caricato da

common.user1940

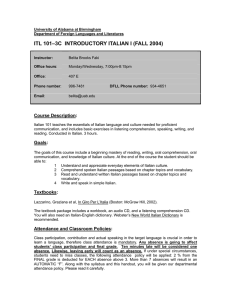

Italian Language Learning: Flashcard Design Guide

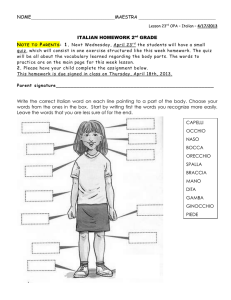

Instructional material design guide Paola Keller s213675 Due Date: 13th December 2010 Instructional material design guide Paola Keller s213675 Teaching material is an important part of most Languages Other Than English (LOTE) programmes. From textbooks, videotapes and Internet resources, teachers rely heavily on a diverse range of material to support their teaching and their student’s learning. However, despite the current rich array of language teaching material commercially available many teachers continue to produce their own material for classroom use. According to Richards, J. (2001) many teachers underestimate how commercial teaching materials are developed and the developmental process that are normally involved. Preparing effective teaching material is similar to the process involved in planning and teaching a lesson. It starts with a learning goal in mind and then seeks to create a set of activities that can enable that goal to be achieved (Richards, 2001). This paper looks at an instructional material produced to teach Italian at the middle school level (Eighth Grade) in a Tasmanian Catholic school. The instructional material designed is a visual aid, consisting of eleven (10) flashcards, created to improve students’ pronunciation and to assess their knowledge on gender and articles in a Language other than English. St. Mary’s College in Hobart At St. Mary’s College, teachers have a syllabus and textbooks they need to follow at a set pace to ensure consistency and to satisfy the requirements of Tasmanian Curriculum framework. The style of presentation, however, is left up to the teacher. They write lesson plans adding their own activities or additional material as they see fit to complement the lesson. The school encourages a personal approach to teaching rather than straight textbook study. Class description The group of students is made up of 30 keen girls who study Italian as a compulsory subject. This is their second year of Italian but based on limited allocated time in the timetable, their level in the target language is at Standard 2, Stage 6, which corresponds to Fourth Grade of the Tasmanian Curriculum (Department of Education, 2009),. Most of the girls are very mature students for their age who are tackling their 2 work with proficiency and eagerness. They are usually full of energy; however, they have a short attention span for anything that they consider boring, useless or too difficult. The students also learn another language; this can become difficult when having to cater for all the diverse language levels in the classroom. Although there is a student in the class where English is not her first language, her proficiency and literacy levels are extremely good for an ESL student. There are times when it becomes difficult for this student when translating pieces of work into English as she does not have all the necessary vocabulary. This is easily overcome with teacher assistance and by the use of created material (textbook or handout) with topic vocabulary at the bottom of the page. There are a couple of students that come from Italian backgrounds and offer a wealth of knowledge on some areas, especially cultural. These students have a very keen approach to their learning and are mature enough to understand the different type of culture and the varying levels of learning in the classroom and accept these differences. According to Piaget (1986-1980), students around the age of 13-14 develop the capacity for abstract, systematic and scientific thinking. For example, adolescents find it easier than children to understand the sorts of higher-order, abstract logic inherent in proverbs, metaphors, and analogies. The adolescent's greater facility with abstract thinking also permits the application of advanced reasoning and logical processes to social and ideological matters. The development of complex thinking leads to dramatic revisions in the way adolescent see themselves, others and the world in general. Their ability to reflect on their own thoughts, combined with the physical and psychological changes they are undergoing, means that they think more about themselves (Inhelder & Piaget, 1955). Piaget's theory assumes that all children go through the same sequence of development, but at different rates. Planning lessons for these different levels of learning is often difficult; the need to be organized is extremely important as some students need extra work and others need more time to work on tasks that have been set. This not only includes their different learning needs but also takes into consideration of their different cultural background. Curriculum connection The aim and the scope of the new instructional material created are to provide all students with knowledge and understanding of the specific vocabulary of items of clothing, the pronunciation, gender and articles in a language other than English. It 3 will also access and integrate knowledge and ideas from Literacy The learning opportunities developed by the material are in line with the requirements of Tasmanian Curriculum at Standard 2, Stage 6: Pronunciation and Intonation: 1. Pronunciation of