euro 40,00

ISBN 978-88-6927-012-3

i

ra

ld

ua

G

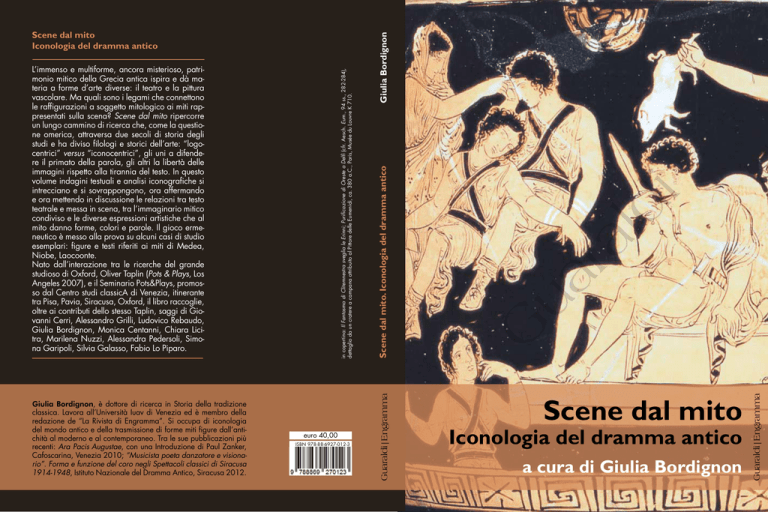

Scene dal mito. Iconologia del dramma antico

Giulia Bordignon

Scene dal mito

Iconologia del dramma antico

a cura di Giulia Bordignon

Guaraldi | Engramma

Giulia Bordignon, è dottore di ricerca in Storia della tradizione

classica. Lavora all’Università Iuav di Venezia ed è membro della

redazione de “La Rivista di Engramma”. Si occupa di iconologia

del mondo antico e della trasmissione di forme miti figure dall’antichità al moderno e al contemporaneo. Tra le sue pubblicazioni più

recenti: Ara Pacis Augustae, con una Introduzione di Paul Zanker,

Cafoscarina, Venezia 2010; “Musicista poeta danzatore e visionario”. Forma e funzione del coro negli Spettacoli classici di Siracusa

1914-1948, Istituto Nazionale del Dramma Antico, Siracusa 2012.

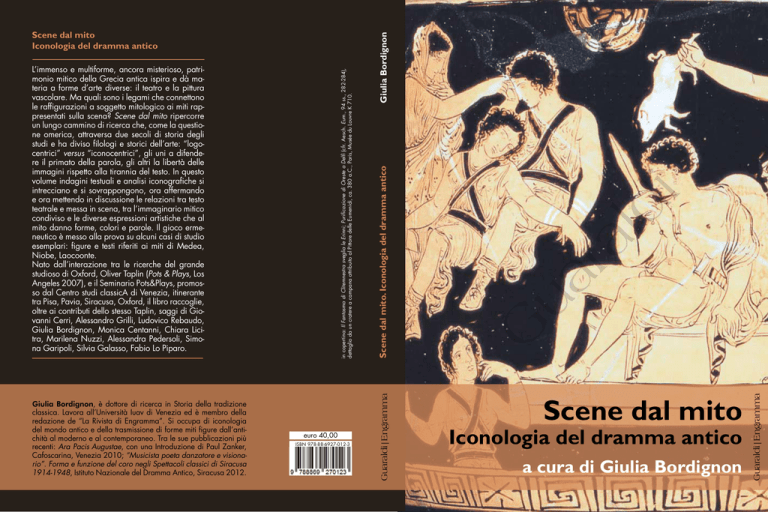

in copertina: Il Fantasma di Clitemnestra sveglia le Erinni; Purificazione di Oreste a Delfi (cfr. Aesch. Eum., 94 ss., 282-284),

dettaglio da un cratere a campana attribuito al Pittore delle Eumenidi, ca. 380 a.C., Paris, Musée du Louvre K 710.

