PAZIENTE IMMUNOTOLLERANTE E PORTATORE INATTIVO

Dr. Giuliano Alagna

StorianaturaleHBV

Replicazione

viarle

Immunità/risposta

dell’ospite

Liver

Failure

3%

INFEZIONE

ACUTA

INFEZIONE

CRONICA

5%

INACTIVE

CARRIER

Cirrosi

30%

Liver

Cancer

3%

MORTE

ALT

HBVDNA

HBeAg Anatomiapatologica

Immuno-tolerant

Normali

Elevate:>1milioneIU/ml

POS

Minimainfiammazioneofibrosi

HBeAg+

Immuneac:ve

Elevete

Elevate>20,000IU/ml

POS

Infiammazionemoderatasevera

ofibrosi

Inac:veCHB

Normali

Bassoononrilevabile

<2,000IU/ml

NEG

Minimanecroinfiammazionema

fibrosivariabile

HBeAg-immune

reac:va:on

Elevate

Elevate

>2,000IU/ml

NEG

Infiammazionedamoderataa

severaofibrosi

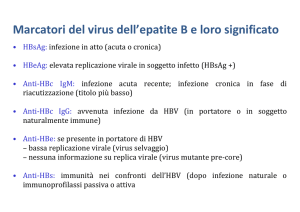

I fase: “immuno tolerant”: HBeAg+, alti livelli di replicazione virale (HBV DNA +++), livelli

normali o bassi di transaminasi lenta progressione della di fibrosi con scarsi segni di

infiammazione/necrosi. Questa fase è più frequente e lunga nei pazienti con infezione

perinatale

o contratta nei primi anni di vita. Basso tasso di perdita dell’ Hbe.

Ifase:“immunotolerant”:HBeAg+,alXlivellidireplicazionevirale(HBV

Fase

altamente contagiosa

DNA+++),livellinormaliobassiditransaminasilentaprogressionedella

difibrosiconscarsisegnidiinfiammazione/necrosi.Questafaseèpiù

IIfrequenteelunganeipazienXconinfezioneperinataleocontrabanei

fase: “immuno reactive phase”: HbeAg+, bassa replica virale con basso HBV DNA,

livelli aumentati o fluttuanti di transaminasi, segni di moderata o severa necrosi ed

primiannidivita.Bassotassodiperditadell’HBe.Fasealtamente

infiammazione

epatica e più rapida progressione verso la fibrosi rispetto alla fase I.

Piutipica

dell’ età adulta

contagiosa

III fase: “inactive HBV carrier state”: può seguire la sieroconversione da HBeAg+ ad

HbeAg negativo. E' caratterizzata da bassissimi valori di HBV DNA e livelli normali di

aminotransferasi. Questo stadio è associato ad una bassa probabilità di progressione

verso

la cirrosi e l'HCC….

IIIfase:“inacXveHBVcarrierstate”:puòseguirelasieroconversioneda

HBeAg+adanXHBeAg.E'caraberizzatadabassissimivaloridiHBVDNA

IV fase: “HBeAg-negative CHB” .: E' caratterizzata da periodiche riattivazioni con

elivellinormalidiaminotransferasi.E’necessariounfollowupminimo

fluttuazioni

sia dell'HBV DNA che delle transaminasi.

diunannomonitorizzandoleALT(<40UI/ML)el’HBVDNA(<2000U/

Vml).Questostadioèassociatoadunabassaprobabilitàdiprogressione

fase: “HBsAg negative phase” dopo la perdita dell'antigene di superficie bassi valori di

HBV

DNA possono persistere. La perdita dell' HBsAg è associata ad un miglioramento

versolacirrosiel'HCC

dell' outcome con una riduzione del rischio di progressione verso la cirrosi e verso l'HCC.

IN QUESTI PAZIENTI L'IMMUNOSOPPRESSIONE PUO' PORTARE ALLA RIATTIVAZIONE DELL'HBV

HBV carriers (HBsAg+):

attivo HBeAg o anti HBe+ HBV DNA>20000 UI/ml

inattivo HBeAg – Anti HBe+HBV DNA<2000 UI/ml

Occult HBV carriers (HBsAg-):

HBV DNA rilevabile come CCC DNA o HBV

DNA nel siero molto basso

IMMUNOTOLLERANTE

need for treatment. Of note, some persons will be in the

“gray zones,” meaning that their HBV DNA and ALT

evels do not fall into the same phase. Longitudinal

ollow-up of ALT and HBV DNA levels and/or assessment of liver histology can serve to clarify the phase of

nfection.

i. Immune-tolerant phase: In this highly replicative/

low inflammatory phase, HBV DNA levels are

elevated, ALT levels are normal (<19 U/L for

females and <30 U/L for males), and biopsies

are without signs of significant inflammation or

fibrosis. The duration of this phase is highly variable, but longest in those who are infected perinatally. With increasing age, there is an

increased likelihood of transitioning from

immune-tolerant to the HBeAg-positive immuneactive phase.

ii. HBeAg-positive immune-active phase: Elevated

ALT and HBV DNA levels in conjunction with

liver injury characterize this phase. Median age of

onset is 30 years among those infected at a young

age. The hallmark of transition from the HBeAgpositive immune-active to -inactive phases is

HBeAg seroconversion. The rate of spontaneous

Ø HBVDNAelevato

Ø ALTnormali(F<19UI/ml;

M<30UI/ml)

Ø Nofibrosi

Ø Fasepiùfrequentenelleprime

duedecadi

Guarigione

Formacronica

90-95%

5-10%

Bambinie

AdolescenX

40%

60%

NeonaX

10%

90%

AdulX

PerinatalvspostnatalacquisiXon(1)

Journal of Hepatology 48 (2008) 335–352

www.elsevier.com/locate/jhep

Review

Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: Special emphasis

on disease progression and prognostic factorsq

1,*

2

Giovanna Fattovich , Flavia Bortolotti , Francesco Donato

1

3

Department of Surgical and Gastroenterological Sciences, University of Verona, Piazzale L.A. Scuro, 10, Verona 37134, Italy

2

Fifth Medical Clinic, University of Padova, Padova, Italy

3

Institute of Hygiene, Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy

The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and disease is complex and highly variable. We review

the natural history of chronic hepatitis B with emphasis on the rates of disease progression and factors influencing the

course of the liver disease. Chronic hepatitis B is characterized by an early replicative phase (HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis) and a late low or non-replication phase with HBeAg seroconversion and liver disease remission (inactive carrier

state). Most patients become inactive carriers after spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion with good prognosis, but progression to HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis due to HBV variants not expressing HBeAg occurs at a rate of 1–3 per 100 person years following HBeAg seroconversion. The incidence of cirrhosis appears to be about 2-fold higher in HBeAg negative

compared to HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis. In the cirrhotic patient the 5-year cumulative risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma is 17% in East Asia and 10% in the Western Europe and the United States and the 5-year liver related

death rate is 15% in Europe and 14% in East Asia. There is a growing understanding of viral, host and environmental

factors influencing disease progression, which ultimately could improve the management of chronic hepatitis B.

! 2007 European Association for the Study of the Liver. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis B; Natural history; Prognostic factors

1. Introduction

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) currently affects about 400 million people, particularly in

developing countries, and it is estimated that worldwide

over 200,000 and 300,000 chronic HBV carriers die each

year from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma

(HCC), respectively [1,2]. The natural history of chronic

HBV infection and disease is variable and complex and

has still not been completely defined. A careful understanding of the clinical outcomes and factors affecting

Associate Editor: R.P. Perrillo

q

The authors declare that they do not have anything to disclose

regarding funding from industries or conflict of interest with respect to

this manuscript

*

Corresponding author. Tel./fax: +39 045 8124205.

E-mail address: [email protected] (G. Fattovich).

Perinatale

Ø InasiaibambiniinfebaXinepocaperinatale,presentanonormalivaloridiALT

conminimodannoepaXco(immunotolerantphase),essendoperaltro

asintomaXci

disease progression is important in the management of

chronic hepatitis B. This article reviews the natural history of chronic hepatitis B, with emphasis on summarizing the available data to estimate the rates of disease

progression according to the stage of the disease and

factors influencing its course.

2. Phases of chronic HBV infection

The likelihood of developing chronic HBV infection is

higher in individuals infected perinatally (90%) or during

childhood (20–30%), when the immune system is thought

to be immature, compared with immunocompetent subjects infected during adulthood (<1%). The phases of

chronic HBV infection described herein refer to patients

infected early in life. The natural course of chronic HBV

infection can be divided into four phases based on the

0168-8278/$32.00 ! 2007 European Association for the Study of the Liver. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011

Ø LapercentualedisieroconversioneadanXHBeèmoltovariabileaseconda

deglistudi(1,2)essendocompresatrail10edil75%a10/13annid’età

Ø QuandosihalasieroconversionedaHBeadanXHBe,siassisteall’incremento

delleALTedallariduzionedell’HBVDNA(puntonodale)

Ø Studilongitudinalidocumentanochelasieroconversioneconduceallostadio

diportatoreinamvo(clearancedell’HBsAg0.6%/anno);neibambiniincuisiha

unaseveranecroinfiammazionedurantelasieroconversioneanXHBesipuò

avereunarapidaprogressioneversolacirrosielosviluppodiHCC

1ChuCM,LiawYF.ChronichepaXXsBvirusinfecXonacquiredinchildhood:specialemphasisonprognosXcandtherapeuXcimplicaXonof

delayedHBeAgseroconversion.JViralHepat2007;14:147–152.

