SPEAK ENGLISH!

MAGAZINE

NO.41 – JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2016

IN THIS NUMBER:

FIRST PAGE: HOW TO

MAKE REAL FRIENDS

ENGLISH GRAMMAR:

TIME CLAUSES AND THE

PASSIVE

LET'S LAUGH

TOGETHER: JOKES

ABOUT STUDENTS

1

First Page

LIVELLO A2

HOW TO MAKE REAL FRIENDS

Thanks to1 technology, you can connect more2 conveniently with more people than3 at any4

other time in history. But sometimes the friends you have can seem not really good friends.

One young man says: “I feel as if my friends could leave me suddenly5. but my dad has

had the same friends for years!”. Why is it such a challenge6 these days to have durable

and meaningful7 friendships8?

WHAT YOU SHOULD KNOW

Technology can be part of the problem. Texting, social networking, and other social

media have made it seem possible to maintain a friendship without9 being in someone’s

presence. Meaningful conversations have been replaced10 by rapid texts and tweets. “Now

people have less11 real interactions,” says the book Artificial Maturity. “Students spend

more time in front of a screen12 and less time with each other13.”

In some cases, technology can make friendships seem closer14 than they really are. A boy

texted a lot of friends. He wanted to know if his friends were really interested in him and

stopped texting them. Only some friends texted him to know how he was. He understood

that he only had few15 good friends, the others weren't real friends.

But the problem isn't social media: they can, in fact, really help you to be in contact with

your real friends, but only if you also have a relation with them out of the social media.

WHAT YOU CAN DO

Who is a real friend. The Bible describes a friend as someone16 who “is closer than a

brother.” (Proverbs 18:24) Probably you want this kind17 of friends. But are YOU this kind

of friend? To answer the questions, write three qualities that you want in a friend. Then

write three qualities that YOU have. Ask yourself18: ‘Which of my online “friends” have the

qualities that I want in a friend? Can my friends say that I have these qualities?”

What is more important. Online friendships are often based on an interest in common,

for example a hobby or a sport. But if you have VALUES19 in common it is more important.

A girl says that she doesn't have a lot of friends, but the friends that she has help her to be

a better person.

Go out and meet people. There is nothing similar to face-to-face conversation, where you

and another person can observe the voice tone, facial expression, and body language.

Remember! Real friendship involves20 more than just staying in touch21. It requires that

you and your friend display22 love, empathy, patience, and forgiveness23. Those qualities

make a friendship rewarding24. But they are difficult to display when you only talk online.

VOCABULARY

1 thanks to: grazie a

7 meaningful: significativo 13 each other: l'un l'altro

19 value: valore

2 more: più

8 friendship: amicizia

14 closer: più intimo

20 to involve: implicare

3 than: di

9 without: senza

15 few: pochi

21 to stay in touch: rimanere in contatto

4 any: qualsiasi

10 replaced: sostituito

16 someone: qualcuno

22 to display: mostrare

5 suddenly: improvvisamente 11 less: meno

17 kind: tipo

23 forgiveness: perdono

6 challenge: sfida

12 screen: schermo

18 yourself: te stesso

24 rewarding: appagante

2

MONUMENTS OF BRITAIN

LIVELLI A2-B1

THE GOLDEN HIND

The Golden Hind (cerva d'oro) was an English galleon famous for her (NOTA: in inglese le

imbarcazioni sono sempre femminili) circumnavigation of the globe between 1577 and 1580,

captained bySir Francis Drake. She was the flagship1 of an expedition of five ships, and was the

only one to come back to England. The patron of the expedition was Sir Christopher Hatton,

whose2 coat of arms3 had a golden female

deer4 (also known as a ‘hinde’). The ship

had a golden hinde at her bow5, and that is

why she was called “Golden Hinde”.

In 1577, Queen Elizabeth chose Sir Francis

Drake as the leader of an expedition

intended to pass around South America

through6 the Strait of Magellan and to

explore the coast that lay beyond7. The

queen's support was advantageous; Drake

had official approval to take advantage of

the cargo8 stolen9 from the ships, with the

agreement10 that the Queen would have a

part of the treasure. Also, the queen gave

her explicit approval to cause the maximum

damage11 to the Spaniards. Queen Elizabeth,

however, couldn't give Drake an official

support to act12 as a pirate, so Drake

officially acted as a privateer13.

During the Anglo–Spanish War, Drake took

1 The copy of the Golden Hinde in the town of Brixham

also part in the battles against the Spanish

Invincible Armada on board the Golden

Hinde.

THE JOURNEY

Francis Drake set sail14 from Plymouth on 13th December 1577 with a fleet of 5 ships: the Pelican,

the Elizabeth, theMarigold, the Swan, and the Christopher(also known as the Benedict).

His mission was to open trade links15 with new nations and discover16 new shipping17 routes18, so as

to19 weaken20 the Spanish dominance of South America. He did this successfully, acquiring treasure

from Spanish ships and claiming21 land on behalf of22 Queen Elizabeth I.

3

In June 1578, he landed23 at Port San Julian, in modern day Argentina. It was here that fellow24

officer and friend, Thomas Doughty, was executed after a trial25 for mutiny26 and sedition.

At the Strait of Magellan, the Pelican was renamed27 the “Golden Hinde“

The Golden Hinde, the Elizabeth and the Marigold then sailed through the Strait of Magellan and

emerged in the Pacific Ocean.

A series of storms28 erupted, and the Marigold sank29 with all its cargo and the Elizabeth sailed back

to England. The Golden Hinde was blown30 to the southernmost31 point of South America, reaching

the island now known as Cape Horn (Capo Horn).

Francis Drake then sailed north along the west coast of South America acquiring treasure from

Spanish and Portuguese ships and settlements32. When he learned33 that the Spanish ship Nuestra

Senora de la Concepcion (Cacafuego) was sailing towards34 Peru laden35 with silver and jewels,

Drake quickly strove36 to make an interception.

The Golden Hinde caught up with the Cacafuego on 1st March 1579 off the coast of Mexico and

acquired 362,000 pesos worth37 of silver from the ship.

Francis Drake continued north and landed in North America, where he repaired the Golden Hinde.

He traded38 with the local Native Americans there, becoming the first European to make contact

with them.

He named the land ‘Nova Albion’ (New England), and claimed it in the name of Queen Elizabeth I.

Some historians believe it was located at Point Reyes, California.