L’immenso e multiforme, ancora misterioso, patrimonio mitico della Grecia antica ispira e dà materia a forme d’arte diverse: il teatro e la pittura

vascolare. Ma quali sono i legami che connettono

le raffigurazioni a soggetto mitologico ai miti rappresentati sulla scena? Scene dal mito ripercorre

un lungo cammino di ricerca che, come la questione omerica, attraversa due secoli di storia degli

studi e ha diviso filologi e storici dell’arte: “logocentrici” versus “iconocentrici”, gli uni a difendere il primato della parola, gli altri la libertà delle

immagini rispetto alla tirannia del testo. In questo

volume indagini testuali e analisi iconografiche si

intrecciano e si sovrappongono, ora affermando

e ora mettendo in discussione le relazioni tra testo

teatrale e messa in scena, tra l’immaginario mitico

condiviso e le diverse espressioni artistiche che al

mito danno forme, colori e parole. Il gioco ermeneutico è messo alla prova su alcuni casi di studio

esemplari: figure e testi riferiti ai miti di Medea,

Niobe, Laocoonte.

Nato dall’interazione tra le ricerche del grande

studioso di Oxford, Oliver Taplin (Pots & Plays, Los

Angeles 2007), e il Seminario Pots&Plays, promosso dal Centro studi classicA di Venezia, itinerante

tra Pisa, Pavia, Siracusa, Oxford, il libro raccoglie,

oltre ai contributi dello stesso Taplin, saggi di Giovanni Cerri, Alessandro Grilli, Ludovico Rebaudo,

Giulia Bordignon, Monica Centanni, Chiara Licitra, Marilena Nuzzi, Alessandra Pedersoli, Simona Garipoli, Silvia Galasso, Fabio Lo Piparo.

Guaraldi | Engramma

Scene dal mito

Iconologia del dramma antico

G

ua

ra

ld

i

Engramma | 4

i

ra

ld

ua

Comitato scientifico:

Benno Albrecht, Aldo Aymonino, Marco Biraghi, Francesco M. Cataluccio,

Monica Centanni, Maria Grazia Ciani, Alberto Ferlenga

G

Progetto grafico: Silvia Galasso e Jacopo Galli

Impaginazione ed editing: Silvia Galasso

Coordinamento redazionale: Alice Metulini

Copertina: Olivia Sara Carli

Con il contributo di Centro studi classicA | Università Iuav di Venezia

© 2015 by Guaraldi s.r.l.

Sede legale e redazione: via Novella 15, 47922 Rimini

Tel. 0541 742974/742497 - Fax 0541 742305

www.guaraldi.it - www.guaraldilab.com

[email protected] - [email protected]

ISBN carta 978-88-6927-012-3

ISBN pdf 978-88-6927-109-0

L’Editore dichiara di avere posto in essere le dovute attività di ricerca delle titolarità dei diritti sui contenuti qui pubblicati e

di avere impiegato ogni ragionevole sforzo per tale finalità, come richiesto dalla prassi editoriale e dalla normativa di settore.

i

ra

ld

Scene dal mito

Iconologia del dramma antico

G

ua

a cura di Giulia Bordignon

Guaraldi | Engramma

G

ra

ld

ua

i

Sommario

Presentazione 7

ra

ld

Questioni di metodo

i

a cura di Giulia Bordignon

11

About Pots & Plays

Pots&Plays. Teatro attico e iconografia vascolare:

appunti per un metodo di lettura e di interpretazione

25

Pots&Plays. Interactions between Oliver Taplin and the Italian Seminar

77

Il dialogo tragico e il ruolo della gestualità

85

Mito, tragedia e racconto per immagini nella ceramica greca

a soggetto mitologico (V-IV sec. a.C.): appunti per una semiotica comparata

ua

a cura del Seminario Pots&Plays

Oliver Taplin

Giovanni Cerri

G

Oliver Taplin

Alessandro Grilli

Teatro e archeologia: tra convenzione e innovazione iconografica

13

103

145

Teatro e innovazione nelle iconografie vascolari.