letter combinations of consonants and vowels e.g. ba, bi, bo, be, bu, da, di, do, de, du Articles: 1. Developing an understanding of gender and forms in definite articles Nouns: 2. Incidental use of gender and number e.g. il papà, la mamma 3. Incidental use of simple plurals e.g. il bambino, i At Standard 2, Stage 6 of the Tasmanian Curriculum Framework for Languages other than English (LOTE), students engage in language tasks that are tightly scaffolded and sequenced and use the language in everyday contexts. They read, view and enjoy a range of familiar, predictable and / or simple texts. Students are developing an understanding of language used in simple, repetitive sentence structures that are heavily dependent on context, visuals, gestures and intonation for understanding. Students recognise and assign meaning to short, familiar texts they see around them, such as classroom signs and labels (Tasmanian Curriculum). Design Guide introduction for a LOTE lesson Learning a foreign language is a cumulative process. Each chapter or lesson is built on all the ones that came before it. The vocabulary and grammatical structure learned in one textbook’s chapter will recur in the next section. Therefore, in order to facilitate and retain students’ previous knowledge, I modified the activity of Unit 7 in the textbook “Pronti Via” on pg 54 and converted the page content into 10 flashcards. The reason for the changes was to create tasks that actively engage students in exposition and assimilation of classroom material. This engagement directly supports my specific learning objective, which is the further introduction of a new grammar structure and facilitate the passage from an activity to the other. As part of such an activity, students would be active – moving, standing, talking and working with props. I believe that the use of flashcards is especially useful for students with visual learning channel or modality preference (Gardener, 1995). Furthermore, an activity with flashcards is valuable for visual, auditory and kinaesthetic learners. In fact, it engages visual learners because they relate to pictures and need the support of 4 diagrams, video or flashcards. It engages auditory learners because they enjoy listening activities and they usually spell a word by sounding it out first. Finally, kinaesthetic learners will enjoy the flashcards game because they may find it hard to sit for long periods of time. In order to introduce the new language grammar I need to reinforce students’ prior knowledge. The flashcards give me the opportunity to assess not only their pronunciation but also their knowledge on articles and gender in the target language. As Piaget (1954) states, students’ or pupils' cognitive ability develops sequentially adapting new experience before modifying schemata to accommodate it. As a teacher, I will affirm, complete or correct a variety of existing schemata. This requires a link between the new learning and prior knowledge. Moreover, the flashcards are a valid material and can be used also as a brainstorming and warm-up activity at the beginning of the next lesson to review previous material. The language context chosen was strictly based on the course book, “Pronti Via”, for Unit 7. All the pictures of the clothing items are represented on pg.54 of the course text. Material designed The material consists of 10 flashcards, designed with Cunnigsworth’s principle (1995) in mind, where activities have to lead to personal involvement and “self-investment” in the learning process, and should include a competitive or problem-solving element. Each card is double sided and shows the word and the article of the item on one side and just the item’s picture in the reverse. Symbols and pictures drawn on the cards facilitate students’ recall. According to O' Neil (1992), picture associations make bridging the gap between the concrete to the symbolic state easy. The idea of double sided flashcards is for different scopes: Flashcards without words Stress the pronunciation and assist in remembering the clothing item's word. The accent on the CDs that accompanied the textbook is Australian/Italian and this has a detrimental effect on the pronunciation. As I am a native speaker, and can model perfect sounding Italian pronunciation, I say the words first and students repeat them. This enables my students to associate my pronunciation with word and image and gives them an authentic experience of the language they are learning. 5 Flashcards with words Review gender and articles. I highlight the masculine and feminine articles, and the endings of the word (noun) with different colours (blue for masculine and pink for feminine). It allows students to easily associate that feminine words in the target language end in "a" and are preceded by the article "la" and masculine words end in "o" and are preceded by the article "il". According to Goldstein (2002), encoding and retrieval are enhanced with the use of colour coding (Goldstein, 2002). Colour coding functions to identify important information, indicate relationships among different pieces of information, organise information, and provide a schema for encoding and retrieving information to and from memory. According to Mastropieri and Scruggs (1991), visual materials help to organise information in