Leaving North America, Drake sailed across the Pacific Ocean and through Asia. He arrived in

Plymouth via the Cape of Good Hope on 26th September 1580 – making him the first Englishman

to circumnavigate the world.

His treasure was calculated at £600,000 in Elizabethan money – many millions of today's pounds.

Queen Elizabeth I knighted39 Drake on 4th April 1581 aboard the Golden Hinde in Deptford,

declaring the ship should be a maritime museum.

Unfortunately, the ship disintegrated after about seventy years.

All that remains of the original Golden Hinde are a chair, which currently resides at the Bodleian

Library in Oxford, and a table named the ‘cupboard’ at the Middle Temple in London. However, a

copy af the Golden Hinde can still be admired today in the city of London or in the town of

Brixham, in Devon.

VOCABULARY

1 flagship: ammiaraglia

2 whose: il cui

3 coat of arms: stemma

4 deer: cervo

5 bow: prua

6 through: attraverso

7 to lie beyond: stare oltre

8 cargo: carico

9 stolen: rubato

10 agreement: accordo

4

11 damage: danno

21 to claim: rivendicare

12 to act: agire

22 on behalf of: per conto di

13 privateer: nave corsara 23 ro land: attraccare

14 to set sail: salpare

24 fellow: compagno

15 trade links: contatti commerciali 25 trial: processo

16 to discover: scoprire 26 mutiny: ammutinamento

17 dhipping: spedizione 27 to rename: ribattezzare

18 route: via

28 storm: tempesta

19 so as to: così da

29 to sink: affondare

20 to weaken: indebolire 30 blown: spinto (dal vento)

31 southernmos: più meridionale

32 settlement: insediamento

33 to learn: apprendere

34 towards: verso

35 laden: carico

36 to strive: lottare

37 worth: di valore

38 to trade: commerciare

39 to knight: far cavaliere

ENGLISH GRAMMAR

MUST, HAVE TO E SHOULD

MUST significa “dovere”, nel senso di “obbligo di fare”. Esempi:

–

I'm too tired, I must rest (sono troppo stanco, devo riposare)

–

when the traffic lights are red you must stop (quando il semaforo è rosso devi fermarti)

–

you must go home, it's becoming late (devi andare a casa, si sta facendo tardi)

MUST è uguale per tutte le persone: I-you-he-she-it-we-they must. La sua negativa è MUSTN'T,

contrazione di MUST NOT. La forma interrogativa, per quanto abbastanza rara, è MUST I-you-hewh-it-we-they …..?

NOTA: COME TUTTI GLI AUSILIARI, MUST E' SEMPRE SEGUITO DA UN VERBO

ALL'INFINITO SENZA TO (I must go, NON I must to go)

HAVE TO traduce la nostra espressione italiana “avere da” (per esempio “ho da fare”, “ho da

andare a fare la spesa”, “ho da comprare una nuova macchina prima possibile”), e indica sempre

una necessità. L'espressione inglese HAVE TO è comunque molto più usata rispetto alla nostra

espressione italiana AVERE DA, che generalmente è usata solo alla prima persona singolare IO o

alla seconda persona singolare TU.

Molto spesso non c'è molta differenza tra MUST e HAVE TO, perché solo io so se sento una data

cosa più come un obbligo o più come una necessità: la linea di confine tra un obbligo e una

necessità è molto sottile, cosicché il nostro verbo modale “DOVERE” in inglese si può tradurre

indifferentemente con entrambe le forme. Pertanto si può dire:

–

I must get up at 6 o'clock

o

I have to get up at 6 o'clock

–

you must do your homework

o

you have to do your homework

–

we must work to live

o

we have to work to live

La principale differenza è che HAVE TO non è un verbo modale, e quindi alla terza persona diventa

HAS TO, fa la negativa utilizzando gli ausiliari DON'T e DOESN'T, e la forma interrogativa

utilizzando DO e DOES.

MA SI NOTI CHE MUST E HAVE TO HANNO SIGNIFICATI SIMILI E INTERCAMBIABILI

SOLO ALLA FORMA AFFERMATIVA, OPPURE INTERROGATIVA. INVECE ALLA FORMA

NEGATIVA LA LORO DIFFERENZA E' NETTA:

–

MUSTN'T = NON DOVERE, QUINDI PROIBIZIONE, OBBLIGO DI NON FARE

–

DON'T HAVE TO = NON C'E' LA NECESSITA' DI, NON E' NECESSARIO FARE

Guardate questi esempi:

–

I mustn't go to bed late this evening (non devo andare a dormire tardi questa sera = sono

obbligata a non andare a dormire tardi) MA I don't have to get up early on Sundays (non

devo alzarmi presto di domenica = non sono obbligata, non ho la necessità)

–

you mustn't forget to do your homework (non devi dimenticare di fare i compiti = ti è

proibito non fare i compiti) MA you don't have to study this evening: there's no school

tomorow (non devi studiare questa sera: non c'è scuola domani = non sei costretta, non c'è la

necessità)

SHOULD è il condizionale del verbo dovere (dovrei, dovresti, dovrebbe, ecc). Come tutti gli

ausiliari, è uguale per tutte le persone: I-you-he-she-it-we-you-they should. Anch'esso è sempre

seguito dal un verbo all'infinito senza TO (you should eat something, NON you should to eat

something). La negativa di SHOULD è SHOULDN'T (contrazione di should not), e anch'esso è

uguale per tutte le persone. SHOULD e SHOULDN'T si usano per dare consigli o suggerimenti a

5

qualcuno oppure per dire che sarebbe il caso di fare qualcosa:

–

I shouldn't worry so much (non dovrei preoccuparmi così tanto)

–

you should see a doctor (dovresti andare da un dottore)

–

she shouldn't go to bed so late (non dovrebbe andare a letto così tardi).

In inglese si usano anche spesso le espressioni I THINK ... SHOULD e I DON'T THINK ...

SHOULD:

–

I think he should be more careful (penso che dovrebbe stare più attento)

–

I don't think we should listen to what they say (penso che non dovremmo dare ascolto a

quello che dicono)

SI NOTI CHE IN INGLESE SI DICE “I DON'T THINK … SHOULD”, E NON “I THINK ...

SHOULDN'T”

TIME CLAUSES (frasi subordinate temporali)

Le frasi subordinate temporali sono frasi che dipendono da una frase principale (main clause) che

danno maggiori informazioni riguardo al tempo in cui si svolge un'azione. Esse sono introdotte da

congiunzioni temporali, tra le quali le più comuni sono:

when (quando), before (prima), after (dopo), until/till (finché), while (mentre), as soon as (non

appena), unless (a meno che), as long as (fintanto che), in case (nel caso che), provided/providing

(sempre che), unless (a meno che).