Qualche riflessione sul Pittore di Konnakis

147

Personificazioni di concetti astratti nelle rappresentazioni teatrali

e nelle raffigurazioni vascolari: alcuni esempi

163

Ludovico Rebaudo

Giulia Bordignon

Versioni testuali e versioni figurative: casi di studio

175

177

Il tema di ‘Niobe in lutto’

Ludovico Rebaudo

Il Laocoonte perduto di Sofocle:

una ricostruzione per fragmenta testuali e iconografici

205

Neottolemo o Diomede? Sul giovane imberbe al fianco di Odisseo nell’ambasciata a Lemno

229

Monica Centanni, Chiara Licitra, Marilena Nuzzi, Alessandra Pedersoli

Simona Garipoli

Pittura vascolare, mito e teatro: l’immagine di Medea tra VII e IV secolo a.C. 275

The Underworld Painter and the Corinthian adventures of Medeia.

An interpretation of the krater in Munich

303

Il canestro di Ione, la κίστη di Erittonio:

mitografia, drammaturgia e iconografia di un oggetto

313

Ludovico Rebaudo

Fabio Lo Piparo

Ricognizione critica e bibliografia generale

G

ua

a cura di Fabio Lo Piparo

i

Silvia Galasso

ra

ld

335

Presentazione

a cura di Giulia Bordignon

ra

ld

i

Personaggi, gesti, eventi: nello spazio aperto della scena teatrale, nel sintetico

spazio pittorico di un’anfora o di un cratere, le vicende del mito greco prendono forma dinnanzi ai nostri occhi, non solo e non tanto come narrazione,

ma come concreta rappresentazione, in cui l’elemento visuale gioca un ruolo

primario. In entrambi i casi – nella versione performativo-drammaturgica e

nella redazione artistico-figurativa – le forme del mito sono storicamente determinate, rispondono a criteri di composizione (e, insieme, di ricezione) che

costituiscono il proprium di ciascun mezzo espressivo.

G

ua

Le fonti dirette e le testimonianze scritte sulla pratica teatrale antica sono però,

come noto, scarse e non sempre affidabili: per la ricostruzione degli elementi

materiali (ambientazione scenica, costumi) e degli aspetti performativi delle

rappresentazioni drammatiche (movimenti, gestualità) alcune raffigurazioni

vascolari a soggetto mitico paiono allora configurarsi, mediante specifici indizi

iconografici, come un riferimento prezioso.

La considerazione delle raffigurazioni vascolari come ‘indicatori teatrali’ è un

campo di ricerca le cui esplorazioni – iniziate sporadicamente già nel XIX

secolo, con la nascita dell’archeologia come scienza positiva – si sono notevolmente intensificate negli ultimi vent’anni, in particolare grazie ai contributi sistematici pubblicati sul tema da Oliver Taplin (Comic Angels, 1993,

e Pots & Plays, 2007), sulla scia dell’opera di Trendall e Webster degli anni

Sessanta del secolo scorso. A partire dal lavoro dello studioso inglese, l’interesse per questo ambito di studi interdisciplinari – che coniuga filologia, archeologia, letteratura, visual studies – ha trovato sviluppo organico nel panorama scientifico italiano con l’attività di ricerca del Seminario Pots&Plays

promosso dal Centro studi classicA dell’Università Iuav di Venezia. I contributi

|

7

Giulia Bordignon

raccolti in questo volume sono frutto delle ricerche condotte – singolarmente

e collettivamente – dagli studiosi afferenti al seminario: si tratta di saggi di approfondimento metodologico e di applicazione a specifici case studies, cui si aggiunge, per l’introduzione e l’inquadramento del tema, la presenza autorevole

dello stesso Taplin, in generoso dialogo con gli spunti ermeneutici proposti dal

Seminario italiano. Da questo concerto di voci su un tema così complesso qual

è quello del rapporto tra rappresentazione teatrale e raffigurazione vascolare,

emergono prospettive di studio che spostano in avanti i confini, già pioneristici, delle proposte avanzate da Taplin.

ra

ld

i

Nel contributo corale Teatro attico e iconografia vascolare: appunti per un metodo di lettura e di interpretazione, il capitolo che delinea la storia degli studi

(pp. 56 ss.) basta già da solo a puntualizzare alcuni snodi problematici relativamente al rapporto tra testo teatrale e figurazione vascolare: l’approccio logocentrico oppure iconocentrico che impronta (ancora oggi) lo sguardo degli

studiosi in chiave disciplinare; l’orientamento ottimista oppure pessimista

rispetto alla possibilità delle immagini di fornire una mimetica ‘illustrazione’

del dramma greco.

ua

Nell’ambito generale degli studi storico-artistici il tentativo critico di dare

parola alle immagini è un’impresa difficile e pericolosa, perché nella traslitterazione dei criteri ermeneutici tra verbale e figurale il rischio è quello di

cadere in ‘improprietà di linguaggio’, se non in veri e propri fraintendimenti

del senso, poiché le immagini raramente possono essere “messe tra virgolette”

(così Squire 2009, 87).

