Review

SARS-Coronavirus, an emerging pathogen:

what are the implications for the safety of blood transfusion?

Giancarlo Icardi(1), Filippo Ansaldi(2), Roberto Gasparini(3)

(1)

(2)

(3)

Department of Health Sciences, University of Genoa; Standing Group for the control of SARS - Ministry

of Health, subgroup on epidemiological scenarios

Department of Public Health, University of Trieste; Standing Group for the control of SARS - Ministry

of Health, subgroup on diagnosis and subgroup on SARS and blood donation

Department of Health Sciences, University of Genoa; Standing Group for the control of SARS - Ministry

of Health, subgroup on epidemiological surveillance

Emerging pathogens: from appearance

to epidemic risk

I patogeni emergenti: dalla comparsa

al rischio epidemico

In the last twenty-five years the epidemiological picture

of transmissible diseases has been characterised by the

appearance and identification of an ever increasing number

of micro-organisms. In particular, new viruses have

appeared in the human clade and have been recognised as

the cause of new diseases: the long list includes whole

families such as the Retroviridae whose members Human

T-cell Lymphotropic Virus type-1 (HTLV-I) and Human

Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) were discovered in 1980

and 1983, or viruses affecting the same target organ, such

as the major hepatotrophic viruses, including hepatitis C

virus, delta viroid and hepatitis E virus, identified at the

end of the 1980s and in the early years of the 1990s1.

Other viruses, such as the West Nile Virus and the

Monkeypox Virus, micro-organisms discovered decades

ago, have recently reappeared in epidemic form, raising

concern and alarm because of their rapid spread in

developed countries2-5.

The reasons for the increase in the so-called emerging

viruses are numerous and complex: the introduction and

spread of molecular techniques capable of identifying and

characterising the genome of micro-organisms with a high

degree of sensitivity and specificity have undoubtedly

played an important role, but it is equally clear that social,

ecological and epidemiological changes have led to

increased contact between men and animals and to faster

circulation of the micro-organisms. The demographic

Da cinque lustri il quadro epidemiologico delle malattie

trasmissibili è stato caratterizzato dall'introduzione e

dall'identificazione di un numero sempre maggiore di

microrganismi. In particolare, nuovi virus si sono affacciati

nel clade umano e sono stati riconosciuti causa di nuove

malattie: il lungo elenco comprende intere famiglie come

quella delle Retroviridae a cui appartengono l'Human Tcell Lymphotropic Virus type-1 (HTLV-I) e l'Human

Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), scoperti nel 1980 e 1983, o

virus caratterizzati dallo stesso organo bersaglio quali gli

epatotropi maggiori, che comprendono il virus dell'epatite

C, il viroide delta, il virus dell'epatite E individuati a cavallo

degli anni ottanta e novanta1. Negli ultimi mesi, altri virus,

quali il West Nile Virus ed il Monkeypox Virus,

microrganismi noti da decenni, sono ricomparsi in forma

epidemica destando allarme e preoccupazione per la loro

rapida diffusione in realtà socio-sanitarie sviluppate2-5.

Le ragioni dell'aumento dei cosiddetti virus emergenti

sono numerose e complesse: un ruolo di grande importanza

è stato sicuramente giocato dall'introduzione e dalla

diffusione di tecniche molecolari in grado di identificare e

caratterizzare con elevata sensibilità e specificità il genoma

dei microrganismi, ma è fuori di dubbio che i mutamenti

sociali, ecologici ed epidemiologici hanno determinato, da

un lato, un aumento dei contatti tra uomo e animale e,

dall'altro, una più rapida circolazione dei microrganismi.

L'esplosione demografica ha determinato aree del nostro

pianeta caratterizzate da una considerevole biodiversità e

da un'elevata densità abitativa, condizione in cui i contatti

tra uomo e animale e la trasmissione di microrganismi da un

clade all'altro possono essere più frequenti. Una regione

in cui questo fenomeno è particolarmente evidente è

Correspondence:

Prof. Giancarlo Icardi

Dipartimento di Scienze della Salute

Via Pastore 1

16132 Genova

Blood Transf 2003; 3: 215-23

215

G Icardi et al.

explosion has created areas of our planet with considerable

biodiversity and a high population density, conditions

facilitating contact between man and animals and the

transmission of micro-organisms from one clade to another.

One region in which this phenomenon is particularly evident

is South-East Asia. An outstanding example of the possible

interspecies movement of viruses in this area is the influenza

virus. It seems certain that influenza viruses circulating

among aquatic birds, the natural reservoir of the microorganism, have infected chicken, turkey, swine6, whales7

and have been responsible for epidemics among horses8.

Of more interest, as far as concerns possible consequences

for humans, is the transmission of avian viruses to pigs,

which could represent the mixing vessel between viruses

of avian origin and human viruses. In fact, pigs have some

particular features that make recombination of viral RNA

segments possible during co-infection with both avian and

human viruses, thus allowing the creation of new viruses9,10.

