50

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

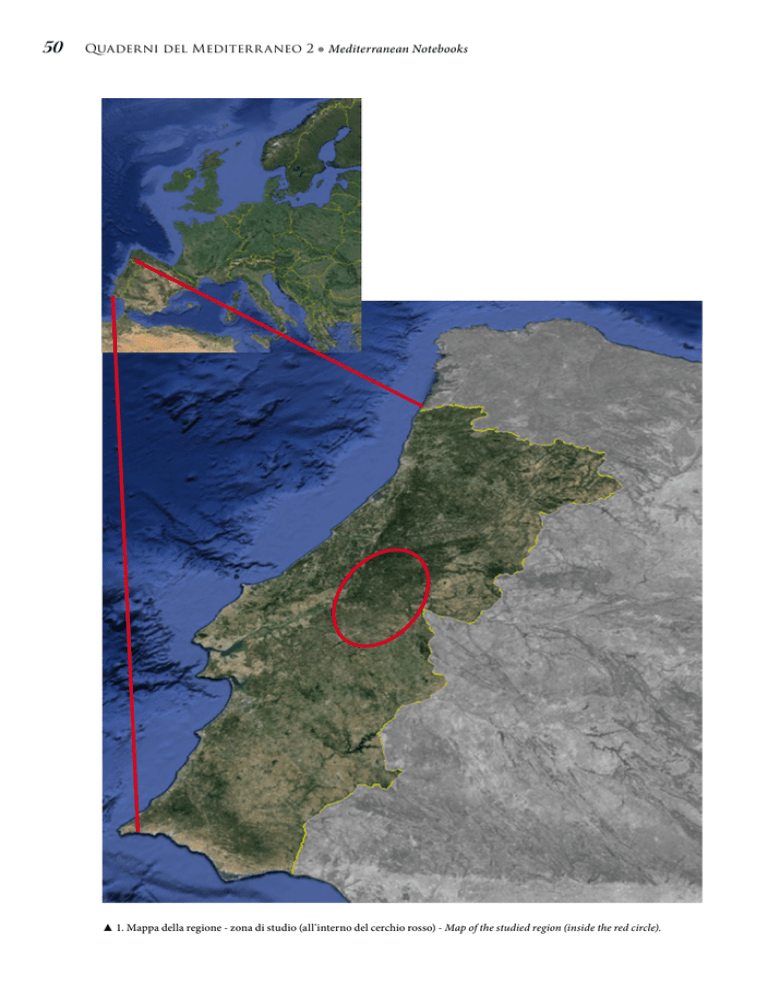

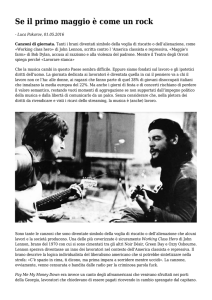

▲ 1. Mappa della regione - zona di studio (all'interno del cerchio rosso) - Map of the studied region (inside the red circle).

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

2. Arte rupestre filiforme e a “polissoir” tra i fiumi

Tago e Mondego (Portogallo):

Inventario, tipologia, paralleli e cronologia

INCISED ROCK ART BETWEEN THE TAGUS AND

MONDEGO RIVERS (PORTUGAL):

Inventory, typology, parallels and chronology

Fernando Coimbra

Centro Português de Geo-História e Pré-História - Grupo Quaternário e Pré-História do

Centro de Geociências (u. ID73 - FCT) - Instituto Terra e Memória

Sara Garcěs

Grupo Quaternário e Pré-História - do Centro de Geociências (u. ID73 - FCT)

Bolseira FCT (SFRH/BD/69625/2010) - Instituto Terra e Memória

INTRODUZIONE

Introduction

Note: In other articles in English, we called

“incised” to the rock art studied here. However, in Italian, the translation would provoke

misunderstanding. So we decided to classify,

in this article written in two languages, the

studied examples as “filiform and polissoir

rock art1”.

L'area studiata in questo articolo corrisponde al medio bacino dei fiumi Tago e

Mondego in Portogallo (Fig.1), essendo la

sua geologia caratterizzata principalmente

da rocce di scisto e grovacca.

L'arte rupestre che appare su queste superfici è prodotto da linee realizzate con una

pietra o un attrezzo metallico, più duro della

roccia.

I motivi rappresentati nelle incisioni rupestri appaiono sia con scanalatura sottile (filiforme1) o con scanalatura medio / spessa.

Questa distinzione è stata raramente menzionata nella bibliografia pubblicata, salvo il caso

di A. Domínguez García e Mª Amparo Aldecoa Quintana (2007), oltre ai nostri articoli.

The area studied in this article corresponds to the middle basin of the Tagus and

the Mondego rivers in Portugal (Fig.1), being

its geology characterized mainly by schist

greywacke rocks.

The rock art which appears on these surfaces is produced by carved lines made with

a stone or a metal tool, harder than the rock.

1. La parola filiforme deriva dal termine latino

filium (molto sottile, come un capello) e forma

(forma). Così non è appropriato denominare

"filiforme" un motivo fatto con una scanalatura più

spessa.

1. The word filiform comes from the Latin filium

(very thin, like an hair) and forma (shape). Thus

it’s inappropriate to denominate “filiform” a motif

done with a medium or a thick groove.

51

52

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

I motivi filiformi sono solo graffiti sulle

superfici rocciose, mentre gli altri vengono prima incisi e poi ripassati con movimenti ripetuti, con l'uso di una tecnica di

"polissoir".

L’arte rupestre filiforme e a polissoir può

essere trovata con una tipologia comune in

molti paesi dell'Europa meridionale, soprattutto in alcune regioni del Portogallo (Trásos-Montes, Alto Douro, Beira Interior, Alentejo), Spagna (Extremadura, Castilla y Léon,

Cataluña), Andorra, Francia (Pirenei orientali, Alpi francesi, Corsica) e Italia (Liguria,

Val d'Aosta, Piemonte, Lombardia, Puglia,

Sardegna). Alcune figure appaiono anche,

ma meno frequentemente, in Austria, Kosovo, ex Repubblica jugoslava di Macedonia,

la Grecia e la Romania (COIMBRA, 2013b).

Nella prima parte di questo articolo descriviamo l'inventario di arte rupestre incisa rilevata tra i fiumi Tago e Mondego. In secondo

luogo si stabilisce la sua tipologia, indicando

anche alcuni paralleli in Europa. Una terza

parte riguarda la problematica della cronologia di questo tipo di arte e dei risultati delle

recenti scoperte che possono meglio chiarire

la datazione di alcuni esempi.

In un prossimo futuro programmeremo

di effettuare la tracciatura di notte con luce

artificiale e cioè sulle rocce, note da diversi

decenni come Pedra Letreira de Góis, perché

potrebbero rilevarsi alcuni motivi molto sottili (e probabilmente non ancora rilevati). La

stessa procedura sarà applicata a sovrapposizioni che appaiono su Roccia 1 da Figueiredo.

The motives appear either with very thin

or with medium/thick grooves, being the

first usually called filiform and the second

“polissoir”. The distinguishing regarding the

grooves’ thickness has been rarely mentioned

in the published bibliography, except for the

case of A. Domínguez García and Mª Amparo

Aldecoa Quintana (2007), besides our own

articles.

Filiform motives are just scratched on the

rock surfaces, while the others are first carved

and then polished with repeated movements,

after the use of a “polissoir” technique.

Filiform and polissoir rock art can be found

with a common typology in many countries

from Southern Europe, mainly in several regions from Portugal (Trás-os-Montes, Alto

Douro, Beira Interior, Alentejo), Spain (Extremadura, Castilla y Léon, Cataluña), Andorra, France (Eastern Pyrenees, French

Alps, Corsica) and Italy (Liguria, Val d’Aosta,

Piemonte, Lombardy, Puglia, Sardinia). Some

motives appear also, but less frequently, in

Austria, Kosovo, FYR of Macedonia, Greece

and Romania (COIMBRA, 2013b).

In the first part of this article we make the

inventory of the filiform and polissoir rock

art which exists between the Tagus and the

Mondego rivers. Secondly we establish its typology, indicating also some parallels in Europe. A third part concerns the problematic

of the chronology of this kind of art and the

results of recent discoveries which can better

elucidate the dating of some examples.

In a near future we plan to do night tracing

with artificial light namely in rocks published

several decades ago such as Pedra Letreira de

Góis, because some motives very thin (and

probably not yet seen) may occur. The same

procedure will be applied to superimpositions

that appear on Rock 1 from Figueiredo.

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

2. INVENTARIO

Inventory

L'elenco dei siti con incisioni rupestri filiformi e a polissoir è presentato qui da Nord

a Sud della zona studiata, con esempi dei

distretti di Coimbra, Castelo Branco, Santarém e Portalegre.

1.1 - Distretto di Coimbra

In questo distretto, l’arte rupestre appare

in due comuni: Góis e Pampilhosa da Serra.

1.1.1 - Comune di Góis

In questa zona vi è una pietra molto importante, stranamente studiata solo alla fine

degli anni Cinquanta (BARROS et alli, 1959),

senza indagini più recenti. E’ nota come Pedra Letreira, che significa “pietra con lettere”, perché l’immaginazione popolare ha

interpretato i segni scolpiti sulla superficie

della roccia come un antico alfabeto.

I motivi consistono principalmente sulle

punte di freccia e reticoli, esiste anche un arco

con la freccia2 e due possibili scudi (Fig.2).

1.1.2 - Comune di Pampilhosa da Serra

Nel territorio del comune di Pampilhosa

da Serra, le rocce con motivi filiformi sono

tre: Roccia 5 da Cabeço do Malhadinho, Roccia 3 e Roccia 9 da Pico da Cebola3. Secondo

Batata e Gaspar (2011), la prima presenta

2. Il disegno del 1959 mostra due archi con la

freccia. Tuttavia una grande crepa, prodotta probabilmente da un incendio e non registrata sul

disegno, occupa l'area del secondo arco, che non

esiste più.

