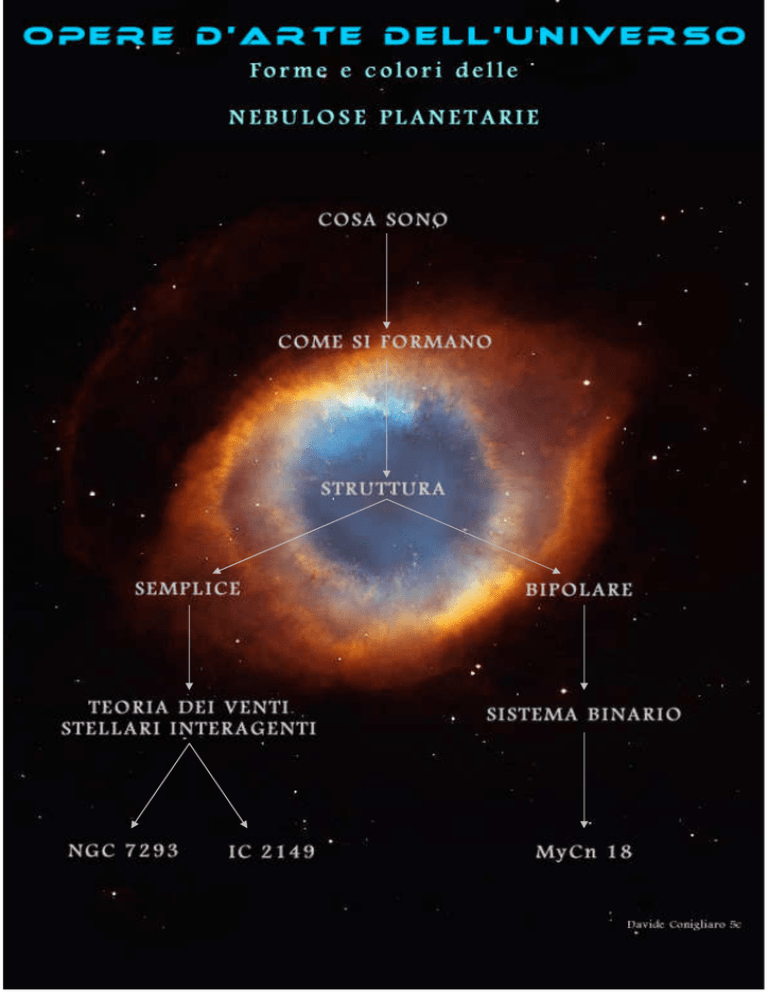

OPERE D’ARTE

DELL’UNIVERSO

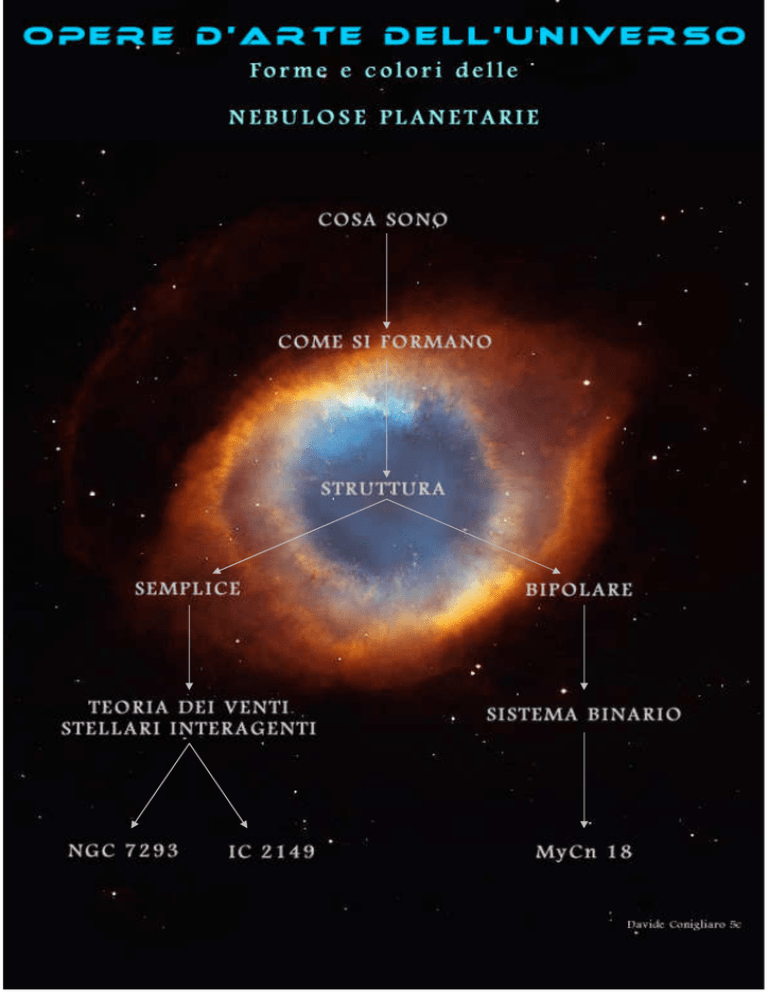

Forme e colori delle nebulose planetarie

Nebulose Planetarie

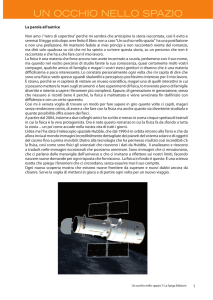

Il termine “Nebulosa Planetaria” risale a due secoli fa, e si deve a un’interpretazione errata