The influenza virus needs a glycoprotein receptor on the

target cell for the replication. This glucidic part of this

receptor terminates with a Sia2-3Gal bond for viruses of

the avian clade and a Sia2-6Gal bond for those of the human

clade. The target cells in pigs have both receptors, making

co-infection possible and also bringing the avian and

human viruses into very close proximity. In these

conditions, the characteristic organisation of the segmented

genome of the influenza virus allows a single gene of the

avian virus to be incorporated into the genome of the human

virus, thus causing recombination of the genetic material

of the micro-organism. This rearrangement between viruses

infecting different species seems to be responsible for the

major variations in the virus, named antigenic shift, and

seems to be implicated in the origin of the influenza

pandemics of the 20th century. The 1957 pandemic, the socalled "Asian flu", originated from the recombination of a

circulating avian H2N2 virus and a human H1N1 virus in

pigs; the resulting pandemic virus had 3 genes of avian

origin (HA, NA, PB1) and the remaining 5 of human origin.

This recombination, having involved the genes coding for

haemagglutinin and neuraminidase, the most important

antigenic determinants, created a virus to which the whole

population was susceptible and thus the conditions

necessary for perpetuation of the pandemic. The

mechanism underlying the appearance of the influenza virus

responsible for the 1968 pandemic, the so-called "Hong

Kong flu" was identical. Avian viruses were reported to

have infected humans directly in southern China in the

second half of the 1990s; in particular, in 1997 and 1999

there were cases of infection with H5N1 and H9N2,

respectively; the jump of the H5N1 virus from chickens,

216

rappresentata dal Sud-Est Asiatico. Un esempio eclatante

del possibile salto interspecie di un virus in quest'area è

espresso dall'influenza. Sembra, infatti, accertato che virus

influenzali circolanti negli uccelli acquatici, reservoir

naturale del microrganismo, abbiano infettato polli, tacchini,

suini6, balene7 e siano stati responsabili di epidemie negli

equini8. Di maggiore interesse, per quanto riguarda i possibili

effetti sull'uomo, è la trasmissione di virus aviari al maiale

che può rappresentare il mixing vessel tra virus di origine

aviaria e virus umani. Il maiale presenta, infatti, alcune

peculiarità che rendono possibile il riassortimento di

segmenti di RNA virale durante la coinfezione di virus aviari

e umani, permettendo la creazione di nuovi virus9,10. Il virus

influenzale necessita, a livello della cellula bersaglio, di un

recettore costituito da una glicoproteina, la cui parte

glucidica termina con un legame Sia2-3Gal per i virus del

clade aviario e Sia2-6Gal per i virus del clade umano. Le

cellule target dei suini presentano entrambi i recettori e

rendono così possibile la coinfezione e la stretta "vicinanza"

di virus aviari e umani. In queste condizioni, la caratteristica

organizzazione del genoma segmentato del virus influenzale

permette che un singolo gene del virus aviario possa essere

incorporato nel genoma di un virus umano, determinando

la ricombinazione del materiale genetico del microrganismo.

Questo meccanismo di riassortimento del materiale genetico

fra virus infettanti specie differenti sembra responsabile

delle cosiddette variazioni maggiori o antigenic shift e

sembra coinvolto nell'origine delle pandemie influenzali che

si sono verificate nel XX secolo. La pandemia del 1957, la

cosiddetta "asiatica", è stata originata dalla ricombinazione

nel suino di un virus aviario circolante H2N2 ed un virus

umano H1N1; il virus pandemico risultante possedeva un

corredo genetico caratterizzato da 3 geni di origine aviaria

(HA, NA, PB1) ed i restanti 5 umani. Il riassortimento,

avendo coinvolto i geni codificanti l'emoagglutinina e la

neuraminidasi, i determinanti antigenici di maggior rilievo,

ha determinato la comparsa di un virus verso cui l'intera

popolazione era suscettibile e ha creato, quindi, quelle

condizioni necessarie per il perpetrarsi della pandemia. Del

tutto analogo il meccanismo che ha determinato la comparsa

del virus influenzale responsabile della pandemia del 1968,

la cosiddetta "Honk Kong". Il salto interspecie diretto di

virus aviari nel clade umano è stato segnalato sempre

nell'area meridionale della Cina nella seconda metà degli

anni novanta; in particolare nel 1997 e 1999, si sono verificati,

rispettivamente, casi di infezione da H5N1 e H9N2; di rilievo

è stato il salto del virus H5N1 dal pollo, dove circolava in

forma epidemica, all'uomo con 18 malati fra gli addetti al

mercato di Honk Kong ed una letalità del 33%11,12.

La comparsa di nuovi patogeni, caratterizzati da una

Blood Transf 2003; 3: 215-23

SARS and blood transfusion

among which it circulated in endemic form, to humans,

infecting 18 market workers in Hong Kong, with a mortality

rate of 33%, was noteworthy11,12.

