Poste Italiane S.p.A. Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale — D.L. 353/2003 (conv. in Legge 27/02/2004 n. 46), Articolo 1, Comma 1, DCB – Milano

951 • October 2011 / Renzo Piano’s monastery at Ronchamp: two opinions / Preston Scott Cohen’s Tel Aviv Museum

of Art extension / In Caracas, Urban-Think Tank designs a school for autistic children / Jonathan Olivares reviews

the design of digital storage / Project Japan: revisiting the Metabolist movement / Sam Jacob on Rupert Murdoch’s

architectural metaphors / Nine books selected by Hans Ulrich Obrist / Dan Graham’s horoscope (Libra)

A € 22.70 / B € 18.20 / Canton Ticino CHF 28.00

CH CHF 34.00 / D € 23.00 / E € 19.95 / F € 16.00

GR € 18.00 / I € 10.00 / L € 16,00 / J ¥ 3,780 (inc.tax)

NL € 16.50 / P € 17.00 / UK £ 16.50 / USA $ 33.95

domus 951

October 2011

Arrampicata

sugli specchi

A rock in a

hard place

Progetto • Design

Cino Zucchi Architetti

Park Associati

Testo • Text

Luka Skansi

Foto • Photos

Alberto Sinigaglia

•

Centro logistico e showroom, la nuova sede della

Salewa trasforma le attività legate all’alpinismo in eventi

sociali e spazi di qualificazione dell’ambiente industriale

• With a logistical centre and showroom, the new

Salewa Headquarters transforms mountaineering

and climbing sports into social events and opportunities

to improve the industrial environment

Il nuovo complesso ospita

la più grande palestra

d’arrampicata d’Italia.

Grazie al portale d’ingresso

con una parete scorrevole è

stato creato un microclima che

dà agli sportivi la sensazione di

essere all’aria aperta

• The complex houses the

largest climbing gym in Italy.

Thanks to the large entry

portal with its sliding wall, a

microclimate has been created

that gives users the sensation

of being outdoors

Bolzano

La responsabilità di un landmark

Nella nuova sede della Salewa a Bolzano si respira l’aria di

una vecchia ma ‘eroica’ Italia. Quella degli anni Cinquanta e

Sessanta, fatta di grandi e piccoli industriali e imprenditori, che

costituivano eccellenze nei propri settori economici e che intuivano

nell’architettura una potenzialità, un grande strumento per

esprimere, nel più ampio senso del termine, la propria identità

aziendale e culturale. Per non scomodare il solito, e in questo caso

forse eccessivo, esempio di Adriano Olivetti, basterebbe ricordare

le numerose iniziative edilizie di Livio Zanussi, di Vittorio Necchi,

di Giuseppe Brion, o dei gruppi Burgo e Fantoni, per rendersi conto

della qualità della committenza industriale italiana di quel periodo

e della sua diffusione sul territorio. Si trattava di committenti che

creavano le proprie sedi industriali, parallelamente a un fiorente

sviluppo aziendale, in collaborazione con i migliori architetti,

artisti, ingegneri e paesaggisti nazionali contemporanei: per loro

costruire uno stabilimento o un complesso per uffici significava

46

47

Bolzano, IT

domus 951

trasmettere, attraverso sofisticate operazioni architettoniche,

un vero e proprio modo di essere e d’intendere l’azienda e il

mercato. Per molti significava ribadire che la propria azienda era

fatta di uomini e non solo di strategie commerciali; che essa era

costruita su prodotti che esprimevano specifici concetti e valori,

e non erano solo merce che necessitava di operazioni di brand

marketing. Particolare attenzione al luogo quotidiano del lavoro

dei propri impiegati e lavoratori e a un’umanizzazione degli spazi

collettivi correva parallelamente a una sofisticata organizzazione

del lavoro, della produzione e della distribuzione. Gli stabilimenti e

gli edifici per uffici rappresentavano una sorta di completamento

quasi naturale dell’organizzazione industriale e della costruzione

dell’immagine aziendale, non etichettabile semplicemente come

temi (commerciali, funzionali, paesaggistici, tecnologici,

ecologici, spaziali e visuali) che hanno reso profondo il contenuto

stesso del messaggio.