dell’astronomo inglese William Herschel. La forma vagamente tondeggiante di molte di queste

strutture ricordò a Herschel il disco verdastro di Urano(di cui era stato lo scopritore) e lo portò a

pensare che si trattasse di sistemi planetari, che prendevano forma attorno a giovani stelle. Il nome

rimase, anche se si scoprì, che era vero il contrario: questo tipo di nebulosa è costituita dal gas

espulso da una stella morente, e non rappresenta il passato, ma il futuro. Tra cinque miliardi di anni,

o giù di li anche il Sole concluderà la sua esistenza cosmica nell’elegante violenza di una nebulosa

planetaria.

Come tutte le grandi espressioni artistiche, le nebulose planetarie non si limitano ad

affascinarci, ma ci costringono anche a mettere in dubbio la nostra percezione del mondo. Nel caso

specifico, sfidando la teoria dell’evoluzione stellare, il modello che descrive l’arco vitale della vita

delle stelle. Questa teoria è un ramo maturo della scienza, uno dei fenomeni su cui si basa tutta la

comprensione del cosmo, ma non riesce a spiegare le complesse figure che compaiono nelle

immagini di Hubble. Se le stelle nascono sferiche, vivono sferiche e muoiono sferiche, come fanno

a disegnare strutture così elaborate da somigliare a una formica, a una stella marina o all’occhio di

un gatto?

Giganti rosse e nane bianche

Nell’ultimo secolo gli astronomi hanno compreso che al momento della loro morte le stelle

si dividono in due classi distinte. Quelle che appartengono all’elite delle stelle massicce –

dimensioni superiori a otto masse solari – esplodono improvvisamente come supernove. Le stelle

più piccole come il Sole, muoiono lentamente e, anziché detonare, consumano l’ultima fase della

loro esistenza bruciando spasmodicamente il loro combustibile nucleare, un pò come un motore

d’automobile che sta finendo la benzina.

Le reazioni nucleari nel cuore delle stelle di questa ultima classe, reazioni che le hanno

alimentate per quasi tutta la vita, esauriscono tutto l’idrogeno disponibile, poi l’elio. Man mano che

la reazione nucleare si sposta all’esterno, verso il materiale fresco del guscio che circonda il nucleo,

la stella si gonfia, fino a diventare una “gigante rossa”. Quando si esaurisce anche l’idrogeno del

guscio, la stella inizia a fondere l’elio, e in questo processo diventa instabile. Convulsioni profonde,

combinate con la pressione della radiazione e altre forze, scagliano nello spazio gli strati

superficiali, dando vita a una nebulosa planetaria.

Le nebulose planetarie non sono però così ariose e tranquille come suggeriscono le loro

immagini: al contrario, sono massicce e tempestose. Ciascuna di esse contiene l’equivalente di circa

un terzo della massa del Sole, compreso quasi tutto il combustibile nucleare inutilizzato. All’ inizio

gli strati superficiale della stella sono espulsi a una velocità compresa fra i 10 e 20 chilometri ala

secondo, un flusso relativamente lento, che trasporta la maggior parte della massa finale della

nebulosa. Man mano che la stella si spoglia fino a scoprire il nucleo ancora caldo, il suo colore

passa dall’arancione al giallo, poi al bianco e infine al blu. Quando la temperatura della superficie

supera i 25.000 Kelvin, la stella sommerge i gas circostanti di una intensa luce ultravioletta,

abbastanza potente da smembrare le molecole e strappare gli elettroni dagli atomi. Il vento stellare

trasporta una massa via via inferiore, ma a una velocità sempre più alta. Dopo un periodo di durata

variabile fra 100.000 anni e un milione, a seconda della massa originaria, il vento si placa del tutto,

e la stella diventa una “nana bianca” estremamente densa e calda: un tizzone ardente stellare che la

gravità ha compresso fino a farne una sfera delle dimensioni della Terra.

Poiché le forze che espellono la massa dalle stelle morenti hanno simmetria sferica, almeno

secondo la teoria più accreditata, fino agli anni ottanta gli astronomi hanno pensato che le nebulose

planetarie fossero bolle sferiche in espansione. Da allora, però, lo scenario si è fatto sempre più

complicato. E sempre più interessante.

