Projects

28

In architettura, la trasparenza

non è negazione della materia

ma solo un radicale cambio di

identità. Attraverso la

trasparenza del volume

architettonico, il processo di

dematerializzazione segue

l’evolversi della tecnologia in

un crescendo che pare non

avere mai fine. Il futuro

dell’architettura sembra

dunque puntare verso il

concetto di spazio globale,

eliminando così la distinzione

fra esterno e interno.

In architecture, transparency is

not a denial of matter; it is simply

a radical change of identity.

Through the transparency of the

architectural volume, the process

of dematerialization follows the

evolution of technology in a

growing development that

appears endless. Therefore, the

future of architecture seems to

point toward the concept of

global space, thereby eliminating

the distinction between internal

and external space.

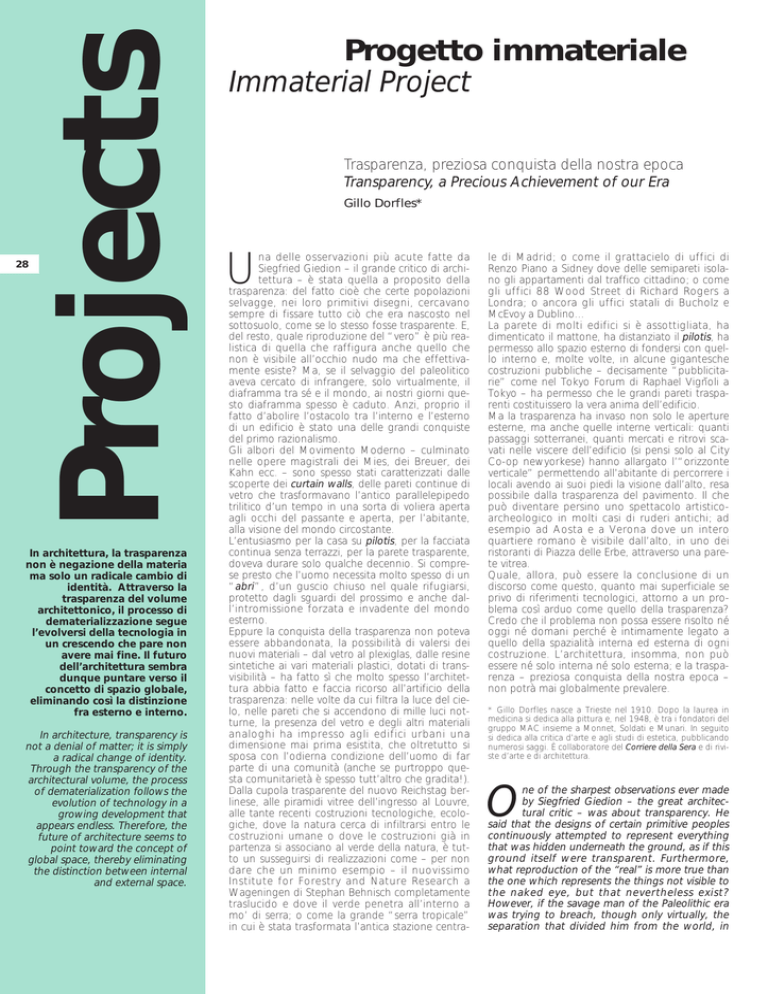

Progetto immateriale

Immaterial Project

Trasparenza, preziosa conquista della nostra epoca

Transparency, a Precious Achievement of our Era

Gillo Dorfles*

U

na delle osservazioni più acute fatte da

Siegfried Giedion – il grande critico di architettura – è stata quella a proposito della

trasparenza: del fatto cioè che certe popolazioni

selvagge, nei loro primitivi disegni, cercavano

sempre di fissare tutto ciò che era nascosto nel

sottosuolo, come se lo stesso fosse trasparente. E,

del resto, quale riproduzione del “vero” è più realistica di quella che raffigura anche quello che

non è visibile all’occhio nudo ma che effettivamente esiste? Ma, se il selvaggio del paleolitico

aveva cercato di infrangere, solo virtualmente, il

diaframma tra sé e il mondo, ai nostri giorni questo diaframma spesso è caduto. Anzi, proprio il

fatto d’abolire l’ostacolo tra l’interno e l’esterno

di un edificio è stato una delle grandi conquiste

del primo razionalismo.

