhibitor of the pigmentation of

the abdominal fascia.

The recessive white seems able to heighten the abdominal melanin, especially in the chicks

with a smoke colored down. Also the gene id+, according to the observations of Kuit, is able

to determine a marked increase of the melanin of the fascia.

In practice, the data suggest that the most effective genotype in giving the absence of melanin

in the abdominal fascia is the following: I_C+_eWh_B_S_Id.

summary top ahead