3. Questa roccia è stato scoperta in una zona

dove otto rocce con motivi a martellina sono stati

identificati da Batata & Gaspar ( 2011). Dal momento che è la nona roccia in questo complesso,

abbiamo deciso di seguire la numerazione di

quegli autori.

The list of sites with filiform and polissoir rock art

is presented here from North to South of the studied

area, with examples from the districts of Coimbra,

Castelo Branco, Santarém and Portalegre.

1.1 - District of Coimbra

In this District, this kind of rock art appears in

two municipalities: Góis and Pampilhosa da Serra.

1.1.1 - Municipality of Góis

In this area there is one very important rock,

strangely studied only in the end of the fifties (BARROS et alli, 1959), without more recent surveys. It’s

called Pedra Letreira, meaning stone with letters,

because popular mentality interpreted the signs

carved on the rock surface as an ancient alphabet.

The motives consist mostly on arrow heads and

net-patterns, existing also a bow with arrow2 and

two possible shields (Fig.2).

1.1.2 - Municipality of Pampilhosa da Serra

In Pampilhosa da Serra, the rocks with filiform

motives are three: Rock 5 from Cabeço do Malhadinho, Rock 3 and Rock 9 from Pico da Cebola3.

According to Batata & Gaspar (2011) the first one

presents several thin motives, which are difficult to

characterize due to several lichen that cover part of

them. Rock 3 from Pico da Cebola has also filiform

engravings among which the same authors identified a cross and a “D”. Rock 9 from Pico da Cebola

2. The drawing from 1959 shows two bows with

arrow. However a big crack, produced possibly

by a forest fire and not recorded on the drawing,

occupies the area of the second bow, which

doesn’t exist anymore.

3. This rock was discovered in an area where

eight rocks with pecked motives were identified

by Batata & Gaspar (2011). Since it’s the 9th

rock in this complex, we decided to follow the

counting of those authors.

53

54

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

▲ 2.Punte di freccie (Pedra Letreira de Gois) – Arrow heads (Pedra letreira de Gois)

diversi motivi filiformi, che sono difficili da

interpretare a causa di diversi licheni che coprono una parte di essi. Roccia 3 da Pico da

Cebola ha anche incisioni filiformi tra cui gli

stessi autori hanno individuato una croce e

una "D". La Roccia 9 da Pico da Cebola ha linee parallele e una possibile zig-zag, oltre ad

altri motivi metà ricoperti di licheni. Questa

roccia è un nuovo caso di incisioni filiformi,

recentemente scoperto da F. Coimbra e S.

Garcês e non ancora studiato.

1.2 - Distretto di Castelo Branco

Testimonianze di arte rupestre nel distretto di

Castelo Branco sono state ritrovate nei comuni

di Oleiros, Sertã e Proença-a-Nova. Sertã ha due

delle più importanti rocce della zona studiata, a

causa della varietà di segni e anche per la rarità

di alcuni di essi, come verrà descritto più avanti.

1.2.1 - Comune di Oleiros

Nella zona orientale della Serra do Cabeço

Rainho, nel sito chiamato Alto do Pobral, c'è una

roccia con motivi filiformi, costituito da due pic-

has parallel lines and a possible zig-zag, besides

other motives half covered with lichen. This rock is a

new case of filiform engravings, recently discovered

by F. Coimbra and S. Garcês but not yet properly

studied.

1.2 - District of Castelo Branco

The filiform and polissoir rock art from

Castelo Branco can be seen in the municipalities of Oleiros, Sertã and Proença-a-Nova.

Sertã has two of the most important rocks of

the studied area, due to the diversity of motives and also to the rarity of some of them, as

it will be explained later.

1.2.1 - Municipality of Oleiros

In the Eastern area of Serra do Cabeço

Rainho, at the place called Alto do Pobral,

there’s a rock with filiform motives, consisting of two small broken lines, which may constitute a small zigzag, or, in the opinion of its

discoverers, may represent the letter M of an

eventual Roman inscription (CANINAS et

alli, 2004). However, in Rock 2 from Figue-

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

cole linee spezzate, che possono costituire un piccolo zig-zag, o, secondo il parere dei suoi scopritori, può rappresentare la lettera M di un eventuale

iscrizione romana (CANINAS et alli, 2004). Tuttavia, sulla Roccia 2 da Figueiredo (Sertã), ci sono

due motivi simili con la stessa patina di altre incisioni di una chiara cronologia pre-romana, non

si tratta, in questo caso, della rappresentazione di

una lettera (COIMBRA - GARCÊS, 2013).

1.2.2 - Comune di Sertã

In questo comune sono state rilevate tre rocce

con motivi filiformi e a polissoir nella parrocchia

di Figueiredo. Su Roccia 1, alcune delle incisioni

sono state realizzate con scanalature media / spessa: un ascia senza manico, un albero, due pentagrammi, diversi reticoli, scalariformi, rettangoli

e quadrati di tipologia diversa, e linee parallele

e convergenti. C'è anche una possibile vulva, un

possibile scudo e quattro iscrizioni, essendo due di

loro preromana e gli altri di epoca romana.

Altre incisioni sono state eseguite con la tecnica

filiforme: due punte di freccia, due pentagrammi,

un albero, un zigzag, diversi reticoli, rettangoli e

quadrati, e gruppi di linee parallele e convergenti.

Ci sono diverse sovrapposizioni di incisioni

(Fig. 3), essendo uno di loro fatto con un motivo

databile4.

La Roccia 2 di Figueiredo è stata scoperta inaspettatamente da uno di noi (F. Coimbra) e C. Batata, durante una visita a Roccia 1 nel 2004, al fine

di realizzare le fotografie per una pubblicazione.

Un recente incendio boschivo aveva bruciato la

vegetazione intorno a questa pietra, che è piatta a

terra, e ha permesso di identificare alcuni motivi

filiformi. Solo quattro anni più tardi, nel quadro

del Progetto Ruptejo, c'era la possibilità di studiare

questa nuova roccia (Fig.4), che doveva essere accuratamente scavata, con strumenti di legno e di

plastica, perché era coperta di terra5 nella maggior

parte della sua area.

iredo (Sertã), there are two similar motives

with the same patina of other engravings of

a clear pre-Roman chronology, not being, in

this case, the representation of a letter (COIMBRA & GARCÊS, 2013).

1.2.2 - Municipality of Sertã

This municipality has three rocks with filiform and polissoir motives in the parish of

Figueiredo. In Rock 1, some of the engravings

were made with medium/thick grooves: an

axe without handle, a tree like motif, two pentagrams, several net-patterns, scalariforms,

rectangles and squares of diverse typology,

parallel and convergent lines. There’s also a

possible vulva, a possible shield and four inscriptions, being two of them pre Roman and

the others from the Roman Period.

Other engravings were made with filiform

technique: two arrow heads, two pentagrams,

a tree like motif, a zigzag, several net-paterns,

rectangles and squares, and groups of convergent and parallel lines.

There are several superimpositions of engravings (Fig. 3), being one of them made with

a datable4 motif .

Rock 2 from Figueiredo was discovered unexpectedly by one of us (F. COIMBRA) and

by C. Batata, during a visit to Rock 1 in 2004,

in order to make photographs for publication.

A recent forest fire had burned the vegetation

around this rock, which is flat to the ground,

and allowed to identify some filiform motives.

Only four years later, within the framework of

the Ruptejo Project, there was a possibility to

study this new rock (Fig.4), which had to be

carefully excavated, with plastic and wooden

tools, because it was covered with ground5 in

most of its area.

4. E' il caso di un rettangolo con linee interne, al

di sotto un'iscrizione romana del 1° secolo dC,

che costituisce un terminus ante quem per la sua

cronologia.

4. It’s the case of a rectangle with internal lines,

below a Roman inscription from the 1st century

AD, which constitutes a terminus ante quem for

its chronology.

5. Questo ha contribuito alla buona conservazione

delle incisioni.

5. This fact contributed for the good conservation

of the engravings.

55

56

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

▲ 3. Sovrapposizioni nella Roccia 1 da Figueiredo.

Rosso: punta di freccia, scudo (?) e iscrizione preromana.

Arancio: rettangolo con linee interne sottoposto per la iscrizione romana MIITAMVS. Negro: altri motivi.

Red: Arrow head, shield (?) and pre Roman inscription.

Orange: rectangle with internal lines overlapped by the Roman inscription MIITAMVS. Black: other motives.

Questa roccia ha rivelato motivi filiformi

come ad esempio: una figura antropomorfa a

croce, zig-zag (semplice e doppio), un triangolo (pugnale?), pentagrammi, un arco con

la freccia (Fig. 5) e un "asterisco". Presenta

anche incisioni con scanalature di medio

spessore, come: rettangoli, scalariformi, cruciformi, linee parallele e convergenti.

La Roccia 3 di Figueiredo è stato scoperta nelle stesse condizioni di Roccia 2 ed era

anche necessario scavare il sito attentamente, quello che è stato fatto anche nel 2008. E’

la più piccola e la meno importante roccia di

questa zona, avendo solo alcune incisioni filiformi senza presentare alcun motivo comprensibile.

1.2.3 - Comune di Proença-a-Nova

Presso Várzea Grande, parrocchia di Pro-

This rock revealed filiform motives such as:

a cruciform anthropomorphic figure, zigzags

(simple and double), a triangle (dagger?), pentagrams, a bow with arrow (Fig. 5) and an “asterisk”. It has also engravings with medium/

thick grooves, like: rectangles, scalariforms,

cruciforms, parallel and convergent lines.

Rock 3 from Figueiredo was discovered

in the same conditions of Rock 2 and it was

also necessary to be carefully excavated,

what take place also in 2008. It’s the smaller and the less important rock of this area,

having only some filiform incisions without making any understandable motif.