Nelle frasi subordinate temporali riferite ad azioni che si svolgono nel presente oppure nel futuro si

può usare solo un tempo “present” inglese (present simple, present continuous, present perfect),

anche se il tempo present continuous non è molto usato. NOTA: anche se “if” (se) è una

congiunzione che introduce frasi subordinate condizionali, quando la frase subordinata condizionale

si riferisce al presente o al futuro, essa utilizza uno dei tempi “present” inglesi proprio come le frasi

subordinate temporali.

Guardate questi esempi:

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

When she’s big, she’ll become a doctor (quando sarà grande, diventerà una dottoressa*1)

Close the door after you go/ you’ve gone out (chiudi la porta dopo che esci/che sei uscito*1)

Before she goes, I have something to tell her (prima che lei vada, ho una cosa da dirle*1)

We’ll leave as soon as he arrives (partiremo non appena arriva*1)

Unless you have a passport, you can’t go to Africa (A meno che tu non abbia un passaporto,

non puoi andare in Africa*2)

Until he arrives, we won’t leave (finché non arriva, non partiremo*2)

Providing/provided you have a pass, you can access to the fair without paying (sempre che

tu abbia un pass, puoi accedere alla fiera senza pagare*3)

Take an umbrella in case it rains (prendi un ombrello nel caso (che) piova*3)

*1 Come si vede, anche in frasi dove in italiano si userebbe un tempo futuro oppure un congiuntivo,

in inglese si può solo usare un present simple, un present continuous o un present perfect.

*2 Con “unless” e “until” si usa il verbo all'affermativo, in altre parole in inglese si dice “a meno

che” e non “a meno che non”, e si dice “finché” e non “finché non”.

*3Con le congiunzioni “providing/provided” e “in case” la congiunzione italiana “che” (“that” in

inglese) viene sempre sottointesa.

6

LE FRASI PASSIVE

Una frase passiva, sia in italiano che in inglese, è una frase dove il soggetto subisce l'azione

espressa dal verbo anziché compierla. Per esempio, nella frase “la televisione è stata inventata da

Baird nel 1925”, non è la televisione che ha compiuto l'azione, ma essendo Baird che l'ha inventata,

è lui che ha compiuto l'azione. Nella lingua soprattutto parlata, una frase attiva, dove cioè il

soggetto compie l'azione, è generalmente sempre preferibile in quanto suona più natutale (la frase

“Pietro mi ha dato una mela” è decisamente più naturale di “una mela mi è stata data da Pietro).

Tuttavia, ci sono delle situazioni precise in cui una frase passiva è preferibile, oppure è l'unica frase

possibile; per esempio, ogni volta che il risultato dell'azione è più importante di chi l'ha compiuta si

usa una frase passiva, che ha proprio lo scopo di mettere in risalto il risultato. Per tornare

all'esempio di prima, la frase “la televisone è stata inventata da Baird nel 1925” suona meglio di

“Baird ha inventato la televisione nel 1925” se voglio concentrare l'attenzione sull'oggetto inventato

piuttosto che sul suo inventore. Addirittura potrei semplicemente dire “la televisione è stata

inventata nel 1925” e non esprimere da chi.

Le ragioni più frequenti per preferire una frase passiva ad una attiva sono le seguenti:

–

quando l'autore di un'azione è sconosciuto; esempio: “due uomini sono stati uccisi nella

periferia della nostra città”. Se non è stato individuato l'uccisore, il passivo è l'unica

soluzione);

–

quando chi compie un'azione è meno importante della cosa che ha compiuto. E' il caso, per

esempio, delle invenzioni e delle scoperte scientifiche; Esempio: “il DNA è stato scoperto

nel 1953” (chi l'ha scoperto non ci interessa).

–

quando non voglio indicare chi ha compiuto una azione perché è inappropriato o superfluo.

Esempio: ”il portone viene chiuso alle otto” suona sicuramente più efficaci di dire “il

custode, o chi lo sostituisce, chiude il portone alle otto”

–

situazioni nelle quali il testo si snoda meglio se si usa una forma passiva. Esempio: “I

lavoratori saranno retribuiti a fine opera”. La frase passiva risulta più chiara di una possibile

frase attiva, di difficile ideazione. Certo, potremmo cambiare verbo («i lavoratori

riceveranno la retribuzione»): ma per usare la frase attiva finiamo per ricorrere a un giro di

parole e quello che guadagniamo da una parte lo perdiamo dall'altra.

Il passivo in inglese funziona come in italiano (ad eccezione dei verbi con complemento di termine,

che funzionano in un altro modo), ovvero:

- Il soggetto della frase attiva diventa il complemento di agente della frase passiva (il

complemento di agente in italiano esprime chi ha compiuto un'azione in una frase di tipo

passivo, ed è introdotto sempre dalla preposizione “da”, che in inglese si traduce con la

preposizione “by”)

- Il complemento oggetto della frase attiva diventa il soggetto della frase passiva (si

ricorda che il complemento oggetto precisa l'oggetto dell'azione espressa dal verbo).

- Il verbo essere è coniugato nel tempo verbale in cui ci si esprime (se siamo al present

simple: “am”, “is” o “are”, se siamo al present perfect: “have been” o “has been”, e così

via )

- Il verbo dell’azione è al participio passato (-ed per i verbi regolari, 3° forma del

paradigma per quelli irregolari).

Esempi: I eat an apple (io mangio una mela) = an apple is eaten by me (una mela è mangiata da

me). Nella frase “I eat an apple”, “I” è il soggetto, “eat” è il verbo e “an apple” è il complemento

oggetto. Nella frase “an apple is eaten by me”, “an apple”, che era il soggetto della frase attiva, è

diventato il soggetto della frase passiva, “is eaten” è il verbo, mentre “by me” è il complemento di

agente.

7

Il seguente rappresenta uno schema della costruzione della frase passiva in tutti i tempi verbali

inglesi. Si noti che “DONE” rappresenta il participio passato (past participle) del verbo che esprime

l'azione, con cui andrà sostituito.