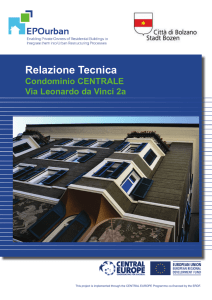

Il complesso sorge sul bordo meridionale della zona industriale

di Bolzano, a ridosso dell’autostrada del Brennero. È il “landmark

di una provincia”, dichiara Oberrauch in un curioso video di

presentazione dell’edificio, realizzato in occasione della Biennale

di Venezia del 2010, “e io ne sento la responsabilità”. Segna infatti

fortemente la soglia tra l’autostrada, l’edificato e la densa maglia

dei frutteti e dei vigneti. Ed è qui che l’operazione si muove su

un terreno decisamente attuale, distanziandosi non tanto dai

modelli quanto dalle realtà degli illustri esempi di architettura

industriale degli anni Cinquanta e Sessanta. L’edificio mostra

operazione di rappresentazione o marketing.

Heiner Oberrauch, presidente dell’azienda Salewa ed energico

committente del nuovo complesso polifunzionale a opera di

Cino Zucchi Architetti e Park Associati, è un imprenditore di

questo stampo. L’edificio, vero landmark territoriale nel delicato

contesto della valle dell’Adige, rappresenta per diversi motivi

le specificità del suo gruppo aziendale e le sue caratteristiche di

committente: in esso si sono materializzati, grazie soprattutto

all’abilità dei progettisti e al loro reciproco confronto, il modo

d’intendere il paesaggio antropizzato, il modo d’instaurare un

rapporto con la natura, la modalità con la quale rappresentare

la sua struttura organizzativa e il senso dei suoi prodotti e, non

da ultimo, il rapporto economico e sociale da instaurare con il

proprio territorio. Architetti e committenza hanno collaborato a

creare un edificio fortemente rappresentativo, un vero marchio

architettonico. Tuttavia, si è trattato di un’operazione condotta

senza alcun tipo di volgarizzazione del messaggio commerciale;

al contrario, l’edificio è il risultato di una riflessione sui molteplici

in tutta la sua fisicità il suo atteggiamento ambientale, che non

è soltanto ecologico (l’edificio è parzialmente autonomo dal

punto di vista energetico, avendo sul tetto il più grande campo di

pannelli fotovoltaici del Trentino-Alto Adige), ma anche visivo:

non cerca mimesi nel territorio, bensì un ambientamento della

sua massa nel paesaggio della valle dell’Adige.

La fisicità e la massività vengono interpretate attraverso

due strategie: da una parte attraverso la scomposizione e la

modellazione dei diversi volumi che costituiscono il complesso,

dall’altra lavorando sulla materialità dell’involucro, sul suo

disegno e sul suo cromatismo. L’involucro è costituito da una serie

di pannelli forati in alluminio. Tre gradazioni cromatiche e tre

diversi disegni di forature costituiscono gli elementi linguistici

e grafici che permettono ai progettisti di costruire una più

complessa variazione visiva della superficie. Il dispiegamento

dei pannelli segue il disegno dei filari adiacenti, costruendo

un’analogia visiva con il pattern del territorio agricolo. Ma è a

grande scala che il gioco cromatico raggiunge il suo effetto più

48

•

Salewa Headquarters

Per rispondere al programma

multifunzionale e relazionarsi

al contesto misto, industriale

e naturale, il complesso adotta

continue variazioni di scala.

Il dinamismo che si genera

favorisce la percezione visiva

dall’autostrada

• To satisfy the multipurpose

programme and relate to

its mixed, industrial and

natural context, the complex

uses continual variations of

scale. The resulting sense of

movement enhances its visual

perception from the motorway

•

•

Le pareti vetrate continue dei

corpi degli uffici sono rivolte

a nord verso le montagne

e aprono agli ambienti di

lavoro una panoramica sul

paesaggio naturale.