Venti stellari

Il primo indizio che le nebulose planetarie fossero qualcosa di più che semplici rigurgiti

stellari risale al 1978, quando le osservazioni nell’ultravioletto mostrarono che il vento delle stelle

morenti continua a soffiare anche molto tempo dopo l’espulsione degli stati gassosi più esterni. I

gas sono molto rarefatti, ma questi venti raggiungono velocità di 1000 chilometri al secondo, cento

volte superiori a quelle dei venti più densi che li precedono.

Per spiegare gli effetti di questi venti, è stato preso in prestito un modello dei venti stellari

elaborato per spiegare altri fenomeni astrofisica. Secondo questa ipotesi, quando i venti rapidi si

scontrano con quelli più lenti espulsi in precedenza, nel punto di incontro si forma un denso bordo

di gas compressi. Questo anello tridimensionale di gas, più precisamente “toro”, circonda una cavità

quasi vuota (ma estremamente calda); con il tempo, il vento veloce svuota un volume di spazio

sempre più grande.

Questo modello, detto “ipotesi dei venti stellari interagenti”, funziona bene per le strutture

sferiche o quasi sferiche. Ma negli anni ottanta si cominciò a capire che le nebulose planetarie

sferiche sono un’eccezione: probabilmente sono solo il dieci percento del totale. Molte altre hanno

forme allungate, a uova, mentre le più spettacolari, anche se più rare, presentano due bolle sui lati

opposti della stella morente. Gli astronomi le chiamano “bipolari”, anche se sarebbe più corretto, e

più vivido, definirle “a farfalla” o “a clessidra”.

Per spiegare queste forme si è allargato il concetto dei venti interagenti. Supponiamo che i

venti meno veloci riescano a formare un denso anello che ruota attorno all’equatore della stella. In

un secondo momento, l’anello toro defletterà debolmente i venti stellari verso i poli, dando origine a

una nebulosa ellittica. Le nebulose a forma di clessidra, sono quelle con un anello molto leggero e

molto denso, che funziona come un ugello, un po’ come fanno le labbra quando fischiamo, facendo

convergere il fiato in un sottile getto d’aria. Analogamente, gli anelli che deflettono con forza i

venti veloci, produrranno una coppia speculare di getti, o flussi di gas, a forma di clessidra.

Il modello era semplice e spiegava bene tutte le immagini disponibili fino al 1993. Le

simulazioni al computer confermavano la validità dell’idea di base, mentre nuove osservazioni

testimoniavano che i venti meno rapidi sembravano realmente più densi vicino all’equatore.

Nel 1994 Hubble scattò la sua prima fotografia chiara di una nebulosa planetaria, la Occhio

di Gatto (ufficialmente classificata come NCG 6543): un’immagine fatale, sconvolgente. Una delle

due ellissi incrociate, un bordo sottile che circonda una cavità a forma di ellisse, corrispondeva al

modello, ma che cosa erano le altre strutture? Nessuno aveva previsto le indistinte regioni rossastre

che legavano la nebulosa, e i filamenti simili a getti erano ancora più strani. Nella migliore delle

ipotesi il modello è valido solo in parte.

Teorici in un mare di guai

Non è sempre facile rinunciare a un’ipotesi scientifica che sembrava funzionare, per cui

sperammo che l’Occhio di Gatto fosse un’anomalia. Non lo era. Presto arrivarono altre immagini di

Hubble che toglievano ogni dubbio: nella nostra ricostruzione della morte stellar mancavano alcuni

elementi fondamentali. A parte l’ego ferito, era una situazione ideale per dei ricercatori. Quando le

idee a cui siete affezionati sono finite in pezzi, la natura vi sta sfidando a ricominciare a osservare:

che cosa ti è sfuggito? A che cosa hai trascurato di prestare attenzione?

In situazioni simili, bisogna concentrarsi sui casi estremi, perché sono quelli in cui le forze

sconosciute operano con più evidenza. Tra le nebulose planetarie, i casi più estremi sono gli oggetti

bipolari. Le strutture più piccole che ornano le nebulose sono speculari, una su ciascun lato della

nebulosa. E questa simmetria significa che l’intera struttura è stata assemblata in modo coerente da

processi organizzati che operano in prossimità della superficie della stella, un po’ come accade

quando si forma un fiocco di neve.

