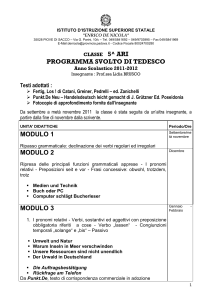

SCUOLA SUPERIORE PER MEDIATORI LINGUISTICI

(Decreto Ministero dell’Università 31/07/2003)

Via P. S. Mancini, 2 – 00196 – Roma

TESI DI DIPLOMA

DI

MEDIATORE LINGUISTICO

(Curriculum Interprete e Traduttore)

Equipollente ai Diplomi di Laurea rilasciati dalle Università al termine dei Corsi afferenti alla

classe delle

LAUREE UNIVERSITARIE

IN

SCIENZE DELLA MEDIAZIONE LINGUISTICA

La traduzione musicale

RELATORI:

prof.ssa Adriana Bisirri

CORRELATORI:

prof. Alfredo Rocca

prof. Wolfram Kraus

prof.ssa Claudia Piemonte

CANDIDATA:

Mariella Rondini

ANNO ACCADEMICO 2014/2015

~2~

Sommario

INTRODUZIONE 5

1.

STORIA DELLA TRADUZIONE MUSICALE

7

2.

STUDI SULLA TRADUZIONE MUSICALE

9

3.

ANALISI SOCIO-SEMIOTICA 18

3.1 CANZONI A CONFRONTO: ANALISI SOCIO-SEMIOTICA E MUSICALE 20

4.

APPROCCIO PRATICO ALLA TRADUZIONE MUSICALE

4.1

PRIMO APPROCCIO ALLA TRADUZIONE

4.2

LA TEORIA DELLO SKOPOS

30

4.3

OSSERVAZIONI 33

4.4

IL PRINCIPIO PENTATHLON

40

4.4.1 Cantabilità 41

4.3.2 Senso 43

4.3.3 Naturalezza 44

4.3.4 Ritmo 46

4.3.5 Rime 49

CONCLUSIONI

27

28

50

ENGLISH SECTION

53

INTRODUCTION 55

1. STUDIES ON SONG TRANSLATION 56

2. SOCIO-SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS 61

2.1

COMPARISON BETWEEN SONGS: SOCIO-SEMIOTIC AND MUSICAL ANALYSIS.

3. A PRACTICAL APPROACH TO SONG TRANSLATION

70

3.1

First approach to music- linked translation

71

3.2

The Skopos Theory 73

3.3

The Pentathlon Principle

76

CONCLUSION

85

EINLEITUNG

89

1.

2.

STUDIEN ÜBER DIE MUSIKALISCHE ÜBERSETZUNG

SOZIO-SEMIOTISCHE ANALYSE

97

3.1

Erste Annäherung an die Musik-Übersetzung

3.2

Die Skopostheorie 102

3.2

Pentathlon- Prinzip 105

RINGRAZIAMENTI

BIBLIOGRAFIA

110

113

~3~

91

100

63

~4~

Introduzione

Nonostante la musica sia una parte integrante e fondamentale delle

nostre vite, la traduzione musicale è ancora oggi un campo trascurato

dagli studiosi. Dopotutto, la musica non è più solo uno svago, ma anche

un importante mezzo di comunicazione di massa e un prodotto in grado

di rispecchiare non solo gli usi e i costumi di una determinata cultura, ma

anche i desideri di una società. Come parte delle nostre vite, inoltre ci

segue ovunque andiamo: mezzi di trasporto, bar, locali, ristoranti,

negozi. Riusciamo a seguirla anche sotto forma visiva, attraverso la

televisione o andando a concerti.

Quello della traduzione musicale è uno strano fenomeno, perché

quasi non se ne parla, nonostante la grande quantità di cover presenti in

ogni cultura. Anche le canzoni dei musical subiscono un processo di

traduzione e riadattamento prima di essere mandate in onda in un altro

paese.

Allora perché è cosi difficile trovare qualche studioso della

traduzione che se ne occupi? La risposta, in realtà, non è poi così

difficile: la traduzione musicale non è una traduzione vera e propria.

~5~

Comprende una gamma molto più ampia di fattori da tenere in

considerazione. Non si tratta solamente di fattori legati al ritmo, al

tempo, all‟intonazione, alle forzature all‟interno di un testo o dello

schema metrico; si tratta di fattori sociali e culturali, soprattutto se la

canzone che andremo a tradurre è una canzone popolare.

Qui vorrei fare una piccola digressione sui termini “pop” e

“popolare”.

Quando si pensa alla musica popolare, non si deve

commettere l‟errore di pensare alla musica etnica o folkloristica, bensì

all‟accezione

inglese

dell‟espressione

“popular

music”,

che

contraddistingue tutti quei generi e le correnti nati all‟interno dell‟epoca

dell‟industria musicale. Si parla di tutta quella musica, che spazia

dall‟underground al mainstream, rivolta a un pubblico di massa

eterogeneo. La musica “pop”, quindi è un sottogenere della musica

popolare, proprio come il rock. Per il resto della mia tesi continuerò,

quindi, a riferirmi alla musica popolare rivolta a un pubblico di massa,

perché prodotta da etichette musicali.

~6~

1. Storia della traduzione musicale

La traduzione musicale era un fenomeno molto in voga negli anni

‟60 e ‟70, soprattutto in Italia. Agli inizi degli anni ‟60 iniziavano ad

apparire i primi gruppi rock, come i Beatles e i Kinks, e soprattutto iniziò

a diffondersi la musica beat. Questa musica proveniva quasi tutta dalla

vicina Inghilterra o dagli Stati Uniti, ma in Italia l‟inglese era capito da

pochissime persone, anche se era uno dei paesi in cui venivano venduti

più 45 giri. Erano proprio gli stessi discografici che premevano gli artisti

a esportare la propria musica in Italia e a cantarla in italiano. Molti artisti

italiani iniziarono quindi a tradurre canzoni straniere, anche se spesso,

per avere maggiore presa sul pubblico, i testi venivano stravolti e

completamente riscritti per i gusti degli abitanti del bel paese. Ci sono

molti esempi celebri, come Scende la pioggia1 di Gianni Morandi, cover

dell‟altrettanto famosa Elenore2 dei Turtles. Anche Adriano Celentano

ha completamente stravolto un grande della musica, Ben E. King,

traducendo la celeberrima Stand by me3, con Pregherò4. Anche se la

cover che ha segnato un‟intera generazione è stata Sognando California 5

1

Scende la pioggia/Il cigno bianco (1968) – RCA Italiana, PM 3476

The Turtles present the battle of the bands (1968) – White Whale Records

3

Stand by me (1961) – Atco Records

4

Pregherò (prima parte)/ Pasticcio in Paradiso (1962) – Clan, ACC 24005

5

Sognando la California/ Dolce di giorno (1966) – Dischi Records, SRL 10425

2

~7~

rifatta dai Dik Dik. Questa canzone è la traduzione di uno dei brani anni

‟60 più famosi al mondo: California Dreamin6 dei The Mamas and The

Papas.

Questo fenomeno, però, non si è arrestato dopo gli anni ‟70,

infatti, ancora oggi possiamo trovare delle traduzioni, più o meno fedeli,

di canzoni internazionali. Alcuni dei più famosi artisti italiani hanno

tradotto e riadattato brani stranieri, come ad esempio Luciano Ligabue (A

che ora è la fine del mondo 7, cover di It’s the end of the world as we

know it8, dei R.E.M.) o Vasco Rossi (Ad ogni costo9, cover di Creep10,

dei Radiohead).

Altri artisti, invece, hanno deciso di portare il loro successo

all‟estero (spesso nei paesi sudamericani o spagnoli), facendo uscire

versioni tradotte dei loro singoli o dei loro album, come nel caso di

Tiziano Ferro (che ha fatto uscire una versione spagnola di ogni suo

album in studio) e Laura Pausini. Anche se questa tendenza è stata

anticipata di molti anni già da Raffaella Carrà, che fece uscire molti

album in Spagna durante tutta la sua carriera.

6

If you can believe your eyes and ears (1965) – Dunhill Records

A che ora è la fine del mondo? (1994) – WEA Italiana

8

Document (1987) – I.R.S. Records

9

Tracks 2 – Inediti & Rarità (2009) - EMI

10

Pablo Honey (1993) - Parlophone

7

~8~

2. Studi sulla traduzione musicale

Come già affermato in precedenza, lo studio della traduzione di

brani musicali è sempre stato un campo molto trascurato dagli studiosi

ed i motivi sono molteplici. All‟inizio era molto difficile studiare questo

fenomeno, perché negli anni ‟50 e „60 spesso le canzoni uscivano quasi

tutte simultaneamente e non era facile capire chi fosse il vero autore di

un determinato brano o quale fosse la versione originale. Emblematico è

il caso della canzone The House of the Rising Sun, la cui versione più

famosa è quella degli Animals, nonostante l‟origine ancora oggi rimanga

sconosciuta. Oltre a questi problemi tecnici, ci sono anche problemi

linguistici e sociali. Quali sono i cambiamenti che rendono una canzone

una vera e propria hit? Quali aspetti bisogna migliorare per far avere

successo ad una canzone anche in un altro paese? Ma soprattutto, come

spiegare questi cambiamenti sia della parte musicale che della parte

testuale? Oltretutto, c‟è sempre chi non se ne occupa perché pensa che la

musica popolare sia banale. Ma se ci si fossilizza solamente sulla

cosiddetta “musica alta”, tutto ciò che ci si troverà ad affrontare saranno

solamente problemi linguistici su come tradurre giochi di parole e

metafore. Analizzare e studiare a fondo la musica popolare, non è

~9~

interessante solamente dal punto di vista linguistico, o musicale, ma

anche da un punto di vista sociologico, perché per rispondere alle

domande che ci siamo posti in precedenza, dobbiamo cercare di avere un

approccio interdisciplinare, in cui la linguistica, la sociologia e la

semiotica giocano insieme un ruolo fondamentale.