La torre raggiunge l’altezza

di 47 metri

• The continuous glazed

walls of the office blocks face

north towards the mountains

and open up the workplaces

to a panoramic view of the

natural landscape. The tower

reaches a height of 47 m

Il ‘Salewa Cube’ con la

palestra d’arrampicata si

assottiglia nell’ala più bassa

vetrata che accoglie lo

showroom aziendale. Per i

climber sono a disposizione

2.000 m2 di superficie e 180

tracciati diversi. C’è anche

una via ferrata, mentre la

parete esterna Dry Tooling

permette l’allenamento con

la piccozza

• The “Salewa Cube” with its

climbing gym becomes thinner

in the lower glazed wing,

which accommodates the

company showroom. Climbers

have access to 2,000 m2 of

surface and 180 different

routes. There is also an iron

route, while the Dry Tooling

external wall enables climbers

to practise using the ice-axe

October 2011

interessante: su un principio di mimetismo d’ispirazione quasi

militare, l’involucro si comporta come una macchia in sintonia

con il territorio, inserendosi in esso attraverso l’assorbimento delle

gradazioni verde-grigio, che caratterizzano i fronti alberati delle

montagne circostanti.

Il manto del rivestimento copre i diversi volumi del complesso (i

vari ‘contenitori funzionali’), rendendo difficile la loro leggibilità

dall’esterno. Un trattamento che fa sì che l’edificio non abbia, nel

suo interno, visuali dirette verso l’esterno, ma solo filtrate dalle

bucature della pannellatura. Tuttavia, verso nord il complesso

cambia faccia: l’involucro dell’alluminio lascia spazio a una

serie di pareti interamente vetrate. Questo doppio registro,

che risponde a decisioni prevalentemente paesaggistiche (la

si relaziona non più a una scala paesaggistica, quanto urbana.

I volumi sono qui modellati con l’intenzione di costruire un

recinto fisico, nel quale ospitare una piazza. La piazza, realizzata

in collaborazione con l’artista altoatesina Margit Klammer,

leggermente sopraelevata rispetto alla strada, è il fulcro spaziale

per gli affacci di una serie di ambiti funzionali come il foyer, gli

uffici e lo showroom dell’azienda. Uno spazio urbano di qualità, che

può condizionare anche il successivo sviluppo dell’area industriale.

Ma la vera porta dell’edificio verso la città, in termini funzionali,

visivi e in fondo anche simbolici, è la grande palestra di roccia

indoor, la più grande di questo tipo realizzata in Italia. Un corpo

di altezza variabile fino a un massimo di 19 m che ha al suo

interno 1.850 m² di superficie su cui poter svolgere le vie di diverse

facciata settentrionale lucida e trasparente, gli altri affacci

sostanzialmente ciechi) è reso possibile da una complicata ma

accurata disposizione funzionale. Verso sud sono collocati i diversi

magazzini automatizzati, vero spettacolo tecnologico della Salewa.

Essi occupano la gran parte della volumetria del complesso visto

dall’autostrada e sono illuminati zenitalmente. A questo scomparto

sono addossate verso nord tutte le altre funzioni aziendali, disposte

in corpi a torre di diverse altezze: vari uffici, la direzione, un asilo

e una palestra aziendale, appartamenti per ospiti e per il custode,

una mensa si affacciano liberamente su un suggestivo panorama

della valle di Bolzano con, sullo sfondo, il potente teatro montano.

Un ampio terrazzo viene invece intagliato nella volumetria sul

fronte sud, sopra i magazzini. A ridosso delle cucine, questo spazio è

pensato come zona di ristoro o di pausa: anche questo luogo gode di

una speciale inquadratura delle montagne.

Un’ulteriore tema progettuale che gli architetti usano per definire

la forma dell’edificio è il disegno del suo affaccio verso la città, o

meglio, verso la zona industriale. Si tratta del fronte vetrato, che

difficoltà, da un livello base a un livello superiore per competizioni

agonistiche. Si tratta di un luogo già particolarmente ambito,

anche per il suo affaccio sul paesaggio, con un portale apribile in

qualsiasi momento dell’anno, anche nelle tiepide o fredde giornate

invernali o di mezza stagione, per permettere all’arrampicatore il

diretto contatto con l’esterno.