1.2.3 - Municipality of Proença-a-Nova.

In the place of Várzea Grande, parish of

Proença-a-Nova, there’s “Pedra das Letras”

(stone with letters). It was discovered in 1939

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

▲ 4. Roccia 2 da Figueiredo dopo gli scavi - Rock 2 from Figueiredo after excavation.

▲ 5/5A - Arco con freccie di tipo filiforme. Foto e rilievo - Filiform bow with arrow. Photo and tracing.

57

58

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

ença-a-Nova, è situata "Pedra das Letras"

(pietra con le lettere). E' stata scoperta nel

1939 da padre Henrique Louro, che ha interpretato le incisioni come caratteri di scrittura iberica. I motivi scolpiti consistono in

gruppi di linee parallele e convergenti realizzati con scanalature medio/spesse (Fig. 6).

Un rilievo completo è stato effettuato nel

1991 da Thomas Bubner, essendo i disegni

conservati presso il Laboratorio di Arte Rupestre da Instituto Terra e Memoria (Mação,

Portogallo).

Più recentemente questa roccia fu profondamente studiata da F. Henriques e JC Caninas

(2009).

Secondo le informazioni personali del Presidente della Parrocchia di São Pedro do Esteval

(comune di Proença-a-Nova), c'erano alcune

incisioni in un'area attualmente sommersa dalle

acque della diga di Pracana. Pertanto, altre incisioni potranno apparire se, in futuro, sarà possibile abbassare il livello delle acque della diga.

1.3 - Distretto di Santarém

In questa area, solo il comune di Mação ha

testimonianze di arte rupestre. Essa può essere

vista in due siti: vicino al fiume Ocreza e, fino al

nord, a Ribeira de Pracana un piccolo affluente

del Ocreza.

by father Henrique Louro, which interpreted

the engravings as characters of Iberian writing. The carved motives consist in sets of

parallel and convergent lines made with medium/thick grooves (Fig.6). A full tracing was

carried out in 1991 by Thomas Bubner, being

the drawings kept in the Laboratory of Rock

Art from Instituto Terra e Memória (Mação,

Portugal). More recently this rock was deeply

studied by F. Henriques e J.C. Caninas (2009).

According to personal information from the

President of the Parish of São Pedro do Esteval (municipality of Proença-a-Nova), there

were some engravings in an area currently

submerged by the waters of the dam of Pracana. This way, more filiform and polissoir

engravings (or pecked) can appear if, in the

future, it will be possible to low the level of the

waters from the dam.

1.3 - District of Santarém

In this district, only the municipality of

Mação has evidences of rock art. It can be

seen in two places: near the river Ocreza and,

up to the north, in Ribeira de Pracana a small

tributary of the Ocreza.

1.3.1 - Fiume Ocreza

La prospezione effettuata nel 2001, nel quadro

degli studi riguardanti l'impatto ambientale causato dalla costruzione dell’ autostrada A23, ha

permesso di scoprire alcune rocce con incisioni filiformi. Vicino alla linea d'acqua del fiume

Ocreza sono stati identificati sette6 rocce: Rocce

1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9 e 13 (Oosterbeek, 2003). Le Rocce

4, 5, 6 e 7 presentano solo alcune linee filiformi

senza costituire un motivo noto. La Roccia 1 ha

una incisione triangolare, che secondo alcuni autori può essere la rappresentazione di un pugnale

(Oosterbeek, 2002; 2003), un esempio simile

1.3.1 - River Ocreza

Prospecting carried out in 2001, in the

framework of the studies regarding the environmental impact caused by motorway A23,

allowed to discover some rocks with filiform

engravings. Close to the water line of river

Ocreza seven rocks6 were identified: Rocks 1,

4, 5, 6, 7, 9 and 13 (Oosterbeek, 2003). Rocks

4, 5, 6 and 7 present only some filiform lines

without constituting a known motif. Rock 1

has a triangular engraving, which according to some authors can be the depiction of a

dagger (Oosterbeek, 2002; 2003), existing a

similar example on Rock 2 from Figueiredo

(Sertã). The engravings from Rock 9 consist in

a set of parallel lines, while on Rock 13 it’s pos-

6. Altre rocce, non menzionate qui, presentano

motivi a martellina, e non sono considerate in

questo articolo.

6 Other rocks, not mentioned here, present

pecked motives, which are not considered in this

article.

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

esistente in Roccia 2 da Figueiredo (Sertã). Le

incisioni di Roccia 9 consistono in una serie di

linee parallele, mentre sulla Roccia 13 è possibile

osservare una sorta di "asterisco" (Coimbra &

Garcês 2013: Fig. 2).

1.3.2 - Ribeira de Pracana

In questa zona della Valle Ocreza due rocce

devono essere considerate: Roccia 12 e Roccia

21. La prima presenta molte linee filiformi senza

costituire un motivo.

Nella seconda, c'è una serie di linee parallele e

una possibile freccia (Monteiro; Gomes 19741977). Questa roccia, che ha anche un centinaio

di coppelle a martellina, è molto vicino alla linea

di livello d’acqua e nei periodi di maggiore flusso

resta parzialmente sommersa, ciò che aumenta

la sua erosione.

1.4 - Distretto di Portalegre

Come Santarém, nel distretto di Portalegre le testimonianze di arte rupestre

▲ 6. - Pedra das Letras, Proença-a-Nova.

sible to observe a sort of "asterisk” (Coimbra

& Garcês, 2013, Fig. 2).

1.3.2 - Ribeira de Pracana

In this area of the Ocreza Valley two rocks

must be considered: Rock 12 and Rock 21. The

first presents many filiform lines without constituting a motif. In the second, there’s a set

of parallel lines and a possible arrow (Monteiro; Gomes 1974-1977). This rock, which

has also about a hundred pecked cup-marks,

is very close to the water line and in times of

bigger flow it becomes partially submerged,

what increases its erosion.

1.4 - District of Portalegre

Like Santarém, the district of Portalegre

has only one municipality with filiform and

polissoir rock art: Nisa. In this county, the filiform rock art know so far can be observed on

59

60

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

sono concentrate in un solo comune: Nisa.

In questa regione, l'arte rupestre si può osservare sulla roccia 168A di São Simão.

Esso consiste in una serie di linee parallele molto sottili individuati da C. Chippindale nel mese di aprile del 2007, durante una

visita del X° Corso Intensivo di Arte Preistorica Europea7. Su una parete verticale di

questa roccia ci sono tre zigzag filiformi di

cronologia sconosciuta, poiché sono senza

alcuna associazione, pur essendo un motivo

che appare frequentemente in altre incisioni

attribuite a età del bronzo e dell'età del ferro.

Dal 1974, circa l'80% al 90% dell'arte rupestre della Valle del Tago è sommerso dalle

acque della diga di Fratel. In questo modo,

altre incisioni filiformi avrebbero potuto

presentarsi non essendo stato rilevate dai ricercatori dagli anni settanta, che dovevano

lavorare in fretta (a causa della diga), e il più

delle volte con la luce insufficiente per identificare i motivi filiformi.

7. Il corso è stato organizzato dal Politecnico di

Tomar.

Rock 168A of São Simão. It consists in a set of

very thin parallel lines identified by C. Chippindale in April of 2007, during a visit of the

10th Intensive Course of European Prehistoric

Art7. On a vertical part of this rock there are

three filiform zigzag of unknown chronology,

since they occur without any associations, in

spite of being a motif which appears frequently with other engravings attributed to Bronze

Age and to Iron Age.

Since 1974, about 80% to 90% of the rock

art from the Tagus valley is submerged by

the waters of the Fratel dam. This way, more

filiform engravings could have had occur, not

having been detected by the researchers from

the seventies, which had to work in a rush (because of the dam) and most of the times with

inadequate light to identify very thin motives.

7. This course was organized by the Polytechnic

Institute of Tomar

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

2. TIPOLOGIA E PARALLELI

Typology and parallels

I motivi esistenti nell'area geografica analizzata sono tipologicamente molto diversi,

come ad esempio: scalariformi, croce, zig-zag

(semplice e doppio), pentagrammi, rettangoli,

quadrati, reticoli, arbolet, figure antropomorfe

schematiche, idoli, armi (asce, pugnali, punte

di freccia, arco), "asterischi", linee parallele e

convergenti, linee parallele, "angoli", iscrizioni

pre-romane e romane, tra altre figure di definizione più difficile (Coimbra e Garcês, 2013).

Si può notare che tra i fiumi Tago e Mondego

l’ arte rupestre è soprattutto schematica, nonostante alcuni esempi "più naturalistici", ma rari,

di armi.

Al contrario, nella valle del Douro e nella Valle

del Côa, l'arte rupestre con una analoga cronologia degli esempi analizzati in questo articolo

ha molti esempi di stile naturalistico, come cavalieri, guerrieri, cavalli, cervi, cani (Baptista,

1986) tra l'altro, nonostante vari esempi di tipo

schematico e geometrico (Baptista & Reis,

2008).

Motivi come reticoli, zig-zag, pentagrammi,

scalariformi, "asterischi", crucimorfi, alberi e

punte di freccia (Tabella 1) appaiono frequentemente con una tipologia simile in paesi come

Portogallo, Spagna, Andorra, Francia e Italia,

cosa che può derivare dai contatti di popoli diversi in tarda preistoria, spiegazione che

sembra logica per l'esistenza di queste figure

in regioni che sono lontane le une dalle altre.

Altrimenti parrebbe una notevole coincidenza

che i popoli di tutti questi paesi abbiano deciso

di produrre tali motivi, contemporaneamente e

senza contatti reciproci, dal momento che alcuni dei motivi citati si possono trovare anche in

Kosovo, Grecia e Romania (Coimbra, 2013a).