Quando parliamo di traduzione di canzoni popolari, dobbiamo

sempre tenere a mente il concetto di “traduzione bricolage”, introdotto

da Dick Hebdige nel suo libro Subculture11. Questo termine va ad

indicare le molteplici sfaccettature che la figura del traduttore deve

prendere in considerazione quando decide di affrontare la traduzione di

una canzone; il source text non è più l‟unica fonte a cui si deve attingere,

bensì bisogna conoscere e saper sfruttare la musica, lo stile vocale del

cantante, gli strumenti musicali, oltre ai valori culturali, le ideologie, ecc.

Il traduttore dovrà farsi carico di tutti questi aspetti, tutti egualmente

importanti, per poi far sì che il risultato sia un nuovo sistema unico e di

successo.

Una delle prime a parlare della traduzione della musica popolare è

stata la Haupt nella sua tesi di dottorato sugli aspetti linguistici e stilistici

della canzone popolare in Germania. Nella sua tesi, la Haupt afferma che

ci sono due tipi di traduzione: la prima che tende a cambiare

11

Hebdige, Dick, Subculture: the meaning of style, London, Routledge, 1979

~ 10 ~

completamente il testo originale; la seconda, invece, che cerca di essere

il più fedele possibile all‟originale, apportando cambiamenti solo dove la

musica lo impone ed è strettamente necessario. Questa sua tesi, però, non

viene approfondita e lascia l‟impressione che questo genere di

cambiamenti sia completamente arbitrario, mentre non è affatto cosi,

perché tutti i cambiamenti apportati ad un testo devono essere ben

studiati e ponderati.

Chi prova ad approfondire la distinzione in categorie è Hans

Christopher Worbs, nel suo studio sullo Schlager tedesco12. Analizzando

la grande discordanza tra testo e messaggio musicale delle canzoni che

vengono tradotte, Worbs conclude che ci sono due possibili motivi per

cui tutto ciò avviene: il primo riguarda il cantante; il pubblico si aspetta

un certo tipo di performance da un cantante che già conosce, insomma, si

aspetta che sia coerente con il suo stile. Quindi si può affermare che la

traduzione di una canzone dipenda dal background del cantante che

sceglie di farla propria. Il secondo motivo, invece, riguarda la mentalità

specifica di un paese, il che vale a dire che la traduzione di una canzone

dipende anche dal background socio culturale del paese. Queste ipotesi

12

Lo schlager (letteralmente battito o colpo, usato anche per intendere una canzonetta di successo) è

un genere di musica popolare diffuso prevalentemente nell'Europa Centrale e Settentrionale, in

particolar modo in Austria e in Germania.

~ 11 ~

sono molto valide, anche se ad oggi non sono state pienamente

supportate.

Un altro studio è stato effettuato dalla Stolting, ma il suo studio è

molto simile a quello della Haupt, tranne per il fatto che non prende il

considerazione le canzoni in cui avvengono i maggiori cambiamenti e

inoltre si ferma solo ad analizzare il linguaggio, non prendendo

minimamente

in

considerazione

gli

aspetti

non

verbali

della

performance.

Ci sono pochi esempi di studi che prendono in considerazione

anche l‟aspetto non verbale. Uno è quello di Pamies Betràn, che vede la

traduzione di canzoni come un transfer culturale e analizza delle

strategie per tradurre degli elementi linguistici specifici di una cultura.

Un altro è lo studio di Steinacher, che considera la parte verbale di una

canzone “flessibile”, rendendola solamente un mezzo per comunicare

uno specifico messaggio artistico che può essere analizzato solamente

insieme alla sua controparte non verbale.

La cosa che manca in tutte queste ricerche, però, è uno studio

socio-semiotico; viene dato per scontato che i significati delle canzoni e

delle rispettive traduzioni siano di interesse puramente linguistico,

mentre per capire a pieno i cambiamenti che portano alla stesura finale di

una canzone bisogna allargare l‟attenzione e studiare anche il contesto

~ 12 ~

sociale e culturale in cui una determinata canzone, piuttosto che un‟altra,

ha successo.

Com‟è possibile affrontare una traduzione tenendo conto della

semiotica e della cultura di arrivo? Un approccio socio- semiotico è stato

sviluppato da Itamar Even-Zohar, Gideon Toury e Theo Hermans. L‟idea

di base di questo studio è quella di vedere la traduzione come una serie

di testi interdipendenti, racchiusi all‟interno di vari sottosistemi che

vanno a formare un polisistema più complesso. Sembra difficile? In

realtà non lo è affatto. Ciò che succede, in pratica, è che secondo questo

sistema le traduzioni presentano determinate caratteristiche che sono il

risultato delle interrelazioni che corrono con gli altri testi che si trovano

nello stesso sistema. Quindi, le traduzioni, sia che se ne osservi la

funzione o il prodotto, possono essere studiate solamente in maniera

relazionale. Le caratteristiche individuali e distintive di una traduzione in

un determinato periodo o genere possono essere determinate solamente

nel contesto di queste relazioni. È solamente grazie al contesto della

società in cui si trova che un‟opera ottiene il suo valore.

Il sistema di Even-Zohar è un sistema binario, perché si basa tutto

su un centro e su un periferia. Nel centro, possiamo trovare disposte in

maniera ordinata tutte le opere più prestigiose, con i rispettivi generi

~ 13 ~

letterari. Nella periferia, invece, ci sono tutti i tipi di letteratura più

bassa, organizzati in maniera meno precisa.

Questa divisione tra centro e periferia, porta ad altre due

suddivisioni naturali, che determinano le dinamiche dello stesso sistema,

tra prodotti ritenuti più illustri ed altri ritenuti meno importanti. Anche se

l‟importanza di una determinata opera o di un certo genere non è certo

un fattore oggettivo, anzi, si tratta di una qualità attribuita dalle

istituzioni, dai gruppi di studiosi, dagli esperti, insomma, dalle persone;

quindi, questa opposizione deve essere osservata dal punto di vista

sociale. Ma cosa rende importante un‟opera? La sua funzione. E qui

nasce un‟altra suddivisione all‟interno di questo sistema : l‟opera ha una

funzione primaria o secondaria? Cioè, ha una funzione innovativa o

conservatrice all‟interno del sistema in cui si trova?

Questo studio è stato possibile perché nella nostra società la

letteratura è considerata come un artefatto che costituisce un sistema con

un‟evoluzione sistematica. Se analizzassimo anche la musica con gli

stessi parametri , potremmo notare come la musica popolare si trovi

proprio nella periferia di questo sistema, perché considerata da tutti non

importante e con una funzione sicuramente non innovativa perché

destinata ad accontentare le richieste di un pubblico di massa.

~ 14 ~

La teoria di Even-Zohar, arrivata a questo punto non è più capace

di fornirci risposte, anche se ci ha fornito una specie di struttura su cui

basare i nostri ragionamenti. Qui, entra in gioco l‟innovativa concezione

di Lambert sulla stesura di mappe che rappresentano gli utilizzi delle

diverse lingue in una determinata società. Il suo studio sulla traduzione

dei mass media si basa soprattutto sulla traduzione degli audiovisivi, ma

è applicabile anche al mondo della musica. Se tracciassimo una mappa ,

noteremmo che la produzione e la distribuzione della musica popolare è

in mano ad una concentrazione di poche major che riescono a

raggiungere il pubblico di tutto il mondo. La cartografia ci aiuta a

tracciare degli schemi che ci fanno capire che ciò che viene distribuito e

importato non è più una semplice canzone, ma un pacchetto contenente

anche un certo tipo di cultura, di linguaggio e di valori. Se studiato

attraverso la sociologia e la relazione tra paesi, ci si accorgerà che la

nazione che importa più di quanto esporta sarà in una posizione di

svantaggio rispetto a quella le cui esportazioni sono maggiori. Oltre ad

essere un problema di traduzione, quindi, diventa anche una problema

politico ed ideologico, perché un paese abituato ad una maggiore

influenza straniera sarà più semplice da accontentare, perché assuefatto

in qualche modo alla cultura che gli viene esportata. Mentre un paese

abituato ad ascoltare sempre la propria musica, farà più fatica a capire

~ 15 ~

quella degli altri; dovrà quindi essere svolto un lavoro maggiore per

fargliela comprendere.