Questo edificio può, in un certo senso, essere considerato opera

unica, prodotto di un attivo e condizionante processo di selezione

operato dalla committenza che va dalla scelta del luogo (Bolzano),

agli architetti (attraverso un concorso di idee a inviti a due fasi,

che ha visto coinvolti progettisti del calibro di Perrault, Bearth

& Deplazes, Pichler, Mahlknecht & Mutschlechner, Tscholl),

ai professionisti, agli esecutori e a tutti i tecnici (attraverso

gare d’appalto) che hanno portato alla definizione finale della

complessa macchina funzionale.

—

Luka Skansi

Storico dell’architettura, iuav

49

Bolzano, IT

Salewa Headquarters

domus 951

October 2011

12

4

10

13

2

11

5

5

9

6

8

9

8

13

16

1

15

1

12

1

7

2

8

3

5

d1

d2

4

7

d2

6

d1

1

Uffici e mensa con cucina · Offices and canteen with kitchen

2 Showroom

3 Palestra d’arrampicata e area boulder

· Climbing gym and boulder area

4 Tetto verde / Sotto: magazzino meccanizzato

· Green roof / Below: mechanised warehouse

5 Terrazzo · Terrace

6 Pannelli fotovoltaici / Sotto: magazzino libero

· Photovoltaic panels / Below: free warehouse

7 Magazzino automatizzato · Automated warehouse

8 Bistro

Design Architects

Energytech Ingegneri S.r.l.

Georg Felderer

Design Team

Site Supervision

Cino Zucchi Architetti

Cino Zucchi

Park Associati

Filippo Pagliani, Michele Rossi

with Elisa Taddei (Project

architect), Alice Cuteri,

Lorenzo Merloni, Marco

Panzeri, Davide Pojaga,

Alessandro Rossi, Giada

Torchiana, Fabio Calciati

(rendering)

Structural Engineering

Kauer & Kauer Ingenieure

Georg Kauer, Ulrich Kauer

Electrical Engineering

Energytech Ingegneri S.r.l.

Gabriele Frasnelli

50

Mechanical Engineering

Cino Zucchi Architetti,

Park Associati

Plan Team GmbH

Johann Röck,

Rupert Cristofoletti

Climbing Hall Consultant

Ralf Preindl

Artistic Intervention

Margit Klammer

Contractors

ZH SpA (civil works), Stahlbau

Pichler (faCade), Walltopia,

Sintroc (climbing wall),

Zumbobel SpA, (lighting)

Client

Salewa SpA

Lamiera alluminio verniciato 30/10

10

Fissaggio puntuale · Clamping

Area totale · Site area

30,595 m2

· Painted aluminium sheet 30/10

11

Guaina impermeabilizzante con scossalina metallica

Cubatura totale · Total cubic volume

146,248 m3

2 Anima alluminio 10/10 · Aluminium core 10/10

antirumore · Waterproofing sheath with noise-

Costo · Cost

€40 million

3 Sigillatura strutturale · Structural sealing

abating metal ridge cap

Fase progettuale · Design phase

04/2007—10/2008

Costruzione · Construction

07/2009—10/2011

1

4 Serigrafia · Silkscreening

12

Parete prefabbricata a secco · Prefabricated dry wall

5 Forex 5 mm · Forex 5 mm

13

Sistema isolato di aggancio della sottostruttura in

6 Sigillatura · Sealing

acciaio zincato · Insulated clamp system for the

7 Parete a secco · Dry wall

8 Lamiera acciaio zincato 8/10 · Galvanised steel plate 8/10

galvanised steel substructure

14

9 Lamiera in alluminio 30/10 mm elettrocolorata forata,

Sottostruttura in alluminio elettrozincato

· Substructure in electro-galvanised aluminium

ø30 ø50 ø70 mm · Aluminium sheet 30/10 mm thick

15

Piastra metallica · Metal slab

electrocoloured, ø30 ø50 ø70 mm

16

Solaio in cemento armato a vista

· Floor slab in unfaced reinforced concrete

pianta delle coperture

roof plan

0

10m

B1

B2

A

C

dettagli

details

sezione a—a’

section a—a’