The appearance of new pathogens with a viraemic

phase, which are potentially transmissible parenterally, is a

problem for transfusion medicine. The rest of this review is

dedicated to the description of a new virus responsible for

an epidemic of atypical pneumonia which has involved

numerous countries in Asia, America and Europe. The main

structural features of the virus are analysed and the current

diagnostic instruments indicated. Finally, the possible risk

of transfusion-related transmission of the new microorganism is considered.

st

The first epidemic of the 21 century

Although the first official notification of an epidemic of

atypical pneumonia was made on February 11th, 2003, the

first cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS)

can be traced back to mid-November 2002 in the province

of Guangdong in South China. In the period between the

index case and notification to the World Health Organisation

(WHO), 305 people had fallen ill and 5 had died of the

syndrome. About 30% of the people infected were health

care workers who had come into close contact with the sick

patients. On February 21st, a Chinese doctor who worked in

an out-patients department in the region of Guangdong

moved to Hong Kong and rented a room on the ninth floor

of a hotel in the centre of the city. Over the next few days at

least 12 of the hotel's guests developed early symptoms of

SARS: some of these people were admitted to the Queen

Mary Hospital and to the Prince of Wales Hospital in Hong

Kong, while others continued their journeys and were

admitted to hospitals in Hanoi (Vietnam), Toronto (Canada)

and Singapore13,14. The number of cases multiplied rapidly,

particularly among health care workers in close contact with

patients, and the syndrome spread, carried by international

travellers. New cases of infection were reported in Hong

Kong, Singapore, Canada and China. On March 12th, the

WHO issued a Global Alert and on March 15th, the

Emergency Travel Advisory. The cumulative number of

cases reported exceeded 5,000 on April 28th, 6,000 on May

2nd and 7,000 on May 8th; 30 countries in 6 continents were

involved by the epidemic. The peak of the epidemic was

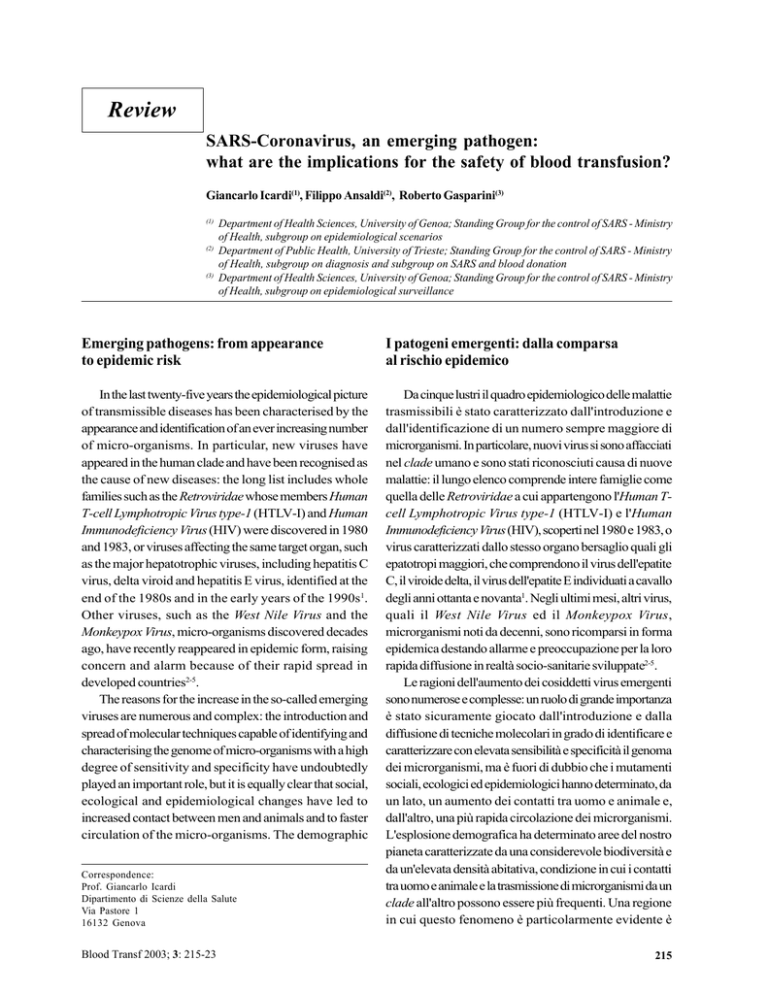

reached in the first week of May (Figure 1), during which

1,400 cases were reported. In the following weeks the number

of cases decreased rapidly although there were some alarming

new outbreaks in continental China, Taiwan and Canada

after the epidemic had apparently been controlled. In the

Blood Transf 2003; 3: 215-23

fase viremica e potenzialmente in grado di trasmissione

parenterale, rappresenta una potenziale problematica di

medicina trasfusionale. Di seguito verrà descritta la

comparsa di un nuovo virus responsabile di un'epidemia di

polmonite atipica che ha coinvolto numerosi Paesi dell'Asia,

dell'America e dell'Europa. Verranno, poi, analizzate le

principali caratteristiche strutturali e saranno indicati gli

attuali strumenti diagnostici e, infine, sarà valutato il

possibile rischio trasfusionale legato alla trasmissione del

nuovo microrganismo.