-

Present Simple

Present Continuous

Going to future

Will future

Present Perfect

Present Perfect Continuous *

Past simple

Past perfect

Past perfect Continuous *

Past continuous

Future perfect

Present Conditional

Past conditional

Modali al presente

Modali al passato

= am, is, are

= am, is, are being

= am, is, are going to be

= will be

= have, has been

= have, has been being

= was, were

+ DONE

= had been

= had been being

= was, were being

= will have been

= would be

= would have been

= could be, can be, must be, should be…

= could have been, must have been, should have been

*rarissimi

IL PASSIVO DEI VERBI CON COMPLEMENTO DI TERMINE

Il complemento di termine in italiano è quel complemento che risponde alla domanda “a chi?” o “a

che cosa?”. Esempi:

–

Giovanni diede un bacio a Maria

–

Gli risposi che non doveva preoccuparsi (gli = a lui)

–

Mi fu detto che era troppo tardi (mi = a me)

La grammatica inglese chiama il complemento oggetto “complement of direct object” (=

complemento di oggetto diretto) e il complemento di termine “complement of indirect object”

(complemento oggetto indiretto). La definizione “indiretto”, sia in italiano che in inglese, significa

che il complemento è introdotto da una preposizione. Ovviamente, “diretto” significa che il verbo è

transitivo e il complemento che segue il verbo non è introdotto da preposizioni (esempio: io mangio

la mela). Ma a differenza dell'italiano, che può formare una frase passiva solo da un verbo transitivo

con complemento oggetto, l'inglese può formare frasi passive anche con verbi che reggono sia il

complemento oggetto che il complemento di termine, e in quel caso sarà il complemento di termine

della frase attiva a diventare il complemento di agente della frase passiva. Studiate questo esempio:

–

Peter gave an apple to me (frase attiva) => I was given an apple by Peter (frase passiva;

letteralmente “io fui dato una mela da Peter”)

Una frase passiva del genere non sarebbe mai possibile in italiano, in quanto essa sarebbe espressa

“mi fu data una mela da Peter”.

Per semplificare il motivo per cui in inglese si può fare una frase passiva con un complemento di

termine, potremmo dire che in inglese i pronomi complemento (me, mi, gli, la, le, ecc.) sono uguali

sia per il complemento oggetto che per il complemento di termine:

–

me = me, a me, mi

–

you = te, a te, ti, voi, a voi, vi

–

him / it = lo, a lui, gli

–

her = la, a lei, le

–

us = noi, a noi, ci

8

them = li, a loro, loro

Essendoci un'unica forma per entrambi i complementi, il pronome complemento che esprime il

complemento di termine non si distingue da quello che esprime il complemento oggetto. Il risultato

di ciò è che il pronome complemento della frase attiva si trasforma in un pronome soggetto (I, you,

he, she, it, we, they) della frase passiva, e la preposizione “a” (“to” in inglese) non si mette.

QUESTO VALE PER TUTTI I VERBI CHE REGGONO SIA IL COMPLEMENTO OGGETTO

CHE IL COMPLEMENTO DI TERMINE. Alcuni verbi che reggono entrambi i complementi sono:

dire, rispondere, dare, promettere, vendere, offrire, comprare, fare, portare, credere, riferire, ecc.

Esempi:

–

she was told that she was clever (a lei/le fu detto che era in gamba)

–

we will be answered tomorrow (a noi/ci sarà risposto domani)

–

they were given some bad news (fu data a loro/loro una brutta notizia)

–

I have been promised a new bike (a me/mi è stata promessa una nuova bicicletta)

–

you are going to be offered a job opportunity (sta per esserti offerta una opportunità di

lavoro)

Se invece di un pronome complemento, nella frase attiva ci fosse un nome proprio, per trasformare

il complemento di termine in complemento di agente è sufficiente togliere la preposizione “a” (“to”

in inglese) davanti al nome. Esempi:

–

a John è stato detto di fare i compiti (frase attiva) = John has been told to do his homework

(frase passiva)

–

dissero a Mary che sua sorella stava morendo (frase attiva) = Mary was told that her sister

was dying

–

Si noti che esistono frasi italiane che hanno la seguente costruzione:

–

si dice che Tom si sia sposato

In una frase di questo tipo, la particella “si” in italiano si chiama “si passivante”, perché il

significato della frase è “e detto che Tom si sia sposato”, che è una frase passiva. Ogni volta che

dobbiamo tradurre frasi che contengono locuzioni verbali tipo “si dice, si pensa, si crede, si ritiene”,

ecc., le frasi si traducono come frasi passive:

–

si dice che Tom si sia sposato = Tom is said to have got married (letteralmente: Tom è detto

di essersi sposato)

–

si pensa che John si sia trasferito all'ester = John is thought to have moved abroad

–

si crede sempre che gli altri saranno onesti = the others are always believed to be honest.

ESERCIZIO: TRADUCETE QUESTE FRASI MANTENENDO IL TEMPO VERBALE IN CUI

SONO ESPRESSE IN ITALIANO:

–

LE FU DETTO DI ASPETTARE

____________________________________________________________________________

–

A JAMES E' STATO RECENTEMENTE PROMESSO UN NUOVO LAVORO

____________________________________________________________________________

–

A QUEL BAMBINO è COMPRATO UN REGALO OGNI GIORNO

____________________________________________________________________________

–

GLI SARA' VENDUTA QUELLA CASA

____________________________________________________________________________

–

MI E' STATO OFFERTO UN MAZZO DI FIORI

____________________________________________________________________________

–

A SARAH FU DETTO CHE NON PRENDEVA BUONI VOTI

____________________________________________________________________________

9

THE HISTORY OF BRITAIN

LIVELLI B1-B2

CHARLES I – KING FROM 1625 TO 1649

Charles I was king of England, Scotland and Ireland, whose conflicts with parliament led to civil

war and his eventual1 execution.

Charles I was born in Fife on 19 November 1600, the second son of James VI of Scotland and Anne

of Denmark. On the death of Elizabeth I in 1603 James became king of England and Ireland.

Charles's popular older brother Henry, whom2 he adored, died in 1612 from typhoid3 in 1612

leaving Charles as heir4. Four years later, Charles inherited the title of Prince of Wales from his

deceased brother, and in 1625 he became king. Three months after his accession he married

Henrietta Maria of France, a 15-year-old Catholic princess who refused to take part in English

Protestant ceremonies of state. They had a happy marriage and had six children, one of whom died.

Of the five surviving children, two would follow their father on the throne as Charles II and James

II.