2MarxG,MarXnSR,ChicoineJF,AlvarezF.Long-termfollow-upofchronichepaXXsBvirusinfecXoninchildrenofdifferentethnicorigin.J

InfectDis2002;186:295–301.

Journal of Hepatology 48 (2008) 335–352

www.elsevier.com/locate/jhep

Review

Natural history of chronic hepatitis B: Special emphasis

on disease progression and prognostic factorsq

PerinatalvspostnatalacquisiXon(2)

Giovanna Fattovich1,*, Flavia Bortolotti2, Francesco Donato3

1

Department of Surgical and Gastroenterological Sciences, University of Verona, Piazzale L.A. Scuro, 10, Verona 37134, Italy

2

Fifth Medical Clinic, University of Padova, Padova, Italy

3

Institute of Hygiene, Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy

The natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and disease is complex and highly variable. We review

the natural history of chronic hepatitis B with emphasis on the rates of disease progression and factors influencing the

course of the liver disease. Chronic hepatitis B is characterized by an early replicative phase (HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis) and a late low or non-replication phase with HBeAg seroconversion and liver disease remission (inactive carrier

state). Most patients become inactive carriers after spontaneous HBeAg seroconversion with good prognosis, but progression to HBeAg negative chronic hepatitis due to HBV variants not expressing HBeAg occurs at a rate of 1–3 per 100 person years following HBeAg seroconversion. The incidence of cirrhosis appears to be about 2-fold higher in HBeAg negative

compared to HBeAg positive chronic hepatitis. In the cirrhotic patient the 5-year cumulative risk of developing hepatocellular carcinoma is 17% in East Asia and 10% in the Western Europe and the United States and the 5-year liver related

death rate is 15% in Europe and 14% in East Asia. There is a growing understanding of viral, host and environmental

factors influencing disease progression, which ultimately could improve the management of chronic hepatitis B.

! 2007 European Association for the Study of the Liver. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis B; Natural history; Prognostic factors

1. Introduction

Chronic infection with hepatitis B virus (HBV) currently affects about 400 million people, particularly in

developing countries, and it is estimated that worldwide

over 200,000 and 300,000 chronic HBV carriers die each

year from cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma

(HCC), respectively [1,2]. The natural history of chronic

HBV infection and disease is variable and complex and

has still not been completely defined. A careful understanding of the clinical outcomes and factors affecting

Associate Editor: R.P. Perrillo

q

The authors declare that they do not have anything to disclose

regarding funding from industries or conflict of interest with respect to

this manuscript

*

Corresponding author. Tel./fax: +39 045 8124205.

E-mail address: [email protected] (G. Fattovich).

Postnatal

disease progression is important in the management of

chronic hepatitis B. This article reviews the natural history of chronic hepatitis B, with emphasis on summarizing the available data to estimate the rates of disease

progression according to the stage of the disease and

factors influencing its course.

Ø Lamaggiorpartedeibambiniconinfezioneacquisitaarrivaall’osservazionein

unafasediincrementodelleALTconmalamaamva

2. Phases of chronic HBV infection

The likelihood of developing chronic HBV infection is

higher in individuals infected perinatally (90%) or during

childhood (20–30%), when the immune system is thought

to be immature, compared with immunocompetent subjects infected during adulthood (<1%). The phases of

chronic HBV infection described herein refer to patients

infected early in life. The natural course of chronic HBV

infection can be divided into four phases based on the

0168-8278/$32.00 ! 2007 European Association for the Study of the Liver. Published by Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2007.11.011

Ø SieroconversioneadanXHBetrail14-16%/annoduranteiprimi10anni

Ø InunostudiolongitudinaleItaliano(*)il95%dibambiniandaXincontroa

sieroconversioneHBesonodiventaXportatoriinamviprimadelraggiungimento

dell’etàadulta

*BortolomF,GuidoM,BartolacciS,CadrobbiP,CrivellaroC,NoventaF,etal.ChronichepaXXsBinchildrenavereanXgen

seroclearance:finalreportofa29yearlongitudinalstudy.Hepatology2006;43:556–562.

Table 2. Among 17 studies of inter

47

Ageand

overRationale

40 years is associa

years.

Evidence

tolerant

adults,

only

two examined

Recommendations

Quality/Certainly

of

Evidence:

Moderate

The

evidence

profile

is summ

lihood

of

significant

histological

Technical Remark

than

ULNs,

whereas

most

used

AL

Strength of Recommendation: Strong

Table

2.

Among

17

studies

of

inte

positivefor

persons

with All

normal

ALT

The AASLD status

recommends

against

inclusion.

were

RCTsle

1.2A.Immune-tolerant

should be

definedantiviral

by ALT ULNs

tolerant adults,

only two

examined

Technical

Remark

thanofULNs,

whereas

24-48 weeks

formost

IFN orused

48 wA

therapy

adults with

CHB.!19 U/L tion

levelsforutilizing

!30immune-tolerant

U/L for men and

ULNs

forand

inclusion.

All werefollow

RCT

1. Immune-tolerant

status

should

defined

by ALT Evidence

12

months

of Rationale

post-treatment

for women as ULNs

rather

thanbe local

laboratory

of 24-48 weeks for IFN or 48

Quality/Certainly

Evidence:

Moderate

levels utilizing of

!30

U/L for

men and !19 U/L tion

The

evidence

profile is summa

HBeAg

loss and

seroconversion

as t

ULNs.

12

months

of

post-treatment

follo

for

women

as

ULNs

rather

than

local

laboratory

Strength of Recommendation: Strong

Table

2. Among

interv

whereas

onlyand

two17seroconversion

studies ofevaluate

HBeAg

loss

as

ULNs.

2B. The AASLD suggests that ALT levels be tested tolerant

whereascomparing

only only

twoantiviral

studies

evaluat

studies

therapy

adults,

two

examined

2B.

The

AASLD

suggests

that

ALT

levels

be

tested

at least Remark

every 6 months for adults with immune- ment

studies comparing antiviral therap

Technical

were thewhereas

primarymost

studies

ULNs,

usedinform

AL

at least every 6 months for adults with immune- than

ment

were

the

primary

studies

info

tolerant

CHB

to

monitor

for

potential

transition

to

CHB to monitor for potential transition to ULNs

dation.

The

remaining

1212RCTs

studies

for

inclusion.

All

were

dation.

The

remaining

studi

1.tolerant

Immune-tolerant

status

should

be

defined

by

ALT

immune-active

or

-inactive

CHB.

immune-active or -inactive CHB.

comparisons

antiviral

comparisons

ofdifferent

different

antiviral

tion

of 24-48 ofweeks

for IFN

or 48the

wth

levels

utilizing

!30

U/L

for

men

and

!19

U/L

Comparedtotountreated/placebo

untreated/placebo

Quality/Certainly

Very low

low

Compared

Quality/Certainly of

of Evidence:

Evidence: Very

12

months

of

post-treatment

follow

for women

as ULNs rather than

local laboratory ralral therapy

therapy resulted in a signifi

Strength

of Recommendation:

Conditional

resulted

in a95%

significa

Strength of Recommendation: Conditional

HBeAg

loss

(RR,

2.69;

HBeAg

loss

and

seroconversion

asCI:th

ULNs.

2C.

The AASLD suggests antiviral therapy in the HBeAg

loss (RR,

(RR, 2.22;

2.69;95%

95%CI:

CI:11

conversion

onlyby(RR,

two

studies

evaluate

2C.group

The AASLD

antiviral

in the whereas

select

of adultssuggests

>40 years

of agetherapy

with normal

of

results

treatment

type

conversion

2.22;

95%

CI:(IFN

1.2

2B.

The

AASLD

suggests

that

ALT

levels

be

tested

ALT

and

elevated

HBV

DNA

("1,000,000

IU/mL)

select group of adults >40 years of age with normal studies

comparing

therapy

dine)

yielded

RR antiviral

that type

included

of

results

by

treatment

(IFN1a

and

liver

biopsy

showing

significant

necroinflammaatALT

leastandevery

6

months

for

adults

with

immuneferentwere

from

controls).

T

elevated HBV DNA ("1,000,000 IU/mL) ment

theuntreated

primary

studies

inform

tion or fibrosis.

dine)

yielded

RR

that

included

1

(

low-to-moderate

quality

and

the

tolerant

CHB

to

monitor

for

potential

transition

to

and liver biopsy showing significant necroinflamma- dation.