0

0

5cm

5m

51

Salewa Headquarters

Bolzano, IT

The new Salewa Headquarters in Bolzano exudes the air of

an old but “heroic” Italy: that of the 1950s and ’60s, created by

major and minor industrialists and entrepreneurs who brought

excellence into their economic sectors. It was they who intuited

that architecture could be a potential, a great vehicle through

which to express, in the widest sense of the term, their corporate

and cultural identities. Leaving aside the usual, and in this case

perhaps excessive, example of Adriano Olivetti, one need only

recall the numerous building initiatives undertaken by Livio

Zanussi, Vittorio Necchi, Giuseppe Brion, or by the Burgo and

Fantoni groups, to appreciate the quality of Italian industrial

elaborate organisation of work, production and distribution.

Their factories and office buildings represented an almost natural

completion of their industrial organisation and of the building

of a corporate image, not just labelled as a representation or

marketing operation.

Heiner Oberrauch, CEO of the Salewa corporation and energetic

client of the new multifunctional complex designed by Cino

Zucchi Architects and Park Associati, is an entrepreneur of that

ilk. The building, truly a landmark within the delicate context

of the Adige valley, represents, for diverse reasons and themes,

the peculiarities of his corporate group and its characteristics

as a client. In it are materialised, thanks above all to the ability

of the architects and to their mutual comparison, the approach

•

Responsibility for a landmark

domus 951

clients of that period and of their widespread effect. These were

clients who created their own industrial headquarters, parallel to

a flourishing corporate growth and in collaboration with the best

contemporary Italian architects, artists, engineers and landscape

designers. For them, building a factory or an office complex meant

transmitting, through sophisticated architectural operations,

an authentic way of being, of understanding a company and

its market. For many it meant stating that their company was

made up of people and not only of sales strategies; that it was

built on products expressing specific concepts and values, and

not simply on goods to be brand marketed. Particular attention

to the everyday workplace of their staff and workers, and the

humanisation of collective corporate spaces went with an

to the anthropised landscape, the manner of establishing a

rapport with nature, the procedure with which to represent

its organisational structure and the sense of its products;

and, not least, the economic and social relationship to be

established with its surroundings. The architects and the client

joined forces to create a distinctly representative building, a

genuine architectural trademark. This, however, has been an

operation conducted without the slightest vulgarisation of the

commercial message. On the contrary, the building is the result

of a reflection on the many different themes—commercial,

functional, landscape design, technological, ecological, spatial

and visual—that have made the actual contents of that message

complex and profound.

•

•

La geometria spezzata

dell’involucro metallico crea

assonanza con l’orografia

circostante. La pelle

dell’edificio è realizzata con

pannelli di alluminio forato

ed elettrocolorato

• The broken geometry

of the outer metal frame

creates an assonance with

the configuration of the

surrounding mountains.

The building’s skin is

built with perforated and

electrocoloured aluminium

panels

In alto: una parte della copertura

è un giardino pensile, con una

zona verde, una terrazza e un

camminamento in legno.