Per questi oggetti il modello dei venti interagenti fa una previsione che è facile verificare:

una volta che il gas ha lasciato l’anello, viaggia verso l’esterno a velocità costante, producendo un

particolare spostamento Doppler della luce emessa dal gas. Ebbene, non è così. Nel 2000 il gruppo

di Romano Corradi, che ora lavora ai telescopi Isaac Newton, alle Canarie, ha studiato con Hubble

la nebulosa del Granchi Australe (He2-104), scoprendo che la velocità di espansione, cresce in

proporzione alla distanza dalla stella. I gas più lontani erano li semplicemente perché si muovevano

più velocemente. Risalendo indietro nel tempo, l’incantevole nebulosa a clessidra sembra essersi

formata circa 5700 anni fa in una singola eruzione. Il modello dei venti interagenti, che presume un

vento costante che modella la nebulosa, era insostenibile. Ancora più strana è stata un’altra scoperta

di Corradi e colleghi: la nebulosa del Granchi Australe è costituita in realtà da due nebulose, una

dentro l’altra come le bambole di una matrioska. Immaginammo che la nebulosa più interna fosse

semplicemente la più giovane delle due, ma le osservazioni hanno mostrato con chiarezza che

entrambe le nebulose avevano lo stesso andamento di velocità crescenti con la distanza. L’intera

complessa struttura doveva essersi formata in un evento molto scenografico, avvenuto sei millenni

fa. Ma su questa scoperta ci stiamo arrovellando ancora oggi.

Rimescolare le carte

I primi, promettenti abbozzi di teorie sulla formazione delle nebulose planetarie non

mancano: il difficile è sviluppare modelli che abbraccino tutte le osservazioni. Oggi si concorda sul

fatto che uno dei principali fattori in gioco è l’influsso gravitazionale di stelle compagne. Almeno la

metà delle “stelle” che si vedono di notte sono in realtà sistemi binari, in cui due oggetti orbitano

attorno a un comune centro di massa. Nella maggior parte di questi sistemi le stelle sono così

lontane da svilupparsi in modo indipendente ma in una piccola frazione di casi la gravità di una

stella può deflettere o persino catturare il materiale che fluisce dall’altra. Questa frazione

corrisponde al numero di nebulose planetarie bipolari.

Nel loro scenario, la compagna cattura il materiale che fluisce da una stella morente. In un

sistema in cui le orbite sono più piccole di quelle di Mercurio e un anno si misura in giorni terrestri,

questo trasferimento è macchinoso. Quando il materiale della stella morente raggiunge la

compagna, quest’ultima si è portate ben avanti nella sua orbita. Il materiale forma allora una coda

che segue la stella più densa e finisce per organizzarsi in un disco spesso e denso che le ruota

attorno. Le simulazioni indicano che anche una compagna con un’orbita ampia quanto quella di

Nettuno potrebbe raccogliere intorno a se un disco di accrescimento.

E possono presentarsi anche sviluppi imprevisti. La stella morente aumentando via via di

dimensioni, a volte può addirittura inghiottire la compagna e il disco, procurandosi l’equivalente

cosmico di un’indigestione. Compagna e disco iniziano quindi un’orbita a spirale dentro il corpo

della stella più grande, rimodellandola e appiattendola dall’interno, mentre i getti di materia diretti

verso l’esterno vengono incurvati. Gradualmente, la compagna sprofonda nella stella morente fino a

fondersi con il suo nucleo, interrompendo del tutto il flusso di materia verso l’esterno. Questo

processo potrebbe spiegare come mai alcune nebulose sembrano il risultato di un flusso

bruscamente interrotto.

Una guida magnetica

Le stelle compagne dei sistemi binari, non sono gli unici possibili “scultori” di nebulose

planetarie. Anche i campi magnetici della stella morente o del disco di accrescimento attorno alla

compagna potrebbero svolgere un ruolo importante. Poiché la maggior parte del gas è ionizzato, i

campi magnetici possono guidarne il moto. I più intensi agiscono come fasce di gomma rigida che

modellano il flusso del gas, più o meno come fa il campo magnetico terrestre quando sottrae

particelle dal vento solare, e le dirige nelle regioni polari, dove danno vita alle aurore. A loro volta i

venti stellari possono stirare, piegare o attorcigliare i campi.

Alla fine degli anni novanta, Roger A. Chevalier e Ding Luo dell’Università della Virginia

avanzarono l’ipotesi che i venti stellari trasportassero anelli di campo magnetico. Il braccio di ferro

tra campo magnetico e gas può sagomare il flusso di materia in forme esotiche. Purtroppo il

modello prevede che il campo iniziale sia molto debole, e non svolga alcun ruolo nella genesi del

vento. E questo è un problema, perché la presenza di campi magnetici attivi sulla superficie delle

stelle sembra indispensabile per lanciare i venti.

Un’altra strada è stata quella di indagare in che modo forti campi magnetici possono

scagliare materia nello spazio. Mentre la convezione agita una stella morente, i campi ancorati al

nucleo si sollevano con i gas che galleggiano verso la superficie e, se il nucleo ruota rapidamente,

vengono arrotolati come una molla. Quando raggiungono la superficie, i campi si spezzano e

sparano il materiale verso l’esterno. Un processo simile potrebbe avvenire in un disco di

accrescimento magnetizzato. In realtà stella e disco, possono alimentare un gruppo di venti

ciascuno, e il disallineamento dei loro assi potrebbe produrre alcune strane forme bipolari osservate

nelle nebulose planetarie giovani. Uno degli autori sta studiando questi effetti . Il punto è che i

campi magnetici, come le stelle binarie, producono forze aggiuntive in grado di produrre una

gamma di forme ben più ampia di quella del modello dei venti interagenti.