G

È dunque necessario esaminare preventivamente, sullo sfondo delle coordinate storico-letterarie e delle indicazioni drammaturgiche già proprie della

teorizzazione antica – sottolineate in questo volume dal saggio di Giovanni

Cerri sulla gestualità tragica in rapporto con la Poetica aristotelica (pp. 85102) – i diversi codici che, nella narrazione della fabula-plot, caratterizzano

il dramma antico (come testo e come performance) e la pittura vascolare a

soggetto mitologico.

In questa direzione, la prospettiva semiotica del contributo di Alessandro

Grilli (pp. 103-143), che chiude la sezione metodologica, chiarisce il rapporto tra l’inscenamento dialogico del racconto mitico e la sua percezione

evenemenziale, in termini di esperienza estetico-percettiva. Questa disamina

risulta tanto più cogente laddove i sistemi semantici implicati nell’analisi – la

performance antica, la pittura vascolare – sono di per sé sfuggenti o lacunosi,

perché frutto di dinamiche di trasmissione non lineari. In questo senso sarà

8

|

Presentazione

sufficiente richiamare, qui, due aspetti problematici di fondo: l’alto numero

di tragedie che ci è noto esclusivamente per titoli o per frammenti, e il fatto

che il corpus dei vasi ricollegabili al mondo teatrale sia costituito quasi integralmente da manufatti di produzione coloniale magnogreca, di almeno un

secolo più tarda rispetto alla fioritura della tragedia in Atene.

ra

ld

i

Il parallelo simonideo tra pittura e poesia funziona essenzialmente se i poetici

silenzi della prima e le versicolori parole della seconda sono oggetto di una

ricezione sincronica: molto più difficile appare la lettura della “familiarità”

(così Oliver Taplin) con il teatro dei suoi – presunti – riflessi figurativi se si

considera la questione secondo una prospettiva diacronica. È questa, tuttavia, l’unica strada che appare criticamente fondata per prendere in esame un

fenomeno – quello della presenza nelle scene vascolari apule di ‘riverberi’ dal

mondo teatrale – distintamente presente al di là di ogni scetticismo, sebbene

secondo gradi e intenzioni che vanno studiati caso per caso.

G

ua

In questa direzione, il metodo di ricerca più produttivo sembra essere da un

lato quello dello studio degli specifici ambiti di creazione e dell’impianto

tipologico-formale dei manufatti (vd. qui i contributi di Ludovico Rebaudo sul Pittore di Konnakis, pp. 147-162, e sul cratere di Medea conservato

a Monaco, pp. 303-311); dall’altro lato, un passaggio metodologico indispensabile consiste nell’analisi delle varianti e delle cesure nella tradizione

mitografica e iconografica dei soggetti raffigurati: in questi casi possiamo

pensare che la fortuna di una determinata versione drammaturgica, innovando il racconto tradizionale, abbia avuto una ricaduta e una persistenza

anche nell’imagerie condivisa (vd. lo studio iconografico su Medea di Silvia

Galasso, pp. 275-302).

E solo soppesando il rapporto complesso dell’interdipendenza tra varianti –

mitiche, drammaturgico-performative e figurative – nel passaggio tra il mondo attico di V secolo e il mondo coloniale di IV secolo, si può effettivamente

gettare luce, con la dovuta acribia, sulla delicatissima questione filologica dei

testi tragici per noi perduti, come dimostrano i saggi di Monica Centanni et

all. sul Laocoonte di Sofocle (pp. 205-228) e di Simona Garipoli sulle versioni

tragiche del mito di Filottete (pp. 229-273).