Gli albori del Movimento Moderno – culminato

nelle opere magistrali dei Mies, dei Breuer, dei

Kahn ecc. – sono spesso stati caratterizzati dalle

scoperte dei curtain walls, delle pareti continue di

vetro che trasformavano l’antico parallelepipedo

trilitico d’un tempo in una sorta di voliera aperta

agli occhi del passante e aperta, per l’abitante,

alla visione del mondo circostante.

L’entusiasmo per la casa su pilotis, per la facciata

continua senza terrazzi, per la parete trasparente,

doveva durare solo qualche decennio. Si comprese presto che l’uomo necessita molto spesso di un

“abri”, d’un guscio chiuso nel quale rifugiarsi,

protetto dagli sguardi del prossimo e anche dall’intromissione forzata e invadente del mondo

esterno.

Eppure la conquista della trasparenza non poteva

essere abbandonata, la possibilità di valersi dei

nuovi materiali – dal vetro al plexiglas, dalle resine

sintetiche ai vari materiali plastici, dotati di transvisibilità – ha fatto sì che molto spesso l’architettura abbia fatto e faccia ricorso all’artificio della

trasparenza: nelle volte da cui filtra la luce del cielo, nelle pareti che si accendono di mille luci notturne, la presenza del vetro e degli altri materiali

analoghi ha impresso agli edifici urbani una

dimensione mai prima esistita, che oltretutto si

sposa con l’odierna condizione dell’uomo di far

parte di una comunità (anche se purtroppo questa comunitarietà è spesso tutt’altro che gradita!).

Dalla cupola trasparente del nuovo Reichstag berlinese, alle piramidi vitree dell’ingresso al Louvre,

alle tante recenti costruzioni tecnologiche, ecologiche, dove la natura cerca di infiltrarsi entro le

costruzioni umane o dove le costruzioni già in

partenza si associano al verde della natura, è tutto un susseguirsi di realizzazioni come – per non

dare che un minimo esempio – il nuovissimo

Institute for Forestry and Nature Research a

Wageningen di Stephan Behnisch completamente

traslucido e dove il verde penetra all’interno a

mo’ di serra; o come la grande “serra tropicale”

in cui è stata trasformata l’antica stazione centra-

le di Madrid; o come il grattacielo di uffici di

Renzo Piano a Sidney dove delle semipareti isolano gli appartamenti dal traffico cittadino; o come

gli uffici 88 Wood Street di Richard Rogers a

Londra; o ancora gli uffici statali di Bucholz e

McEvoy a Dublino…

La parete di molti edifici si è assottigliata, ha

dimenticato il mattone, ha distanziato il pilotis, ha

permesso allo spazio esterno di fondersi con quello interno e, molte volte, in alcune gigantesche

costruzioni pubbliche – decisamente “pubblicitarie” come nel Tokyo Forum di Raphael Vign̆oli a

Tokyo – ha permesso che le grandi pareti trasparenti costituissero la vera anima dell’edificio.

Ma la trasparenza ha invaso non solo le aperture

esterne, ma anche quelle interne verticali: quanti

passaggi sotterranei, quanti mercati e ritrovi scavati nelle viscere dell’edificio (si pensi solo al City

Co-op newyorkese) hanno allargato l’“orizzonte

verticale” permettendo all’abitante di percorrere i

locali avendo ai suoi piedi la visione dall’alto, resa

possibile dalla trasparenza del pavimento. Il che

può diventare persino uno spettacolo artisticoarcheologico in molti casi di ruderi antichi; ad

esempio ad Aosta e a Verona dove un intero

quartiere romano è visibile dall’alto, in uno dei

ristoranti di Piazza delle Erbe, attraverso una parete vitrea.

Quale, allora, può essere la conclusione di un

discorso come questo, quanto mai superficiale se

privo di riferimenti tecnologici, attorno a un problema così arduo come quello della trasparenza?

Credo che il problema non possa essere risolto né

oggi né domani perché è intimamente legato a

quello della spazialità interna ed esterna di ogni

costruzione. L’architettura, insomma, non può

essere né solo interna né solo esterna; e la trasparenza – preziosa conquista della nostra epoca –

non potrà mai globalmente prevalere.

* Gillo Dorfles nasce a Trieste nel 1910. Dopo la laurea in

medicina si dedica alla pittura e, nel 1948, è tra i fondatori del

gruppo MAC insieme a Monnet, Soldati e Munari. In seguito

si dedica alla critica d’arte e agli studi di estetica, pubblicando

numerosi saggi. È collaboratore del Corriere della Sera e di riviste d’arte e di architettura.