a way that enhances encoding and retrieval. The amount of information per card is limited in order to permit students to take a mental “picture” of the information. .. And evaluation: My major aim in producing the flashcards was to transform the book's content into something more appropriate for students’ knowledge and more student-centred. In a Piagetian framework, an acceleration approach may result in superficial and not real learning (Piaget, 1986-1980 It is only when the student has acquired the mental structure to assimilate the new experience that true learning takes place. Moreover, making classes students-centred means thinking about how students are learning and putting them in the role of active participant rather then passive listener (Dewey, 1938-1997). I hope this visual aid will help students master the language forms. I expect also that flashcards produce a few "Aha! moments", derived from the association of the item's article with the item's gender. “Aha! moments" are products of insight teaching, where learning involves a period of mental manipulation of information associated with a problem (Kohler, 1925). The flashcards are stimulating students to notice similarities and differences in the target language patterns. According to the Tasmanian Curriculum, students at Standard 2 are able to implement this mental process. Moreover, Piaget (1886-1980), asserts that in this stage (13-14 years old), intelligence is demonstrated through logical and systematic manipulation of symbols related to concrete objects. 6 Use of the Flashcards in class The flashcards are introduced to students once they have completed the listening and the reading comprehension activity for Unit 7 of the Italian textbook "Pronti Via" (pg.52-53) and they have recorded the new structures and vocabulary on their exercise book. I show the labelled flashcards first and ask to stress and repeat after me the sounds and the pronunciation of the words. Then I present a game with the flashcards without the label: Activity with Flashcards with words: The activity created with the use of the new instructional material should motivate students to improve in the use of three of the four skills, reading, speaking, and listening. According to Wade, Buxton and Kelly (1999), in fact, motivation acts as a drive to perform and to be engaged in a cognitive or physical activity. To comply with the principle of Learning, Teaching and Assessment Principles included in the Tasmanian Curriculum, the flashcards activity is organised reflecting the concepts of Gardner's Multiple Intelligence (1995) and Bloom's Taxonomy (1956). However, it engages students only in lower-order thinking. In fact, the activity explores Level 1 of Boom's Taxonomy in which students do not go beyond simple reproduction of knowledge. Bloom’s taxonomy is a hierarchy of questions which breaks down critical thinking skills into different levels. It is usually depicted as a triangle with six levels (Bloom, 1956). LOTE students need more work at the bottom of the triangle. They need practice asking and answering simple questions first and to understand when and how to use the sentence frames. The flashcards focus just on basic questions such as "Where is…?", where students are asking to simply recall information. In this specific activity much of their work consists of memorization. In general, any information or piece of content that learners or users recollect, identify, and define is at the knowledge level. Activity with Flashcards without words: I invite students to form 5 small circles and I put the set of cards without labels in the centre of each. Then a student asks another, stressing the pronunciation: “Dove e' la giacca?" (Where is the jacket?) The students answer: "La giacca e' qui" (The jacket is here). Then she takes the flashcard with the jacket and gives it to the first student repeating: “Ecco la giacca” (Here is the jacket). She asks her to stick the card on the board. When all the cards are on the board, the group that guesses all the 7 clothing items first, wins. I do not take part in the game but observe the students. As Phye (1997) suggested, observation is the central component of performance assessment. Subsequently, I work with all the class and invite a student to leave the class. Then another student takes a card and hides it. After that, the class asks the student who was out of the room, “Cosa manca?" (What is missing?). The student has to guess it. Comments on activities and material The material is designed, then, not only for challenging students but also to generate participation. In fact, it is designed to allow students to work as a class as well. From this activity I might elicit further information about the students’ understanding of basic grammar structure in the target language. I will decide at the end of the game if it is time to proceed with the next activity or focus more on these grammar concepts. As Vygotzky (1978) states, students are able to do tasks at a higher level if they are given assistance to get them past the zone of proximal development. As a teacher I should provide instruction at a level just above a student's independent level of functioning but not so high that it becomes frustrating for the student. The teaching methodology and learning activity chosen