The existing motives in the studied geographic area are typologically very different,

as for example: scalariform, cruciform, zigzags (simple and double), pentagrams, rectangles, squares, net-patterns, tree-like motives,

schematic anthropomorphic figures, idols,

weapons (axe, daggers, arrowheads, bow),

"asterisks", parallel and convergent lines, parallel lines, "angles", pre-Roman and Roman

inscriptions, among other of more difficult

definition (Coimbra & Garcês, 2013).

It can be noticed that between the Tagus and

Mondego rivers filiform and polissoir rock art

is mainly schematic, in spite of some “more

naturalistic” but rare examples of weapons.

On the contrary, in the Douro Valley and in

the Côa Valley, filiform rock art with a similar chronology of the examples analyzed in

this article has many examples of naturalistic

style, such as horse riders, warriors, horses,

deer, dogs (Baptista, 1986) among other, in

spite of several examples of schematic and

geometric type (Baptista & Reis, 2008).

Figures such as net-patterns, zigzag, pentagrams, scalariforms, “asterisks”, cruciforms,

tree like motifs and arrow heads (Table 1)

appear frequently with a similar typology

in countries like Portugal, Spain, Andorra,

France and Italy, what can result from contacts of different peoples in Late Prehistory, seeming to be a logical explanation for

the existence of these figures in regions that

are far from each other. Otherwise it would

have been a very big coincidence that peoples

from all of these countries decided to produce

such motives, at the same time and without

any mutual contacts, since some of the mentioned figures can also be found in Kosovo,

Greece and Romania (Coimbra, 2013a).

61

62

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

Uno dei motivi che compare più frequentemente in Europa occidentale è il pentagramma, con esempi in Portogallo (Alentejo, Beira Interior, Alto Douro), Spagna

(Extremadura, Castilla y Leon), Andorra,

Francia (Pirenei Orientali, il Monte Bego),

Italia (Liguria, Lombardia, Puglia). Esso è

presente anche in Austria e Romania.

Questa figura è rappresentata sia con una

scanalatura sottile (Fig. 7) o una scanalatura

più spessa (Fig. 8), essendo questa situazione

comune con quasi tutti i motivi esistenti di

arte rupestre filiforme e a polissoir.

▲ 7. - Pentagramma filiforme, Roccia 1 da Figueiredo

Filiform pentagram, Rock 1 from Figueiredo

One of the motives which appears more frequently in Western Europe is the pentagram,

with examples in Portugal (Alentejo, Beira

Interior, Alto Douro), Spain (Extremadura,

Castilla y Leon), Andorra, France (Eastern

Pyrenees, Mont Bego), Italy (Liguria, Lombardy, Puglia). It can also be seen in Austria

and Romania. This figure is depicted either

with a thin groove (Fig. 7) or a medium/thick

groove (Fig. 8), being this situation common

with almost all of the existing motives in filiform and polissoir rock art.

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

▲ 8.Pentagramma inciso con scanalatura spessa - Pentagram carved with a thick groove

Il reticolo è un altro dei temi più rappresentati in questo tipo di arte, che appare in

Portogallo Alentejo, Beira Interior (Fig. 9) e

Trás-os-Montes. In Spagna sono molto comuni nella regione di Extremadura, essendo presente in circa 40 rocce (Domínguez

García - Aldecoa Quintana, 2007). In

Andorra appaiono in Tossal de Cava e Encamp (Casamajor, 2008).

Al di fuori della Penisola Iberica, questo

motivo è presente, con la stessa tipologia,

in diverse rocce dei Pirenei francesi orientale (Abelanet, 1990) e dal Monte Bego

(De Lumley, 1995). In Italia, il reticolo appare nel comune di Issogne (Valle d'Aosta)

(Colella, 2005), Foppe di Nadro (Valcamonica) (Marretta, 2007), Piancogno

(Valcamonica) (Priuli, 1993), al riparo

di Cavone (Bari) (Astuti et alli, 2008), e

anche sul Monte Beigua (Savona), in Lunigiana e in Sardegna, essendo presente

anche in Kosovo, a Zatriqi (Thaqi, 2007).

Scalariformi (o motivi simili a scaletta) possono essere trovati: in Portogallo (Alentejo,

The net-pattern is another of the most depicted themes in this kind of art, appearing

in Portugal at Alentejo, Beira Interior (Fig. 9)

and Trás-os-Montes. In Spain they are very

common in the region of Extremadura, being present on about 40 rocks (DOMÍNGUEZ

GARCÍA & ALDECOA QUINTANA, 2007).

In Andorra they appear at Tossal de Cava and

Encamp (Casamajor, 2008).

Outside the Iberian Peninsula, this motif

is present, with the same typology, on several rocks from the French Eastern Pyrenees

(ABÉLANET, 1990) and from Mont Bego (DE

LUMLEY, 1995). In Italy, the net-pattern appears at Issogne (Val d’Aosta) (COLELLA,

2005), Foppe di Nadro (MARRETTA, 2007),

Piancogno (PRIULI, 1993), at the rockshelter

of Cavone (Bari) (ASTUTI et alli, 2008), and

also in Monte Beigua (Savona), Lunigiana

and Sardinia, being also present in Kosovo, at

Zatriqi (THAQI, 2007).

Scalariforms (or ladder-like motives) can

be found: in Portugal (Alentejo, Beira Interior

and Trás-os-Montes); Spain at the Province of

63

64

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

▲ 9. Reticolo (sinistra) e altre figure. Roccia 1 da Figueiredo, Portogallo.

Net-pattern (left) and other figures. Rock 1 from Figueiredo, Portugal.

Beira Interior e Trás-os-Montes); in Spagna presso la Provincia di Badajoz (Domínguez García e Aldecoa Quintana, 2007); in Andorra

(Canturri Montanya, 1974; Mas, 1977) e nella Corsica (Colella, 2005). In Italia sono presenti in Val Fredda (Trento) (Dalmeri, 2005),

nel comune di Issogne (Valle d'Aosta), (Colella, 2005) e sul Monte Beigua (Savona) (Prestipino, 2010), visto da uno di noi (F. Coimbra)

alla Roccia del Dolmen, nel 2008 e nel 2013.

Il segno zigzag appare in Portogallo (Trás-osMontes e Beira Interior), Spagna (Extremadura, Castilla y Leon), Andorra, Francia (Pirenei

Orientali, Monte Bego) e Italia (Lombardia,

Badajoz (Domínguez García & Aldecoa

Quintana, 2007), appearing also in Andorra

(Canturri Montanya, 1974; Mas, 1977)

and Corsica (Colella, 2005B). In Italy they

are present at Val Fredda (Trento) (Dalmeri, 2005) at Issogne (Val d’Aosta), (Colella,

2005) and at Monte Beigua (Savona) (Prestipino, 2010), seen by one of us (F. Coimbra) at

Roccia del Dolmen, in 2008 and in 2013.

The zigzag appears in Portugal (Trás-osMontes and Beira Interior), Spain (Extremadura, Castilla y Leon), Andorra, France

(Eastern Pyrenees, Mont Bego) and Italy

(Lombardy, Puglia), with a similar geographi-

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

Puglia), con una simile distribuzione geografica

dell’ "asterisco" (Coimbra, 2013a).

cal distribution of the “asterisk” (Coimbra,

2013A).

Alberi sono presenti in Portogallo (Trás-osMontes e Beira Interior) (Fig.10), Spagna (Castilla y Leon) (Sanchidrian, 2005), Andorra

(Canturri Montanya, 1974), Francia (Pirenei

orientali, e Monte Bego ) (Abelanet, 1990; De

Lumley, 1995), Italia (Val d'Aosta e Lombardia)

(Colella, 2005) e Grecia (Evros), questi ultimi

Tree like motives are present in Portugal (Trás-os-Montes and Beira Interior)

(Fig.10), Spain (Castilla y Leon) (Sanchidrian, 2005), Andorra (Canturri Montanya, 1974), France (Eastern Pyrenees,

Mont Bego) (Abélanet, 1990; De Lumley,

1995), Italy (Val d’Aosta and Lombardy),

▲ 10. Arbolet, purtroppo recentemente fratturato. Roccia 1 da Figueiredo

Tree like motif, unfortunately broken recently. Rock 1 from Figueiredo.

recentemente scoperti e ancora inediti8.

Punte di freccia possono essere viste nel-

(Colella, 2005) and Greece (Evros), these

last recently discovered and still unpublished8 .

8. Comunicazione personale di Giorgos Iliadis,

che sta studiando questa arte rupestre.

8. Personal information from Giorgos Iliadis,

which is studying this rock art.

65

66

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

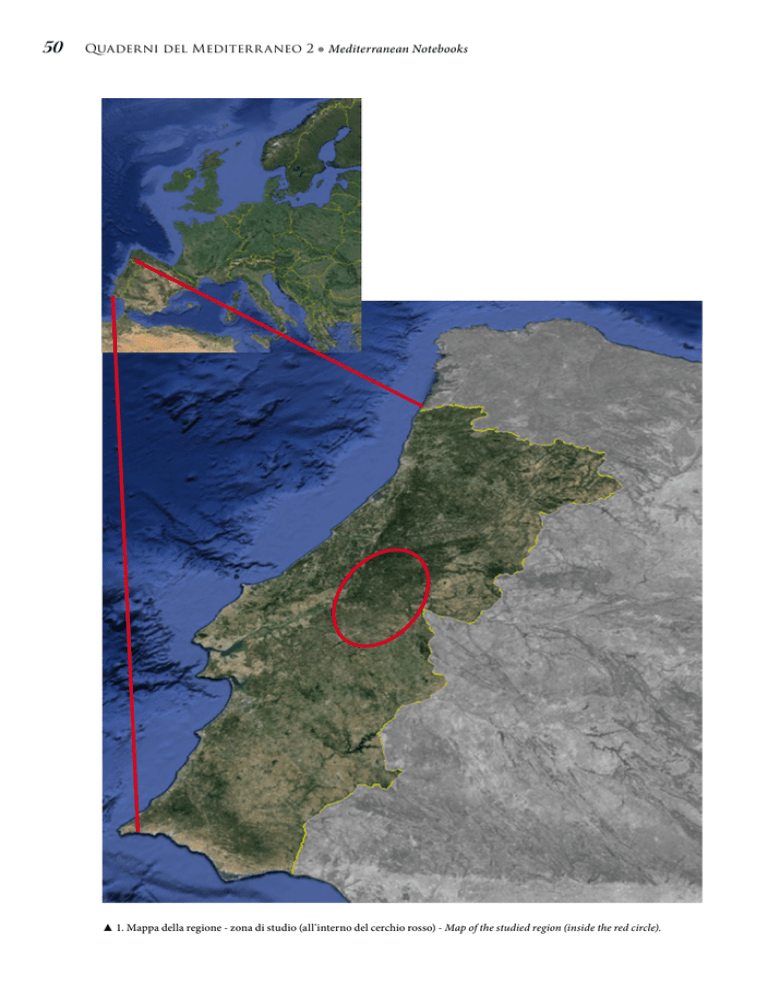

TAVOLA 1. - TABLE 1

Presenza (X) dei motivi più comuni in aree diverse (Atualizzato da Coimbra, 2013b).