Thebaseline

remaining

12

studies

ferent

from

untreated

Th

sons with

ALTcontrols).

values

less

Quality/Certainly of Evidence: Very low

immune-active

or -inactive CHB.

tion

or fibrosis.

low to low quality.

comparisons

of different

Strength

of Recommendation: Conditional

low-to-moderate

qualityantiviral

and thetheR

There are no studies demons

Compared

to untreated/placebo

sons

with baseline

ALT values less t

Quality/Certainly

of

Evidence:

Very

low

Quality/Certainly

of

Evidence:

Very

low

therapy is beneficial in reducing ra

Technical Remark

toliver-related

low quality.

rallow

resulted

in ina persons

significa

StrengthofofRecommendation:

Recommendation:Conditional

Conditional

Strength

andtherapy

death

1. Moderate-to-severe necroinflammation or fibrosis

CHB.

Finite

duration

Thereloss

are(RR,

notreatment

studies95%

demonst

HBeAg

2.69;

CI: 1

therapy for adults with immune-tolerant CHB.

INACTIVECARRIER

q Qualisonoicriterioggemviperindividuarlo?

q Qualeèilrischiodiprogressionedimalamae

sviluppoHCC?

q Rischiodiriamvazione

q QualeXpodifollowupbisognaapplicareinquesX

pazienX?

Ø L’interazionetravirusedimmunitàdell’ospitespiegaladinamicitàdelle

fasidimalama

Ø Lacompressionedellasuddebadinamicitàdellastorianaturalehaindobo

adunavariazionedellaterminologiauXlizzata

1960

Healtycarrier

AsyntomaXcHBsAgcarrier

InacXveHBsAgcarrier

InacXvecarrierstate

2016

LowreplicaXvechronicHBVInfecXon(APASL)

Qualisonoicriterioggemviperindividuarlo?

ü ALT

ü LivelliHBVDNA

ü IstologiaepaXca?

ü ALT

Clinical Practice Guidelines

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of chronic

hepatitis B virus infection

European Association for the Study of the Liver⇑

Introduction

Our understanding of the natural history of hepatitis B virus

(HBV) infection and the potential for therapy of the resultant disease is continuously improving. New data have become available

since the previous EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) prepared in 2008 and published in early 2009 [1]. The objective of

this manuscript is to update the recommendations for the optimal management of chronic HBV infection. The CPGs do not fully

address prevention including vaccination. In addition, despite the

increasing knowledge, areas of uncertainty still exist and therefore clinicians, patients, and public health authorities must continue to make choices on the basis of the evolving evidence.

been increasing over the last decade as a result of aging of the

HBV-infected population and predominance of specific HBV

genotypes and represents the majority of cases in many areas,

including Europe [4,9,10]. Morbidity and mortality in CHB are

linked to persistence of viral replication and evolution to cirrhosis

and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Longitudinal studies of

untreated patients with CHB indicate that, after diagnosis, the

5-year cumulative incidence of developing cirrhosis ranges

from 8% to 20%. The 5-year cumulative incidence of hepatic

decompensation is approximately 20% for untreated patients

with compensated cirrhosis [2–4,11–13]. Untreated patients with

decompensated cirrhosis have a poor prognosis with a 14–35%

probability of survival at 5 years [2–4,12]. The worldwide incidence of HCC has increased, mostly due to persistent HBV and/

or HCV infections; presently it constitutes the fifth most common

cancer, representing around 5% of all cancers. The annual incidence of HBV-related HCC in patients with CHB is high, ranging

from 2% to 5% when cirrhosis is established [13]. However, the

incidence of HBV related HCC appears to vary geographically

and correlates with the underlying stage of liver disease and possibly exposure to environmental carcinogens such as aflatoxin.

Population movements and migration are currently changing

the prevalence and incidence of the disease in several low endemic countries in Europe and elsewhere. Substantial healthcare

resources will be required for control of the worldwide burden

of disease.

Aminimumfollow-upof1yearwithalanineaminotransferase(ALT)levelsatleast

every3–4monthsandserumHBVDNAlevelsisrequiredbeforeclassifyingapaXent

asinacXveHBVcarrier.ALTlevelsshouldremainpersistentlywithinthenor-mal

Context

rangeaccordingtotradiXonalcut-offvalues(approximately40IU/ml)

Epidemiology and public health burden

Approximately one third of the world’s population has serological

evidence of past or present infection with HBV and 350–400 million people are chronic HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) carriers. The

spectrum of disease and natural history of chronic HBV infection

are diverse and variable, ranging from an inactive carrier state to

progressive chronic hepatitis B (CHB), which may evolve to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [2–4]. HBV-related

end stage liver disease or HCC are responsible for over 0.5–1 million deaths per year and currently represent 5–10% of cases of

Natural history

ü ALT

Digestive and Liver Disease 43S (2011) S8–S14

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Digestive and Liver Disease

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dld

Ø on

MolXdeglistudicondomperindividuare

Natural history of chronic HBV infection: special emphasis

the

prognostic implications of the inactive carrier state versus chroniceventualirischilegaXallostatodiportatore

hepatitis

inamvosonostaXviziaXdalfabocheèstata

a, 1

b,1

a

b

Erica Villa *, Giovanna Fattovich , Antonella Mauro , Michela Pasino considerataun’unicamisurazionedelleALT

a Gastroenterology and Liver Clinic, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy

b Gastroenterology Clinic, Department of Medicine, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

Abstract

Ø Glistudicondomconabentomonitoraggiodelle

ALThannoevidenziatocomepiùdell’85%dei

pazienXritenuXcarrier,loeranoeffemvamente

inaccordoconl’esameistologico

The evaluation of the natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection requires the precise definition of the various clinical

conditions that can be encountered (i.e. inactive carrier state or subject with liver disease activity). This can be achieved by repeat monitoring

of ALT, serum HBV-DNA levels (over a period of at least 1 year, according to international guidelines) and/or evaluation of HBsAg titre.

Liver biopsy may offer additional information although it is not mandatory.

Overall, the natural history of the true inactive carrier is benign: reactivation of hepatitis, especially in Western countries, is rare and is

usually due to co-factors (like alcohol or drugs); spontaneous HBsAg loss is frequent (around 1% per year) and HCC development rare. On

the other hand, in patients with chronic hepatitis B or cirrhosis, the risk of reactivation, of HCC development and of liver-related mortality is

much higher, especially in Eastern countries, and should therefore lead to antiviral therapy.

© 2010 Editrice Gastroenterologica Italiana S.r.l. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis; Hepatitis B virus; Inactive carrier state; Prognosis

During the last few years there has been a substantial mod-

carrier”. Although several studies on the natural history of

implications. Indeed, several conditions have to be fulfilled for

of an “inactive carrier state” rather than an “inactive carrier”,

NaturalhistoryofchronicHBVcarriersinNorthernItaly:morbidityandmortalityaver30years.MannoM,Camma`C,SchepisF,etal.

ification of the nomenclature regarding Hepatitis B surface patients with chronic HBV infection have been published,

Gastroenterology2004;127:756−63.

Antigen (HBsAg) carriers with no or scarce evidence of active a comprehensive analysis is hampered by the different

DeFranchisR,MeucciG,VecchiM,etal.ThenaturalhistoryofasymptomaXchepaXXsBsurfaceanXgencarriers.AnnInternMed1993

liver disease. The definition of “healthy carrier” used in the study designs (case–control, cross-sectional, longitudinal) and

1960s has been changed to “asymptomatic HBsAg carrier”, the heterogeneity of the patient populations relative to the

VilleneuveJP,DesrochersM,Infante-RivardC,etal.Along-termfollow-upstudyofasymptomaXchepaXXsBsurfaceanXgen-posiXvecarriersin

and recently this has been further modified to “inactive clinical setting (inactive carrier, asymptomatic carrier, chronic

Montreal.Gastroenterology1994

HBsAg carrier”. This progressive modification is more than hepatitis). Available data have called into question the concept

a mere semantic process, as it has substantial clinical of inactive carrier, and proposals have been made to speak

Long-termoutcomeofhepaXXsBeanXgen-negaXvehepaXXsB

surfaceanXgencarriersinrelaXontochangesofalanine

aminotransferaselevelsoverXme

4376HBsAg+,HBeAg-“carrier”

ALTvalutateogni3mesi/annoper3anni

1720pazienX(46.8%)neisuccessivitrediciannihannoavutounincrementodelle

transaminasi

Transaminasipersistentementenormalicorrelanoconun’eccellenteprognosi

Unincremento2ULNduranteilFUèassociatoadun’aumentatamorbiditàemortalità

Unincremento2ULNpuòessereconsideratoilcut-offdecisionaleriguardolaterapia

TaiDietal.Hepatology.2009Jun;49(6):1859-67

ü ALT

Clinical Practice Guidelines

EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: Management of chronic

hepatitis B virus infection

European Association for the Study of the Liver⇑

Introduction

Our understanding of the natural history of hepatitis B virus

(HBV) infection and the potential for therapy of the resultant disease is continuously improving. New data have become available

since the previous EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) prepared in 2008 and published in early 2009 [1]. The objective of

this manuscript is to update the recommendations for the optimal management of chronic HBV infection. The CPGs do not fully

address prevention including vaccination. In addition, despite the

increasing knowledge, areas of uncertainty still exist and therefore clinicians, patients, and public health authorities must continue to make choices on the basis of the evolving evidence.