La prima epidemia del XXI secolo

Sebbene la prima segnalazione ufficiale di un'epidemia

di polmonite atipica risalga all'11 febbraio 2003, i primi casi

di Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) si possono

far risalire alla metà del novembre 2002 nella provincia di

Guangdong nella Cina Meridionale. Nel periodo intercorso

tra la comparsa del caso indice e la segnalazione

all'Organizzazione Mondiale della Sanità (OMS), 305

soggetti si erano ammalati e 5 erano morti per la sindrome.

Circa il 30% degli infetti erano operatori sanitari, venuti a

stretto contatto con i malati. Un medico cinese che operava

in un ambulatorio nella regione di Guangdong si trasferisce,

il 21 Febbraio, ad Honk Kong e si stabilisce al nono piano

di un albergo del centro cittadino. Nei giorni successivi

almeno 12 ospiti dell'albergo manifestano i primi sintomi:

alcuni di essi vengono ricoverati al Queen Mary Hospital e

Prince of Wales Hospital di Honk Kong, altri, raggiungono

le successive tappe del loro viaggio e vengono

ospedalizzati ad Hanoi (Vietnam), Toronto (Canada) e

Singapore13,14. Rapidamente, i casi si moltiplicano

soprattutto negli operatori sanitari venuti a stretto contatto

con i malati e la sindrome si diffonde, veicolata dai

viaggiatori internazionali. Nuovi infetti vengono segnalati

ad Honk Kong, Singapore, Canada, Cina. Il 12 marzo, l'OMS

lancia la Global Alert ed il 15 marzo l'Emegency Travel

Advisory. Il numero cumulativo di casi registrati supera le

5.000 unità il 28 aprile, le 6.000 il 2 maggio, le 7.000 l'8 maggio,

con 30 nazioni in 6 continenti coinvolti dall'epidemia. Il

picco epidemico viene raggiunto la prima settimana di

maggio (Figura 1), con 1.400 casi riportati. Nelle settimane

successive, si è osservata una rapida diminuzione dei casi,

con alcune preoccupanti eccezioni rappresentate dalla Cina

continentale, da Taiwan e dal Canada, dove, dopo una fase

di controllo dell'infezione, si è assistito ad una

recrudescenza dell'epidemia. Nell'ultima settimana di giugno,

Pechino ed Hong Kong, due delle città più colpite

dall'epidemia, sono state dichiarate libere da trasmissione

217

G Icardi et al.

Figure 1 - Course of SARS epidemic (source: www.who.int)

last week of June, Peking and Hong Kong, two of the cities

most severely affected by the epidemic, were declared free

of local transmission and new cases were recorded only in

Toronto and Taiwan.

At the time of writing (September 2003), 8,098 cases

have been reported and the mortality rate, calculated by

the WHO, is 10%, although it reaches almost 50% in over

65-year olds.

Identification of the causal agent: the SARS-CoV

Since April 2000, the WHO has co-ordinated the Global

Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN), an

international network fed by 112 other national or

continental networks, which collects virological,

bacteriological and epidemiological surveillance data and

unites the expertise of the international scientific community

in order to guarantee a rapid response in the case of the

risk of an epidemic. Since its creation in 1998, up to 2002,

over 500 epidemic events had been investigated in 132

countries, but rarely has GOARN and its partner networks

been required so urgently. The initial plan of intervention

was decided between March 12th and 15th and was based

on the creation of a network of 11 laboratories given the

task of identifying the agent causing SARS. On April 17th,

just one month after the constitution of the network of

laboratories, it was announced that the aetiological agent

had been identified: a new virus belonging to the

Coronavirus family15,16. A few days later, the complete

sequence of the genome of the new micro-organism was

published online in the World Wide Web.

The SARS-CoV, as the new virus was called, although

218

locale e solamente a Toronto e Taiwan vengono registrati

nuovi casi.

A tutt'oggi (settembre 2003), sono stati riportati 8.098

casi e la letalità, calcolata dall'OMS, è pari al 10%, con punte

fino al 50% nella popolazione ultrasessantacinquenne.

L'identificazione dell'agente causale: il SARS-CoV

Dall'aprile 2000, l'OMS coordina il Global Outbreak

Alert and Response Network (GOARN), una rete

internazionale, cui afferiscono altri 112 network nazionali o

continentali, in grado di raccogliere dati di sorveglianza

epidemiologica, batteriologica e virologica, e di riunire

l'epertise della comunità scientifica internazionale per

garantire una risposta rapida in caso di rischio epidemico.

Dalla fondazione nel 1998 al 2002, oltre 500 eventi epidemici

sono stati investigati in 132 Paesi, ma in poche altre

situazioni la richiesta al GOARN e ai network partner è

stata così urgente. Il piano iniziale d'intervento è stato

progettato tra il 12 ed il 15 marzo e ha visto tra i suoi punti

caratterizzanti la creazione di una rete di 11 laboratori volta

all'identificazione dell'agente causale della SARS. Il 17 aprile,

a un mese dalla costituzione del network di laboratori, viene

dato l'annuncio dell'identificazione dell'agente etiologico:

un nuovo virus appartenente alla famiglia dei

Coronavirus15,16. Alcuni giorni dopo, viene pubblicata in

rete la sequenza completa del genoma del nuovo

microrganismo.