Presence (x) of the most common incised motives in different areas (Updated from Coimbra, 2013b)

PO- Portogallo - Portugal; EX- Extremadura; CL- Castilla y Léon; AN- Andorra; EP- Pirinei

Orientali - Eastern Pyrenees; FA- Alpi Francesi - French Alps; CO- Corsica; LI- Liguria; VAVal d’Aosta; LO- Lombardia - Lombardy; SA- Sardegna - Sardinia; PU- Puglia; KO- Kosovo;

GR- Grecia - Greece; RO- Romania.

▲ Table 1 . Presence (x) of the most common incised motives in different areas

Presence (x) of the most common incised motives in different areas

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

le seguenti regioni e paesi: Beira Interior,

in Portogallo; Extremadura (Domínguez

García e Aldecoa Quintana, 2007) e

Castilla y Leon (Sanchidrian, 2005), in

Spagna; Andorra (Canturri Montanya,

1974); Monte Bego, in Francia (De Lumley, 1995); in Italia, in Lombardia e Puglia

(Astuti et alli, 2008). Questo motivo appare anche in paesi più lontani come la Romania (Soroceanu & Sirbu, 2012).

Figure come la "croce greca" si trovano

principalmente nella Penisola Iberica, alcuni pochi esempi in Corsica9 e Zatriqi, in

Kosovo (Thaqi, 2007). Curiosamente, questo motivo sembra non essere presente in

Francia, tranne nel caso di Corsica.

Linee parallele e convergenti appaiono in

Portogallo a Molelinhos (Cunha, 1991), a

Pedra Escrita de Ridevides, (Santos Júnior, 1963) al Prado da Rodela (Santos Júnior, 1980) e al riparo noto come Fragas do

Diabo, in Mogadouro (Lemos & Marcos,

1984). In Spagna questo motivo è molto

comune (Benito del Rey & Grande del

Brio, 1995) e in Andorra è associato ad una

leggenda popolare che dice che il demonio

furioso10, graffiò la roccia lasciando i segni

delle sue unghie (Gómez Barrera, 1992).

Oltre ad essere molto comune nella Penisola

Iberica, linee parallele e convergenti appaiono anche nei Pirenei orientali (Abelanet,

1990), Corsica, Liguria, Lombardia11, Sardegna12 e Kosovo (Thaqi, 2007).

Arrow heads can be seen in the following regions and countries: Beira Interior, in Portugal; Extremadura (Domínguez García

e Aldecoa Quintana, 2007) and Castilla

y Leon (Sanchidrian, 2005), both in Spain;

Andorra (Canturri Montanya, 1974);

Mont Bego, in France (De Lumley, 1995);

Lombardy and Puglia (Astuti et alli, 2008),

both in Italy. This motif appears also in more

distant countries like Romania (Soroceanu

& Sirbu, 2012).

Altre figure meno comuni sono anche interessanti, soprattutto per la sua rarità. È il caso,

ad esempio, di un motivo della Roccia 1 di Figueiredo, che combina técnica filiforme con

Figures like the “Greek cross” can be found

mainly in the Iberian Peninsula, existing

some few examples at Corsica9 and Zatriqi, in

Kosovo (Thaqi, 2007). Curiously, this motif

seems not being present in France except in

the case of Corsica.

Parallel and convergent lines appear in Portugal at Molelinhos (Cunha, 1991), at Pedra

Escrita de Ridevides, (Santos Júnior, 1963) at

Prado da Rodela (Santos Júnior, 1980) and

at the rockshelter known as Fragas do Diabo,

in Mogadouro (Lemos & Marcos, 1984). In

Spain this motif is very common (Benito del

Rey & Grande del Brio, 1995) and at Andorra is associated with a popular legend that says

that the devil was furious10, scratched the rock

whose grooves (the engravings) are the marks

of his nails (Gómez Barrera, 1992). Besides

being very common in the Iberian Peninsula,

parallel and convergent lines appear also in the

Eastern Pyrenees (Abelanet, 1990), Corsica,

Liguria, Lombardy11 , Sardinia12 and Kosovo

(Thaqi, 2007).

Other less common figures are also interesting, mainly by its rarity. It’s the case, for

example, of a motif from Rock 1 of Figueiredo, which combines filiform with medium

9. Comunicazione personale da M. Collella.

9. Personal information from M. Collella.

10. C'è una leggenda simile in Portogallo a Fraga

do Diabo ( LEMOS & MARCOS, 1984).

10. There’s a similar legend in Portugal at Fraga do

Diabo (LEMOS & MARCOS, 1984).

11. Osservato da F. Coimbra in queste due regioni

italiane.

11. Observed by F. Coimbra in these two Italian

regions.

12. Su una roccia dalla regione di Sassari, la cui

foto è stata gentilmente inviata da Paola Basoli,

dalla Soprintendenza di Sassari.

12. On a rock from the region of Sassari, whose

photo was kindly sent by Paola Basoli, from the

Soprintendenza di Sassari.

67

68

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

polissoir, che sembra essere stato fatto in

due momenti differenti. Deve essere stato

prima un reticolo, poi una maniglia è stata aggiunta in seguito, costituendo quindi

una sorta di paletta, con una eventuale rilettura del motivo (Fig. 11).

grooves, seeming to have been done in two

different moments. It must have been first a

net-pattern, to which a handle was added later, constituting then a kind of palette, after a

possible reinterpretation of the motif (Fig. 11).

▲ 11. Palette (?) costituita da un reticolo filiforme e un manico più spesso (aggiunto dopo?). Rilievo: Sara Garcês.

Palette (?) constituted by a filiform net-pattern and a thicker handle (added later?). Tracing: Sara Garcês

Un altro curioso caso di rarità nella

stessa roccia è una iscrizione pre romana

che ha la particolarità di avere una svastica come lettera (Fig.12), ciò che è veramente unico in questa parte del mondo e

con questa cronologia13.

Another curious case of rarity in the same

rock is a pre Roman inscription which has the

particularity of having a swastika as a letter

(Fig.12), what is very unique in this part of the

world and with this chronology 13.

13. La svastica con bracci curvi è stato utilizzato

come una lettera nella Creta minoica, circa nel

1800 aC. La svastica con braccio destro ad angolo

è una lettera dell'alfabeto cirillico, nel IX° secolo

dC (Batata, Coimbra & Gaspar, 2004).

13. The swastika with curved arms was used

as a letter in Minoan Crete, about 1800 BC. The

swastika with right angled arms was a letter

of the Cyrillic alphabet, in the 9th century AD

(Batata, Coimbra & Gaspar, 2004).

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

▲ 12. Iscrizione preromana con una svastica come lettera. Rilievo: F. Coimbra

Pre Roman inscription with a swastika as a letter. Tracing: F. Coimbra

Ancora sulla Roccia 1 da Figueiredo,

una tipica ascia del Bronzo senza impugnatura, scolpita con scanalature a polissoir (Fig.15), costituisce un esempio importante per la cronologia delle incisioni

che presentano una patina simile.

Still on Rock 1 from Figueiredo, a typical

Bronze Age axe without handle, carved with

medium/thick grooves (Fig.15), constitutes an

important example for the chronology of the engravings which present a similar patina.

69

70

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

3. CRONOLOGIA

Cronology

La mancanza di studi sistematici sull’arte

rupestre post-paleolitica filiforme e a polissoir in Portogallo rende difficile stabilire la

cronologia di alcune incisioni, sopratutto

quando non ci sono associazioni con altri

motivi di una datazione più sicura.

Tuttavia, alcuni paralleli provenienti da

altre regioni possono aiutare a comprendere

meglio questa problematica. E' il caso di numerose grotte di Castilla y Leon (Spagna),

che hanno sulle loro pareti motivi come

punte di freccia, reticoli, zig-zag, scalariformi, che appaiono anche in rocce all'aperto

dalla zona studiata in questo articolo. Gli

scavi archeologici effettuati in quelle grotte

rivelato contesti datati da circa il 3000 a C

al 1500 a C., essendo le incisioni, secondo

JL Sanchidrián (2005), probabilmente dallo

stesso periodo. Così, sembra che al centro

della Penisola Iberica ci siano esempi di arte

rupestre filiforme e a polissoir dal III e II

millennio a C.

Curiosamente, le incisioni a zigzag e a reticoli possono essere viste su tavolette di argilla provenienti da diversi insediamenti del

Calcolitico della Penisola Iberica (COIMBRA, 2013a), come Vila Nova de São Pedro,

nel centro del Portogallo (Fig. 13).

Poi, una domanda deve essere fatta: se queste figure appaiono scolpite su ceramica con

una cronologia riferita al Calcolitico, perché

non possono essere stati prodotti anche su

superfici rocciose nello stesso periodo?