been increasing over the last decade as a result of aging of the

HBV-infected population and predominance of specific HBV

genotypes and represents the majority of cases in many areas,

including Europe [4,9,10]. Morbidity and mortality in CHB are

linked to persistence of viral replication and evolution to cirrhosis

and/or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Longitudinal studies of

untreated patients with CHB indicate that, after diagnosis, the

5-year cumulative incidence of developing cirrhosis ranges

from 8% to 20%. The 5-year cumulative incidence of hepatic

decompensation is approximately 20% for untreated patients

with compensated cirrhosis [2–4,11–13]. Untreated patients with

decompensated cirrhosis have a poor prognosis with a 14–35%

probability of survival at 5 years [2–4,12]. The worldwide incidence of HCC has increased, mostly due to persistent HBV and/

or HCV infections; presently it constitutes the fifth most common

cancer, representing around 5% of all cancers. The annual incidence of HBV-related HCC in patients with CHB is high, ranging

from 2% to 5% when cirrhosis is established [13]. However, the

incidence of HBV related HCC appears to vary geographically

and correlates with the underlying stage of liver disease and possibly exposure to environmental carcinogens such as aflatoxin.

Population movements and migration are currently changing

the prevalence and incidence of the disease in several low endemic countries in Europe and elsewhere. Substantial healthcare

resources will be required for control of the worldwide burden

of disease.

Aminimumfollow-upof1yearwithalanineaminotransferase(ALT)levels

atleastevery3–4monthsandserumHBVDNAlevelsisrequiredbefore

classifyingapa:entasinac:veHBVcarrier.

Context

Epidemiology and public health burden

Approximately one third of the world’s population has serological

evidence of past or present infection with HBV and 350–400 million people are chronic HBV surface antigen (HBsAg) carriers. The

spectrum of disease and natural history of chronic HBV infection

are diverse and variable, ranging from an inactive carrier state to

progressive chronic hepatitis B (CHB), which may evolve to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [2–4]. HBV-related

end stage liver disease or HCC are responsible for over 0.5–1 million deaths per year and currently represent 5–10% of cases of

liver transplantation [5–8]. Host and viral factors, as well as coinfection with other viruses, in particular hepatitis C virus (HCV),

hepatitis D virus (HDV), or human immunodeficiency virus

BruneboMR,Hepatology1989;CPG,EASL2012

(HIV) together with other co-morbidities including alcohol abuse

Liuj1Hepatology.2016

and obesity, can affect the natural course of HBV infection as well

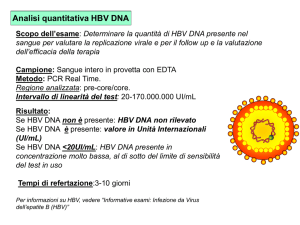

Ø HBVDNA<2000UI/mL

Ø HBsAg<1000UI/mL

Natural history

ü HBVDNA

Chronic HBV infection is a dynamic process. The natural history

of chronic HBV infection can be schematically divided into five

phases, which are not necessarily sequential.

Digestive and Liver Disease 43S (2011) S8–S14

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Digestive and Liver Disease

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dld

ü ISTOLOGIA

Natural history of chronic HBV infection: special emphasis on the

prognostic implications of the inactive carrier state versus chronic hepatitis

Erica Villaa, 1*, Giovanna Fattovichb,1, Antonella Mauroa , Michela Pasinob

a Gastroenterology and Liver Clinic, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy

b Gastroenterology Clinic, Department of Medicine, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

Abstract

The evaluation of the natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection requires the precise definition of the various clinical

conditions that can be encountered (i.e. inactive carrier state or subject with liver disease activity). This can be achieved by repeat monitoring

of ALT, serum HBV-DNA levels (over a period of at least 1 year, according to international guidelines) and/or evaluation of HBsAg titre.

Liver biopsy may offer additional information although it is not mandatory.

Overall, the natural history of the true inactive carrier is benign: reactivation of hepatitis, especially in Western countries, is rare and is

usually due to co-factors (like alcohol or drugs); spontaneous HBsAg loss is frequent (around 1% per year) and HCC development rare. On

the other hand, in patients with chronic hepatitis B or cirrhosis, the risk of reactivation, of HCC development and of liver-related mortality is

much higher, especially in Eastern countries, and should therefore lead to antiviral therapy.

© 2010 Editrice Gastroenterologica Italiana S.r.l. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Ø Pochistudi*hannoriportatodaXriguardol’istologianeiportatoriinamvi;

difabosoloil3%presenterebbeun’epaXtecronicamoderata

Keywords: Chronic hepatitis; Hepatitis B virus; Inactive carrier state; Prognosis

During the last few years there has been a substantial modification of the nomenclature regarding Hepatitis B surface

Antigen (HBsAg) carriers with no or scarce evidence of active

liver disease. The definition of “healthy carrier” used in the

1960s has been changed to “asymptomatic HBsAg carrier”,

and recently this has been further modified to “inactive

HBsAg carrier”. This progressive modification is more than

a mere semantic process, as it has substantial clinical

implications. Indeed, several conditions have to be fulfilled for

a subject to be included in this subgroup of inactive hepatitis B

virus (HBV) carriers, namely: hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)

negative, antibody to HBeAg (anti-HBe) positive, persistently

normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels, serum HBV-DNA<2000IU/ml,

and, whenever available, liver histology with low grade

inflammation (less than 4) [1].

The evidence, however, for these stringent criteria is

supported by limited data as there are only few longitudinal

cohort studies with a clear-cut definition of “inactive HBsAg

*Corresponding author. Prof. Erica Villa. Gastroenterology and Liver

Clinic, Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria, University of Modena and Reggio

Emilia, Modena, Via del Pozzo 71, 41124 Italy.

Tel.: +390594225308; fax: +390594224363.

E-mail address: [email protected] (E. Villa).

1

carrier”. Although several studies on the natural history of

patients with chronic HBV infection have been published,

a comprehensive analysis is hampered by the different

study designs (case–control, cross-sectional, longitudinal) and

the heterogeneity of the patient populations relative to the

clinical setting (inactive carrier, asymptomatic carrier, chronic

hepatitis). Available data have called into question the concept

of inactive carrier, and proposals have been made to speak

of an “inactive carrier state” rather than an “inactive carrier”,

implying a possible reversion of the condition [2]. A careful

understanding of the clinical features and outcome of the

inactive HBsAg carrier is relevant for the management of

chronic HBV infection. For this purpose this article will

review the literature regarding liver function, viral replication,

liver histology and clinical course in an attempt to better

define the features of the inactive HBsAg carrier state and to

evaluate differences in prognosis according to clinical settings

(inactive carrier state or chronic hepatitis).

1. Liver function

Ø L’associazionedelsolodosaggiodelletransaminasiedell’HBVDNApuò

portareadunaperditadicircail10%dimalameepaXcheistologicamente

significaXve

A major bias influencing the results of studies on patients

with chronic HBV infection is the cross-sectional, instead

These authors contributed equally.

© 2010 Editrice Gastroenterologica Italiana S.r.l. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

DeFranchisR,MeucciG,VecchiM,etal.ThenaturalhistoryofasymptomaXchepaXXsBsurfaceanXgencarriers.AnnInternMed

1993;118:191−4.

VelascoM,González-CerónM,delaFuenteC,etal.ClinicalandpathologicalstudyofasymptomaXcHBsAgcarriersinChile.Gut1978

MarXnot-PeignouxM,BoyerN,ColombatM,etal.SerumhepaXXsBvirusDNAlevelsandliverhistologyininacXveHBsAgcarriers.JHepatol

2002;36:543−6.

Liver International ISSN 1478-3223

REVIEW ARTICLE

The prognosis and management of inactive HBV carriers

! 2, Glenda Grossi1 and Pietro Lampertico1

Federica Invernizzi1, Mauro Vigano

1 ‘A. M. and A. Migliavacca’ Center for Liver Disease, Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology Fondazione IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale

Maggiore Policlinico, Universit!

a di Milano, Milano, Italy

2 Hepatology Unit, Ospedale San Giuseppe, Universit!

a degli Studi di Milano, Milano, Italy

DOI: 10.1111/liv.13006

Abstract

Patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection lacking the serum hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) and with antibodies

against HBeAg (anti-HBe), are the prevalent subgroup of HBV carriers worldwide. The prognosis of these patients is different

Ø UXlizzodellatransientelastography(TE)perdiscriminareICdaHBsAgnegaXveCHB

from inactive carriers (ICs), who are characterized by persistently normal serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and low

(<2000 IU/ml) serum HBV DNA levels, a serological profile that may also be intermittently observed in patients with HBeAgnegative chronic hepatitis. This is why a confirmed diagnosis of IC requires quarterly ALT and HBV DNA measurements for at

least 1 year, while a single-point detection of combined HBsAg <1000 IU/ml and HBV DNA <2000 IU/ml has a robust predictive value for the diagnosis of IC. Characteristically, ICs have minimal or no histological lesions of the liver corresponding to

liver stiffness values on Fibroscan of <5 kPa. Antiviral treatment is not indicated in ICs since the prognosis for the progression

of liver disease is favourable if there are no cofactors of liver damage such as alcohol abuse, excess weight or co-infection with

the hepatitis C virus or delta virus. Moreover, spontaneous HBsAg loss frequently occurs (1–1.9% per year) in these patients

while the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is rare, at least in Caucasian patients. However, an emerging issue

reinforcing the need for clinical surveillance of ICs is the risk of HBV reactivation in patients who undergo immunosuppressive

therapy without receiving appropriate antiviral prophylaxis. After diagnosis, management of ICs includes monitoring of ALT

and HBV DNA every 12 months with periodic measurement of serum HBsAg levels to identify viral clearance.