Il SARS-CoV, come viene battezzato il nuovo virus, pur

mantenendone la struttura, è filogeneticamente lontano dai

Coronavirus isolati nell'uomo e negli altri animali e va a

costituire un cluster ben separato dagli altri tre in cui erano

Blood Transf 2003; 3: 215-23

SARS and blood transfusion

maintaining the structure of a Coronavirus, is

phylogenetically distant from the Coronaviruses isolated

in man and other animals and forms a cluster clearly distinct

from the other three in which the micro-organisms of this

family had so far been grouped17,18. Many hypotheses on

the origin of the SARS-CoV have been offered, but most

are subject of ongoing studies and only preliminary results

are available. Sequencing analysis has shown that the open

reading frames, coding for the structural and non-structural

proteins of the virus, do not resemble those of the other

Coronaviruses, which indicates that recombination

phenomena with already known viruses are improbable,

despite the fact that genetic exchange between microorganisms of this family are common and have been well

documented in the literature17-19. The new micro-organism

seems to have evolved independently, but the host in which

it accumulated its numerous mutations remains to be

discovered. This information is of fundamental importance,

not only for the phylogenetic analysis and identification of

the evolutionary mechanisms of the new micro-organism,

but above all to discover the natural reservoir, to predict

antigenic variation and therefore to be able to fine-tune the

preventive and diagnostic instruments. Preliminary studies,

presented at the recent Expert Meetings held in Kuala

Lumpur in the third week of June and in Okinawa, Japan, in

October, revealed that viruses similar to SARS-CoV have

been isolated from the Himalayan palm civet and Raccoondog, two small mammals whose natural habitat is southern

China20. Neither chicken nor pigs, key animals in the antigenic

shift of influenza viruses, seem to play and important role in

the evolution of SARS-CoV and do not seem to provide a

viral reservoir21.

The diagnostic approach and transfusion risk

The possibility of an early diagnosis and identification

of the most appropriate diagnostic instrument are

inseparably linked to physiological knowledge and

understanding of the natural history of the infection. The

lack of information about the anatomical sites and duration

of replication of SARS-CoV, the viral load in biological

fluids during the various stages of the infection and the

resistance of the micro-organism outside the host, are all

obstacles to producing diagnostic strategies. Indeed,

some aspects of the kinetics of the virus have surprised

the scientific community: unlike other viruses that

replicate in mucosa (such as the influenza orthomyxovirus)

or have air-borne transmission and double replication

(such as the measles paramyxovirus), SARS-CoV is not

Blood Transf 2003; 3: 215-23

fino ad oggi raggruppati i microrganismi di questa

famiglia17,18. Sull'origine del SARS-CoV sono state proposte

molte ipotesi, ma gran parte degli studi sono in progress e

solo i primi risultati sono disponibili. L'analisi di sequenza

ha rivelato che gli open reading frame, codificanti le

proteine strutturali e non strutturali del virus, sono distanti

da quelli degli altri Coronavirus, il che sta a indicare che

fenomeni di ricombinazione con virus ad oggi noti sono

improbabili, nonostante lo scambio genetico fra

microrganismi di questa famiglia sia frequente e ben

documentato in letteratura17-19. Il nuovo microrganismo

sembra si sia evoluto in modo indipendente, ma rimane da

scoprire in quale ospite abbia accumulato le numerose

mutazioni. Questi dati hanno un ruolo fondamentale, non

solo per l'analisi filogenetica e l'individuazione dei

meccanismi evolutivi del nuovo microrganismo, ma sono

di grande importanza per individuarne il reservoir naturale,

predirne la variazione antigenica e calibrare, quindi, gli

strumenti preventivi e diagnostici. Studi preliminari,

presentati ai recenti Expert Meetings, svoltosi a Kuala

Lumpur nella terza settimana di giugno e a Okinawa in

ottobre, hanno rivelato come virus simili al SARS-CoV siano

stati isolati nell'Himalayan palm civet e nel Raccon-dog,

due piccoli mammiferi che hanno il loro habitat nella Cina

meridionale20. Sia polli che suini, animali-chiave nello shift

dei virus influenzali, non sembrano giocare un ruolo

importante nell'evoluzione del SARS-CoV e non sembrano

rappresentare il reservoir virale21.