THE BEGINNING OF HIS REIGN

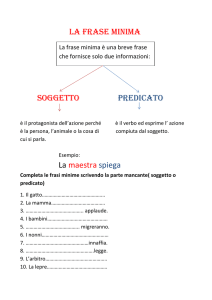

1 A portrait of King Charles I by Gerrit Van Honthorst

Charles had promised Parliament in 1624 that there

would be no advantages for Catholic people if he had

married a Roman Catholic person. But when he

married Henrietta, the French insisted on a

commitment5 to remove all disabilities upon Roman

Catholic subjects. Charles's lack6 of scruple was

shown by the fact that this commitment was secretly

added to the marriage treaty7, despite his promise to

Parliament.

Charles was reserved (he had a residual stammer8),

self-righteous9 and had a high concept of royal

authority, believing in the divine right of kings. He

was a good linguist and a sensitive man of refined

tastes. He spent a lot on the arts, inviting the artists

Van Dyck and Rubens to work in England, and

buying a great collection of paintings by Raphael and

Titian (this collection was later dispersed under

Cromwell). Charles I also instituted the post10 of

Master of the King's Music, involving supervision of

the King's large band of musicians; the post survives

today.

His expenditure on his court and his picture collection greatly increased the crown11's debts.

Charles's reign began with an unpopular friendship with George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, a

royal favourite of both James I and Charles I, who used his influence against the wishes of other

nobility. Charles had inherited disagreements12 with Parliament from his father, but his own actions

(particularly engaging13 in ill-fated14 wars with France and Spain at the same time) eventually

brought about15 a crisis in 1628-29: the expeditions to France were made to help the Huguenots

against Richelieu, but both the army and the navy had been neglected under James I, and England

could not challenge16 France and Spain together. A wiser17 policy would have been to maintain the

balance of power, trying to keep peace with France while Spain was master of such a large part of

Europe. Two expeditions to France failed - one of which had been led by Buckingham, who had

10

gained political influence and military power. Such18 was the general dislike of Buckingham, that he

was impeached19 by Parliament in 1628, although he was murdered the same year by a fanatic

before he could lead the second expedition to France.

PROBLEMS WITH PARLIAMENT

There was a lot of tension with parliament over money, and the House of Commons refused the

subsidies20 for these wars because of their high cost. In addition, Charles favoured a High Anglican

form of worship21, and his wife was Catholic - both made many of his subjects suspicious,

particularly the Puritans. Charles dissolved parliament three times between 1625 and 1629.

However, it is important that during the Parliament of 1628 the Commons agreed22 to grant23 a large

sum of money on condition that Charles should accept the Petition24 of Rights25, which had an

importance similar to the Magna Charta of the Great Charter26 of Liberties of 1215; two of the most

important rules of the Petition of Rights were that no man had to pay any tax not approved by

Parliament, and no man could be imprisoned arbitrarily.

In 1629, he dismissed parliament and decided to rule alone without its advice and the taxes which it

alone could grant legally. This forced him to find money by non-parliamentary means, which made

him increasingly unpopular.

Although27 opponents later called this period 'the Eleven Years' Tyranny', Charles's decision to rule

without Parliament was technically within28 the King's royal prerogative, and for someone the

absence of Parliament was better than new taxes established without it. For much of the 1630s, the

King gained most of the money he needed from measures like impositions, exploitation of forest

laws (sfruttameto delle leggi forestali), forced loans (prestiti forzosi), wardship (tutela) and, above

all, ship money (tassa imposta per la riscossione di denaro da destinare alla flotta navale, NdR),

extended in 1635 from ports to the whole country. These measures made him very unpopular,

alienating many who were the natural supporters of the Crown.

Things got worse when Charles made Cardinal Laud Archbishop of Canterbury: Laud was a great

churchman29, but he was not a statesman30, so he favoured the Catholics and persecuted the Puritans,

and many emigrated to the American colonies. When Laud tried to impose uniformity of worship

with a new prayer book on the Presbyterians of Scotland, the Scots rebelled against England.

Charles was forced to call parliament to obtain funds to fight the Scots. However, the Short

Parliament of April 1640 queried31 Charles's request for funds for war against the Scots and the king

dissolved it after a few weeks.

Charles was finally forced to call another Parliament in November 1640. This one, which came to

be known as The Long Parliament, did not grant money; instead32 it passed important acts in

opposition to the king: Cardinal Laud was imprisoned and later executed, it abolished the King's

Council (Star Chamber), and declared ship money and other fines33 illegal. The King agreed that

Parliament could not be dissolved without its own consent, and the Triennial Act of 1641 meant that

no more than three years could elapse34 between Parliaments. But when the Commons asked the

king to abandon the control of all military, civil and religious affairs, Charles refused, and attempted

to have five members of parliament arrested. This caused the beginning of a Civil war in August

1642: the king raised35 the royal standard (stendardo reale, ovvero un vessillo araldico che

rappresenta lo scudo delle armi reali, NdR) at Nottingham, calling for loyal subjects to support him;

Oxford became the King's capital during the war.

At first the fight was even36: Charles had the north, west and south-west of the country, and

Parliament had London, East Anglia and the south-east However, the Navy sided with Parliament

and Charles didn't have the resources to hire37 substantial mercenary help. Under strong generals

like Sir Thomas Fairfax and Oliver Cromwell, Parliament won victories at Marston Moor (1644)

and Naseby (1645).

In May 1646, Charles placed himself in the hands of the Scottish Army because he thought of

playing off38 one group against another, in fact, in Scotland and Ireland, factions were arguing,

while in England there were signs of division in Parliament between the Presbyterians and the

11

Independents; Charles saw the monarchy as the source of stability and told parliamentary

commanders 'you cannot be without me: you will fall to ruin if I do not sustain you'. After nine

months, the Scottish Army handed39 him to the English Parliament in return for money.

Charles's negotiations continued from his captivity at Carisbrooke Castle on the Isle of Wight, to

which he had escaped in November 1647, and led to the Engagement40 with the Scots, under which

the Scots would provide an army for Charles in exchange for the imposition of the Covenant41 on

England. This led to the second Civil War of 1648, which ended with Cromwell's victory at Preston

in August.

The Army, concluding that permanent peace was impossible while Charles lived, decided that the

King must be put on trial and executed. In December, Parliament was purged42, leaving a small

rump43 totally dependent on the Army, and the Rump Parliament established a High Court of

Justice. On 20 January 1649, Charles was charged with44 high treason45 'against the realm of

England'. Charles refused to plead46, saying that he did not recognise the legality of the High Court

(it had been established by a Commons purged of dissent, and without the House of Lords, and the

Commons never acted as a judicature). The King was sentenced to death on 27 January. Three days

later, Charles was beheaded47 on a scaffold48 outside the Banqueting House in Whitehall, London.