Ø NegliIcslasXffnessmediacalcolataneglistudièdi5KPa(limitesuperioredi7.9Kpa)

Ø L’evidenzadipiùelevaXdisXffnessinpazienteconsoppressioneviraleenormaliAlt

puòindicareundannoepaXcosecondarioadaltracausa,suggerendounpiùabento

monitoraggiool’esecuzionediunabiopsiaepaXca

Keywords

antiviral treatment – HCC – hepatitis B virus – inactive carriers – natural history – prophylaxis

Olivieri

from patients with HBeAg-negative

2008 4.3+/-1KPa

hepatitis because of the different

Maimone

2009 4.83+/-1KPa

Castera

2011 4.8+/-2KPa

An estimated 340 million individuals are chronically

infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) with a risk of

developing end-stage liver complications (1–3). Patients

with antibodies against the hepatitis B e antigen (antiHBe) are the largest subgroup of HBV carriers worldwide, and characterized by a broad spectrum of clinical

conditions ranging from the inactive carrier (ICs) state

to chronic active hepatitis progressing to liver complications such as cirrhosis, liver failure and hepatocellular

carcinoma (HCC) (2–4). ICs must be distinguished

chronic active

prognosis and

management of these groups, with a substantial risk of

cirrhosis, clinical decompensation and HCC in the latter

(4, 5). The distinctive virological feature of patients with

chronic active HBV is infection with HBV variants that

cannot produce HBeAg because of the presence of precore or basal core promoter mutations. The livers of

these patients show persistent necroinflammation characterized by fluctuations of both viral replication and

QualeèilrischiodiprogressionedimalamaesviluppoHCC?

May 2010

LONG-TERM HEALTH OUTCOMES OF INACTIVE HBV CARR

Natural history of chronic hepatitis B

C-J Chen and H-I Yang

89 293 individuals invited

to participate in 1991–1992

23 820 enrolled in the

cohort

4155 HBsAg (+)

19 665 HBsAg (–)

3653 HBV DNA available

and anti-HCV (–)

565 HBeAg (+)

3088 HBeAg (–)

2780 HBV DNA detectable

873 HBV DNA undetectable

1520 genotype B

801 genotype C

1619 HBV DNA

84 genotype B+C

104 copies/mL

543 precore 1896 wild-type

705 BCP 1762/2764 wild-type

Supplementary

Figure 1. Flow

of participants

750 precore 1896 mutant

578chart

BCP 1762/2764

mutant in the inactive

hepatitis B virus carrier and control subcohorts. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCV, hepatitis C virus.

30

1932inacXvecarriers(HBsAg+,

HBVDNA<10,000copie/mL;

ALT<45)

Followupsemestralecon

ecografiaaddominaleedesami

ematochimici

10 000–99 999,

Figure 1 Flow of the Risk Evaluation of Viral

Load Elevation and Associated Liver Disease/

Cancer-Hepatitis B Virus (REVEAL-HBV)

study participants.

REVEALHBV

100 000–999 999,

1 000 000–99 999 999,

Ø IncidenzaHCCinacXve

carriers:64/100000

Ø Incidenzacasicontrollo

15/100000

Ø NondifferenzasignificaXva

interminidiincidenzatrai

portatoriinamviconvalori

diHBVDNAnonrilevabili

rispeboaipazienXcon

HBV<2000UI/ml

CLINICAL–LIVER,

Figure 1. Cumulative hazards of progression to hepatocellular carcinoma in the inactive hepatitis B virus

(HBV) carrier and control subcohorts.

95% CI: 0.6!4.5). For inactive HBV carriers with undetectable baseline serum HBV DNA, an alcohol drinking

A total of 1775 (91.9%) inactive HBV carriers, including

92.2% (772 of 837) and 91.6% (1003 of 1095) of those

FATTORIDIRISCHIOHCCNEIPORTATORIINATTIVI

Table 2. Multivariate-Adjusted Hazard Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) of the Risk Predictors for Newly Developed

Hepatocellular Carcinoma Included in the Cox Regression Models

All participants (n " 20,069)

Variable

Cohort

Control

Inactive HBV carrier

Undetectable HBV DNA

HBV DNA 300!10,000 copies/mL

Age (increment by every decade)

Male sex (vs female)

ALT (high-normal vs low-normal)

Alcohol drinking habit (ever vs never)

Cigarette smoking habit (ever vs never)

Hazard ratio

(95% CI)

1.0

(referent)

3.5a

5.7a

2.7

1.3

2.2

2.4

1.7

(1.5!8.3)

(2.8!11.5)

(1.9!3.8)

(0.6!2.9)

(1.2!4.1)

(1.3!4.7)

(0.8!3.5)

Inactive HBV carriers (n " 1932)

P value

Hazard ratio

(95% CI)

P value

1.0

1.6

2.6

2.9

0.5

5.0

0.5

(referent)

(0.6!4.5)

(1.4!4.6)

(0.7!11.8)

(0.1!2.3)

(1.6!15.6)

(0.2!1.6)

.362

.002

.133

.374

.005

.245

—

.005

#.001

#.001

.545

.011

.008

.151

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

" .349 for the difference between serum HBV DNA 300-10,000 copies/mL vs undetectable.

aP

CarriersofInac:veHepa::sBVirusAreS:llatRiskforHepatocellularCarcinomaandLiver-RelatedDeath.Jin-deChenetal.

GASTROENTEROLOGY2010;138:1747–1754

liver) car-

CLINICAL–LIVER,

PANCREAS, AND

BILIARY TRACT

Liverrelatedmortality

44/100000vs21/100000

FATTORIDIRISCHIODI“LIVERRELATEDDEATH”NEIPORTATORIINATTIVI

Table 3. Multivariate-Adjusted Hazard Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) of the Risk Predictors for Liver-Related Death

Included in the Cox Regression Models

All participants (n ! 20,069)

Variable

Cohort

Control

Inactive HBV carrier

Undetectable HBV DNA

HBV DNA 300-10,000 copies/mL

Age (increment by every decade)

Male sex (vs female)

ALT (high-normal vs low-normal)

Alcohol drinking habit (ever vs never)

Cigarette smoking habit (ever vs never)

Hazard ratio

(95% CI)

Inactive HBV carriers (n ! 1932)

P value

1.0

(referent)

—

2.4a

1.9a

2.3

1.8

1.9

2.1

1.7

(1.0"5.5)

(0.7"4.7)

(1.7"3.2)

(0.9"4.0)

(1.1"3.4)

(1.2"3.8)

(0.9"3.3)

.048

.188

$.001

.120

.025

.013

.094

Hazard ratio

(95% CI)

P value

1.0

0.8

2.6

1.7

0.3

5.8

1.2

(referent)

(0.2"2.7)

(1.2"5.3)

(0.3"10.9)

(0.04"2.7)

(1.5"21.9)

(0.3"4.6)

.733

.011

.552

.307

.010

.837

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

aP ! .695 for the difference between serum HBV DNA 300"10,000 copies/mL vs undetectable.

hepatocellular carcinoma was the most striking risk pre- death for inactive HBV carriers through a communitydictor for liver-related death (HRa ! 611; 95% CI: based long-term follow-up study. As antiviral therapy for

CarriersofInac:veHepa::sBVirusAreS:llatRiskforHepatocellularCarcinomaandLiver-RelatedDeath.Jin-deChenetal.