L'approccio diagnostico e il rischio trasfusionale

La possibilità di una diagnosi precoce e l'identificazione

dello strumento diagnostico più idoneo non possono

prescindere dalle conoscenze sulla fisiopatologia e sulla

storia naturale dell'infezione. Le lacune che ancora esistono

sui siti anatomici e sulla durata della replicazione del SARSCoV, sulla concentrazione virale nei liquidi biologici durante

le diverse fasi dell'infezione e la resistenza del microrganismo

al di fuori dell'ospite, rappresentano ostacoli per la messa a

punto di strategie diagnostiche. In particolare, alcuni aspetti

riguardo la cinetica virale hanno sorpreso la comunità

scientifica: contrariamente ad altri virus a replicazione

mucosale (quale l'orthomixovirus dell'influenza) o

caratterizzati da trasmissione aerea e duplice replicazione

(quali il paramyxovirus del morbillo), il SARS-CoV non è

eliminato in modo massivo nell'ultima fase dell'incubazione

e nei primi giorni dalla comparsa dei sintomi. I primi studi di

cinetica virale hanno permesso di rilevare il massimo

shedding intorno al 10°-12° giorno dalla comparsa dei

219

G Icardi et al.

massively eliminated in the final phase of the incubation

and during the first few days of symptoms. The early

studies of the viral kinetics revealed that maximum

shedding occurs between the 10th - 12th day after the onset

of symptoms. This fact obviously affects the detection

rate of the virus in the faeces and nasopharyngeal

aspirates, which are the substrates in which non-SARS

human Coronaviruses are eliminated. Preliminary data on

Hong Kong patients, presented by JSM Peiris at the Kuala

Lumpur conference, 22 showed that 25-45% of

nasopharyngeal swabs were positive in the first week

and 65-80% in the second week after the onset of the

symptoms22,23. The SARS-CoV was detected later in faecal

samples: in fact, it was completely absent up to the 5th-6th

day, but was found in 85% of samples between the 11th

and 16th day.

The low viral shedding in the first week following the

onset of symptoms leads to the need to produce highly

sensitive diagnostic techniques to guarantee the early

diagnosis, essential for prevention. The approaches so

far used for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV are the classical

virology methods based on direct detection of the virus

by isolation from cell cultures or molecular techniques or

detection of specific immunofluorescent antibodies. The

most promising, in terms of fast performance and high

sensitivity, are the tests based on gene amplification. The

sequencing information on the first isolates allowed the

design of primers, already available on April 17th, and

the development of nested-PCR and real-time PCR. The

need to have a sensitive and specific test as quickly as

possible spurred the effort to standardise the proposed

tests, but the process of optimisation has only just begun.

At present, the laboratory tests are only an important

complement to a diagnosis still based on clinical and

epidemiological data. In fact, following the latest WHO

indications, negative results in current diagnostic tests

do not have particular relevance for the management of a

possible SARS-CoV infection or for undertaking control

measures. The reasons for the poor predictive value of a

negative test lies in the very low viral shedding in the

first stage of the infection, in the insufficiently low

sensitivity of the PCR-based tests and in the delayed

appearance of the antibodies. The diagnostic tests must

still overcome many of these problems. The variability

and evolutionary capacity of the virus are still largely

unknown and the first studies highlight mutations in

regions that, until now, had been considered highly

conserved24. If this finding is also confirmed for the region

amplified in molecular tests, it would make current

techniques less sensitive and increase the number of false

220

sintomi. Questo dato ha naturalmente influenzato la

percentuale di rilevamento del virus nelle feci e nell'aspirato

naso-faringeo, che rappresentano i substrati in cui vengono

eliminati i Coronavirus umani non-SARS. Dati preliminari

presentati alla Conferenza di Kuala Lumpur da JSM Peiris22

sui pazienti di Hong Kong hanno mostrato positività del

25-45% dei tamponi naso-faringei nella prima settimana e

65-80% nella seconda settimana dalla comparsa dei

sintomi22,23. Il SARS-CoV è stato rilevato più tardivamente

nei campioni di feci: è risultato, infatti, completamente

assente fino al 5°-6° giorno per raggiungere la percentuale

di positivi dell'85% tra l'11° e il 16° giorno. Il basso shedding

virale nella prima settimana dalla comparsa dei sintomi

spinge alla necessità di tecniche ad elevata sensibilità al

fine di garantire una diagnosi precoce, indispensabile a fini

preventivi. Gli approcci fino ad ora impiegati per la

diagnostica del SARS-CoV sono quelli classici della

virologia e si basano sul rilevamento diretto del virus,

mediante isolamento su coltura cellulare o tecniche

molecolari o la rivelazione degli anticorpi specifici in

immunofluorescenza. Sicuramente più promettenti, per

velocità di esecuzione ed elevata sensibilità, sono i test

basati sull'amplificazione di materiale genetico. Le

informazioni sulla sequenza dei primi isolati hanno permesso

il disegno dei primers, la cui sequenza era disponibile già il

17 aprile, e la messa a punto di nested-PCR e real-time

PCR. La necessità della disponibilità al più presto di un

test sensibile e specifico ha moltiplicato gli sforzi per la

standardizzazione dei test proposti, ma il processo di

ottimizzazione è, con ogni probabilità, appena incominciato.