Il racconto per parola e il racconto per immagine condividono spazi interstiziali ancora tutti da indagare, come sottolinea anche il contributo di Fabio

Lo Piparo sullo Ione euripideo che chiude il volume (pp. 313-333): l’analisi

filologica del testo si può dunque proficuamente coniugare con la disamina

|

9

Giulia Bordignon

delle testimonianze iconografiche e archeologiche nella creazione di un “paradigma indiziario” che dal mythos ci (ri)porta alla scena.

G

ua

ra

ld

i

Le reciproche risonanze avvertibili tra mito, teatro, prassi artistica si compongono allora in un quadro di allineamenti, deviazioni, metamorfosi e migrazioni: un campo di ricerca che possiamo definire come “iconologia del

dramma antico”.

Una prima versione dei contributi qui presentati è stata pubblicata ne “La Rivista di Engramma” <www.engramma.it> che dal 2010 riserva al tema di studio Pots&Plays particolare spazio e

attenzione; nell’ordine del Sommario di questo volume cfr.: Taplin 2010; Seminario Pots&Plays

2010; Taplin 2013; Cerri 2012; Grilli 2014a; Rebaudo 2013a; Bordignon 2013a; Centanni et

all. 2013; Garipoli 2013; Rebaudo 2012; Galasso 2013; Rebaudo 2013b; Lo Piparo 2014.

10

|

G

ua

ra

ld

i

Questioni di metodo

G

ra

ld

ua

i

About Pots & Plays

Oliver Taplin

ua

ra

ld

i

Interplay between theatre and the visual arts has been highly variable and

sporadic over the ages. While the eighteenth century produced a plethora of

paintings and engravings of actors in performance, for example, the era of

Shakespeare produced hardly anything (unfortunately). A rich, and relatively neglected, storehouse of theatre-related painting comes from the ancient

Greek world in the fourth century BC. There are well over 100 scenes of

comedies in performance surviving on painted ceramic vessels, and even more

scenes of mythological stories which are fascinatingly related to their theatrical

tellings in tragedy. I looked at Comedy in my book Comic Angels (1993): now

in Pots & Plays I have turned to Tragedy. In this presentation, my aim is to give

you some idea of how I have set about the subject in that book.

G

Take, for example, this strikingly ‘dramatic’ painting dating from about the

360s (fig. 1). The scene is emphatically set at Delphi, as is marked by several

signs, including the decorated omphalos (navel-stone), the Priestess in the upper left and Apollo himself to the right, with his name written in above his

head – quite a common feature. To the left below is a young man brandishing

a spear, to the right Orestes (named) with his sword drawn, and in the centre,

kneeling on the altar, Neoptolemos (named), already seriously wounded. This

is, then, the killing of Neoptolemos, son of Achilles, at Delphi, a well-known

myth – there was even a proverb “Neoptolemean revenge”, because he had

killed the aged Priam at the altar of Apollo at Troy. So, why should there be

any reason to connect this painting with tragedy? Could tragedy do anything

to help its appreciation?

Before facing these questions, some chronological and geographical setting.

The time is roughly the century between 420 and 320 BC; the place is the

Greek West, the Hellenic communities in Sicily and around the coasts of

|

13

G

ua

ra

ld

i

Oliver Taplin

1 | Death of Neoptolemos at Delphi, Apulian volute-krater, ca. 360s, attributed to the Ilioupersis Painter,

Milano, Collezione H. A. (Banca Intesa Collection) 239.

14

|

About Pots & Plays

southern Italy, often known as Magna Graecia, and especially Apulia (modern Puglia). Most of the Greek cities in this part of the world had been

founded way back before 650, so these are well-established communities,

many of great wealth and culture – it would be a mistake to think of them

as provincial or cut-off.

ra

ld

i

Around 430 BC a flourishing industry in red-figure painted pottery grew up

in the Greek West, displacing the Athenian imports which had held a virtual

monopoly of high-quality ceramics for more than a century. At just the same

time the spectacular and sensational new art-form of Theatre, both tragedy

and comedy, was spreading out from its metropolis of Athens to the whole

of the scattered Greek world. The great tragedians of fifth-century Athens,

especially Euripides, remained the most popular ‘classics’; but new tragedies

continued to be produced, and not only in Athens. Theatre-buildings and

travelling troupes developed, new playwrights and actors were recruited, not

least from Magna Graecia. For the Greeks in the West – and quite possibly for

their closely associated indigenous Italian neighbours also – fine painted pottery and tragic theatre coexisted as powerful and fresh subjects of appreciation

within their cultural, artistic and emotional worlds.