325"1151). Older age was the only significant risk pre- chronic hepatitis B was not reimbursed by national

GASTROENTEROLOGY2010;138:1747–1754

skTable

Predictors

for Newly Developed

3. Multivariate-Adjusted

Hazard Ratios (95% Confidence Intervals) of the Risk Predictors for Liver-Related Death

Liverrelateddeath

Included inHCC

the Cox Regression Models

Inactive HBV carriers (n " 1932)

Hazard ratio

Variable (95% CI)

Cohort

Control

Inactive HBV carrier

1.0

(referent)

Undetectable HBV DNA

1.6

(0.6!4.5)

HBV DNA 300-10,000 copies/mL

2.6

(1.4!4.6)

Age (increment by every decade)

2.9

(0.7!11.8)

Male sex (vs female)

0.5

(0.1!2.3)

ALT (high-normal vs low-normal)

5.0

(1.6!15.6)

Alcohol drinking

habit

(ever

vs never)

0.5

(0.2!1.6)

Cigarette smoking habit (ever vs never)

HBVDNA

All participants

(n ! 20,069)

P value

Hazard ratio

Inactive HBV carriers (n ! 1932)

neg

(95% CI)

P value

Hazard ratio

(95% CI)

P value

1.0

0.8

2.6

1.7

0.3

5.8

1.2

(referent)

(0.2"2.7)

(1.2"5.3)

(0.3"10.9)

(0.04"2.7)

(1.5"21.9)

(0.3"4.6)

.733

.011

.552

.307

.010

.837

HBVDNA<2000UI/ml

.362

.002

.133

.374

.005

.245

1.0

(referent)

2.4a

1.9a

2.3

1.8

1.9

2.1

1.7

(1.0"5.5)

(0.7"4.7)

(1.7"3.2)

Alcool

(0.9"4.0)

(1.1"3.4)

(1.2"3.8)

(0.9"3.3)

ETA’

—

.048

.188

$.001

.120

.025

.013

.094

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

ble.

aP ! .695 for the difference between serum HBV DNA 300"10,000 copies/mL vs undetectable.

hepatocellular carcinoma was the most striking risk pre- death for inactive HBV carriers through a communitydictor for liver-related death (HRa ! 611; 95% CI: based long-term follow-up study. As antiviral therapy for

325"1151). Older age was the only significant risk pre- chronic hepatitis B was not reimbursed by national

dictor independent of hepatocellular carcinoma for con- health insurance in Taiwan until 2003, the participants

trols, but not for inactive HBV carriers. Subcohort was no in this study had not received any antiviral treatment.

longer

an independent risk predictor for liver-related

CarriersofInac:veHepa::sBVirusAreS:llatRiskforHepatocellularCarcinomaandLiver-RelatedDeath.Jin-deChenetal.

Few studies in the past have addressed the long-term

GASTROENTEROLOGY2010;138:1747–1754

mortality when newly developed hepatocellular carci- follow-up of inactive HBV carriers. Gigi and colleagues10

Ø IlrischiodisviluppodiHCCperiportatoriinamviHBV

èmaggiorepercolorochepresentanounHBVDNA

misurabilerispeboacolorocherisultanoHBVDNA

NEGATIVI.TaledifferenzaNONèsignificaXva

Ø Inconsiderazionedelleevidenzeemerselasogliadi

HBVDNAconsiderataaffidabilenell’individuareil

portatoreinamvoèdi10000copie/ml

Ø L’etàèunimportantefaboredirischioperlosviluppo

diHCC

Ø IpazienXcheraggiungonoprimalostadiodiportatore

inamvohannounaminorpossibilitàdiavereuna

progressionedimalama

Tassoannualediincidenza

HCC0.06%

Tassoannualediincidenzadi

“liverrelateddeath”0.04%

Ø Valorinormali-alXdiALTnoncorrelanoconilrischiodi

HCCedimorte“fegatocorrelata”

Ø LosviluppodiHCCèilpiùimportantefaboredirischio

dimortalitàperiportatoriinamvi

CarriersofInac:veHepa::sBVirusAreS:llatRiskforHepatocellularCarcinomaandLiver-RelatedDeath.Jin-deChenetal.

GASTROENTEROLOGY2010;138:1747–1754

Natural history of chronic hepatitis B

C-J Chen and H-I Yang

Milestone 1:

Start of

decline of

HBV DNA

level

HBV DNA >108

copies/mL

HBeAg/Anti-HBe

status

Milestone 2:

HBeAg/

Anti-HBe

seroconversion

Milestone 3:

HBV DNA

decreased to

undetectable

level

Milestone 4:

Clearance of

HBsAg

HBV DNA level

HBeAg+, Anti-HBe-

HBeAg-, Anti-HBe+

Undetectable level

of HBV DNA

HBsAg+

HBsAg status

HBsAg-

ΔT

ALT level

Immune

tolerance

Immune

clearance

Residual

Figure 4 Natural history of chronic hepatitis B based on the Risk Evaluation of Viral Load Elevation and Associated Liver Disease/Cancer-Hepatitis

B Virus (REVEAL-HBV) Study findings.

MA…

Ø PazienX30-65anni

Ø Mancatodosaggioseriatodell’HBVDNA

Ø NonconsideraXigenoXpiHBV

CarriersofInac:veHepa::sBVirusAreS:llatRiskforHepatocellularCarcinomaandLiver-RelatedDeath.Jin-deChenetal.

GASTROENTEROLOGY2010;138:1747–1754

Digestive and Liver Disease 46 (2014) 427–432

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Digestive and Liver Disease

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/dld

Liver, Pancreas and Biliary Tract

Progression to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related

mortality in chronic hepatitis B patients in Italy

Donatella Ieluzzi a,b,1 , Loredana Covolo c,1 , Francesco Donato c , Giovanna Fattovich a,d,∗

a

Division of Gastroenterology and Endoscopy, Azienda Ospedaliera Universitaria Integrata, Verona, Italy

Department of Surgery, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

Institute of Hygiene, Epidemiology and Public Health, University of Brescia, Brescia, Italy

d

Department of Medicine, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

b

c

a r t i c l e

i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Ø 105pazienX(F25,M80)etàmedia30anni

Article history:

Received 11 July 2013

Accepted 10 January 2014

Available online 16 February 2014

Keywords:

Chronic hepatitis B

Cirrhosis

Hepatocellular carcinoma

Liver-related mortality

Natural history

Background: The natural history of chronic hepatitis B is variable. We evaluated some of the risk factors for

cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver-related mortality in Italian patients with chronic hepatitis

B.

Methods: A cohort of 105 untreated patients with chronic hepatitis B without cirrhosis at diagnosis was

followed prospectively for a mean period of 23 years. Clinical, histological and ultrasound examinations,

biochemical and virological tests, and causes of death were analyzed.

Results: Forty-two (40%) patients became inactive carriers and 63 (60%) showed persistent alanine aminotransferase elevation: 13 (13%) associated with HBeAg persistence, 35 (33%) with detectable serum

HBV-DNA but HBeAg-negative, 11 (10%) with concurrent virus infection and 4 (4%) with non-alcoholic

fatty liver disease. Cirrhosis incidence was 1.56/100 person-years. Older age and sustained HBV replication predicted cirrhosis occurrence independently. Hepatocellular carcinoma incidence was 2.1/100

person-years in patients who developed cirrhosis and 0.06 in those who did not. Cirrhosis occurrence

was associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (hazard ratio 20.4, 95% confidence

interval 2.54–167.5) and liver-related death (16.5, 2.0–138.8).

Conclusions: In Italian patients with chronic hepatitis B cirrhosis strongly predicts hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence and disease-related mortality, thus indicating that early antiviral treatment should be

instituted before cirrhosis occurrence.

© 2014 Editrice Gastroenterologica Italiana S.r.l. Published by Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Ø Followupsemestrale(ecografia+esamiematochimici)peri

pazienXconepaXteamvaeannualepergliinacXvecarriers

(HBeAgnegaXvi,HBVDNA<limitesogliadirilievo)

1. Introduction

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a worldwide public health problem, accounting for approximately half a million

deaths each year. The natural history of chronic HBV infection varies

from one individual to another and from one geographical area to

another, possibly due to differences in viral, host and environmental factors [1,2]. Several studies have described the characteristics,

clinical course and risk of liver-related complications of chronic

HBV infection in the Mediterranean area, but a comparison of the

results is hampered by different study design, the small number

of patients recruited, short follow-up and the heterogeneity of the

patient population in relation to the severity of chronic liver disease

at diagnosis.

A careful understanding of the clinical course and factors influencing progression of chronic hepatitis B (CHB) diagnosed at an

early stage would be particularly important for monitoring and taking evidence-based decisions on patient care in clinical practice. At

present many subjects with CHB undergo anti-viral treatment, the

standard of care consisting of life-long oral nucleos(t)ide analogues

(NAs), which have been found to suppress circulating viral loads

efficiently and can lead to regression of fibrosis [3]. At present few

data on the natural history of CHB in Western countries are available for evaluating the magnitude of the clinical benefit of antiviral

therapy.

In this study we aimed to investigate the natural history of CHB,

with emphasis on the risk of, and factors related to, clinical progression to cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and liver-related

mortality in a cohort of Caucasian patients in Italy with CHB, without histological and clinical evidence of cirrhosis at diagnosis.

Ø Duratamediadelfollowup:23.2anni(28.8perIC*)

∗ Corresponding author at: Unità Operativa Complessa di Gastroenterologia

ed Endoscopia Digestiva dO, Dipartimento di Medicina, Azienda Ospedaliera

Universitaria Integrata Verona, Piazzale A. Stefani n. 1, 37126 Verona, Italy.

Tel.: +39 045 8127257; fax: +39 045 81272014.

E-mail address: [email protected] (G. Fattovich).