Sotto: il magazzino

automatizzato, con struttura

prefabbricata e microshed

• Above: part of the roof is a

hanging garden, with a green

zone, a terrace and a wooden

walkway. Below: the automated

warehouse, built with a

prefabricated structure, has

microshed skylights

52

October 2011

The complex is situated on the south edge of Bolzano’s

industrial zone, next to the Brennero motorway. It is the

“landmark of a province”, states Oberrauch in a curious

video presentation of the building made in concomitance

with the 2010 Venice Biennale, “and I feel responsibility

for it”. It strongly marks in fact the threshold between

the motorway, the built area and the dense fabric of

orchards and vineyards. It is here that the operation

moves on a decidedly topical ground, keeping its distance

not so much from the models as from the reality of the

illustrious examples of industrial architecture of the ’50s

and ’60s. The building in all its physicality displays its

environmental attitude. This is not only ecological (the

Sulla copertura di uno dei

magazzini sono disposti 1.666

moduli fotovoltaici Sunpower

BLK, per una superficie

totale di 2.073 m2. La stima

dell’energia che sarà prodotta

in un anno è di 400.000 kWh

• Set on the roof of one of

the warehouses are 1,666

Sunpower BLK photovoltaic

modules, occupying a total

surface of 2,073 m2. An

estimated 400,000 kWh will

be produced each year

building is partially self-sufficient in terms of energy,

with the largest stretch of photovoltaic panels on its roof

to be seen anywhere in Trentino Alto Adige), but visual

too. It does not attempt to disguise itself but rather to

relate its mass to the landscape of the Adige valley.

The physicality and massiveness are interpreted with

two strategies. On the one hand through the breakingdown and modelling of the different volumes of which

the complex is composed, and on the other by working

on the materiality of its cladding, design and colour.

The cladding consists of perforated aluminium panels.

Three shades of colour and three different patterns of

perforation comprise the linguistic and graphic elements

that have allowed the architects to construct a more

complex variation of the surface. The arrangement of

panels follows the pattern of adjacent rows of trees, thus

constructing a visual analogy with that of its agricultural

context. But it is on a large scale that the play of colour

attains its most interesting effect: on a camouflage

principle of almost military inspiration, the outer frame

behaves like a stain in harmony with its surroundings,

merging into it through the absorption of grey-green

shades from the woods on the surrounding mountains.

The cladding of the complex’s various volumes—the

various “functional containers”—makes their legibility

difficult from the outside. As a result of this treatment the

building has no direct views of the exterior from within,

but only those filtered by the holes in the panelling.

However, to the north the building changes face. The outer

aluminium front leaves room for entirely glazed walls.

And this dual feature, arising from mainly landscape

decisions—the shiny and transparent north front, and

the other sides mostly blind— is made possible by a

complicated but effective functional arrangement. Located

to the south are the various automated warehouses, truly a

technological marvel staged by Salewa. These occupy most

of the complex’s volumetry seen from the motorway and

are lit from above. Next to this department to the north

are all the other corporate functions, set in tower units of

different heights.

Housing various offices, management, a nursery and a

company gymnasium, guest and janitor accommodation

and a canteen, they look freely over a delightful panorama

of the Bolzano valley with its impressive mountain scenery

in the background. An extensive terrace is cut into the

volumetry of the south front, above the warehouses. Next

to the kitchens, this space is seen as a refreshment or rest

zone. And this place too enjoys a special picture view of the

mountains.

A further theme used by the architects to define the

building’s form is the design of its city front, namely that

facing the industrial zone. This is the glazed front, relating

no longer to a landscaped but rather to an urban scale. The

volumes here are modelled with the intention of building

a physical enclosure, in which to contain a plaza. The plaza,

created in collaboration with the South Tyrolean artist

Margit Klammer and slightly raised above the street, is the

spatial fulcrum for the fronts of functional areas such as

the company’s foyer, offices and showroom. As a quality

urban space, one hopes that it may favourably condition

the subsequent development of the industrial area.

But the building’s real gateway to the city, in functional,

visual and basically also symbolic terms, is the large indoor

rock-climbing gymnasium, the largest of its kind in Italy.

A block of variable heights to a maximum 19 metres, it has

an interior surface of 1,850 square metres on which ascents

of varying difficulties can be experienced, from a basic

level to that of expert sports competitions. This is already

a particularly popular place, due also to its views of the

landscape, with a front that can be opened at any time of

the year, even in tepid or cold winter or spring days, to give

climbers a direct contact with the exterior.

This building can, in a sense, be considered a unique work,

resulting from an active and conditioning process of

selection by the client, extending from the choice of place

(Bolzano) to the architects (through a two-phase ideas

competition by invitation, involving architects of the

calibre of Perrault, Bearth & Deplazes, Pichler, Mahlknecht

& Mutschlechner, Tscholl), and to the professionals,

managers and all the technicians (through bids for tender)

that led to the final definition of the complex functional

machine.

—

Luka Skansi

Architecture historian, iuav

53