O

ne of the sharpest observations ever made

by Siegfried Giedion – the great architectural critic – was about transparency. He

said that the designs of certain primitive peoples

continuously attempted to represent everything

that was hidden underneath the ground, as if this

ground itself were transparent. Furthermore,

what reproduction of the “real” is more true than

the one which represents the things not visible to

the naked eye, but that nevertheless exist?

However, if the savage man of the Paleolithic era

was trying to breach, though only virtually, the

separation that divided him from the world, in

TRASPARENZA TRANSPARENCY

our day and age this division has often fallen

away. In truth, it is the very abolishment of the

obstacle between the internal and external space

of a building that remains one of the great conquests of early rationalism.

The dawn of the Modern Movement – culminating in the masterly works by Mies, Breuer, Kahn

and so forth – has often been characterized by

the discovery of curtain walls. These continuous

walls of glass transformed the ancient trilithic

parallelepiped of yore into a kind of aviary open

to views of passersby and, for the edifice’s inhabitant, to a wide vision of the surrounding world.

Enthusiasm for the house on stilts, for the continuous facade free of terraces, for the transparent

wall, was only supposed to last a few decades. It

was soon understood that man often needs a

“shelter,” a closed, secure cocoon where he can

take refuge, protected from the inquisitive looks

of his neighbor as well as from the forced and

invasive intrusion of the outside world.

And yet the conquest of transparency could not

be wholly abandoned. The possibility of using

new materials – from glass to Plexiglas, from

synthetic resins to various plastic materials, all

endowed with some degree of translucency –

made it possible for architecture to return, willingly and often, to the use of the artifice of transparency. In the ceilings that filter down light from

the open sky, in the walls that light up with a

thousand nocturnal points of light, the presence

of glass and other similar materials has bestowed

on urban edifices a dimension that never existed

before. Furthermore, it is a dimension that weds

itself perfectly to man’s present condition of

belonging to an established community (even if

all too often this community living is anything but

appreciated!). From the transparent cupola of the

new Reichstag in Berlin, to the glass pyramids at

the entrance to the Louvre, to the many recent

technological and ecological constructions in

which nature attempts to infiltrate the manmade constructions or where these constructions

associate themselves directly with the greenness

of nature from the start – everything is characterized by the artifice of transparency. An example

may be the brand new Institute for Forestry and

Nature Research at Wageningen, designed by

Stephan Behnisch. It is a completely translucent

structure that allows greenery to penetrate inside

as if it were a kind of greenhouse. Another

example is the great “tropical greenhouse” converted from the old central train station in

Madrid; or the skyscraper of offices created by

Renzo Piano in Sydney in which the half-walls

isolate the apartments from the urban traffic; or

the offices at 88 Wood Street designed by

Richard Rogers in London; or the state government offices by Bucholz and McEvoy in Dublin…

The walls of many buildings have thinned themselves out, have left bricks behind, have distanced

themselves from the “stilts”. They have permitted

outside space to fuse with internal space and,

very often, a number of gigantic public constructions – decidedly “publicity-oriented” such as the

Tokyo Forum designed by Raphael Vign̆oli in

Tokyo, Japan – have permitted the great transparent walls to constitute the true heart and soul of

the edifice. But not only has transparency invaded the external openings, it has taken over the

internal vertical ones as well.

How many underground passages, how many

markets and gathering spaces have been carved

out of the insides of buildings (one has only to

consider the City Co-op in New York), acting to

enlarge the “vertical horizon?” This allows inhabitants to cross the assorted spaces while maintaining at their feet a top view made possible by the

transparency of the very pavement they are

walking on. This effect is even capable of becoming an artistic-archeological show in the case of

many ancient ruins. An example, in Aosta and

Verona, Italy, is the entire Roman neighborhood

visible from above through a glass wall in one of

the Piazza delle Erbe restaurants.

What, then, is the possible conclusion to an

active, engaging subject like this one, though it

be ultimately superficial without any technological reference point, around a problem as arduous

as that of transparency? I believe that the problem can be resolved neither today nor tomorrow

because it is intimately connected with the problem of internal and external space – a problem

that remains a fundamental part of every construction. In the end, architecture is neither simply internal nor external; and transparency – that

precious achievement of our era – can never prevail on a global scale.