*InacXvecarrier

1

105pazienX

HBsAg-;AnXHBsAg+

2duranteHBeAg+prima

dellasieroconversionead

anXHBe

2HBeAgnegaXviprima

dellanormalizzazionedelle

transaminasi

38

NESSUNODEIPORTATORIINATTIVIHASVILUPPATOHCCo

èdecedutopercausecorrelateaproblemaXcheepaXche

*NB:difabopazienXgiàarrivaticirroXciprimadellafasediianmvità

LiverInternaXonal(2016)

IncidenceofhepatocellularcarcinomainuntreatedsubjectswithchronichepaXXsB:a

systemaXcreviewandmeta-analysis

ElenaRaffem1,GiovannaFabovich2andFrancescoDonato

Ø StudilongitudinalietrialsrandomizzaXcontrollaX(pz>18anni)

Ø SoggemcondiagnosidiepaXtecronica,cirrosi,portatoriinamvi(ALT

costantementenormali,HBeAgnegaXvi,anXHBeAgposiXvi),

portatoriasintomaXci

Ø StudidacuirilevaredaXidoneialcalcolodeitassidiincidenza

Ø 66studi,347859pazienX

Ø IncidenzaHCC

Outcomemeasure

Ø RischiorelaXvoHCCperareageografica,gradodimalama,genere,età

*

R

I

S

U

L

T

A

T

I

*x100/anno

EUROPA

Portatore

asintomaXco

0.07

N.AMERICA

ASIA

0.19

0.42

Portatoreinamvo

0.03

0.17

0.06

Ø L’incidenzadiHCCaumentainmanieracrescentedalportatoreinamvoalportatore

EpaXtecronica

0.12

0.48

0.49

asintomaXco,conepaXtecronicaeconcirrosicompensata

Cirrosi

2.03

2.89

3.37

Ø compensata

Correlazioneconetàmanonconareageografica

Ø Incrementodiduevoltedelrischioperunconsumoalcolicodi60g/die

Raffetti et al.

Incidence of HCC in subjects with chronic HBV

Ø MaggiorrischiodisviluppodiHCCpergenoXpoCrispeboalB

Ø HBsAg>1000IU/ml

Fig. 3. Five-year cumulative HCC risk according to macro-area and liver disease status (Europe and East Asia). Abbreviation: HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma.

Rischiodiriamvazione

E’ ufficio di chi governa fuggire

le guerre quanto si può, ma

appartiene anche alla sapienza

loro anticipare una guerra

molesta e pericolosa per fuggirne

una più molesta e pericolosa

Guicciardini-DiscorsipoliXci

HBsAg<1000,HBV

DNA<2000,normalALT

IMMUNOSOPPRESSIONE

IncrementoHBVDNA

RIPRISTINOIMMUNITA’

immunoricosXtuzione

IncrementoALT

EPATITEACUTA/FULMINANTE

KempinskaA,etall.Reac:va:onofhepa::sB

infec:onfollowingallogeneicbonemarrowLong-termsurveillance

ofhaematopoie:cstemcellrecipientswithresolved

transplanta:onina

TheoriginofIgG

hepa::sB:highriskofviralreac:va:oneveninarecipientwith

Changesinserologicmarkersofhepa::sBfollowingautologous

hepa::sB-immunepa:ent:casereportandreviewoftheliterature.

produc:onandhomogeneousIgGcomponentsa^erallogeneic

Severereac:va:onofhepa::sBvirusinfec:oninapa:ent

avaccinateddonor.JViralHepat2007;

hematopoie:cstemcelltransplanta:on.BiolBloodMarrow

ClinInfectDis2005;41:1277–1282

bonemarrowtransplanta:on.Blood1996;87:818–826

withhairycellleukemia:shouldlamivudineprophylaxisberecommended

Hepa::sBvirusreac:va:oninacaseofnon-Hodgkin’s

Transplant2007;13:463–468

toHBsAg-nega:ve,an:-HBc-posi:vepa:ents?

lymphomatreatedwithchemotherapyandrituximab:necessityof

Fatalhepa::s

Progressivedisappearanceofan:-hepa::sBsurface

Infec:on2006;34:282–284

prophylaxisforhepa::sBvirusreac:va:oninrituximabtherapy.

Breac:va:ona^erautologousbonemarrowtransplanta:on.

an:genan:bodyandreverseseroconversiona^erallogeneic

Thehepa::s

LeukLymphoma2004;45:627–629

BoneMarrowTransplant1989;4:207–208\

hematopoie:cstemcelltransplanta:oninpa:entswithprevious

Bviruspersistsfordecadesa^erpa:ents’recoveryfromacute

Fulminanthepa::sduetoreac:va:onof

hepa::sBvirusinfec:on.Transplanta:on2005;79:616–619

viralhepa::sdespiteac:vemaintenanceofacytotoxicT-lymphocyte

chronichepa::sBvirusinfec:ona^erallogeneicbonemarrow

Hepa::s

response.NatMed1996;2:1104–1108

transplanta:on.DigDisSci.1988;33:1185–91.

Bvirusreac:va:ona^erallogeneicbonemarrow

Lamivudinetherapyforchemotherapyinduced

transplanta:oninapa:entpreviouslycuredofhepa::sB.

reac:va:onofhepa::sBvirusinfec:on.AmJGastroenterol.

Hepa::s

GastroenterolClinBiol.1999;23:770–4.

Reac:va:onofhepa::sBa^ertransplanta:on

Bvirusreac:va:ona^erallogeneicbonemarrow

1999;94:249–51.

inpa:entswithpre-exis:ngan:-hepa::sBsurfacean:gen

Occurrenceandmanagementofhepa::sBvirus

transplanta:oninapa:entpreviouslycuredofhepa::sB.

an:bodies:reportonthreecasesandreviewoftheliterature.

reac:va:onfollowingkidneytransplanta:on.ClinNephrol.

GastroenterolClinBiol.1999;23:770–4.

Transplanta:on.1998;66:883.

Reac:va:onofhepa::sB

1998;49:385–8.

a^ertransplanta:onopera:ons.Lancet.1977;68:105–12

Hepa::sBvirusandhepa::sB-relatedviralinfec:onin

Reac:va:onofhepa::sBvirusinHBsAgnega:ve

renaltransplantrecipients.Gastroenterology1988;94:151–156

pa:entswithmul:plemyeloma:twocasereport

HepaXXsBreacXvaXoninthesemngofchemotherapyand

immunosuppression-prevenXonisbeberthancure

YoshidaetalIntJHematology.2010Jun,91(5):844-9

WJH2015

Tra)amentodell’epa2teBcronica:raccomandazionidaunworkshopitaliano-

Diges2veandLiverDisease40(2008)603-617

La profilassi è indicata:

Nei portatori inattivi di HBsAg sottoposti a chemioterapia antitumorale o a

trattamento immunosoppressivo ad alto rischio: anti-TNF, anti CD20, anti

CD56 a steroidi a dosaggi medio elevati (>7.5mg/die) per periodi

prolungati, ciclofosfamide, metotrexato, leflunomide, ciclosporina,

tacrolimus, azatioprina, micofenolato

I portatori cronici inattivi e i pazienti HBsAg negativi e anti-HBc-positivi

devono essere sottoposti a profilassi fin dall’inizio del trattamento

immunosoppressivo o, se possibile, a partire da 2-4 settimane prima che

cominci la somministrazione dei farmaci immunosoppressori (CIII)

La profilassi mirata deve essere iniziata al momento della riattivazione

della malattia (HBV-DNA >2000UI/ml) nei portatori di HBsAg, e

immediatamente dopo la sieroconversione nei pazienti che diventano

HBsAg positivi (CIII)

Risk stratification for HBV reactivation

Drugs

High

Disease

Oncohematology

and BMT

IBD

Medium

TNFa-inhibitors

Other biological DMARDs

Leflunomide

Methotrexate

Cyclophosfamide

HBsAg+

Combination therapies

Medium/high-dose prednisone (>7.5 mg/die)

Null Low

Rheum

RISK

HIV

HBsAg+

anti-HBc+

Rituximab

combined

therapy

SOTs

Virus

Calcineurin inhibitors

Azathioprine

6-mercaptopurine

Low-dose prednisone (<7.5 mg/die)

Sulfasalazine

Hydroxychlorochine

Marzano A et al., DLD 2007 (2011)

RischiodiriamvazioneneipazienX

immunocompromessi

BonemarroworstemcelltransplantaXon

HBsAg-posiXve

HBsAg-negaXve,anX-HBc-posiXve

32–50%

upto50%

AnX-CD20monoclonalanXbodies(rituximab)

HBsAg-posiXve

HBsAg-negaXve,anX-HBc-posiXve

50-80%

18%

SolidorgantransplantaXon

HBsAg-posiXve

HBsAg-negaXve,anX-HBc-posiXve

50-90%

0.9-5%

39-41%

3%

39%

5%

Systemiccancerchemotherapy

HBsAg-posiXve HBsAg-negaXve,anX-HBc-posiXve

TNF-alfaantagonists

HBsAg-posiXve HBsAg-negaXve,anX-HBc-posiXve

Hwang and Lok Nat Rev Gastroenterol 2013

Hepat Mon. 2016 April; 16(4):e35810.

doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.35810.