Ciò che Lambert non prende in considerazione, però, è che la

musica è un oggetto che passa attraverso dei processi di mediazione, che

devono essere presi in considerazione quando si traduce. Negus ed

Hennion riconoscono tre differenti tipi di mediazione:

A.

AZIONE INTERMEDIARIA: riguarda i processi e le

interazioni che avvengono tra la produzione e il consumo della

musica popolare da parte del pubblico. Comprende tutti gli

interventi degli addetti al settore. I vari interventi non possono

essere concepiti come neutrali, ma hanno una funzione di

controllo.

B.

TRASMISSIONE: riguarda l‟impatto della tecnologia

sulla produzione, la distribuzione e il consumo della musica.

Soprattutto come gli strumenti ed i video musicali influenzano la

creazione e la ricezione del testo scritto.

C.

RELAZIONI SOCIALI: riguarda soprattutto le

ideologie e di come potrebbero privilegiare alcuni interessi a

discapito di altri.

~ 16 ~

Tutto ciò non deve far pensare che solo questo sia l‟aspetto che

conta, ovviamente anche l‟aspetto linguistico del testo è importante. Non

significa che la mediazione sia l‟unico processo che serve per scrivere e

tradurre un brano, ma è parte integrante del processo che quel brano

percorrerà prima di arrivare alla sua naturale destinazione. I vari testi

delle canzoni popolari sono inevitabilmente legati tra loro attraverso

tutto ciò che caratterizza il mondo della musica. I vari stili associati ai

generi musicali, i videoclip, le copertine dei CD, i diversi media che

trasmettono la musica, queste sono tutte cose che influenzano sia i

consumatori che gli artisti e sono parte integrante delle scelte che

vengono compiute ogni giorno in relazione a che album comprare o al

tipo di brano che si intende scrivere.

~ 17 ~

3. Analisi socio-semiotica

Ancora rimane da affrontare un ultimo problema. Quale ruolo

svolge la musica nel processo di traduzione socio-culturale? Sappiamo

bene che la musica ha un potere evocativo e associativo per chi la

ascolta. Ma questo potere sarà lo stesso anche in due lingue diverse?

Il problema con la musica popolare moderna è che viene ormai

percepita come mancante di originalità, vuota. Il suo unico scopo è

quello di piacere ad un pubblico sempre più ampio solo per essere

venduta. Va a risvegliare in chi la ascolta delle emozioni già esistenti e

piuttosto comuni; non lascia spazio all‟individualità dell‟artista o del

fruitore, perché il suo unico scopo è quello di essere apprezzata dalla

maggioranza. Proprio questa sua mancanza di originalità, però, la rende

cosi profondamente legata alla società, perché il testo perde di

importanza, il messaggio che l‟artista cerca di trasmettere perde di valore

e ciò che conta è che sia adatta al target a cui è indirizzata. Viene, quindi,

costruita ad hoc. Lo stesso termine popolare indica la sua stretta

relazione con il pubblico. La musica commerciale è talmente legata alla

società, che addirittura ne determina gli stessi valori. Come già detto in

precedenza, i cambiamenti che vengono apportati ad un testo durante il

~ 18 ~

processo di traduzione non possono essere arbitrari, e non possono

esserlo proprio perché sono dettati dai valori socio-culturali che

determinano anche lo stesso transfer culturale.

La musica popolare,

essendo cresciuta inseparabilmente con l‟industrializzazione della

società e della tecnologia, è prodotta con il solo scopo di essere venduta

alle masse e non può quindi essere analizzata secondo parametri che

riguardano solamente il suo aspetto musicale. Quest‟ultimo è secondario

e se si continua a prendere solamente quest‟aspetto in considerazione,

l‟ambito della traduzione musicale non fiorirà mai, perché mancano le

basi per creare dei mezzi analitici appropriati.

Chi riesce ad includere anche l‟aspetto semiotico, è lo studioso

Philip Tagg, che oltre a prendere in considerazione i soliti fattori quali

ritmo e schema metrico, amplia la ricerca anche ad altri aspetti, come il

timbro, la strumentazione, la tonalità, l‟armonia, l‟accentuazione, la

relazione tra voce e strumenti e gli aspetti dinamici, acustici e meccanici

di una canzone.

Utilizzando le linee guida da lui gettate possiamo

passare ad analizzare un source text ed un target text e cercare di capire

perché uno ha avuto più successo dell‟altro, a seconda del percorso di

integrazione culturale che ha effettuato.

~ 19 ~

3.1 Canzoni a confronto: analisi sociosemiotica e musicale

La traduzione che mi andrò ad analizzare è quella di una delle

canzoni più famose al mondo: My way13, di Frank Sinatra. Si tratta di

uno dei brani con più cover al mondo, ma molti non sanno che la

versione di Sinatra, quella più celebre, è essa stessa una cover di una

canzone francese intitolata Comme d’habitude14, cantata da Claude

François. La versione definitiva è stata composta da Jacques Revaux e

Claude François, che ha anche scritto il testo insieme a Gilles Thibaut.

All‟inizio la canzone era stata scritta in inglese e si intitolava For me, ma

venne rifiutata dagli artisti a cui era stata proposta perché ritenuta poco

originale. Così Revaux decise di proporla a François, che ne cambiò in

parte il testo e vi inserì il tema della coppia in crisi, basandosi sulla sua

esperienza personale con la cantante francese France Gall. La canzone

venne registrata e pubblicata nel 1967 e fu un grande successo in

Francia, entrando immediatamente nell‟hit parade. Prima che Paul Anka

decidesse di tradurla in inglese e di farla diventare il successo che tutti

noi oggi conosciamo, Claude François ne incise anche una versione in

13

14

My way (1969) – Reprise Records

Comme d’habitude (1967) – Disques Flèches, Philips

~ 20 ~

italiano, come si usava fare a quel tempo, ma questa versione non ebbe

mai successo e uscì infatti come lato B del 45 giri Se torni tu. Lo stesso

anno, il cantante e compositore Paul Anka si trovava in Francia, dove

ascoltò la canzone alla radio. Come lui stesso ammise molti anni dopo, la

canzone non gli piaceva molto, ma aveva quel quid in più che lo

convinse a dirigersi a Parigi per comprare i diritti per l‟adattamento del

brano in inglese. Una volta tornato in America, Anka rivoltò

completamente il testo della canzone, cucendolo perfettamente attorno

alla figura del suo amico Frank Sinatra. Non si trattava più di una

canzone che racconta un amore finito, ma la storia di un uomo che non

ha rimpianti per la sua vita, perché ha sempre vissuto a modo suo.

Esistono più di 2.000 versioni di questa canzone, in tutte le lingue

del mondo, ma quella più famosa rimane sempre quella di Sinatra,

questo perché unisce il background dell‟artista a quello socio-culturale

dell‟America di quegli anni.

Passiamo ora ad analizzare i due testi.

~ 21 ~

VERSIONE FRANCESE – CLAUDE FRANḈOIS

Je me lève et je te bouscule

Tu n'te réveilles pas, comme d'habitude

Sur toi je remonte le drap

J'ai peur que tu aies froid, comme d'habitude

Ma main caresse tes cheveux

Presque malgré moi, comme d'habitude

Mais toi tu me tournes le dos

Comme d'habitude

Alors, je m'habille très vite

Je sors de la chambre, comme d'habitude

Tout seul, je bois mon café

Je suis en retard, comme d'habitude

Sans bruit, je quitte la maison

Tout est gris dehors, comme d'habitude

J'ai froid, je relève mon col

Comme d'habitude

Comme d'habitude, toute la journée

Je vais jouer a faire semblant

Comme d'habitude je vais sourire

Comme d'habitude je vais même rire

Comme d'habitude enfin je vais vivre

Comme d'habitude

Et puis, le jour s'en ira

Moi je reviendrai, comme d'habitude

Toi, tu seras sortie, pas encore rentrée

Comme d'habitude

Tout seul, j'irai me coucher

Dans ce grand lit froid, comme d'habitude

Mes larmes, je les cacherai

Comme d'habitude

Mais comme d'habitude, même la nuit

Je vais jouer a faire semblant

Comme d'habitude, tu rentreras

Comme d'habitude, je t'attendrai

Comme d'habitude, tu me souriras

Comme d'habitude

Comme d'habitude, tu te déshabilleras

~ 22 ~

Oui comme d'habitude, tu te coucheras

Oui comme d'habitude, on s'embrassera

Comme d'habitude

Comme d'habitude, on fera semblant

Comme d'habitude, on fera l'amour

Oui comme d'habitude, on fera semblant

Comme d'habitude

Come si può notare, il titolo della canzone, che significa “come al

solito”, è anche il leitmotiv del testo, che non presenta né rime né una

struttura regolare. Non ci sono dei veri versi, né tantomeno un vero

ritornello, bensì una struttura che gli somiglia. La canzone è chiaramente

autobiografica, come si evince già dalla prima parola (Io), cantata a

cappella. L‟intensità della voce è dolce, ma in contrapposizione con la

gioia della strumentazione: la chitarra, lo xilofono e la batteria lo

rendono quasi un brano gioioso. La melodia nei versi è abbastanza

semplice, sale per poi riscendere, senza mai raggiungere note alte. Tutto,

però, cambia durante il ritornello: si aggiungono gli ottoni e il crescendo

musicale accompagna la voce verso l‟inevitabile acuto. Tutto ciò serve a

distinguere le due tematiche principali, diverse nei versi e nel ritornello.