must be those that are appropriate to the cognitive developmental stage of the learner. Moreover, developing new knowledge based on background knowledge (scaffolding) helps to ensure success, motivation and enhance self-esteem (Maslow, 1943). Students gain confidence from practising and repeating familiar language items, and are primed for learning new language later on in the lesson. According to Huitt (2003), the key to learning and remembering new information is repetition. However, in order to be effective this must be done after forgetting begins (Atkinson, R., & Shiffrin, R. 1968). This new instructional material will help students to construct knowledge based on memorization. According to Wright and Haleen (1991), a great variety of language can be conceptualised through the use of these kinds of visual materials. Both the activities with flashcards promote a state of relaxed alertness and a balance of low threat and high challenge which are the ideal elements for higher order functioning and the optimal emotional climate for learning (Caine & Caine, 1994). Most often, students who participate in these innovative instructional approaches 8 perceive a more meaningful learning experience and in some cases actually learn more than students in conventional learning situations (Stage, Muller, Kinzie and Simmons, 1998). Enjoyable activities that require communication between students can foster interaction and friendship in the classroom. Cooperation between students will create a more positive learning environment in which individuals work together to improve their knowledge in the foreign language. Creating a positive learning environment allows the connections to be made within the learners’ brains and, consequently, learning flows (Weare, 2000). According with Maslow (1943), in fact, developing a classroom environment where students are positive and employ cooperative learning methods helps to raise students’ motivation to learn. Employing the Flashcards in learning activity, and engaging students in group activities allows me to stay in line with the requirements of Tasmanian Curriculum framework, which asserts that cooperative learning enables students to gain a much deeper understanding of the different perspectives on contested ideas and issues. In conclusion, this paper presents the modification of instructional materials used to teach Italian as a Language other than English ( LOTE) to a Grade Eight class. I integrated 10 flashcards as a new teaching component to a learning unit of the Italian commercial textbook. The flashcards have been produced in order to help students to review basic Italian grammar concepts and build the necessary knowledge to begin the next textbook activity. They have been developed in accordance with the requirements of Tasmanian Curriculum framework and some of the most important learning theories. References: Atkinson, R., & Shiffrin, R. (1968). Human memory: A proposed system and its control processes. In K Spence & J Spence (Eds.). The psychology of learning and motivation: Advances in research and theory (Vol. 2). New York: Academic Press. Bloom B.S. (1956). Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Co Inc. Caine, R. N., & Caine, G. (1994). Making Connections: Teaching and the HumanBrain. Menlo Park, CA: Addison-Wesley. Cunningsworth, A. (1984) Evaluating and Selecting EFL Teaching Materials. Heinemann. 9 Department of Education Tasmania (2002a). Essential learnings framework 1. Hobart: Author. Dewey, J. (1965). Experience and Education. New York: Collier. Gardner, R.C. (1985). Social Psychology and Language Learning: the Role of Attitudes and Motivation. London: Edward Arnold. Goldstein, E. Bruce. (2002). Sensation andPerception. Pacific Grove, California: Wadsworth. Huitt, W. (2003). A transactional model of the teaching/learning process. Educational Psychology Interactive. Valdosta, GA: Valdosta State University. Kohler, W., (1925). The Mentality of Apes. Norwood, NJ: Ablex. Inhelder, B. & Piaget, J. (1955). De la logique de l’enfant à la logique de l’adolescent. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France. (English version: The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. London: Routledge, 1958) Maslow, A., 1943 A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50, 370-96. Reprinted in P. Harriman (Ed.), Twentieth Century. Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (1991). Teaching students ways to remember. Cambridge: Brookline Books. O'Neil, John (1992). "Wanted: Deep Understanding "Constructivism" Posits New Conception of Learning" Update. 34 Alexandria, VA ASCD (March 92) p5 Piaget, J. (1976). To Understand is to Invent: The Future of Education. New York. Richards, J. C. (2001). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Stage, F., Muller, P., Kinzie, J. and Simmons, A. (1998) ‘Creating Learning Centred Classrooms: What Does Learning Theory Have to Say?, Washington DC, ASHEERIC Higher Education Report Series, Vol 26, No. 4 Phye (1997 Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Wade, S., Buxton, W.M., & Kelly, M. (1999). Using think-alouds to examine readertext interest. Reading Research Quarterly, 34(2), 194-216. Weare, K. (2000). Promoting Mental, Emotional and Social Health – a whole school approach. Ondond: Routledge. 10