Attualmente, i test di laboratorio rappresentano soltanto

un importante complemento alla diagnosi, che rimane legata

a criteri clinici ed epidemiologici. Il risultato negativo agli

attuali test diagnostici non assume, infatti, seguendo le

indicazione dell'OMS e da quanto emerso dalle più recenti

revisioni, particolare significato nella gestione della

possibile infezione da SARS-CoV e nell'intraprendere le

misure di controllo. Le ragioni dello scarso valore predittivo

del test negativo vanno ricercate nello shedding virale

molto basso nella prima fase di infezione, in una sensibilità

troppo bassa dei PCR-based test e nella comparsa tardiva

degli anticorpi. Molti sono i quesiti ancora aperti e le

problematiche da affrontare in ambito diagnostico. La

variabilità e la capacità evolutiva del virus sono ancora

largamente sconosciute e i primi studi mettono un luce

mutazioni in regioni fino ad oggi ritenute molto

conservate24. Queste informazioni, se confermate per la

regione amplificata dai test molecolari, potrebbero rendere

meno sensibili le attuali tecniche ed aumentare il numero

dei falsi negativi. Inoltre, non è di facile interpretazione, sia

Blood Transf 2003; 3: 215-23

SARS and blood transfusion

negatives. Furthermore, it is not easy give a diagnostic or

epidemiological interpretation to the finding of a modest

amount of viral RNA in asymptomatic individuals or in

patients with very few symptoms25.

The finding of viral RNA, albeit in limited amounts, in

the plasma of patients in the acute phase of the disease,

raises the spectre of the risk of transmission of SARSCoV via blood or blood products26. So far, no case of

probable SARS has been attributed to this route of

transmission but, given the theoretical risk, the

Department of Blood Safety and Clinical Technology of

the WHO has issued a series of recommendations. The

recommendations for those areas, such as Italy, in which

local transmission has not occurred, electively concern

travellers arriving from infected areas. Asymptomatic

travellers should delay donation until 3 weeks after their

return; symptomatic travellers who are defined as

suspected or probable cases should delay donation for,

respectively, one or three months after the completion of

treatment and the disappearance of symptoms. These

recommendations are also valid in areas of recent local

transmission: a person in close contact with a case should

delay donation for 3 weeks, while suspected and

probable cases are subject to the same recommendations

described above (www.who.int/csr/sars). While awaiting

a highly sensitive diagnostic test for the detection of

Coronavirus in the blood and an evaluation of the

appropriateness of introducing this into blood testing,

donor selection plays an essential role. The numerous

uncertainties concerning the natural history of the

infection are reflected by the questions on the possible

role of transfusion as a method of transmission of SARSCoV. The risk assessment associated with transfusion

of blood components and plasma derivatives, which can

be defined by look back and trace back studies, presymptomatic viraemia, ex vivo stability of the virus,

protocols for the production of blood components, as

well as the use of convalescents are the current priorities

in Transfusion Medicine research26,27.

Blood Transf 2003; 3: 215-23

dal punto di vista diagnostico che epidemiologico, il

rilevamento di modeste quantità di RNA virale in soggetti

asintomatici o paucisintomatici25.

Il rilievo di RNA virale nel plasma di pazienti in fase

acuta, seppure in quantità modeste, ha proposto

all'attenzione della comunità scientifica il rischio della

trasmissione del SARS-CoV mediante sangue o

emoderivati26. A oggi, nessun caso probabile di SARS è

ascrivibile a questa modalità di trasmissione, ma in funzione

di questo rischio teorico il Department of Blood Safety

and Clinical Technology dell'OMS ha proposto una serie

di raccomandazioni. Le raccomandazioni per quelle aree,

come l'Italia, in cui non si è verificata trasmissione locale,

riguardano elettivamente i viaggiatori provenienti da aree

infette. I viaggiatori asintomatici dovranno posticipare la

donazione di 3 settimane dalla data del ritorno, i viaggiatori

sintomatici che rientrano nella definizione di caso sospetto

o probabile dovranno posticipare la donazione,

rispettivamente, di 1 mese o 3 mesi dalla cessazione della

terapia e dal termine della sintomatologia. Queste

raccomandazioni vengono riprese anche in quadri

epidemiologici caratterizzati da recente trasmissione locale:

il contatto stretto di caso dovrà posticipare la donazione di

3 settimane, mentre per i casi sospetti o probabili valgono

le indicazioni soprariportate (www.who.int/csr/sars). In

attesa di un test diagnostico ad elevata sensibilità per il

rilevamento del Coronavirus nel sangue e della valutazione

sull'opportunità dell'introduzione di un test di questo tipo

nel blood testing, la selezione del donatore gioca il ruolo

principale. Le numerose incertezze sulla storia naturale

dell'infezione si riflettono sugli interrogativi sul possibile

ruolo della trasfusione quale modalità di trasmissione del

SARS-CoV. Il risk assessment, legato alla trasfusione di

sangue di emocomponenti e di plasmaderivati, definibile

con studi look back and trace back, la viremia presintomatica, la stabilità del virus ex vivo, la valutazione del

rischio nei plasmaderivati e i protocolli per la loro

produzione, nonché l'uso dei convalescenti sono

attualmente quesiti prioritari per la ricerca in ambito

trasfusionale26,27.