Nei versi descrive la sua solitudine che prova quando si trova con la sua

compagna, mentre nel ritornello ciò che avviene nella sua vita sociale.

Anche se il “come al solito”, ripetuto così tante volte crea quasi un

distacco da questo contrasto, perché durante tutta la canzone il

protagonista si lamenta di questa sua lenta, monotona vita che sembra

~ 23 ~

non farlo più vivere, al punto in cui deve portare una maschera non solo

con gli altri, ma anche con se stesso. Il ritornello, però, con la sua

struttura armonica movimentata, il crescendo e la curva melodica

ascendente assomiglia più ad un grido di aiuto, di disperazione, di

ribellione. Questo, in parte, si spiega anche con la storia che c‟è dietro

alla canzone, perché a scrivere il ritornello è stato lo stesso Claude

François, che aveva appena rotto con France Gall, sua compagna con cui

aveva una relazione da tre anni. Questo testo è completamente diverso

da quello della versione di Sinatra, che è stata scritta apposta per il suo

personaggio, ma non direttamente da lui.

VERSIONE AMERICANA – FRANK SINATRA

And now, the end is near;

And so I face the final curtain.

My friend, I'll say it clear,

I'll state my case, of which I'm certain

I've lived a life that's full.

I've traveled each and ev'ry highway;

But more, much more than this,

I did it my way.

Regrets, I've had a few;

But then again, too few to mention.

I did what I had to do

And saw it through without exemption.

I planned each charted course;

Each careful step along the byway,

But more, much more than this,

I did it my way.

~ 24 ~

Yes, there were times, I'm sure you knew

When I bit off more than I could chew

But through it all, when there was doubt

I ate it up and spit it out.

I faced it all and I stood tall

And did it my way

I've loved, I've laughed and cried

I've had my fill; my share of boozing.

And now, as tears subside

I find it all so amusing.

To think I did all that;

And may I say - not in a shy way,

No, oh no not me,

I did it my way.

For what is a man, what has he got?

If not himself, then he has naught

To say the things he truly feels

And not the words of one who kneels

The record shows I took the blows

And did it my way

Come si nota già da una prima lettura, il significato del testo è

completamente differente e il suo successo è dovuto proprio a questo

fatto. Questa canzone ha avuto così tanto successo, e continua ancora ad

averne, proprio perché è stata cantata dal cantante giusto, al momento

giusto.

Parla di un uomo che si è fatto da solo, e Frank Sinatra incarna il

mito del sogno americano. La canzone si apre con una frase che potrebbe

far pensare alla fine della vita di uomo (And now the end is near), ma in

realtà Paul Anka la scrisse perché Sinatra aveva deciso di lasciare il

~ 25 ~

mondo della musica, ormai i suoi brani facevano fatica ad entrare in

classifica ed essere un Crooner non attirava più molto il pubblico,

dopotutto quelli sono gli anni del boom dei Beatles. Quindi, il testo parla

dello stesso Sinatra che sa che la fine della sua carriera sta per arrivare,

ma non ha alcun rimpianto, perché sa che ha fatto tutto a modo suo.

Sinatra la cantò esattamente come ci si aspettava da lui, ma tutto questo

solamente grazie al testo di Paul Anka, che si mise nei suoi panni e cercò

di fargli cantare delle parole che fossero credibili, con un linguaggio

anche un po‟ forte, volendo (I ate it up and spit it out). La melodia anche

è stata cambiata, i versi presentano delle rime e la strumentazione non da

più un senso di gioia. Il ritornello, con quel crescendo funziona meglio

con le celebri parole I did it my way, che gli donano quasi un‟aria da

inno generazionale, piuttosto che un grido di disperazione.

La cultura americana si basa sul mito del cosiddetto self-made

man e questa canzone ne incarna a pieno lo spirito. Il suo successo è

dovuto al fatto che a cantarla sia stato proprio Frank Sinatra, che le ha

consegnato

un

ulteriore

significato

emotivo.

Inoltre

incarna

perfettamente anche lo spirito evocativo della musica popolare,

risvegliando in milioni di persone in tutto il mondo quella voglia di

rivalsa, nonostante tutti gli errori che si sono commessi e quella capacità

di dire che, nonostante tutto, ce la si è fatta da soli.

~ 26 ~

4. Approccio pratico alla traduzione

musicale

Nei capitoli precedenti abbiamo osservato come un approccio

socio- semiotico sia importante al fine di trasformare una semplice

traduzione in una hit memorabile. Ma quali sono gli aspetti pratici della

traduzione musicale? Come si fa a far sì che la propria traduzione sia

cantabile una volta terminata? Un altro compito del traduttore, oltre a

quello di far sì che la canzone sia adatta al pubblico della target

language, è quello di riconoscere lo scopo pragmatico di una traduzione

musicale, ovvero che questa canzone sia orecchiabile, verosimile, e

soprattutto cantabile.

~ 27 ~

4.1 Primo approccio alla traduzione

Un metodo molto utile nella traduzione musicale è quello elaborato

dal professor Alfredo Rocca (traduttore, musicista e docente presso la

SSML Gregorio VII di Roma, nonché uno dei pochi in Italia che si

occupa di questo campo), ma non ancora codificato in un libro.

Questo metodo, che è stato illustrato durante il corso di traduzione,

si rivolgeva a studenti senza alcuna esperienza nella traduzione musicale,

e si articola in tre “step”:

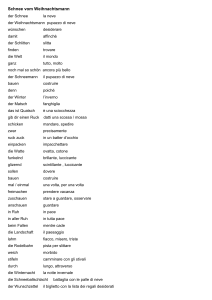

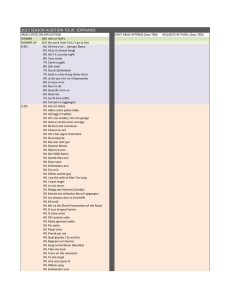

Il primo step consiste nella traduzione semantica del testo, così

da avere chiaro il significato di ogni singolo verso (e quindi anche

dell‟intero brano);

il secondo step, più complesso, prevede il conteggio delle

sillabe dei versi del testo di partenza e l‟identificazione degli accenti in

ogni verso;

il terzo passaggio, tenendo conto della traduzione semantica, del

numero di sillabe, degli accenti dei versi e delle rime, consiste

nell‟elaborazione creativa di soluzioni traduttive cantabili nella lingua

di arrivo.

~ 28 ~

Questo metodo prevede la creazione di una tabella composta da tre

colonne (vedi schema sotto); la prima contiene il testo originale ed il

numero delle sillabe, la seconda la traduzione semantica e la terza la

versione cantabile. Grazie a questo schema è possibile avere sempre

“sotto controllo” il testo originale, evitando quindi di superare quel

confine sottile tra traduzione di un brano ed il suo “rifacimento” in

un‟altra lingua.

Per ottenere risultati accettabili, ovviamente, è necessaria molta

pratica. Si tratta infatti di un metodo di tipo induttivo che, invece di

essere rivolto agli addetti ai lavori, mira a permettere a ogni aspirante

traduttore di elaborare le proprie “regole di lavoro” in modo creativo.

TESTO ORIGINALE

TRADUZIONE

SEMANTICA

~ 29 ~

TRADUZIONE

CANTABILE

4.2 La teoria dello Skopos

Hans J. Vermeer, linguista tedesco nonché studioso nel campo

della traduzione, afferma che la traduzione ha dei riceventi e degli scopi

specifici in determinate situazioni e nel suo famoso libro Towards a

general theory of translational action: Skopos theory explained15, scritto

a quattro mani con Katharin Reiβ, getta le fondamenta per una delle

teorie più rilevanti nel campo della traduzione degli ultimi anni: la

Teoria dello Skopos. Questa, è una teoria generale, ma iperculturale,

ovvero applicabile virtualmente a tutte le culture. La sua mente di

funzionalista lo ha portato a pensare al fatto che ogni traduzione ha

bisogno di uno scopo e che ogni traduttore deve portare a termine il suo

lavoro con questo scopo ben fissato in mente. Lo scopo può essere anche

più di uno, ma l‟importante è che sia ben chiarito quando il lavoro viene

commissionato al traduttore, che, assumendo il ruolo di esperto di un

determinato campo a cui ci si affida, provvederà a svolgere tutto il lavoro

e a decidere quale ruolo il source text gioca nello svolgimento del suo

lavoro. Lo skopos è quasi sempre funzionale ai bisogni e alle aspettative

del pubblico.