The King asked for warm clothing before his execution because he did not want the others to see

him shake49 and think that he was shaking for fear. On the scaffold, he repeated his case: 'I am the

martyr of the people.' His final words were 'I go from a corruptible to an incorruptible Crown,

where no disturbance can be.'.

All of this had tremendous consequences in Britain first and then in Europe: in Britain the

Monarchy disappeared for some time and a new phase of the British history started, called the

“Puritan Age”, which saw as a ruler Oliver Cromwell, one of the generals who granted the victory

of Parliament during the Civil War (this will be explained in the next number of Speak English!

Magazine). And even in Europe what happened was received as s shock, that a king could be judged

for his actions at the point of being put to death by his own people. Nothing like had ever happened

till then, and did not happen again until the French Revolution.

TO TALK TOGETHER:

- What were some of the characteristics of Charles I?

- Which problems were during is reign as regards war, money and Parliament?

- Why did a Civil War break out and who won it?

- Why was Charles I beheaded?

VOCABULARY

1 eventual: successivo

2 whom: chi (complemento ogg.)

3 typhoid: febbre tifoidea

4 heir: erede

5 commitment: impegno

6 lack: mancanza

7 treaty: trattato

8 stammer: balbuzie

9 self-righteous: moralista

10 post: carica

11 crown: corona

12 disagreement: dissapore

13 to engage: intraprendere

12

14 ill-fated: sfortunato

27 although: benché

40 engagement: impegno

15 to bring about: portare 28 within: all'interno di 41 covenant: alleanza

16 challenge: sfida

29 churchman: ecclesiastico 42 to purge: purgare

17 wiser: più saggio

30 statesman: statista

43 rump: groppa

18 such: tale

31 to query: interrogare 44 to charge with: accusare di

19 to impeach: mettere in stato d'accusa 32 instead: invece 45 treason: tradimento

20 subsidy: sussidio

33 fine: multa

46 to plead: implorare

21 worship: adorazione 34 to elapse: passare

47 to behead: decapitare

22 to agree: acconsentire 35 to raise: issare

48 scaffold: patibolo

23 to grant: concedere

36 even: pari, omogeneo 49 to shake: tremare

24 petition: petizione

37 to hire: assoldare

25 right: diritto

38 to play off: mettere l'uno contro l'altro

26 charter: atto costitutivo 39 to hand: consegnare

XÇzÄ|á{ _|àxÜtàâÜx tÇw cÉxàÜç

LIVELLI B2-C1

Metaphysicals and Cavaliers (1625-1660)

The conflicts and the confusion that marked the period between 1625 and 1660 were reflected in

literature, too. During the years that followed the death of Charles I, theatres were closed (for

reasons that will be explained in the next number of the “History of Britain” page. The closing of the

theatres marked the very end of the great season of drama and left the way clear for poetry and

prose.

POETRY

The poetry of this time is hardly1 classifiable into precise canons. Some writers (Fletcher, Wither)

went on imitating Spenser; others, the Metaphysical School (Herbert, Vaughan, Crashaw) followed

Donne (see the past number of the “English Literature and Poetry” page); others, the so-called

Cavalier or Caroline Poets (Carew, Suckling, Lovelace, Herrick) wrote in opposition to the rational

and intellectual spirit of Puritanism and used the classical metres of Ben Jonson. There were also

other writers, such as Marvell, who did not belong to any precise group, but combined the qualities

of the Metaphysicals and the Cavaliers in their verse.

Robert Herrick (1591-1674)

The son of a London goldsmith2, Herrick studied at Cambridge. He took orders in 1623. In 1629 he

was appointed3 Vicar of a Devon country parish4 which, in 1647, he had to leave because, as a

Royalist, he refused to swear an oath5 of loyalty to Parliament. Reinstated in his old position after

the restoration of the monarchy, he died there in 1674.

He wrote Hesperides, a collection of poems. A fervent disciple of Ben Jonson, he was influenced

by his classical paganism, especially in his love songs and pastoral lyrics. Like Jonson he turned

for inspiration to the ancient Roman poets, from whom he borrowed themes as well as names for

the women of his poems (Corinna, Julia, etc.). Here you can find an example of his poetry:

UPON JULIA'S CLOTHES

Whenas in silks my Julia goes,

Then, then, methinks, how sweetly flows

The liquefaction of her clothes.

Next, when I cast mine eyes, and see

That brave vibration, each way free,

O how that glittering taketh me!

SUI VESTITI DI GIULIA

Ogni quando in sete la mia Giulia va

Allora, allora, mi sembra, come dolcemente ricade

La liquefazione dei suoi vestiti.

Poi, quando poso i miei occhi, e vedo

Quella prode vibrazione, da ogni parte libera,

O quanto quello sfavillare mi prende!

The content is simple: when his Julia goes by6, dressed in silk7, her clothes seem to him to flow

with a kind of liquid motion ("liquefaction", I. 3). But when he sees her "free of clothes "(I. 5) he is

even more fascinated by the beauty of her "vibrant" naked body (1.6). The poem is very short (two

4-foot tercets rhyming a a a/b b b) but delightful. In only a few lines Herrick compresses images,

whose sweetness and immediacy are emphasized by the mixture of simple and learned8 words

and by the rhyme. In Herrick the theme of love is often accompanied by that of time passing, and

the consequent invitation to enjoy life as long as one can.

13

Andrew Marvell (1621-1678)

While Herrick belonged to the Cavalier Poets and Herbert to the Metaphysicals, Marvell, another

great poet of the time, distinguished himself from both of them, as he belonged to no school,

though combining the intensity of the Metaphysicals' imagery and the smoothness9 and

sophistication of the Cavaliers.

The son of a minister, he was educated at Cambridge. When the Civil War was over, he first

worked as a tutor and then became Latin Secretary, assisting John Milton during Cromwell's rule.

After the Restoration he became Member of Parliament. He died in 1678.

Among his works we remember his political pamphlets10 and “Miscellaneous Poems”, a collection

of lyrics. Among his lyrics, one of the best is certainly To His Coy Mistress, which we find

underneath:

TO HIS COY MISTRESS

ALLA SUA AMANTE RITROSA

Had we but world' enough, and time,

Sol che avessimo mondo e tempo sufficienti,

This coyness, Lady, were no crime.