G

ua

Yet, despite this striking synchronism, there has been a strong tendency in the

last 30 years or so to reject any claimed connections between vase-painting

and theatre, to keep the two art-forms separate and autonomous. “Neoptolemos at Delphis – some scholars would say – is a perfectly complete picture

without any help from tragedy, thank you”. The title of a recent book, The

Parallel Worlds of Classical Art and Text (Small 2003), epitomises this reaction

against seeing the ‘infiltration’ of literature in art – or vice-versa. It is an irony

that this scepticism has coincided with the first publication of a very large

number of possibly relevant pots (nearly half of the 109 pots discussed in

detail in Pots & Plays are recent accessions). Many of these have been illegally

excavated and exported, especially from Puglia; but, for better or worse, they

are now known, and crying out for interpretation.

I counteract this trend away from interrelating theatre and painting in two

main ways. Firstly, I do not treat the issue as a matter of priority or superiority: the pictures are not ‘illustrations’ of theatre, nor are they ‘inspired by’

tragedies: the two coexist and inform each other; it is a matter of mutual enrichment not of dependence. Secondly, I show how tragedy at this time and

place is by no means a minority or elite experience: far from being a ‘text’,

accessible only to privileged readers, it is a performance seen by hundreds of

thousands every year, a pervasive shared experience. Why should people keep

|

15

Oliver Taplin

i

2 | Medeia on the snake-chariot, Lucanian calyxkrater, ca. 400, close to the Policoro Painter,

Cleveland, Museum of Art 1991.1.

ua

ra

ld

3 | Medeia on the snake-chariot, Lucanian hydria,

ca. 400, attributed to the Policoro Painter, Policoro,

Museo Nazionale della Siritide 35296.

G

their experiences of myths in the theatre compartmentalised separately from

their viewing of myths in paintings, especially if there are signals or links between them?

My thesis is that tragedy was one of the main ways, if not the main way, that

the mythological stories were known throughout Greece in this period. In

some cases we can be pretty sure that certain versions were actually invented

by the great tragedians of fifth-century Athens. In that case the painting is

necessarily connected, more or less closely, to the tragedy. The question is:

would seeing the play in performance enrich the appreciation of the painting?

Best to put this to the test of an example.

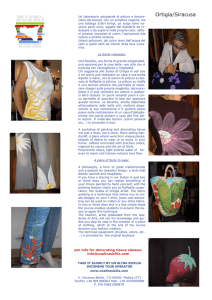

The splendid vessel showing Medeia in the chariot of the Sun was painted

as early as 400 BC – that is only some 30 years after the first performance of

Euripides’ celebrated tragedy Medeia (Euripides died in 406). And this vase,

excavated at Policoro/Herakleia in 1963, is of a similarly early date, and, while

16

|

About Pots & Plays

4 | Meeting of Orestes and Iphigeneia, ca. 360s,

Apulian volute-krater, attributed to the Ilioupersis

Painter, Napoli, Museo Archeologico Nazionale

82113 (H 3223).

ua

ra

ld

i

considerably simpler, has in fact very much the same iconography. Now, it is

nearly certain that Euripides actually invented the story that Medeia herself

killed her own children as revenge against Jason’s infidelity; and that he invented her escape from retribution by having her fly off in her grandfather’s

supernatural chariot. What is more, the final scene of Euripides’ play is made

around the superior power of Medeia, above and out of reach, over Jason who

protests helplessly below. This ‘spatial dynamic’ surely lends stronger power

to the composition of this painting. There are also undeniably differences between the painting and the play – above all the children are in the chariot with

Medeia in the Euripides – but these are far outweighed by the associations.

The painting does not ‘need’ the play, but it is enriched in meaning for those

who have seen this particular story in performance (on Medeia’s iconography

see infra Galasso, pp. 275-302, and Rebaudo, pp. 303-311).