15

Vermeer, Hans J., Grundlegung einer allgemeinen Translationstheorie. Tübingen, Niemeyer, 1984.

~ 30 ~

La teoria dello skopos permette al traduttore di lavorare con libertà

e di prendersi le proprie responsabilità per l‟approccio scelto. Il source

text non è più sacro, ma solo un punto di partenza per raggiungere un

obiettivo, un fine. Il fine della traduzione non è più deducibile dal source

text, ma dipende dalle aspettative e dai bisogni del pubblico. In pratica, il

modo in cui il target text deve essere percepito regola quale strategia di

traduzione è la più favorevole.

Esistono tre tipi scopi generali, fondamentali:

A.

Lo scopo generale

B.

Lo scopo comunicativo

C.

Lo scopo strategico

Nel caso della traduzione musicale, quello interessa è lo scopo

strategico, ovvero quello che si pone l‟eterna domanda: in questo caso è

più adatta una traduzione letterale o una più libera? Visto che un altro

skopos della traduzione musicale è quello della cantabilità, la traduzione

sarà più libera, perché deve sottostare a più criteri.

In altre parole, la strategia di traduzione viene determinata dalla

funzione che si intende dare al target text, che potrebbe anche non essere

la stessa del source text. Ovvero, siccome il target text è un testo crossculturale, potrebbe assumere un significato socio-linguistico differente in

~ 31 ~

un differente contesto socio-culturale; rendendo cosi l‟obiettivo di avere

un unico testo perfetto inutile, perché per un solo source text ci possono

essere molti altri target text, tutti ugualmente validi a seconda del loro

skopos.

Questo concetto è applicabile soprattutto alla canzone, dove un

brano originale può avere più di una cover e tutte possono avere lo stesso

successo, perché quest‟ultimo viene determinato oltre che dalle regole

sociali, anche dalla sua cantabilità, lo skopos massimo.

~ 32 ~

4.3 Osservazioni

Lo skopos della cantabilità è uno dei più temibili nel campo della

traduzione, perché ci sono molti limiti imposti dalla musica del source

text, con tutti i suoi aspetti complessi, come il ritmo. Inoltre, nella

musica popolare sono spesso presenti anche delle rime, che sono quasi

una parte fondamentale della musica di questo genere. In pratica, il

compito del traduttore è quello di dare l‟illusione che la musica sia stata

creata apposta per il target text, invece che per adattare le scelte

linguistiche del source text. C‟è anche da prendere in considerazione la

cultura d‟arrivo della canzone, il pubblico che la ascolterà, le loro

capacità di comprenderla e la loro situazione in un polisistema culturale

completamente diverso.

Date tutte queste incognite da risolvere, sarebbe imprudente

scegliere uno skopos di fedeltà massima all‟autore del testo. È molto più

saggio, invece, scegliere un approccio che permetta di fare un buon

lavoro e che quindi lasci maggiori libertà per quanto riguarda il target

text.

~ 33 ~

Visto che l‟obiettivo di una canzone è quello di essere cantata con

una musica già esistente, ad un pubblico che conosce la lingua d‟arrivo,

che ascolterà la canzone per un periodo molto breve (due o tre minuti), ci

si aspetta che porre l‟accento sull‟importanza di alcuni aspetti, piuttosto

che altri, aiuterà il traduttore ad organizzare meglio il lavoro e dare la

priorità a cosa è davvero importante e a cosa invece è sacrificabile.

La canzone è un complesso sistema che unisce due dei più

complicati codici esistenti: la musica e la parola. Quando si va a tradurre

non si tratta più di una semplice azione linguistica, perché la musica con

il suo potere evocativo, funge da messaggio non verbale; ed è per questo

motivo che, anche chi non conosce l‟inglese, può comunque affermare di

aver afferrato il concetto della canzone. Tutto ciò sarà ancora più vero

per quelle canzoni che vengono definite musico-centriche, dove il

messaggio musicale è quello più importante, rispetto alla controparte

logo-centrica, dove ciò che conta è il testo.

Solitamente, uno dei due codici precede l‟altro. Non è difficile che

il source text sia stato scritto prima che la musica venisse ancora

composta. Se ci si pensa bene, in questo caso, si può parlare di un atto di

traduzione anche da parte del compositore, che ha cercato di tradurre in

musica le parole di una canzone, per fare in modo che il messaggio non

~ 34 ~

venisse trasmesso solamente tramite la parola, ma anche grazie alle note.

Il compito del compositore è quello di trovare una melodia che centri il

messaggio che lo scrittore vuole mandare e che riesca anche ad

ampliarlo. Ovviamente il traduttore dovrà lavorare attenendosi sia al

lavoro dello scrittore, che a quello del compositore. In pratica dovrà

trovare in un‟altra lingua e con nuove parole un messaggio simile a

quello del source text che vada bene anche con una musica pre-esistente.

L‟unica consolazione, è appunto che questo lavoro, nel caso in cui lo

scrittore e il compositore sono diversi, è già stato affrontato da colui che

ha fatto gli arrangiamenti, che a sua volta ha già fornito una sua

interpretazione del source text. Questa è una delle grandi differenze che

la traduzione musicale ha con un campo molto affine, quello della

traduzione poetica. Nella traduzione poetica, se un poesia è mal tradotta

si nota subito e molti traduttori sono stati tacciati di aver rovinato delle

vere e proprie opere d‟arte. Mentre per quanto riguarda la traduzione

musicale, il traduttore è, in un certo senso, coadiuvato dal compositore

che ha già effettuato un lavoro simile al suo in precedenza e, inoltre,

anche da un buon performer; se un cantante ha una forte presenza

scenica e una personalità molto spiccata, gli errori presenti nel target text

passeranno in secondo piano, perché il pubblico avrà un terzo codice da

~ 35 ~

cui attingere: il linguaggio del corpo del performer. Quindi, il target text,

in una situazione ideale, gode di tanti aiuti che lo rendono migliore.

Ovviamente, la traduzione musicale non è una scienza esatta. Ci

vuole molto esercizio per riuscire ad entrare nel meccanismo e per

riuscire a lottare contro le idiosincrasie della target language. Per questo

motivo, anche chi ha scelto e sceglie di intraprendere questo percorso,

raramente affronta il problema in saggi o scrive tesi sul come farlo. Non

esiste una guida che imponga delle regole su come tradurre una canzone,

né tantomeno un unico metodo. Molti ricorrono a vari escamotage per

raggiungere il proprio skopos, non solo la parafrasi e la trasposizione, ma

anche l‟omissione di alcune parti, l‟adattamento culturale, le equivalenze

stilistiche, la soppressione di versi troppo difficili, l‟aggiunta di parole a

causa di problemi ritmici o il rimpiazzo di rime con assonanze e

consonanze. Il traduttore Andrew Kelly è uno dei pochi che si è

prefissato dei punti che aiutano a capire con quale spirito bisogna

affrontare la traduzione.

1.

Rispettare il ritmo,

2.

Capire e rispettare il significato,

3.

Rispettare lo stile,

4.

Rispettare le rime,

~ 36 ~

5.

Rispettare il suono,

6.

Rispettare le proprie scelte di pubblico prefissato,

7.

Rispettare l‟originale.

Tutti questi punti sono ciò a cui un traduttore dovrebbe ambire per

riuscire a svolgere la perfetta traduzione. La cosa buona è che per

riuscire a rispettarli, Kelly non dà alla parola rispettare una connotazione

rigida, bensì una abbastanza flessibile, così da riuscire a raggiungere lo

skopos che ci si era prefissati senza troppi problemi.

Altri consigli arrivano invece da Richard Dyer Bennet, che ha

tradotto in inglese l‟opera di Schubert Die schöne Müllerin. Più che

consigli, Bennett offre quattro differenti skopos per una traduzione:

1.

Il target text deve essere cantabile,

2.

La musica deve sembrare cucita addosso al target

text, anche se è stata composta per il source text,

3.

Lo schema

metrico dell‟originale deve essere

mantenuto, perché dà forma alle frasi,

4.

Il traduttore deve prendersi delle libertà con il

significato originale nel caso in cui i tre punti precedenti non

possano essere raggiunti altrimenti.

~ 37 ~

La prima linea guida è quasi ovvia. Ogni canzone, per principio,

deve essere cantabile, altrimenti qualsiasi altra sua caratteristica è inutile.

Il secondo punto assume che ci sia una stretta relazione tra musica e

testo; una relazione talmente stretta che deve essere preservata anche in

un‟eventuale traduzione. Il terzo punto, invece, non è applicabile a tutte

le canzoni, perché lo schema metrico e delle rime può essere conservato

in alcune traduzioni, mentre in altre deve essere per forza di cose

modificato, anche se la rima è sempre un buon modo per dare forma ad

un testo. Se ci si pensa, quando si recita, le rime sono uno degli effetti

che colpisce di più l‟ascoltatore, ma per quanto riguarda le canzoni non è

così, delle parole in rima possono avere anche dieci secondi di distanza

l‟una dall‟altra in una canzone, e ciò diminuisce il loro impatto sul

pubblico. Oltretutto, il loro effetto verrebbe sottomesso anche dalla

melodia e dall‟armonia in una canzone. Il quarto punto, invece, fa capire

che tutti i punti precedenti sono molto importanti e che per rispettarli ci

si possono prendere anche delle piccole libertà semantiche.