Questa ritrosia, signora, non sarebbe un delitto.

We would sit down and think which way

Ci sederemmo e penseremmo da che parte

To walk and pass our long love's day.

Camminare e trascorrere il nostro lungo giorno d'amore.

Thou by the Indian Ganges' side

Tu sulla sponda dell'indiano Gange

Shouldst rubies find: I by the tide

troveresti rubini: io presso la corrente

Of Humber' would complain. I would

Dell'Humber mi lamenterei. Io vi

Love you ten years before the Flood,

Amerei dieci anni prima del Diluvio,

And you should, if you please, refuse

E voi ricusereste, se vi aggrada,

Till the conversation of the Jews.

Fino alla conversione dei Giudei.

My vegetable love should grow

Il mio amore vegetale crescerebbe

Vaster than empires, and more slow;

Più vasto degli imperi, e più lento;

An hundred years should go to praise

Cent'anni se ne andrebbero a lodare

Thine eyes and on thy forehead gaze;

I vostri occhi e a contemplare sulla vostra fronte;

Two hundred to adore each breast,

Duecento anni per adorare ogni seno,

But thirty thousand to the rest;

Ma trentamila per il resto;

An age at least to every part,

Un secolo almeno per ogni parte,

And the Last age should show your heart. E l'ultimo secolo scoprirebbe il vostro cuore.

For, Lady, you deserve this state,

Perché, signora, voi meritate questa condizione,

Nor would I love at lower rate.

Né io amerei a livello inferiore.

But at my back I always hear

Ma alle mie spalle sento sempre

Time's wingèd chariot hurrying near,

l'alato cocchio del tempo che si affretta ad avvicinarsi,

E laggiù tutto davanti a noi si estendono

And yonder all before us lie

Deserts of vast eternity.

Deserti di vasta eternità.

Thy beauty shall no more be found,

La tua bellezza non sarà più trovata,

Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound

Né, nella tua cripta marmorea risuonerà

My echoing song: then worms shall try

l'eco del mio canto: quindi vermi metteranno alla prova

That long-preserved virginity;

Quella verginità a lungo preservata;

And your quaint honour turn to dust,

E il vostro onore capriccioso si volgerà in polvere,

And into ashes all my lust:

E in cenere tutta la mia brama:

The grave's a fine and private place,

La tomba è un bello e appartato luogo,

But none, I think, do there embrace.

Ma nessuno, penso, là si abbraccia.

Now, therefore, while the yóuthful hue

Ora, pertanto, fintantoché il colore giovanile

Sits on thy skin like morning dew,

Si posa sulla tua pelle come rugiada mattutina.

And while thy willing soul transpires

E mentre la tua anima desiderosa traspira

At every pore with instant fires,

Ad ogni poro fuochi instantanei,

Now let us sport us while we may,

Ora prendiamo diletto fintantoché possiamo,

And now, like amorous birds of prey,

E ora, come amorosi uccelli da preda,

Rather at once our time devour

Meglio immediatamente il nostro tempo divorare

Than languish in his slow-chapped9 power. Che languire nelle sue lente fauci.

Let us roll all our strength and all

Avvolgiamo tutta la nostra forza e tutta

Our sweetness up into one ball,

La nostra dolcezza in un solo gomitolo

And tear our pleasures with rough strife

E sbraniamo i nostri piaceri con dura lotta

14

Thorough the iron gates of life.

Thus, though we cannot make our sun

Stand still, yet we will make him run.

Oltre i ferrei cancelli della vita.

Così, sebbene non possiamo il nostro sole far

Star fermo, quantomeno lo faremo correre.

Before commenting on it, it is interesting to remember that some words of the poem had a slightly

different meaning in the XVII century from today's. For example, coy meant "reluctant" and not

bashful11: mistress was a woman to whom a man pledged12 his love, and not a paramour13 or a

concubine; vegetable did not mean “dull”, but “vital” (the poet's love is similar to a plant growing

from a small sedd but slowly growing and expanding till becoming a big tree). “Quaint” (I. 29) did

not mean "strange' , but "capricious".

The poem can be divided into three parts:

Part 1 (Il. 1-20) — The poet addresses his mistress saying that, if there were more time and space

than there are in real life, her coyness would not be a crime, as there would be hundreds of years

for him to wait and adore and for her to refuse love before surrendering. Part 2 (Il. 21-32) — But

time is limited, its "chariot is hurrying near", her beauty will soon fade away14 and her "long

preserved virginity" will be violated by the worms in the grave. Part 3 (II. 33-46) — Therefore, he

concludes, let us enjoy ourselves as long as you are stili beautiful and I am full of love, and let us

"devour" time before being devoured by it.

The theme of the poem is "carpe diem" (seize15 the moment), but the poem is in fact a mixture of

humour, wit16 and sadness. Humour and wit characterize the first part, in which images and

descriptions are exaggerated on purpose17. Space is so dilated as to include both India (the

Ganges, I. 5) and England (the Humber, the river passing through Hull, the city where Marvell was

born, I. 7), where the two lovers, though close to each other, would live in a time which stretches18

from "ten years before the Flood" (I. 8) tilt "the conversion of the Jews" (I. 10), that is to say from

the beginning to the end of the world. Within this impossible universe, everything is excessive: the

poet's love would be "vaster than empires" (I. 12) and he could devote whole ages to adore the

various parts of his mistress's body, and the last one to discover ("show" I. 18) her heart.

But suddenly the tone changes. In the second part the consciousness of one's mortality introduces

a sombre note. India and England disappear into "deserts of vast eternity" (I. 24), an image which

sums up the two dimensions of time ("eternity") and space ("deserts") of the first lines. As to

"deserts", the term is by contrast connected to the "vegetable love" of line 11, as a desert is the

least suitable piace for growing anything. Time exists and brings death. Yet, more than on death,

the poet focuses his attention on the physical decay brought about by time, which will turn the

lady's "quaint honour" (I. 29) to dust and his own lust to ashes. The sadness of the lines is only

slightly tempered by the ironic description of the grave (Il. 31-32).

In the third part the poet's desire for physical love is more explicit. The rhythm becomes more

frantic19 through the use of verbs of motion ("sport" - "roll" - "tear" - "run"). The stanza is almost all

made up of contrasts: amorous/birds of prey (II. 38), devour/slow-chapped (Il. 39-40), strength/

sweetness (Il. 41-42), tear/pleasures (I. 43).