La nostra comprensione di come le stelle smembrate diano vita alle nebulose planetarie ha

fatto qualche progresso, anche se è ancora immatura, ma la descrizione generale della morte stellare

è un modello consolidato. Le stelle evolvono in modo che, quando si spengono, i loro “motori”

perdono colpi ed espellono gli strati più esterni nello spazio. Di fatto, la teoria della struttura e

dell’evoluzione stellare è una delle teorie scientifiche di maggior successo del XX secolo, che

spiega in modo eccellente le osservazioni di gran parte delle stelle: la loro emissione luminosa, i

loro colori e anche molte bizzarrie. Tuttavia non mancano alcune lacune, specialmente sull’inizio e

sulla fine della loro vita.

Crediamo di aver identificato gli strumenti con cui le stelle morenti modellano la materia

che scagliano nello spazio. Ciò che ancora non comprendiamo sono le leggi che determinano la

creazione di strutture armoniose come le nebulose planetarie. Che cosa alimenta i venti stellari?

Quanto sono importanti le stelle compagne? Quale ruolo svolgono i campi magnetici? Che cosa

crea le nebulose a più lobi?

Nelle pagine seguenti alcuni stupendi esempi di nebulose

planetarie!

Examples of Planetary Nebulae

The Unveiling of a Planetary Nebula

Credit: Matt Bobrowsky, Orbital Sciences Corporation and NASA

This HST Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 image captures the infancy of the Stingray

Nebula (Hen-1357), the youngest known planetary nebula.

In this image, the bright central star is in the middle of the green ring of gas. Its companion

star is diagonally above it at 10 o'clock. A spur of gas (green) is forming a faint bridge to the

companion star due to gravitational attraction.

The image also shows a ring of gas (green) surrounding the central star, with bubbles of gas to

the lower left and upper right of the ring. The wind of material propelled by radiation from the

hot central star has created enough pressure to blow open holes in the ends of the bubbles,

allowing gas to escape.

The red curved lines represent bright gas that is heated by a "shock" caused when the central

star's wind hits the walls of the bubbles.

The nebula is as large as 130 solar systems, but, at its distance of 18,000 light-years, it

appears only as big as a dime viewed a mile away. The Stingray is located in the direction of

the southern constellation Ara (the Altar).

The colors shown are actual colors emitted by nitrogen (red), oxygen (green), and hydrogen

(blue). The filters used were F658N ([N II]), F502N ([O III]), and F487N (H-beta). The

observations were made in March 1996.

NGC 6543

The Cat's Eye Nebula

Credits: J.P. Harrington and K.J. Borkowski (University of Maryland), and NASA

This NASA Hubble Space Telescope image shows one of the most complex planetary nebulae

ever seen, NGC 6543, nicknamed the "Cat's Eye Nebula." Hubble reveals surprisingly intricate

structures including concentric gas shells, jets of high-speed gas and unusual shock-induced

knots of gas. Estimated to be 1,000 years old, the nebula is a visual "fossil record" of the

dynamics and late evolution of a dying star.

A preliminary interpretation suggests that the star might be a double-star system. The

dynamical effects of two stars orbiting one another most easily explains the intricate

structures, which are much more complicated than features seen in most planetary nebulae.

(The two stars are too close together to be individually resolved by Hubble, and instead,

appear as a single point of light at the center of the nebula.)

According to this model, a fast "stellar wind" of gas blown off the central star created the

elongated shell of dense, glowing gas. This structure is embedded inside two larger lobes of

gas blown off the star at an earlier phase. These lobes are "pinched" by a ring of denser gas,

presumably ejected along the orbital plane of the binary companion.

The suspected companion star also might be responsible for a pair of high-speed jets of gas

that lie at right angles to this equatorial ring. If the companion were pulling in material from a

neighboring star, jets escaping along the companion's rotation axis could be produced.These

jets would explain several puzzling features along the periphery of the gas lobes. Like a stream

of water hitting a sand pile, the jets compress gas ahead of them, creating the "curlicue"

features and bright arcs near the outer edge of the lobes. The twin jets are now pointing in

different directions than these features. This suggests the jets are wobbling, or precessing, and

turning on and off episodically.This color picture, taken with the Wide Field Planetary Camera2, is a composite of three images taken at different wavelengths. (red, hydrogen-alpha; blue,

neutral oxygen, 6300 angstroms; green, ionized nitrogen, 6584 angstroms). The image was

taken on September 18, 1994. NGC 6543 is 3,000 light-years away in the northern

constellation Draco.The term planetary nebula is a misnomer; dying stars create these cocoons

when they lose outer layers of gas. The process has nothing to do with planet formation, which

is predicted to happen early in a star's life.This material was presented at the 185th meeting of

the American Astronomical Society in Tucson, AZ on January 11, 1995.