Alla fine, questo compito non sarebbe possibile senza prendersi

alcune libertà. Non bisogna, quindi, chiudersi nella rigidità del rispetto

delle regole che possono essere applicate ad altri campi, ma non a

questo. Ogni tanto lasciare la finestra aperta a delle nuove libertà, può

portare un po‟ di aria fresca. Basta pensare alle ripetizioni presenti in un

~ 38 ~

testo in inglese, dove sono molto comuni. Un traduttore che segue

rigidamente le regole e si avvale di una strategia che dà troppa

importanza al source text, lo tradurrebbe sempre con le stesse parole, non

effettuando variazioni. Questo non è sbagliato, ma in italiano il testo

diventa troppo statico e le ripetizioni andrebbero evitate, se possibile.

Quindi, un traduttore più flessibile, libero di prendersi le proprie piccole

libertà, potrebbe decidere di trovare delle soluzioni alternative. La

ricchezza semantica guadagnata dal target text sarà sicuramente

maggiore della perdita di una ripetizione strutturale.

~ 39 ~

4.4 Il Principio Pentathlon

Low è uno degli studiosi che più ha contribuito alla ricerca sulla

traduzione musicale. Il suo contributo maggiore alla causa è stato proprio

il Principio Pentathlon, un approccio alla traduzione che ha come base la

teoria dello skopos. Viene chiamato Principio Pentathlon perché si basa

sull‟equilibrio dei cinque diversi aspetti che devono venire presi in

considerazione quando si effettua una traduzione musicale: la cantabilità,

il senso, la naturalezza, il ritmo e le rime. Il nome è una metafora, che

paragona i pentatleti ai traduttori. Nel pentathlon gli atleti devono

concorrere in cinque diverse competizioni sportive e devono riuscire ad

ottimizzare il loro punteggio medio, per questo motivo spesso decidono

di arrivare secondi o addirittura terzi in un singolo evento per poter

mantenere la concentrazione e, soprattutto, le energie per le altre gare.

La loro qualità principale, come quella di un traduttore, deve essere la

flessibilità.

Così come i pentatleti, anche il traduttore deve competere in

cinque “categorie” differenti e deve riuscire ad ottenere un buon risultato

totale, senza concentrarsi troppo su solamente uno degli aspetti o

tralasciandone altri che potrebbero sembrare meno importanti. Peter Low

~ 40 ~

suddivide anche i primi quattro aspetti in “doveri del traduttore”. La

cantabilità è il dovere del traduttore al cantante, il senso all‟autore del

testo, la naturalezza al pubblico, mentre il ritmo al compositore. Per

quanto riguarda le rime, invece, le tratta come un caso speciale.

4.4.1

Cantabilità

Sebbene anche secondo Low si tratti di un criterio quasi ovvio,

merita sicuramente la prima posizione in questo campo, perché

rappresenta lo skopos primario della traduzione. Anche perché il

cantante, o chi per lui commissiona la traduzione di una canzone, vuole

un prodotto usabile, da poter vendere.

Perciò il target text deve

funzionare bene con la musica, e deve poter essere compreso anche ad

una velocità più sostenuta, perché il pubblico che lo ascolterà non avrà il

tempo di riflettere sulle parole. Ciò significa che deve andare a braccetto

con la musica, se si ha una canzone più lenta, con una melodia triste, il

testo non potrà essere allegro. Alcune canzoni cercano di far emozionare

il pubblico, altre invece vogliono semplicemente far divertire.

Anche una persona non esperta di musica riesce a capire se una

canzone è cantabile o meno: basta far coincidere gli accenti linguistici

~ 41 ~

con quelli musicali, perché una canzone con gli accenti sbagliati non

può mai essere suonata in modo soddisfacente. 16 In italiano ci sono molti

“trucchi” per riuscire a far coincidere gli accenti, come la doppia

accentazione di parole sdrucciole o semisdrucciole, utilizzabili in metrica

sia come sdrucciole che come piane. Spesso, le frasi musicali terminano

con l‟accento sull‟ultima nota e i traduttori sono costretti ad usare un

monosillabo, o una parola tronca. Un esempio di come poter risolvere

questo problema ce lo da Mogol, che però appartenendo ad una vecchia

generazione di traduttori stravolge il significato del testo, a favore della

cantabilità.

The thunder cracks against the night

La notte cade su di noi

The dark explodes with yellow light

la pioggia cade su di noi

The railroad sign is flashing bright

la gente non sorride più

The people stare but I don‟t care

vediamo un mondo vecchio che

My flesh is cold against the bone

ci sta crollando addosso ormai

And Cheryl‟s going home.

ma che colpa abbiamo noi?

(Bob Lind, Cheryl‟s going home, 1966)

(The Rokes, Che colpa abbiamo noi?, 1966)

L‟accento obbligato in ultima sede mette i traduttori di fronte ad

una scelta obbligata, quella che negli scacchi si chiama Zugzwang, e che

in linguistica viene definita, più semplicemente, mossa obbligata. Per

riempire quella casella bisogna ricorrere a un ristretto novero di

16

Il cantautore. Guida per gli aspiranti alla carriera di autori- cantanti di musica leggera. 1964.

~ 42 ~

soluzioni. Oltre alle soluzioni presentate sopra, spesso si ricorre anche

all‟utilizzo di alcune voci del passato remoto, del futuro e del

condizionale. I primi due, però, sono molto arcaici, quello più ambito è

sicuramente il futuro, sfruttato non solo dai traduttori verso l‟italiano, ma

anche dagli stessi cantautori.

Un altro aspetto della cantabilità è l‟evidenziazione di determinate

parole nel source text per alcuni fini musicali, per esempio potrebbero

essere segnate fortissimo, o semplicemente cantate in falsetto. In questo

caso, il compositore gli sta dando un‟importanza particolare, e

dovrebbero, idealmente, essere tradotte nello stesso posto, altrimenti si

potrebbe perdere il focus del verso, facendo cadere l‟evidenziazione su

di un‟altra parola.

4.3.2 Senso

Quando si traducono dei testi informativi, il senso è l‟aspetto più

importante della traduzione. Quando si passa alla traduzione musicale,

~ 43 ~

però, le sue varie sfaccettature ci impongono dei piccoli cambiamenti

che serviranno a rendere la canzone più cantabile.

Il significato non viene completamente accantonato, rimane

sempre un aspetto molto importante; ma la definizione di accuratezza

non è la stessa rispetto alle altre traduzioni, perché tende ad allentarsi un

po‟. Infatti, una parola può essere rimpiazzata con un suo sinonimo, una

metafora con un‟altra che svolga più o meno la stessa funzione in quel

contesto. Ciò succede perché questo è un campo in cui la conta sillabica

è molto importante per rientrare nel ritmo del source text ed è meglio

sostituire una parola, piuttosto che cambiare la melodia della canzone.

Il senso, però, si trova al secondo posto nella classifica

immaginaria di Low, perché molti, come era solito accadere in passato,

continuano a stravolgere completamente il senso di una canzone,

rimpiazzando il source text con un target text completamente diverso,

che si adatta semplicemente alla musica già esistente. Ma in questo caso

stiamo parlando di traduzioni e tradurre significa riportare il senso di un

testo in un‟altra lingua.

4.3.3 Naturalezza

~ 44 ~

Questo aspetto include altri aspetti della target language, quali

registro e ordine delle parole. Viene associato da Low come il dovere del

traduttore verso il pubblico. L‟autore decide di mettere la naturalezza al

terzo posto di questa classifica, perché pensa che molti testi da lui presi

in analisi siano privi di un ordine logico di parole, il che porta a pensare

che sia impossibile fare una buona traduzione musicale.

Questa considerazione riporta all‟eterno dibattito: è giusto che si

nasconda al pubblico che un testo è stato tradotto? In realtà, il traduttore

di canzoni non dovrebbe porsi queste domande, perché la musica è un

campo particolare e un testo di una canzone si gioca tutte le sue carte

durante il primo ascolto. Ciò fa sì che la naturalezza della lingua sia di

primaria importanza. Un‟eventuale innaturalezza, con un conseguente

spostamento di parole per far trasparire solamente la precisione

semantica, richiederebbe uno sforzo maggiore da parte del pubblico. Il

target text non dovrebbe essere tradotto, a meno che non possa essere

capito ad un primo ascolto. Per le canzoni, il tempo di comprensione non

può essere allungato quanto e come si vuole, come accade per la poesia,

in cui una persona può fermarsi e cercare di capire meglio il testo. Non si

devono evitare a tutti i costi gli spostamenti di parole all‟interno della

frase, ma sarebbe meglio restringerli a quando sono strettamente

necessari, per evitare di appesantire il target text.