The conclusion is paradoxical: if we cannot stop the sun, we will make him run (II. 45-46), which

means that even though we cannot stop time, we can however master20 it by living intensely every

moment of our lives. The last two lines thus21 become a metaphor, which brings us back to the

main theme of the poem (i.e. "carpe diem"): in this world ravaged22 by time, only love, meant as

sex (symbol of life), can destroy time (symbol of death).

The poem is written in four-foot couplets rhyming aa/bb/cc, etc. Its structure is mostly based on

run-on lines, that is lines without an end-stop, whose sense runs over to the following one. Though

full of metaphysical elements (metaphors, contrasts, similes, paradoxes, macabre realism), it also

shows the musicality typical of the Cavaliers, together with their charm and their insistence on the

"carpe diem" theme.

VOCABULARY

1 hardly: difficilmente

2 goldsmith: orafo

3 to appoint: nominare

4 parish: parrocchia

5 oath: voto

6 to go by: passare

15

7 silk: seta

8 learned: colto

9 smoothness: uniformità

10 pamphlet: opuscolo

11 bashful: timido

12 to pledge: promettere

13 paramour: amante

19 frantic: frenetico

14 to fade away: svanire 20 to master: padroneggiare

15 to seize: cogliere

21 thus: così, pertanto

16 wit: spirito

22 ravaged: devastato

17 on purpose: di proposito

18 to stretch: estendersi

LET’S LAUGH TOGETHER!

LIVELLI A1-A2

JOKES ABOUT STUDENTS

Alfred: sir1, should2 anyone3 be punished

for something4 he hasn't done5?

Teacher: no, of course not

alfred: good, because I haven't done my

homework!

Teacher: jane, what's five and6 three?

Jane: I don't know, teacher.

Teacher: it's eight, of course.

Jane: but you said7 yesterday8 that four

and four is eight!

Teacher: Trevor, what do you know

about9 the Dead10 Sea?

Trevor : I didn't even11 know it was ill, Sir!

VOCABULARY

1 SIR: SIGNORE

2 SHOULD: DOVREBBE

3 ANYONE: QUALCUNO

4 SOMETHING: QUALCOSA

5 DONE: FATTO

6 AND: PIU' (QUI)

16

7 SAID: HA DETTO

8 YESTERDAY: IERI

9 ABOUT: RIGUARDO

10 DEAD: MORTO

11 NOT EVEN: NEMMENO

YOUR SPACE!

Nella pagina Your Space! di questo mese vengono pubblicati i lavori di due sorelle, Monica e Sonia

Zanutta, studentesse di Speak English! da due anni e ora all'inizio del livello B1. Il lavoro di

Monica rappresenta una presentazione di se stessa, mentre il lavoro di Sonia è la descrizione della

domenica precedente.

MONICA ZANUTTA

Hello!! My name's Monica Zanutta and I come from Marano in Italy. Marano is

a little town in the north of Italy. It's a very nice place in front of the sea.

I was born in Palmanova on 30 March 1975, and I lived with my family until

2002: in this year I married Simone.

When I was very young and I lived with my family, we were many... My parents

Almerino and Elda, my sisters Isabella, Romina and Sonia, and my brother

Enrico.

In the year 200s my daughter Gaia was born; she was and she is a wonderful

baby. I the year 2008 Simone and I divorced and Gaia and I went to live in

Marano.

I'm a shop keeper. I've got a shop with my sisters. In our shop we sell tiles and

articles for the bathroom and the living room.

In this moment my job Is very hard because we have many competitors but we

say...the show must go on!!

SONIA ZANUTTA

MY LAST SUNDAY

On Sunday morning the alarm clock rang at seven and I woke up ten minutes

later. I drank a cup of herbal tea with honey and then I ate half an apple.

I did some yoga exercise and then I went out for a run. I ran fifty minutes, I had a

shower and had breakfast with my children. After breakfast we wore our nice

clothes and went to church. After that we went to the bar for a glass of white wine

with friends.

At one pm we went back home for lunch: I cooked rice with pumpkin. My younger

son ate pasta with butter. He didn't like pumpkin because he thought that it was

the one that he saw on the wall last night. I told hi it wasn't, but he didn't believe

me.

After lunch we sat together on the sofa and read a book that we bought in the book

17

shop.

My younger son fell asleep immediately because he was tired. While he was

sleeping and I was reading, my older son drew something on a white sheet. When

it was half past three, Alessandro woke up and we decided to go out for a walk. We

drove to Palmanova and walked around this city on a beautiful meadow. Raffy

was very happy but Ale not so much, because he doesn't like walking. He walked

only because he knew that after that we would eat an ice-cream. We also saw some

boys ride some horses. After the walk we went to eat an ice-cream, I drank a coffee

and my husband preferred a juice.

At six o'clock we came back home. We bought a big pizza for dinner. At nine

o'clock we all went to bed.

18

BIBLIOGRAFIA

FIRST PAGE: Adattamento dell'articolo “How to make real friends”, tratto da Awake No.1,

edito dalla Congregazione Cristiana dei Testimoni di Geova

MONUMENTS OF BRITAIN:

- http://www.goldenhinde.com/archives/

- http://www.mitidelmare.it/Golden_Hind.htm

- https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Golden_Hind

Fotografia di Susanna Tagliavini

GRAMMAR: schede prodotte da Susanna Tagliavini

THE HISTORY OF BRITAIN:

- A Mirror of the Times, Rosa Marinoni Mingazzini & Luciana Salmoiraghi, 1989, Morano

Editore S.p.A, Napoli.

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/charles_i_king.shtml

- http://www.biography.com/people/charles-i-21388939#civil-war-and-death

http://www.royal.gov.uk/historyofthemonarchy/kingsandqueensoftheunitedkingdom/thestua

rts/charlesi.aspx

Fotogafia tratta da https://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Charles_I_of_England

ENGLISH LITERATURE AND POETRY:

- A Mirror of the Times, Rosa Marinoni Mingazzini & Luciana Salmoiraghi, 1989, Morano

Editore S.p.A, Napoli.

- Testi delle poesie tratti da A Mirror of the Times, op. cit. Traduzione di Susanna Tagliavini

LET'S LAUGH TOGETHER:

http://www.icbisuschio.it/med_cuasso/BARZELLETTE_file/BARZELLETTE.htm

YOUR SPACE: lavori di Monica e Sonia Zanutta

19