The Hourglass Nebula

Credit: Raghvendra Sahai and John Trauger (JPL), the WFPC2 science team, and NASA

This is an image of MyCn18, a young planetary nebula located about 8,000 light-years away,

taken with the Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) aboard NASA's Hubble Space

Telescope (HST). This Hubble image reveals the true shape of MyCn18 to be an hourglass with

an intricate pattern of "etchings" in its walls. This picture has been composed from three

separate images taken in the light of ionized nitrogen (represented by red), hydrogen (green),

and doubly-ionized oxygen (blue). The results are of great interest because they shed new

light on the poorly understood ejection of stellar matter which accompanies the slow death of

Sun-like stars. In previous ground-based images, MyCn18 appears to be a pair of large outer

rings with a smaller central one, but the fine details cannot be seen.

According to one theory for the formation of planetary nebulae, the hourglass shape is

produced by the expansion of a fast stellar wind within a slowly expanding cloud which is more

dense near its equator than near its poles. What appears as a bright elliptical ring in the

center, and at first sight might be mistaken for an equatorially dense region, is seen on closer

inspection to be a potato shaped structure with a symmetry axis dramatically different from

that of the larger hourglass. The hot star which has been thought to eject and illuminate the

nebula, and therefore expected to lie at its center of symmetry, is clearly off center. Hence

MyCn18, as revealed by Hubble, does not fulfill some crucial theoretical expectations.

Hubble has also revealed other features in MyCn18 which are completely new and unexpected.

For example, there is a pair of intersecting elliptical rings in the central region which appear to

be the rims of a smaller hourglass. There are the intricate patterns of the etchings on the

hourglass walls. The arc-like etchings could be the remnants of discrete shells ejected from the

star when it was younger (e.g. as seen in the Egg Nebula), flow instabilities, or could result

from the action of a narrow beam of matter impinging on the hourglass walls. An unseen

companion star and accompanying gravitational effects may well be necessary in order to

explain the structure of MyCn18.

The Spirograph Nebula

Image Credit: NASA and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA) Acknowledgement: Dr. Raghvendra Sahai (JPL) and Dr.

Arsen R. Hajian (USNO)

Glowing like a multi-faceted jewel, the planetary nebula IC 418 lies about 2,000 light-years

from Earth in the direction of the constellation Lepus. This photograph is one of the latest from

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, obtained with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2.

A planetary nebula represents the final stage in the evolution of a star similar to our Sun. The

star at the center of IC 418 was a red giant a few thousand years ago, but then ejected its

outer layers into space to form the nebula, which has now expanded to a diameter of about

0.1 light-year. The stellar remnant at the center is the hot core of the red giant, from which

ultraviolet radiation floods out into the surrounding gas, causing it to fluoresce. Over the next

several thousand years, the nebula will gradually disperse into space, and then the star will

cool and fade away for billions of years as a white dwarf. Our own Sun is expected to undergo

a similar fate, but fortunately this will not occur until some 5 billion years from now.

The Hubble image of IC 418 is shown in a false-color representation, based on Wide Field

Planetary Camera 2 exposures taken in February and September, 1999 through filters that

isolate light from various chemical elements. Red shows emission from ionized nitrogen (the

coolest gas in the nebula, located furthest from the hot nucleus), green shows emission from

hydrogen, and blue traces the emission from ionized oxygen (the hottest gas, closest to the

central star). The remarkable textures seen in the nebula are newly revealed by the Hubble

telescope, and their origin is still uncertain.

Looking Down a Barrel of Gas at a Doomed Star

M57, The Ring Nebula

Credit: Hubble Heritage Team (AURA/STScI/NASA)

The NASA Hubble Space Telescope has captured the sharpest view yet of the most famous of

all planetary nebulae: the Ring Nebula (M57). In this October 1998 image, the telescope has

looked down a barrel of gas cast off by a dying star thousands of years ago. This photo reveals

elongated dark clumps of material embedded in the gas at the edge of the nebula; the dying

central star floating in a blue haze of hot gas. The nebula is about a light-year in diameter and

is located some 2,000 light-years from Earth in the direction of the constellation Lyra.

The colors are approximately true colors. The color image was assembled from three blackand-white photos taken through different color filters with the Hubble telescope's Wide Field

Planetary Camera 2. Blue isolates emission from very hot helium, which is located primarily

close to the hot central star. Green represents ionized oxygen, which is located farther from

the star. Red shows ionized nitrogen, which is radiated from the coolest gas, located farthest

from the star. The gradations of color illustrate how the gas glows because it is bathed in

ultraviolet radiation from the remnant central star, whose surface temperature is a white-hot

216,000 degrees Fahrenheit (120,000 degrees Celsius).