~ 45 ~

4.3.4 Ritmo

In una canzone, la musica ha il suo ritmo specifico, che determina

il ritmo con cui il source text verrà cantato. Il dovere del traduttore al

compositore è quello di portare rispetto alla sua creazione, rispettandolo

quando si va a tradurre.

Molti studiosi, tra cui troviamo Eugene Nida e Frits Noske,

pensano che la difficoltà del far combaciare il ritmo, sia solo un

problema di conteggio delle sillabe; ad esempio un verso di otto sillabe

deve essere tradotto con un altro verso di otto sillabe.

Questo obiettivo è sicuramente il più auspicabile, ma impone

troppa rigidità al traduttore. I compositori del „900 erano soliti apportare

piccoli cambiamenti al ritmo di alcuni versi, dopotutto anche gli stesi

compositori moderni spesso apportano delle modifiche al ritmo per far

combaciare al meglio la musica con il testo.

Anche secondo il Principio Pentathlon una identica conta sillabica

significherebbe la perfezione, ma non se la naturalezza del testo ne

dovesse risentire. Quindi, un traduttore flessibile può scendere a

compromessi e decidere di aggiungere o sottrarre una sillaba, a seconda

~ 46 ~

del caso. Un buon momento per apportare un cambiamento del genere

potrebbe essere un pezzo più recitato che cantato, dove il cantante

riuscirebbe a giostrarsi meglio e a mascherare una modifica con la sua

presenza scenica.

Secondo Low, invece, sarebbe meglio aggiungere una sillaba in un

melisma17, mentre il miglior posto per sottrarre una sillaba sarebbe su

una nota ripetuta, perché questi metodi alterano il ritmo senza però

disturbare la melodia.

Anche i cambiamenti di melodia, però, sono effettuabili. È sempre

meglio cambiare leggermente un po‟ di melodia, piuttosto che avere una

frase con un ordine innaturale delle parole. Non si tratta di cambiare

totalmente la melodia, ma di rispettare la canzone in generale,

modificando leggermente l‟aspetto più sacrificabile in una determinata

situazione di impaccio.

In alcuni casi, il target text potrebbe anche mancare alcune sillabe,

o perché il source text usa molte parole corte, o perché una prima bozza

del target text è molto concisa. Allora, il traduttore deve decidere se è

meglio aggiungere una parola, o una frase, che sia sempre in linea con il

17

Nella musica vocale, viene detto melisma quel tipo di ornamentazione melodica che consiste nel

caricare su di una sola sillaba un gruppo di note ad altezze diverse. La vocale della sillaba viene

spalmata sulle varie note, cantata modulando l‟intonazione ma senza interrompere l‟emissione vocale.

~ 47 ~

senso del testo, o semplicemente tagliare alcune note dallo spartito.

L‟opzione migliore, ovviamente, è sempre la prima, per rispetto verso il

compositore dell‟opera e perché una parola, se aggiunta con giudizio,

non cambia il senso del testo. La parola aggiunta deve sempre essere ben

studiata e non deve dare l‟impressione di essere un‟aggiunta. Questo può

succedere con gli aggettivi: invece di usarne solamente uno, se ne

possono usare due molto simili tra loro di significato, in modo che il

testo della canzone non venga modificato.

In ogni caso, la conta sillabica in sé, non è un metodo molto

accurato per misurare il ritmo di una canzone, perché non è come lo

schema metrico delle poesie. Bisogna sempre tenere a mente che il testo

deve essere cantato e si deve prestare attenzione anche alla lunghezza

delle note, che possono variare da una croma ad una semi-breve. Il

compito del traduttore non è quello di creare una copia perfette del

source text nella target language, ma di creare un target text che vada

bene per la musica che si ha e che, soprattutto, rispetti lo skopos di

essere cantabile. Per questo motivo, il consiglio di Low è di stare attenti

alla lunghezza delle vocali, senza però dimenticare l‟importanza delle

consonanti, che sono molto importanti nella canzone italiana.

~ 48 ~

4.3.5 Rime

Questo è lo scoglio che rende la traduzione musicale il mostro

nero delle traduzioni. In realtà succede solamente perché molti traduttori

danno fin troppa importanza alle rime.

Il Principio Pentathlon funziona molto bene per quanto riguarda

questo aspetto, perché si oppone alla rigidità di pensiero ed è a favore di

una maggiore flessibilità. Nel caso in cui le rime possono essere

eliminate senza alcune ripercussione sul target text, molti traduttori

fanno bene ad eliminarle completamente, perché non sono una parte

importante, non danno forma al testo, come invece afferma Richard

Dyer- Bennet; ci pensa il ritmo a dare forma alla canzone.

Ovviamente, ci sono casi in cui questo tipo di approccio non

funziona, e qui appare in soccorso il Principio Pentathlon, che offre al

traduttore di riuscire a mantenere tutte le rime che ritiene giusto, senza

però imporre come modello lo schema del source text.

~ 49 ~

Conclusioni

Nella mia tesi ho cercato di elencare le caratteristiche della cultura

popolare e delle comunicazioni di massa che influenzano notevolmente

la musica popolare e la sua traduzione. I concetti di mediazione ed

approccio semiotico si sono provati utili per analizzare in maniera più

approfondita i cambiamenti che avvengono durante il processo di

traduzione. Questi studi non si concentrano più solo sull‟aspetto

linguistico della traduzione, ma includono anche la sua componente

sociale, anche se ancora non è abbastanza per poter sviluppare dei

metodi adatti. La semiotica permette di fare una valutazione delle

interazioni e dell‟interdipendenza dei vari elementi che compongono la

traduzione di tipo musicale

e potrebbe fornirci un migliore

apprendimento di quale siano il suo ruolo e la sua influenza nel mondo

della musica. Le canzoni popolari sono sicuramente una sfida per

chiunque decide di addentrarsi in questo campo, ma non scordiamoci che

con nuove teorie pratiche, come quella dello skopos e il Principio

Pentathlon, si può facilitare questo immenso compito. La flessibilità che

questi due approcci concedono, permette al traduttore di lavorare

secondo i suoi principi e di riuscire a fare un buon lavoro generale, senza

~ 50 ~

che si preoccupi troppo di ottenere l‟eccellenza in ogni singolo campo

che va a comporre il processo di traduzione.

~ 51 ~

~ 52 ~

English Section

~ 53 ~

~ 54 ~

Introduction

Even if music is an important part of our everyday lives, it has

largely been neglected by academics in translation studies. Music is not

just a hobby, but also a powerful mass media that is able not only to

influence costumes and practices, but also the wishes of a community.

We can‟t live without listening to music, it follows us everywhere we go:

shops, restaurants, pubs, clubs, railways and underground stations. It‟s

part of our daily lives also under visual form, in TV and concerts, for

example.

Song translation is seldom taught and there aren‟t as many studies

as for the other translation fields, even though there are

numerous

translations available. Why it is so hard to find a study on song

translation, then? The answer to this question is not too hard to find:

song translation is not a real translation. It includes a wide range of other

factors as well. Translations do not have to take into consideration only

the aspects of rhythm, time, tone or rhyme, but social and cultural

aspects as well, especially if what is to be translate is a pop song.

~ 55 ~

1. Studies on Song Translation

The few studies we have at hand give relatively little attention on

song translation itself. And, most of all, what is missing is a sociosemiotic research; what is taken for granted is that song meanings, and

translations, are only important at a linguistic level. To better understand

the changes that occur in the process of translation one needs to widen

the perspective and study the social and cultural context in which a given

song, or its translation, is successful.

Then, how is it possible to deal with a translation taking into

account both semiotics and the target culture? A socio- semiotic

approach has been developed by Itamar Even- Zohar, Gideon Toury and

Theo Hermans. The basic idea behind their study is that one has to see

translation as a series of interdependent texts, enclosed in many

subsystems that form a more complex polysystem. Sounds difficult? It is

not! In this framework, translations show characteristics that are the

result of the interrelations taking place between the other texts found in

this system. So, translations, whether one observes the function or the

product, can only be studied in a relational manner; that is, the individual

and distinctive characteristics of a translation in a specific genre or at a

~ 56 ~

specific time in history, can only be determined in the context of these

relations. It is only thanks to the cultural background that a work gains

its value.

Even- Zohar‟s approach is similar to a binary system, because it is

based primarily on two things: a center and a periphery. At the centre,

we can find the most prestigious works of art and genres.

In the

periphery, however, one can find the forms of the so-called “low”

literature and everything is far less organized than the centre.

This division between centre and periphery, leads to another two

subdivisions that determine the opposition between canonized and noncanonized products. The importance of a specific work or of a specific

genre is not objective, because it is something bestowed by institutions,

scholars, experts, therefore by people; so this opposition has to be

observed by a social point of view. But what makes a work important?

Its function. And here one can observe another subdivision: this work

has a primary or secondary function? That is to say, this work has an

innovative or conservative function within the system?