G

I would say the same of this vase of ca. 360, showing Iphigeneia as a priestess, and her brother Orestes, as yet not identified as such, sitting on the altar

awaiting his execution as a sacrifice to Taurian Artemis. This whole story was

the invention of Euripides; and the vase will mean much more for someone

who know his play Iphigeneia in Tauris. You may have been struck by the

similarity between this composition and that by the same artist on the krater

with the scene of Neoptolemos at Delphi (fig. 1). But in this case it is a

matter of hearing rather than seeing the Euripidean tragic version. So far as

we know, it was Euripides in his Andromache who first brought Orestes into

the story of the death of Neoptolemos. The messenger in that play tells how

Orestes organised a cowardly ambush of the unsuspecting Neoptolemos,

while he was consulting the oracle at Delphi. The painting makes sense without the play, but it is that particular version that gives fuller significance

to the participation of Orestes and the way that he is lurking behind the

omphalos-stone. This is on a vessel known as a volute-krater (a wine-mixing

bowl with volute handles at the top). This became a favourite shape for the

|

17

Oliver Taplin

Apulian mythological vases, and as the fourth century went on they became

larger and larger (this one is 57 cm high), and more ornately painted, with

increasing use of white, yellow and purple paint.

G

ua

ra

ld

i

This type of monumental potting and painting reached its peak in the third

quarter of the fourth century; and its master was the prolific and inventive artist who is known as the Darius Painter. Here is a typical example of his work,

standing over a meter high. As in the messenger speech of Euripides’ famous

play, Hippolytos, the young man tries to control his horses which are being

maddened by the supernatural bull that is appearing before them. There are

two of the signals that are common in the tragedy-related pictures. One is the

bent old man to the left: he is the recurrent figure of the male carer (in Greek

paidagogos); and earlier in Euripides’ play he had tried in vain to warn Hippolytos against his arrogant attitude towards the goddess Aphrodite. Secondly there

is the ‘frieze’ of divinities above: it is a notable standard feature that they are

5 | Hippolytos trying to control his horses,

Apulian volute-krater, ca. 340s,

attributed to the Darius Painter,

London, British Museum F279.

6 | Death of Alkestis, Apulian loutrophoros,

ca. 340s, near the Laodamia Painter,

Basel, Antikenmuseum und Sammlung

Ludwig S21.

18

|

About Pots & Plays

calmly detached from the terrible human tragedy that is being enacted below.

ra

ld

i

This vase, like those related to Andromache and Iphigeneia in Tauris, came

originally from Apulia. So does this painting of the farewell of Alkestis, another celebrated Euripidean hit (note the paidagogos figure again). Likewise this

picture of Prometheus bound to a kind of stage-rock, probably alluding to Prometheus Unbound, a now lost play of Aeschylus. There was also a local school

of painters in Poseidonia/Paestum, which also shows awareness of tragedy.

The area of vase-painting with least artistic quality, and least direct relation

to theatre, was probably that from Campania, the large Italian hinterland of

the Bay of Naples, dominated by Capua. But there are some items of interest

from there, for example this relatively small vessel showing Orestes attacking

his mother Klytaimestra. In addition to the snake-bearing Fury (or Erinys) in

the upper right, a signal of the mother’s curses that will pursue Orestes, as in

the Aeschylus, notice the way that Klytaimestra is holding out her exposed

breast. In Aeschylus’ play Choephoroi, she tries (in vain) to stop Orestes from

killing her by appealing to “this breast” where he had fed as a baby. Again, the

picture means more to someone who knows the tragedy.

G

ua

In many ways, the most interesting area of production of Greek pottery painting in relation to the tragedy is Sicily. The Sicilian mythological paintings are

often closer to the practicalities of the theatre, revealing and exploiting an

awareness of the link with a particular tragedy. This is especially the case with

7 | Prometheus released by Herakles, Apulian calyx-krater, ca. 340s, attributed to the Branca Painter, Berlin,

Antikensammlung, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin 1969.9.

8 | The killing of Klytaimestra by Orestes, Paestan neck-amphora, ca. 330s, attributed to the Painter

of Würzburg, Malibu, J. Paul Getty Museum 80.ae.155.1.

|

19