In realtà, nell'arte rupestre dalla penisola

iberica ci sono rappresentazioni a polissoir

di armi dell'età del bronzo, come le alabarde

da Peña Raya (Cáceres, Spagna) (SEVILLANO, 1991) e da Rocha Escrita de Ridevides,

nel nord del Portogallo (fig. 14).

The lack of systematic studies about Post-Palaeolithic filiform and polissoir rock art in Portugal makes difficult to establish the chronology of

some engravings, namely when there aren’t any

associations with other motives of a more secure

dating.

However, some parallels from other regions

can help to understand better this problematic.

It’s the case of several caves from Castilla y Leon

(Spain), that have on their walls motives such as

arrow heads, net-patterns, zigzag, scalariforms,

which appear also in open air sites from the area

studied in this article. Archaeological excavations carried out in those caves revealed contexts

from about 3000 BC to 1500 BC., being the engravings, according to J. L. Sanchidrián (2005),

probably from the same period. Thus, it seems

that in the centre of the Iberian Peninsula there

are examples of filiform and polissoir rock art

from the III and the II millennium BC.

Curiously, motives like zigzag and net patterns can be seen carved on clay tablets from several Calcolithic settlements of the Iberian Peninsula (COIMBRA, 2013a), like Vila Nova de São

Pedro, in the centre of Portugal (Fig. 13).

Then, a question must be made: if these motives appear carved on pottery with a Calcolithic

chronology, why can’t they have been produced

also over rock surfaces during the same period?

In fact, in the rock art from the Iberian Peninsula there are representations of Bronze Age

weapons, such as the halberds from Peña Rayá

(Cáceres, Spain) (Sevillano, 1991) and from

Rocha Escrita de Ridevides, in the North of Portugal (Fig. 14).

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

▲ 13. Tavolette di argila com zigzag e reticoli (Da Paço & Jalhay, 1971)

Clay tablets with zigzag and net-patterns. (After Paço & Jalhay, 1971)

▲ 14. Alabarda della Rocha Escrita de Ridevides (in centro)

Halberd from Rocha Escrita de Ridevides (in the center).

71

72

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

Questi esempi, tra gli altri, contraddicono

l'idea di alcuni ricercatori che l’arte rupestre

filiforme e a polissoir è stata effettuata in periodi storici. Ad esempio, N. Bianchi (2010b)

ha pubblicato le immagini di punte di lancia

di bronzo, incise su superfici rocciose del

Monte Bego, dimostrando in questo modo

che ci sono incisioni filiformi in questo settore molto prima dei tempi storici.

Per quanto riguarda le altre regioni, come

Piancogno (Valcamonica, Italia), ci sono

diverse incisioni filiformi coperti da motivi databili, che attribuiscono almeno una

cronologia protostorica a quel tipo di motivi

(Priuli, 1991). Nella stessa valle, ma a Campanine di Cimbergo, un reticolo filiforme è

coperto da una impronta di piedi protohistorica a martellina14 sulla Roccia 61 (Rossi,

Zanetta, 2009: 231).

Una prospezione archeologica effettuata nel corso del 2001 lungo la riva sinistra

del fiume Ocreza (un affluente del Tago) ha

permesso l'identificazione delle rocce con

tracce filiformi, essendo alcune di queste

incisioni sovrapposte da figure a martellina.

Secondo L. Oosterbeek (2003a), alcuni di

questi motivi filiformi possono, infine, risalire al Neolitico.

Nuove scoperte di arte rupestre filiforme

e a polissoir nella penisola iberica, purtroppo alcune delle quali non ancora publicate,

dimostrano che c'è ancora molto lavoro da

fare per quanto riguarda la cronologia di

questo tipo di arte. Tuttavia, gli esempi che

esistono tra il Mondego e il fiume Tago possono essere datati, in via preliminare, in un

periodo che va dal tardo Neolitico/ Calcolitico iniziale fino all'Età del Ferro, con una

concentrazione maggiore di motivi a partire

dalla metà del II millennio a C.

14. Nel Ocreza, come a Monte Bego, ci sono

incisioni filiformi coperte da motivi a martellina e

viceversa.

These examples, among others, contradict the

idea of some researchers that filiform and polissoir rock art was made in historical periods. For

example, N. Bianchi (2010b) published images

of spear heads from Bronze Age, carved on rock

surfaces from Mont Bego, proving this way that

there are filiform engravings in this area much

before historical times.

Regarding other regions, like Piancogno

(Valcamonica, Italy), there are several filiform

engravings covered by datable motives, which

attribute at least a protohistoric chronology to

that kind of figures (PRIULI, 1991). In the same

valley, but at Campanine di Cimbergo, a filiform

net-pattern is covered by a protohistoric pecked

footprint14, on Rock 61 (Rossi; Zanetta, 2009:

231).

Archaeological prospection carried out during

2001 in the left bank of the River Ocreza (a tributary of the Tagus) allowed identifying some rocks

with filiform traces, being some of these engravings overlapped by pecked figures . According

to L. Oosterbeek (2003a), some of these filiform

motives may, eventually, date from the Neolithic.

Constant new discoveries of filiform and polissoir rock art in the Iberian Peninsula, unfortunately some of them still unpublished, show that

there’s still a lot a work to do regarding the chronology of this kind of art. However, the examples

that exist between the Mondego and the Tagus

rivers can be dated, in a preliminary way, in a

period from the Late Neolithic/Early Calcolithic

till the end of Iron Age, with a bigger concentration of motives starting in the middle of the II

millennium BC.

14. In the Ocreza, like in Mont Bego, there are

filiform engravings covered by pecked motives

and vice-versa.

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

5. CONCLUSIONI

Final Statements

Trent’anni fa, quando l’arte rupestre filiforme portoghese era quasi una materia

sconosciuta, VO Jorge (1983), molto saggiamente, la considerò come una manifestazione artistica autonoma, evidenziando

notevoli differenze tipologiche riguardanti

gli altri gruppi tematici dalla penisola iberica. In effetti, questo tipo di arte non ha

nulla a che fare con gli altri gruppi di arte

rupestre della zona citata, ma, nonostante le

distanze geografiche, deve essere analizzata

insieme con i paralleli che esistono in diverse regioni di Portogallo, Spagna, Andorra, a

sud di Francia e Nord Italia. La somiglianza

strutturale di una vasta gamma di motivi

che possono essere visti in tutti questi paesi

permette di pensare nell'esistenza di contatti culturali tra alcune di queste regioni almeno durante l’ Età del Bronzo e del Ferro

(Coimbra, 2010). E’ un'ipotesi che ha più

senso di quella di una creazione simultanea,

in ciascuno di questi paesi, di figure come

scalariformi, zig-zag, reticoli, pentagrammi

e altri. Per quanto riguarda questa proposta

va detto che ci sono testimonianze archeologiche di contatti, durante il III millennio

a C, tra regioni lontane come la spagnola

Andalusia e l’italiana Liguria, dove recentemente sono stati trovati esemplari di ceramica da Los Millares15.

Al fine di stabilire una cronologia più accurata per l’arte rupestre sarebbe importante creare inventari regionali che potrebbero

Thirty years ago, when Portuguese filiform

rock art was almost an unknown subject, V.

O. Jorge (1983), very wisely, considered it as

an autonomous artistic manifestation, showing significant typological differences regarding the other thematic groups from the Iberian Peninsula. Indeed, this kind of art has

nothing to do with the other rock art groups

from the mentioned area but, despite geographical distances, it must be analysed together with the parallels which exist in several

regions from Portugal, Spain, Andorra, South

of France and North of Italy. The structural

similarity of a wide range of motives that can

be seen in all the referred countries allows

thinking in the existence of cultural contacts

between some of those regions at least during

Bronze Age and Iron Age (Coimbra, 2010).

It’s an idea that makes more sense than the

simultaneous creation, in each of those countries, of figures such as scalariforms, zigzags,

net-patterns, pentagrams and others. Regarding this proposal it must be said that there are

archaeological evidences of contacts, during

the III millennium BC, between distant regions such as Spanish Andalusia and Italian

Liguria, where recently were found examples

of pottery from Los Millares15.

In order to establish a more accurate chronology for filiform and polissoir rock art it

would be important to create regional inventories that could be accessed by researchers

from different countries. In a word, it’s a mat-

15. Secondo diverse immagini presentate da

Filippo Gambari al Congresso L'arte rupestre

delle Alpi , organizzato nel 2010 dal Centro

Camuno di Studi Preistorici . Per quanto riguarda

gli altri contatti tra il Nord Italia e il Centro e Nord

del Portogallo durante il I° millennio aC, vedere

Coimbra , 2005, 151.

15. According to several images presented by

Filipo Gambari in the Congress L’arte rupestre

delle Alpi, organized in 2010 by Centro Camuno

di Studi Preistorici. Regarding other contacts

between the North of Italy and the Centre and

North of Portugal during the I millennium bC, see

Coimbra, 2005, 151

73

74

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

essere accessibili da ricercatori provenienti

da diversi paesi. In una parola, è una questione di un network internazionale, che ha

cominciato a svilupparsi durante la sessione

Post-Palaeolithic filiform rock art in Western Europe, coordinata da F. Coimbra e

U. Sansoni nel settembre di 2014, durante

il XVII Convegno UISPP a Burgos, Spagna

(Coimbra, in stampa; Coimbra & Garcês,

in stampa).

ter of an international network, which started

to develop during the session Post-Palaeolithic

filiform rock art in Western Europe, coordinated by one of us (F. Coimbra) and Umberto

Sansoni in September of 2014 during the XVII

IUPPS Congress at Burgos, Spain (Coimbra,

in press; Coimbra & Garcês, in press).