This study has been made possible, because in our society literature

is considered as an artifact that represents a system with a systemic

evolution. If one decides to analyse music with such parameters, one

~ 57 ~

could see that pop music belongs to the periphery of this system, because

it is not considered important by everyone and its function is not exactly

innovative, because it just wants to be sold to the masses.

At this point, Evan Zohar‟s theory is not able to give us other

answers, even though it offers us a sort of framework on which we can

ground further reasoning. Here, the innovative concept of

Lambert

comes into play: the design of maps of mass communication that

represent the uses of the different languages in the society. His study on

mass media translation is mostly based on audiovisual, but it is also

relevant for song translating.

If one were to sketch a map, one would see that the production and

distribution of pop music is in the hands of a few majors that can reach

the audience all over the globe. Cartography helps us draw schemes that

help us understand that what is distributed or imported is not a simple

song anymore, but a package containing a certain kind of culture,

language and values. If we apply sociology and take into account

relationships between countries as well, it can be showed that the

country that buys more than it sells, is disadvantaged compared to the

country that sells more than it buys. In this sense, it is not anymore just a

matter of translation, but also an ideological and political issue, because

~ 58 ~

it will be easier to accommodate a country that is more used to a foreign

influence, since it will be accustomed to the source language and source

culture. Meanwhile, it will be harder for the people of a country who

only listens to its own music, in its own language, to fully understand

the message the author of the song in the source language wants to

convey.

What Lambert does not take into consideration is that music is an

object that goes through a mediation process, that is what one must take

into account when translating. Negus and Hennion acknowledge three

kinds of mediation:

1.

INTERMEDIARY ACTION : it concerns the interaction

between production and consumption of pop music from the audience. It

concerns all the interventions of institutions and persons responsible for

the production, distribution and consumption of music. The various

interventions cannot be perceived as neutral, but function as gatekeeping.

2.

TRANSMISSION: it concerns the impact technology has on

music production, distribution and consumption. Most of all on how the

instruments and the video clips influence the creation and reception of

the text.

~ 59 ~

3.

SOCIAL RELATIONSHIPS: it concerns above all the

ideologies and how those could privilege some interests rather than

others.

All of the above, does not imply that that is the only aspect that

matters, because also the linguistic aspect is important in a translation. It

does not mean that mediation is the only process needed to translate a

song, but it is part of the process that the same song undergoes before

getting to its destination. Popular songs lyrics are inevitably linked to

one another through the characteristics of the music world. Music styles,

music genres, music videos, CD covers, mass media, these are the things

that influence both consumers and artists and are part of the mental

process that induces us to buy or write a song.

~ 60 ~

2. Socio-semiotic analysis

At this point, one last question needs answering. What is the role

that music plays in the socio- cultural process of translation? We know

for sure that music has an evocative and associative power for those who

listen. But, is this power the same both in the target and source

language?

The issue with modern, popular music is that it is perceived as

lacking originality, meaning. Its only purpose is appealing to people, just

to be sold. It exists only to meet existing emotional needs; it does not

leave any room for the singer and addressees‟ personality. Nevertheless,

being devoid of any originality is what makes it so fit to our society,

because the written text and the message that the artist is trying to

convey lose importance. What really matters is that it is suitable for the

addressees. The word “popular” itself underlines its link with the public.

Pop music is so tied to society, that it determines the values shared. As I

previously said, the changes brought to the target text, during the process

of translation cannot be arbitrary, and they cannot be, because they are

imposed by socio-cultural values that determine the cultural transfer.

~ 61 ~

Pop music has grown side by side with technological development

and is produced with the purpose to be sold and cannot be analysed

taking into account only its musical aspect. The musical aspect is of

secondary importance and if one keeps considering only this aspect to be

relevant, then the field of song translation will never bloom, because

what is lacking is the basis needed to create suitable analytic tools.

The scholar Philip Tagg was able to include also the semiotic factor

in his research. He did not observe only rhythm or rhymes, but also

tempo, instrumentation, harmony, accentuation, mechanical, acoustical

and dynamic aspects. Using these guidelines provided by Tagg, we can

move onto analysing a song translated into another language and we can

try to understand why the target text was more successful than the source

text.

~ 62 ~

2.1 Comparison between songs: sociosemiotic and musical analysis.

The translation I would like to analyse is one of the greatest songs

of the last century: My way, sung by Frank Sinatra. It is one of the most

covered songs, but many do not know that Sinatra‟s version is a cover

itself. The original song was Comme d’habitude, sung by the French

artist Claude François. The definite version of the song was composed

by Jacques Revaux and Claude François, who also wrote part of the

lyrics together with Gilles Thibaut. The song was originally written in

English and was called For me, but it was rejected by every singer it

was proposed to. Revaux decided to give it to Claude François, then,

who accepted to sing it, but only if he could rewrite part of the lyrics. So

he introduced the theme of the struggling lovers, taking inspiration from

his relationship with the French actress France Gall.

The song was recorder and published in 1967 and immediately

became a huge hit in France. Claude François even decided to sing an

Italian version of the song, which was not exactly successful and only

came out as a B side of Se torni tu.

~ 63 ~

That same year, the singer and composer Paul Anka was in France

on holiday and heard the song on the radio. As he later confirmed, at first

he did not think the song was any good, but had something to it that

made him go to Paris and buy the rights for an American adaptation.

Once back in America, Anka completely changed the source lyrics,

trying to rewrite it so that it would be perfect for his dear friend Frank

Sinatra. When he was done, the song was no more about a struggling

couple, but about a man who has no regrets, because he has always lived

life his way.

Today, more than 2.000 covers of this song have been recorded all

over the world, but the most famous is still the Frank Sinatra one. But

why?

FRENCH VERSION – CLAUDE FRANḈOIS

Je me lève et je te bouscule

Tu n'te réveilles pas, comme d'habitude

Sur toi je remonte le drap

J'ai peur que tu aies froid, comme d'habitude

Ma main caresse tes cheveux

Presque malgré moi, comme d'habitude

Mais toi tu me tournes le dos

Comme d'habitude

Alors, je m'habille très vite

Je sors de la chambre, comme d'habitude

Tout seul, je bois mon café

~ 64 ~

Je suis en retard, comme d'habitude

Sans bruit, je quitte la maison

Tout est gris dehors, comme d'habitude

J'ai froid, je relève mon col

Comme d'habitude

Comme d'habitude, toute la journée

Je vais jouer a faire semblant

Comme d'habitude je vais sourire

Comme d'habitude je vais même rire

Comme d'habitude enfin je vais vivre

Comme d'habitude

Et puis, le jour s'en ira

Moi je reviendrai, comme d'habitude

Toi, tu seras sortie, pas encore rentrée

Comme d'habitude

Tout seul, j'irai me coucher

Dans ce grand lit froid, comme d'habitude

Mes larmes, je les cacherai

Comme d'habitude

Mais comme d'habitude, même la nuit

Je vais jouer a faire semblant

Comme d'habitude, tu rentreras

Comme d'habitude, je t'attendrai

Comme d'habitude, tu me souriras

Comme d'habitude

Comme d'habitude, tu te déshabilleras

Oui comme d'habitude, tu te coucheras

Oui comme d'habitude, on s'embrassera

Comme d'habitude

Comme d'habitude, on fera semblant

Comme d'habitude, on fera l'amour

Oui comme d'habitude, on fera semblant

Comme d'habitude

As one can see, the title of the song, which means “as usual”, is also

the leitmotiv of the original lyrics, which does not have rhymes or a

regular structure. There is not a real refrain and there is not any verse

~ 65 ~

structure, just something that vaguely looks like it. The song is

autobiographical, as one can understand from the first word “I”, sung a

capella. The voice is sweet, but in opposition against the joy of the

instrumentation: the rhythm of the guitar, the xylophone and the drum

makes it more joyful than it should be. The tune during the verses is

quite simple, it rises just to go back down again, without reaching high

notes. Everything changes during what we can call the refrain: the brass

come into play and the crescendo accompanies the voice toward the

inevitable high note. All this creates a distinction between refrain and

verses. In the verses he describes the loneliness he feels when he‟s with

the woman he loves; in the refrain what happens in his social life, when

he‟s out. The repetition of as usual creates a sort of detachment , because

the singer complains throughout all the song about his slow, lonely, life

to the point that he has to wear a mask not only with the others, but also

with himself. The refrain, though, looks like a cry for help. This can be,

in part, explained with the story behind the song, because it was Claude

François who wrote the refrain, inspired by his story with the French

actress France Gall, with whom he had split up after three years of

relationship.

The source text is completely different from the

Anka/Sinatra version, because that song was written for him, but not by

him.

~ 66 ~

AMERICAN VERSION – FRANK SINATRA

And now, the end is near;

And so I face the final curtain.

My friend, I'll say it clear,

I'll state my case, of which I'm certain

I've lived a life that's full.

I've traveled each and ev'ry highway;

But more, much more than this,

I did it my way.

Regrets, I've had a few;

But then again, too few to mention.

I did what I had to do

And saw it through without exemption.

I planned each charted course;

Each careful step along the byway,

But more, much more than this,

I did it my way.

Yes, there were times, I'm sure you knew