NGC 3132

The Glowing Pool Nebula

Credit: Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA/NASA)

NGC 3132 is a striking example of a planetary nebula. This expanding cloud of gas,

surrounding a dying star, is known to amateur astronomers in the southern hemisphere as the

"Eight-Burst" or the "Southern Ring" Nebula.

The name "planetary nebula" refers only to the round shape that many of these objects show

when examined through a small visual telescope. In reality, these nebulae have little or

nothing to do with planets, but are instead huge shells of gas ejected by stars as they near the

ends of their lifetimes. NGC 3132 is nearly half a light year in diameter, and at a distance of

about 2000 light years is one of the nearer known planetary nebulae. The gases are expanding

away from the central star at a speed of 9 miles per second.

This image, captured by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope, clearly shows two stars near the

center of the nebula, a bright white one, and an adjacent, fainter companion to its upper right.

(A third, unrelated star lies near the edge of the nebula.) The faint partner is actually the star

that has ejected the nebula. This star is now smaller than our own Sun, but extremely hot. The

flood of ultraviolet radiation from its surface makes the surrounding gases glow through

fluorescence. The brighter star is in an earlier stage of stellar evolution, but in the future it will

probably eject its own planetary nebula.

In the Heritage Team's rendition of the Hubble image, the colors were chosen to represent the

temperature of the gases. Blue represents the hottest gas, which is confined to the inner

region of the nebula. Red represents the coolest gas, at the outer edge. The Hubble image also

reveals a host of filaments, including one long one that resembles a waistband, made out of

dust particles which have condensed out of the expanding gases. The dust particles are rich in

elements such as carbon. Eons from now, these particles may be incorporated into new stars

and planets when they form from interstellar gas and dust. Our own Sun may eject a similar

planetary nebula some 6 billion years from now.

NGC 2440

Credit: NASA/The Hubble Heritage Team (AURA/STScI).

The central star of NGC 2440 is one of the hottest known, with a surface temperature near

200,000 degrees Celsius. The complex structure of the surrounding nebula suggests to some

astronomers that there have been periodic oppositely directed outflows from the central star,

somewhat similar to that in NGC 2346, but in the case of NGC 2440 these outflows have been

episodic, and in different directions during each episode. The nebula is also rich in clouds of

dust, some of which form long, dark streaks pointing away from the central star. In addition to

the bright nebula, which glows because of fluorescence due to ultraviolet radiation from the

hot star, NGC 2440 is surrounded by a much larger cloud of cooler gas which is invisible in

ordinary light but can be detected with infrared telescopes. NGC 2440 lies about 4,000 lightyears from Earth in the direction of the constellation Puppis.

The Hubble Heritage team made this image from observations of NGC 2440 acquired by

Howard Bond (STScI) and Robin Ciardullo (Penn State).

The Glowing Eye of NGC 6751

Credit: NASA, The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

Astronomers using NASA's Hubble Space Telescope have obtained images of the strikingly

unusual planetary nebula, NGC 6751. Glowing in the constellation Aquila like a giant eye, the

nebula is a cloud of gas ejected several thousand years ago from the hot star visible in its

center.

"Planetary nebulae" are named after their round shapes as seen visually in small telescopes,

and have nothing else to do with planets. They are shells of gas thrown off by stars of masses

similar to that of our own Sun, when the stars are nearing the ends of their lives. The loss of

the outer layers of the star into space exposes the hot stellar core, whose strong ultraviolet

radiation then causes the ejected gas to fluoresce as the planetary nebula. Our own Sun is

predicted to eject its planetary nebula some 6 billion years from now.

The Hubble observations were obtained in 1998 with the Wide Field Planetary Camera 2

(WFPC2) by a team of astronomers led by Arsen Hajian of the U.S. Naval Observatory in

Washington, DC. The Hubble Heritage team, working at the Space Telescope Science Institute

in Baltimore, has prepared this color rendition by combining the Hajian team's WFPC2 images

taken through three different color filters that isolate nebular gases of different temperatures.

The nebula shows several remarkable and poorly understood features. Blue regions mark the

hottest glowing gas, which forms a roughly circular ring around the central stellar remnant.

Orange and red show the locations of cooler gas. The cool gas tends to lie in long streamers

pointing away from the central star, and in a surrounding, tattered-looking ring at the outer

edge of the nebula. The origin of these cooler clouds within the nebula is still uncertain, but

the streamers are clear evidence that their shapes are affected by radiation and stellar winds

from the hot star at the center. The star's surface temperature is estimated at a scorching

140,000 degrees Celsius (250,000 degrees Fahrenheit).