Repliche materiali possono essere profittevolmente utilizzate nei musei, dal momento

We cannot finish this article without making some remarks regarding the rock art conservation in the studied area. For example,

Rock 1 from Figueiredo presents some areas

which are much eroded being present the danger of loss of important engravings in a near

future. This rock is placed on a mountain

about 900m above sea level. During winter,

the water on the cracks around an engraving

that depicts a Bronze Age axe (Fig.15) usually

freezes, becoming ice, which enlarges the same

cracks, destroying slowly the rock surface.

Indeed, in a general way, rock art is fragile and in the next decades several carvings

will disappear forever if adequate preventive

measures will not be taken. For the region

between the Tagus and the Mondego, it will

be indispensable to make some replicas of the

most important rocks16 , using 3D laser scanner, because they will allow having in 30, 50,

80 or more years a replica of the engravings

with the level of conservation that they present today. These replicas can be material

(made in silicone) or virtual (stored in external hard disks). Material replicas can be rentable, being used in museums, since frequently

the rock art sites are located in places of difficult access to the general public. Virtual replicas can be transformed into material, if the

original engravings are much eroded or have

been destroyed.

The process of 3D laser scanning will be a

way of stopping the natural weathering to

which any open air carved rock is subjected,

16. Oltre gli agenti atmosferici, gli incendi boschivi

sono una delle minacce più pericolose per l'arte

rupestre. Per questo è necessario fare repliche

non solo delle incisioni più erose, ma anche delle

rocce più importanti.

16. Besides weathering, forest fires are one of

the more dangerous menaces to rock art. This

way it’s necessary to make replicas not only of

the more eroded engravings but also of the more

important rocks.

Non possiamo finire questo articolo senza fare alcune osservazioni per quanto riguarda la conservazione dell’arte rupestre

nell'area studiata. Ad esempio, Roccia 1 da

Figueiredo presenta alcune aree che sono

molto erose con la possibilità di perdita di

incisioni importanti in un prossimo futuro.

Questa roccia è posta su una montagna a

circa 900 metri sopra il livello del mare. Durante l'inverno, l'acqua si blocca sulle fessure intorno un'incisione che raffigura un

ascia dell’ Età del Bronzo (Fig.15) diventando ghiaccio, che ingrandisce le stesse crepe,

distruggendo lentamente la superficie della

roccia.

Infatti, in generale, l'arte rupestre è fragile

e nei prossimi decenni diverse incisioni spariranno per sempre se non verranno prese

adeguate misure preventive. Per la regione

tra il Tago e il Mondego, sarà indispensabile

fare alcune repliche delle rocce più importanti16, utilizzando scanner laser 3D, perché

questa tecnologia permette di avere in 30,

50, 80 o più anni una replica delle incisioni con il livello di conservazione che essi

presentano oggi. Queste repliche possono

essere materiali (in silicone) o virtuale (memorizzati in hard disk esterni).

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

▲ 15. Area erosa nella Roccia 1 da Figueiredo, vicina una rara rapresentazione d’ascia dell’età del Bronzo

Eroded area on Rock 1 from Figueiredo, near a rare depiction of a Bronze Age axe.

75

76

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

che i siti di arte rupestre sono spesso situati

in luoghi di difficile accesso al pubblico. Repliche virtuali possono essere trasformate

in materiale, se le incisioni originali sono

molto erose o sono state distrutte.

Il processo di scansione laser 3D sarà un

modo di fermare il degrado naturale a cui

ogni roccia incisa all'aria aperta è sottoposta, essendo una misura molto importante

di archeologia preventiva. Sarà anche la elaborazione di un database di incisioni rupestri come un lascito ai posteri (Coimbra,

2011b).

Diverse incisioni sono estremamente importanti e di solito presentano problemi di

conservazione, la loro scansione laser 3D è

l'unico modo sicuro per evitare la loro perdita per sempre. I ricercatori di arte rupestre

del XXI secolo hanno il compito urgente di

preservare per i figli dei figli dei loro figli il

patrimonio culturale inciso sulle rocce dai

loro lontani antenati.

being a very important measure of preventive

archaeology. It will also constitute a rock art

database and a legacy to posterity (Coimbra,

2011b).

Since several engravings are extremely

important and usually they present problems

of conservation, their 3D laser scanning it’s

the only safe way to avoid their loss for ever.

The rock art researchers from the 21st century

have the urgent task of preserving for their

children’s children’s children the cultural

heritage carved on the rocks by some of their

remote ancestors.

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

BIBLIOGRAFIA - Bibliografy

Abélanet, J. (1990) - Les roches gravées nord catalanes. Terra Nostra, nº5. Centre d’Etudes

Préhistoriques Catalanes. Université de Perpignan, Prada: 101-209.

Astuti, P.; Colombo, M.; Cremonesi, R.g.; Serradimigni, M.; Usala, M. (2008) - Incisioni rupestri dal Riparo del Cavone (Spinazzola, Bari). Bulletino di Paletnologia Italiana,

97. Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico L. Pigorini, Roma: 121-147.

Baptista, A. M. (1986) - Arte rupestre pós-glaciária. Esquematismo e abstracção. História

da Arte em Portugal, I. Alfa, Lisboa: 52-55.

Baptista, A. M.; Reis, M. (2008) - Prospecção da Arte Rupestre na Foz do Côa. Da iconografia do Paleolítico superior à do nosso tempo, com passagem pela IIª Idade do Ferro.

Actas do III Congresso de Arqueologia de Trás-os-Montes, Alto Douro e Beira Interior.

Associação Cultural Desportiva e Recreativa de Freixo de Numão, Porto: 62-95.

Barros, A. M; Nunes, J. de C.; Pereira, A. N. (1959) - A Pedra Letreira. Memórias Arqueológicas do Concelho de Góis. Câmara Municipal de Góis: 9-37.

Batata, C. (1997) - A Sertã na transição entre a Pré-história recente e a Proto-história.

Estudos Pré-históricos, V. Centro de Estudos Pré-históricos da Beira Alta, Viseu: 163-167.

Batata, C. (2006) - Idade do Ferro e romanização entre os rios Zêzere, Tejo e Ocreza. Trabalhos de Arqueologia, 46. Instituto Português de Arqueologia, Lisboa.

Batata, C.; Coimbra, F. A (2005) - Laje da Fechadura: arte rupestre filiforme, in 25 sítios

arqueológicos da Beira Interior. ARA/ Câmara Municipal de Trancoso: 42-43.

Batata, C., Coimbra, F. A.; Gaspar, F. (2004) - As gravuras rupestres da Laje da Fechadura (Concelho da Sertã). Revista de Portugal, Nova Série, n.º 1. Solar Condes de Resende,

V. N. de Gaia: 26-31.

Batata, C.; Gaspar, F. (2000) - Arte rupestre da bacia hidrográfica do rio Zêzere.

Actas do III Congresso de Arqueologia Peninsular, Vol.4. Adecap, Porto: 575-581.

Batata, C.; Gaspar, F. (2011) - Carta Arqueológica do Concelho de Pampilhosa da Serra.

Câmara Municipal da Pampilhosa da Serra/OZECARUS, Pampilhosa da Serra.

Benito del Rey L.; Grande Del Brio R. (1995) - Petroglifos prehistóricos en la comarca

de las Hurdes (Cáceres). Simbolismo e Interpretación. Librería Cervantes, Salamanca: 7-89.

Bianchi, N. (2010a) - Mount Bego prehistoric rock carvings. Adoranten 2010. Scandinavian Society for prehistoric Art. Tanum: 70-80.

Bianchi, N. (2010b) - Monte Bego: Contesto cronologico e culturale. Convegno Internazionale L’arte rupestre delle Alpi. Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici, Capo di Ponte: 32-35.

77

78

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

Calado, M.; Rocha, L.; Santos, I.; Pimenta, A. (2008) - Rock art in context: Late Bronze

Age motifs in Monsaraz (Alentejo, Portugal). III Taller Internacional de Arte Rupestre,

Havana: 119-136.

Caninas, J.; Henriques, F.; Batata, C.; Batista, A. (2004) - Novos dados sobre a Pré-História Recente da Beira Interior Sul. Megalitismo e Arte Rupestre no Concelho de Oleiros.

Estudos Castelo Branco, Nova Série, 3. AEAT, Castelo Branco: 1-24.

Canturri Montanya, P. (1974) - Els Gravats Rupestres Esquematics de les Valls d’Andorra. Actas del Septimo Congresso Internacional de Estudios Pirenaicos, Tomo I. IEP/CSIC,

Jaca: 81-87.

Casamajor I Esteban, J. (2008) - Els Gravats Rupestres del Tossal de Cava (Alt Urgell) i un

estel solitari a Montalarí (Encamp). Papers de Recerca Histórica, 5. Societat Andorrana de

Ciències, Andorra: 9-25.

Coimbra, F.a. (2005) - O pentagrama de Ribeira de Piscos (V.N. de Foz Côa) e seus paralelos no contexto da arte rupestre filiforme pós-paleolítica da Península Ibérica. Actas do I

Congresso de Arqueologia de Trás-os-Montes, Alto Douro e Beira Interior. Côavisão,7. V.N.

de Foz Côa: 145-157.

Coimbra, F.a. (2008a) - The pentagram in rock art: some interpretive possibilities.

In, Symbolism in Rock Art. COIMBRA, F.A.; Dubal, L. (eds.). XV IUPPS Proceedings. Archaeopress, Oxford: 7-12.

Coimbra, F.a. (2008b) - Portuguese rock art in a Protohistoric context. ARKEOS, 24. Centro Europeu de Investigação da Pré-história do Alto Ribatejo, Tomar: 111-130.

Coimbra, F.a. (2008c) - Conservation and destruction of rock art in Portugal: some case

studies. In Rock Art World Main Problems. Man In India, 88 (2-3). Serials Publications.

New Dehli: 223-240.

Coimbra, F.a. (2010) - Possible Late Prehistoric contacts between the Alps and the Iberian

Peninsula analyzed through rock art examples and archaeological evidence. Convegno Internazionale L’arte rupestre delle Alpi. Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici, Capo di Ponte:

48-51.