Review Article

Published online 2016 March 26.

Hepatitis B Reactivation During Immunosuppressive Therapy or

Cancer Chemotherapy, Management, and Prevention: A

Comprehensive Review

Soheil Tavakolpour,1 Seyed Moayed Alavian,1,* and Shahnaz Sali2

1

Baqiyatallah Research Center for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Baqyiatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, IR Iran

Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine Research Center, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, IR Iran

2

*

Corresponding author: Seyed Moayed Alavian, Baqiyatallah Research Center for Gastroenterology and Liver Diseases, Baqyiatallah University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, IR

Iran. Tel/Fax: +98-2181264070, E-mail: [email protected]

Tavakolpour

Received 2015 December 26; Revised 2016 January 17; Accepted 2016 January 27.

Ø Lalamivudinapuòessereconsideratacomelapiùcomunescelta

Abstract

perlaprofilassineipazienXHBV

avoided in cases under HSCT, even in the presence of complete remission (52, 61). Thus, prophylaxis longer than

24 months was recommended for these patients (54). On

the issue of HSCT, several studies have reported HBVr after

more than

Context: Due to the close relationship between the immune system and the hepatitis B virus (HBV) replication, it is essential

to 12 months, reaching a peak of 91 months (27, 54,

56, 61).

monitor patients with current or past HBV infection under any type of immunosuppression. Cancer chemotherapy, immunosupConsidering the high resistance to lamivudine (LAM),

in are

addition

pressive therapies in autoimmune diseases, and immunosuppression in solid organ and stem cell transplant recipients

the to various reported cases with a risk of reactivation following more than 6 months from the cessation

major reasons for hepatitis B virus reactivation (HBVr). In this review, the challenges associated with HBVr are discussed according

of immunosuppressive therapy or chemotherapy, it is recommended

to the latest studies and guidelines. We also discuss the role of treatments with different risks, including anti-CD20 agents,

tumor that referenced HBV antiviral agents, such as

entecavir (ETV) and TNV should be used in therapies that

necrosis factor-alpha (TNF- ) inhibitors, and other common immunosuppressive agents in various conditions.

need long-term prophylaxis. Recommendations of various

bodies

associated with HBVr are shown in Table 2.

Evidence Acquisition: Through an electronic search of the PubMed, Google Scholar, and Scopus databases, we selected the

studies

In a meta-analysis, LAM prophylaxis in HBsAg carriers

associated with HBVr in different conditions. The most recent recommendations were collected in order to reach a consensus

on

with breast cancer under chemotherapy was introduced as

an effective option in the reduction of HBVr (95). Based on

how to manage patients at risk of HBVr.

a systematic review, LAM prophylaxis had appeared as an

Results: It was found that the positive hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), the high baseline HBV DNA level, the positive effective

hepatitis

option in the reduction of HBVr in HBsAg-positive

B virus e antigen (HBeAg), and an absent or low hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) titer prior to starting treatment are lymphoma

the most patients undergoing chemotherapy. After that,

preventing reactivation caused a decrease in the disrupimportant viral risk factors. Furthermore, rituximab, anthracycline, and different types of TNF- inhibitors were identified

as the

tion of the chemotherapy (96).

high-risk therapies. By analyzing the efficiency of prophylaxis on the prevention of HBVr, it was concluded that those with a high

In risk

another report, anti-HBc-positive patients under immunosuppressive therapy were included (97). These paof antiviral resistance should not be used in long-term immunosuppressants. Receiving HBV antiviral agents at the commencement

tients suffered from various autoimmune diseases. Among

of immunosuppressant therapy or chemotherapy was demonstrated to be effective in decreasing the risk of HBVr. Prophylaxis

could

those

who had received antiviral therapy, none indicated

in HBV DNA levels, while 11.5% of the control group

also be initiated before the start of therapy. For most immune suppressive regimes, antiviral therapy should be kept up foraatrise

least

6

did experience an increase. ALT elevation was significantly

months after the cessation of immunosuppressive drugs. However, the optimal time of prophylaxis keeping should be increased

lower in in

the antiviral prophylactic group. Additionally, one

in the control group showed reverse seroconvercases associated with rituximab or hematopoietic stem cell transplants. According to the latest studies and guidelines frompatient

different

sion. In contrast, no reverse seroconversion was observed

bodies, recommendations regarding screening, monitoring, and management of HBVr are outlined.

in the prophylactic group.

LAM can be considered as the most common prophyConclusions: Identification of patients at the risk of HBVr before immunosuppressive therapy is an undeniable part of treatment.

laxis in HBV patients. However, there is a considerable risk

Starting the antiviral therapy, based on the type of immunosuppressive drugs and the underlying disease, could lead to better

manof LAM

resistance risk in patients with active HBV. Based on

the literature, LAM is an appropriate choice in cases with

agement of disease.

high viral replication that need short-term treatments. In

contrast, it was not recommended for HBsAg carriers with

Hepatitis B Virus, Reactivation, Immunosuppression, Rituximab, Prophylaxis

detectable HBV DNA levels at baseline, who are candidates

for long-term immunosuppressive therapy. Accordingly,

it can be concluded that LAM prophylaxis is a reasonable

choice for OBI/resolved HBV patients.

LAM is more common in countries with a high preva-

Ø Lalamivudinarappresentaunasceltaappropriataneicasicon

elevatareplicaviralechenecessitanoditrabamenXdibreve

↵

durata

Ø SceltaragionevolenegliOBI

Keywords:

↵

La lamivudina si è mostrata efficace nella profilassi della riacutizzazione

HBV(0.9% vs 25-85% dei non trattati negli studi retrospettivi e 5% vs 24 negli

studi prospettici)

2008

La profilassi con lamivudina è indicata nei pazienti HBsAg+ con HBV DNA <

2000 UI/ml,; nei pazienti con HBV DNA> 2000UI/ml , che devono essere

sottoposti a cicli di durata maggiore o ripetuti, è indicato l’utilizzo di analoghi

ad alta barriera genetica (tenofovir o entecavir)

2012

La terapia profilattica antivirale è raccomandata per i portatori di HBV all’

inizio della terapia ed almeno sei mesi dopo, i farmaci ad alta barriera genetica

sono raccomandati quando previsti trattamenti di lunga durata o quando

vengono utilizzati farmaci ad alto rischio come il Rituximab

2016

La profilassi è indicata nei pazienti HBsAg che devono essere sottoposti a

chemioterapia o a regimi di immunosoppressione sia durante che per 6-12

mesi dopo la fine del trattamento

2016

with normal baseline ALT has been reported to be higher during

the first year (15–20%) [12,14] and declines after 3 years of follow-up [9,14,15], frequent monitoring during the first 1–3 years

is critical in determining whether a patient has PNALT.

Besides the frequency of determinations and duration of follow-up, definition of PNALT should include standardized criteria

for the upper limit of normal (ULN) of ALT. Some investigators

have suggested that lower cut-offs than the traditional values

defined by most diagnostic laboratories (around 40 IU/L) should

be used. These suggestions were derived from studies based on

single ALT values in Italian blood donors [16], the associations

between normal ALT and increased rates of liver related deaths

in Koreans applying for life insurance [17], and high serum HBV

DNA levels or increased risks of complications of liver disease

tional cut-offs for the ULN of ALT values in patients with

HBeAg-negative chronic HBV infection.

Severe liver histological lesions were rare among HBeAg-negative patients with truly PNALT. In the four studies with good or

acceptable definitions of PNALT [7,8,11,12], more than a minimal

(always mild) inflammatory activity was detected in only 3% and

more than mild fibrosis always with minimal inflammatory activity in only 5% (moderate fibrosis: 4.5%, severe fibrosis: 0.5%, cirrhosis: 0%) of 215 patients with serum HBV DNA 620,000 IU/

ml. The prevalence of mild inflammatory activity and moderate

fibrosis was 7% and 10% among patients with HBV DNA levels

between 2000 and 20,000 IU/ml and 1.4% and 1% among those

with HBV DNA levels <2000 IU/ml. Similar mild histological findings in HBeAg-negative patients with HBV DNA 620,000 IU/ml

Qualefollowup?

Review

Follow-up and indications for liver biopsy in HBeAg-negative

chronic hepatitis B virus infection with persistently normal ALT:

A systematic review

George V. Papatheodoridis1,⇑, Spilios Manolakopoulos1, Yun-Fan Liaw2, Anna Lok3

1

HBeAg-negative patient with normal ALT at baseline

2nd Department of Internal Medicine, Athens University Medical School, ‘‘Hippokration’’ General Hospital of Athens, Greece; 2Liver Research

Unit, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung University College of Medicine, Taipei, Taiwan; 3Division of

Gastroenterology and Hepatology, University of Michigan Health System, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

ALT every 3-4 mo for one year

+ serum HBV DNA determination