Hajian and his team are scheduled to reobserve NGC 6751 with Hubble's WFPC2 in 2001. Due

to the expansion of the nebula, at a speed of about 40 kilometers per second (25 miles per

second), the high resolution of Hubble's camera will reveal the slight increase in the size of the

nebula since 1998. This measurement will allow the astronomers to calculate an accurate

distance to NGC 6751. In the meantime, current estimates are that NGC 6751 is roughly 6,500

light-years from Earth. The nebula's diameter is 0.8 light-years, some 600 times the diameter

of our own solar system.

Beauty in the Eye of Hubble

Image Credit: NASA and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

Acknowledgment: C.R. O'Dell (Vanderbilt University)

Like many other so-called planetary nebulae, IC 4406 exhibits a high degree of symmetry; the

left and right halves of the Hubble image are nearly mirror images of the other. If we could fly

around IC4406 in a starship, we would see that the gas and dust form a vast donut of material

streaming outward from the dying star. From Earth, we are viewing the donut from the side.

This side view allows us to see the intricate tendrils of dust that have been compared to the

eye's retina. In other planetary nebulae, like the Ring Nebula (NGC 6720), we view the donut

from the top.

The donut of material confines the intense radiation coming from the remnant of the dying

star. Gas on the inside of the donut is ionized by light from the central star and glows. Light

from oxygen atoms is rendered blue in this image; hydrogen is shown as green, and nitrogen

as red. The range of color in the final image shows the differences in concentration of these

three gases in the nebula.

Unseen in the Hubble image is a larger zone of neutral gas that is not emitting visible light, but

which can be seen by radio telescopes.

One of the most interesting features of IC 4406 is the irregular lattice of dark lanes that crisscross the center of the nebula. These lanes are about 160 astronomical units wide (1

astronomical unit is the distance between the Earth and Sun). They are located right at the

boundary between the hot glowing gas that produces the visual light imaged here and the

neutral gas seen with radio telescopes. We see the lanes in silhouette because they have a

density of dust and gas that is a thousand times higher than the rest of the nebula. The dust

lanes are like a rather open mesh veil that has been wrapped around the bright donut.

The fate of these dense knots of material is unknown. Will they survive the nebula's expansion

and become dark denizens of the space between the stars or simply dissipate?

This image is a composite of data taken by Hubble's Wide Field Planetary Camera 2 in June

2001 by Bob O'Dell (Vanderbilt University) and collaborators and in January 2002 by The

Hubble Heritage Team (STScI). Filters used to create this color image show oxygen, hydrogen,

and nitrogen gas glowing in this object.

Ant-like Space Structure Previews Death of Our Sun

Credit: NASA, ESA and The Hubble Heritage Team (STScI/AURA)

Acknowledgment: R. Sahai (JPL) and B. Balick (University of Washington)

From ground-based telescopes, the so-called "ant nebula" (Menzel 3, or Mz3) resembles the

head and thorax of a garden-variety ant. This dramatic NASA/ESA Hubble Space Telescope

image, showing 10 times more detail, reveals the "ant's" body as a pair of fiery lobes

protruding from a dying, Sun-like star. The Hubble images directly challenge old ideas about

the last stages in the lives of stars. By observing Sun-like stars as they approach their deaths,

the Hubble Heritage image of Mz3 -- along with pictures of other planetary nebulae -- shows

that our Sun's fate probably will be more interesting, complex, and striking than astronomers

imagined just a few years ago. Though approaching the violence of an explosion, the ejection

of gas from the dying star at the center of Mz3 has intriguing symmetrical patterns unlike the

chaotic patterns expected from an ordinary explosion. Scientists using Hubble would like to

understand how a spherical star can produce such prominent, non-spherical symmetries in the

gas that it ejects. One possibility is that the central star of Mz3 has a closely orbiting

companion that exerts strong gravitational tidal forces, which shape the outflowing gas. For

this to work, the orbiting companion star would have to be close to the dying star, about the

distance of the Earth from the Sun. At that distance the orbiting companion star wouldn't be

far outside the hugely bloated hulk of the dying star. It's even possible that the dying star has

consumed its companion, which now orbits inside of it, much like the duck in the wolf's belly in

the story "Peter and the Wolf." A second possibility is that, as the dying star spins, its strong

magnetic fields are wound up into complex shapes like spaghetti in an eggbeater. Charged

winds moving at speeds up to 1000 kilometers per second from the star, much like those in

our Sun's solar wind but millions of times denser, are able to follow the twisted field lines on

their way out into space. These dense winds can be rendered visible by ultraviolet light from

the hot central star or from highly supersonic collisions with the ambient gas that excites the

material into florescence. No other planetary nebula observed by Hubble resembles Mz3 very

closely. M2-9 comes close, but the outflow speeds in Mz3 are up to 10 times larger than those

of M2-9. Interestingly, the very massive, young star, Eta Carinae, shows a very similar outflow

pattern.