Coimbra, F.a. (2011a) - The symbolism of the pentagram in west European Rock Art: a

semiotic approach. In, Art and Communication in pre literate societies. XXIV Valcamonica

Symposium. CCSP/UNESCO, Capo di Ponte: 122-129.

Coimbra, F.a. (2011b) - Para os nossos bisnetos … Arqueologia Preventiva e Arte Rupestre.

In Patrimônio Cultural Arqueológico: Diálogos, reflexões e práticas. BASTOS, R.L.; SOUZA,

M.C. (Eds.). IPHAN, São Paulo: 164-173.

Coimbra, F.a. (2013a) - Common themes and regional identities in European Late Prehistoric filiform rock art. XXV Valcamonica Symposium. Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici, Capo di Ponte.

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

Coimbra, F.a (2013B) - Ruptejo: Arqueologia Rupestre da Bacia do Tejo.

Arte Rupestre da Idade do Bronze e da Idade do Ferro na Bacia Hidrográfica do Médio/Alto

Tejo Português. Síntese descritiva. Arkeos 35. Ceiphar, Tomar: 163pp.

Coimbra, F. A. (In press) - Late prehistoric incised rock art in southern Europe: a contribution for its typology. In Coimbra, F. A.; Sansoni, U. (eds) Post-Palaeolithic filiform rock

art in Western Europe. Proceedings of the XVII IUPPS Conference, Burgos

Coimbra, F.a.; Garcês, S. (2010) - Arte Rupestre do Pinhal Interior. Exposição Itinerante.

Instituto Politécnico de Tomar/Museu de Arte Pré-Histórica e do Sagrado no Vale do Tejo,

s/l: 1-24.

Coimbra, F.a.; Garcês, S. (2013) - Arte rupestre incisa entre o Tejo e o Zêzere: contributo

para o seu inventário, tipologia e datação. ARKEOS, 34. Atas do Congresso de Arqueologia

do Alto Ribatejo. Ceiphar, Tomar: 243-254.

Coimbra, F. A.; Garcês, S. (In press) - The rock art from Figueiredo (Sertã, Portugal):

typology, chronology and interpretation. In Coimbra, F. A.; Sansoni, U. (eds) Post-Palaeolithic filiform rock art in Western Europe. Proceedings of the XVII IUPPS Conference,

Burgos

Colella, M. (2005) - I Graffiti del Lago Couvert. Pre-Atti del IV Convegno di Studi sull’arte schematica non figurativa nelle Alpi. Dipartimento Valcamonica del Centro Camuno di

Studi Preistorici. Saviore del Adamello.

Cunha, A. M. L. da (1991) - Estação de Arte Rupestre de Molelinhos. Notícia Preliminar.

Câmara Municipal de Tondela: 1-13.

Dalmeri, G. (2005) - Incisioni rupestri in Val Fredda sull’Altopiano di Folgaria (Trento).

Nota preliminare. Studi Trent. Sci. Nat. Preistoria Alpina, 40. Museo Tridentino di Scienze

Naturali, Trento: 83-87.

De Lumley, H. (1995) - Le grandiose et le sacré. Gravures rupestres Protohistoriques et

historiques de la région du Mont Bego. Édisud, Aix-en-Provence: 368-375.

Domínguez García, A.; Aldecoa Quintana, M. A. (2007) - Corpus de Arte Rupestre en

Extremadura, Vol. II. Arte Rupestre en La Zepa de La Serena. In COLLADO GIRALDO;

GARCÍA ARRANZ (Eds). Junta de Extremadura, Mérida.

Gomez Barrera, J. A. (1992) - Grabados rupestres postpaleolíticos del Alto Duero. Museo

Numantino/Caja Salamanca y Soria, Soria.

Henriques, F.; Caninas, J. C. (2009) - Pedra das Letras: uma rocha com grafismos lineares

(Proença-a-Nova). Açafa On-line, 2. AEAT: 1-18.

Isetti, G. (1957) - Le incisioni di Monte Bego a técnica linerae. Rivista di Studi Liguri,

XXIII (3-4). Istituto Internazionale di Studi Liguri, Bordighera: 163-196.

79

80

Quaderni del Mediterr aneo 2 ◉ Mediterranean Notebooks

Jorge, V. O. (1983) - Gravuras portuguesas, Zephyrus, XXXVI. Universidad de Salamanca:

53-61.

Jorge, V. O.; Jorge, S. O. (1995) - Portuguese rock art: a general view, Trabalhos de Antropologia e Etnologia, 35. SPAE, Porto: 341-343.

Lemos, F. S.; Marcos, D. (1984) - As gravuras rupestres das Fragas do Diabo (Mogadouro).

Cadernos de Arqueologia, série II, Vol.I. UAUM, Braga: 137-142.

Marretta, A. (2007) - L’arte rupestre di Nadro (Ceto): le Foppe. In, La Riserva Naturale

Incisioni Rupestri di Ceto, Cimbergo, Paspardo. CCSP, Capo di Ponte: 42-69.

Mas, D. (1977) - El Roc de les Bruixes. Noves aportacions als gravats rupestres andorrans.

Quaderns d’ Estudis Andorrans, 2. Cercle de les Arts i de les Lletres de les Valls d’ Andorra,

Escaldes: 5-31.

Monteiro, J. P.; Gomes, M. V. (1974-1977) - Rocha com covinhas na Ribeira do Pracana. O

Arqueólogo Português, série III, VII a IX. Secretaria de Estado da Cultura/Direção Geral

do Património Cultural, Lisboa: 95-99. Oosterbeek, L. (2003) - Vale do Ocreza - Campanha 2001. Techne, 8. Arqueojovem, Tomar: 41-70.

Oosterbeek, L.; Cardoso, D. (2004) - Vale do Ocreza. Prospecção e levantamentos. Techne, 9. Arqueojovem, Tomar: 65-88.

Paço, A. Do; Jalhay, E. (1971) - El Castro de Vilanova de San Pedro. In, Trabalhos de

Arqueologia de Afonso do Paço, vol. II. Associação dos Arqueólogos Portugueses, Lisboa:

183-266.

Prestipino, C. (2010) - L’Arte rupestre nella Provincia di Savona: lo stato della ricerca.

Convegno Internazionale L’arte rupestre delle Alpi. Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici,

Capo di Ponte: 120-123.

Priuli, A. (1991) - Stelliformi. In, La cultura figurativa preistorica e di tradizione in Italia.

Edizione Giotto, Bologna: 182-187.

Priuli, A. (1993) - I Graffiti Rupestri di Piancogno. Le incisioni di età celtica e romana in

Vallecamonica. Società Editrice Vallecamonica, Darfo Boario Terme: 71-73; 118-121.

Rosi, M.; Maja, A. (1973) - Le pietre incise di Monte Beigua presso Sassello (Savona). Bollettino del Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici, Vol.X. CCSP, Capo di Ponte: 145-157.

Rossi, G.; Zanetta, M. (2009) - Le rocce istoriate: corpus e schede. In Lucus Rupestris.

Sei milleni d’arte rupestre a Campanine di Cimbergo. SANSONI, U.; GAVALDO, S. (Eds.).

CCSP, Capo di Ponte: 227-233.

Le due missioni a Filippi (anni 2005-2006) ◉ The two missions in Philippi (years 2005-2006)

Sanchidrián, J. L. (2005) - Manual de Arte Prehistórico. (2ª ed.). Ariel, Barcelona: 495-504.

Santos Junior, J. R. (1963) - As gravuras litotrípticas de Ridevides (Vilariça). Trabalhos

de Antropologia e Etnologia, XIX. SPAE, Porto: 111-144.

Santos Junior, J. R. (1980) - As gravuras rupestres da fonte do Prado da Rodela (Meirinhos, Mogadouro). Trabalhos de Antropologia e Etnologia, XXIII. SPAE, Porto: 594-599.

Seglie, D. (1982) - Monte Bego. Arte schematica linerae, convergenze formali e cronologie.

Archeologia, 10-11. Anno VII-VIII. Gruppo Archeologico Vercellese, Vercelli: 32-43.

Sevillano San José, M. C. (1983) - Analogias y diferencias entre el arte rupestre de las

Hurdes y el Valle del Tajo, Zephyrus, XXXVI. Universidad de Salamanca: 259-263.

Sevillano San José, M. C. (1991) - Grabados rupestres en la comarca de Las Hurdes

(Cáceres). Acta Salmanticensia, 77. Universidad de Salamanca: 9-216.

Sevillano San José, M. C.; Bécares Pérez, J. (1997) - Grabados rupestres de la la comarca

de Las Hurdes. Extremadura Arqueológica VII. Jornadas sobre arte rupestre en Extremadura. Junta de Extremadura/ Universidad de Extremadura, Cáceres: 73-92.

Sevillano San José, M. C.; Bécares Pérez, J. (1998) - Grabados Rupestres en La Huerta

(Caminomorisco, Cáceres). Zephyrus LI. Universidad de Salamanca: 289-302.

Soroceanu, T; Sirbu, V. (2012) - La grotte de Nucu du Néolithique à l’âge du Bronze.

In, Un Monument des Carpates Orientales avec des représentations de la Préhistoire et du

Moyen Âge - Nucu « Fundu Pesterii », Département de Buzau. Sirbu, V. ; MATEI, S. (eds.).

Muzeul Brailei/Istros, Buzau : 119-336.

Thaqi, I. (2007) - Kosova rock art. Interpretation and Decodification. In, Rock Art in the

frame of the Cultural Heritage of Mankind. XXII Valcamonica Symposium. CCSP/UNESCO, Capo di Ponte: 493-501.

Ventura, S. (1996) - Datazione delle figure a “stella” nell’ arte rupestre camuna.

B. C. NOTIZIE. Notiziario del Centro Camuno di Studi Preistorici, CCSP, Capo di Ponte:

9-11.

81