221

G Icardi et al.

References

1) Woolhouse MEJ. Population biology of emerging and re-emerging pathogens. Trends in Microbiol 2002; 10: S3-S7.

2) Leport C, Janowski M, Brun-Vezinet F, et al. West Nile virus meningomyeloencephalitis—value of interferon assays in primary

encephalitis. Ann Med Intern 1984; 135: 460-3.

3) Han LL, Popovici F, Alexander JP Jr, et al. Risk factors for West Nile virus infection and meningoencephalitis, Romania,1996. J

Infect Dis 1999; 179: 230-3.

4) Mukinda VB, Mwema G, Kilundu M, et al. Re-emergence of human monkeypox in Zaire in 1996. Monkeypox Epidemiologic

Working Group. Lancet 1997; 349: 1449-50.

5) CDC. Multistate outbreak of monkeypox-Illinois, Indiana, and Wisconsin, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003; 52:

537-40.

6) Scholtissek C, Burger H, Bachman PA, Hannoun C. Genetic relatedness of haemaggglutinins of the H1 subtype of influenza A

viruses isolated from swine and birds. Virology 1983; 129: 521-3.

7) Hinshaw VS, Webster RG, Turner B. Novel influenza A viruses isolated from Canadian feral ducks: including strain antigenically

related to swine influenza (Hsw1N1) viruses. J Gen Virol 1978; 41: 115-27.

8) Guo Y, Wang M, Kawaosoka Y, et al. Characterization of a new avian-like influenza A viruses from horses in China. Virology 1992;

188: 245-55.

9) Scholtissek C, Burger H, Kistner O, Shortridge KF. The nucleoprotein as a possible major factor in determining host specificity

of influenza H3N2 viruses. Virology 1985; 147: 287-94.

10) Scholtissek C. Pigs as "mixing vessels" for the creation of new pandemic influenza A viruses. Med Principles Pract 1990; 2: 6571.

11) Chan PK. Outbreak of avian influenza A(H5N1) virus infection in Hong Kong in 1997. Clin Infect Dis 2002; 34: S58-64.

12) Lin YP, Shaw M, Gregory V, et al. Avian-to-human transmission of H9N2 subtype influenza A viruses: relationship between

H9N2 and H5N1 human isolates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000; 97: 9654-8.

13) Tsang KW, Ho PL, Ooi G, et al. A cluster of cases of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in Hong Kong. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:

1977-85.

14) Poutanen SM, Low DE, Henry B, et al. Identification of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in Canada. N Engl J Med 2003; 348:

1995-2005.

15) Ksiatek TG, Erdman D, Gordsmith C, et al. A novel Coronavirus associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. N Engl

J Med 2003; 348: 1947-58.

16) Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W, et al. Identification of a novel Coronavirus in patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome.

N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 1667-76.

17) Marra MA, Jones SJM, Astell CR, et al. The genome sequence of the SARS-associated Coronavirus. Science 2003; 300: 1399404.

18) Rota PA, Oberste MS, Monroe SS, et al. Characterization of a novel Coronavirus associated with Severe Acute Respiratory

Syndrome. Science 2003; 300: 1394-9.

19) Lai MMC. RNA recombination in animal and plant viruses. Microbiol Rev 1992; 56: 61-79.

20) Guan Y, Zheng BJ, Shortridge KF, et al. Isolation and characterization of viruses related to SARS Coronavirus from animals in

Southern China. Personal Communication in WHO Global Conference on Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Kuala Lumpur,

Malaysia, 17-18 June 2003.

21) Weirgartl H, Copps J, Drebot M, et al. Susceptibility of pigs and chickens to SARS Coronavirus. Personal Communication in

WHO Global Conference on Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17-18 June 2003.

22) Peiris JSM. SARS: aetiology. Personal Communication in WHO Global Conference on Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome.

Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17-18 June 2003.

23) Peiris JSM, Chu CM, Cheng VCC, et al. Clinical progression and viral load in a community outbreak of Coronavirus associated

SARS pneumonia: a prospective study. Lancet 2003; 361: 1767-71.

24) Ruan YJ, Wei CL, Ee AL, et al. Comparative full-length genome sequence analysis of 14 SARS Coronavirus isolates and common

mutations associated with putative origins of infection. Lancet 2003; 361: 1779-86.

222

Blood Transf 2003; 3: 215-23

SARS and blood transfusion

25) WHO SARS Team. SARS laboratory diagnosis. Personal Communication in WHO Global Conference on Severe Acute Respiratory

Syndrome. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17-18 June 2003.

26) Dhingra N. SARS as an emerging pathogen: implications for blood safety. Personal Communication in WHO Global Conference

on Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17-18 June 2003.

27) Lloyd N. Blood safety – WHO strategies. Personal Communication in: The impact of SARS and other emerging pathogens on

transfusion medicine. Brussels, Belgium, 16 June 2003.

Blood Transf 2003; 3: 215-23

223