* Gillo Dorfles was born in Trieste, Italy in 1910. After obtaining a degree in medicine, he dedicated himself to painting

and, in 1948, was among the founding members of the MAC

group together with Monnet, Soldati and Munari. Later on,

he devoted himself to art criticism and aesthetic studies,

publishing numerous essays. Currently he contributes to the

Italian newspaper, the Corriere della Sera, as well as many art

and architectural magazines.

29

Kisho Kurokawa,

Hotel Kyocera

a Kagoshima.

Kisho Kurokawa,

Hotel Kyocera

in Kagoshima.

Geometria al naturale

Natural Geometry

Ehime, Museo delle Scienze

Ehime, Museum of Science

Progetto di Kisho Kurokawa Architect & Associates

Project by Kisho Kurokawa Architect & Associates

30

In queste pagine,

il Museo delle Scienze

nella prefettura di Ehime,

Giappone. Il complesso

occupa un’area

di 30.000 mq e sorge

nella periferia di Niihama,

nell’isola di Shikoku.

The Museum of Science

in Ehime Prefecture,

Japan. The complex

covers an overall area

of 30,000 square meters

located on the outskirts

of Niihama, on Shikoku

Island.

O

ggi l’architetto si trova in un momento cruciale del suo operare. L’informatica, soprattutto grazie a Internet, oltre ad aver dato

vita alla new economy, sta anche riplasmando la

professione, trasformando il progettista di edifici in

ideatore e coordinatore di una sorta di architettura

“bidimensionale” fatta di superfici-informazione

che, oltre ad avvolgere spazi e volumi, funge da

medium, superando i limiti dei mass media e

creando così una totale integrazione fra informazione, nel senso più totale del termine, e spazio

abitativo. Questa nuova dimensione del progetto

influisce anche laddove non si è ancora giunti ad

un simile grado di avanguardia ma si stanno evidenziando nuove tendenze progettuali come la

ricerca di una nuova identità della struttura architettonica: è, infatti, in atto la tendenza a realizzare

complessi architettonici con un’immagine forte,

quasi mediatica invece di inseguire la pura astrattezza o unicamente la funzionalità.

In tal senso, Kurokawa ha al suo attivo quasi tutta

la sua opera dove suggestione e comunicazione

sono sempre in primo piano.

Il “fiabesco tecnologico”, unito a un mix di tradi-

zione e innovazione, è il mondo in cui uno fra i più

prestigiosi architetti giapponesi crea i suoi progetti.

Se i solidi elementari sono la materia prima dell’opera di Kurokawa, la trasparenza è la “pelle intelligente” in grado di mutare la fisicità del cemento in

una sorta di sogno della materia. Il Museo delle

Scienze della prefettura di Ehime, in Giappone, con

le sue schegge di specchiante “trasparenza” disseminata su volumi puri attraverso l’impiego di lastre

di titanio, è una delle opere che meglio configurano l’identità progettuale del Maestro, autore del

Teatro dell’Opera di Haskovo, in Bulgaria, della torre a capsule di Nakagin e delle Città Libiche.

Il complesso museale sorge in un’area appena fuori

il centro urbano di Ehime e si configura come una

sorta di piccola città ideale, la cui purezza compositiva suggerisce soluzioni possibili a quel problema

della territorialità da sempre alla base del concept

progettuale di Kurokawa. Una territorialità caratterizzata dalla mutazione di luoghi prima marginali,

poi trasformati in avamposti urbani per nuove

espansioni metropolitane.

Il sito su cui sorge il complesso museale è quello

suggestivo dell’isola di Shikoku, nell’area suburba-

TRASPARENZA TRANSPARENCY

31

na di Niihama, ai margini di un’arteria d’importanti

interscambi stradali, ma ciò che rende attraente il

luogo è senza dubbio la commistione tra natura e

artificialità dell’architettura. Il museo, infatti, giace

ai piedi di incantevoli rilievi montani. Il nuovo insediamento ha dunque modificato il paesaggio dell’isola di Shikoku attraverso una simbiosi alimentata

da interrelazioni architettura-ambiente, grazie a

contrappunti e simmetrie fra la dolcezza delle curve naturali del territorio e le puntute strutture

architettoniche, configurate in una sequenza apparentemente casuale in cui cubi, coni e triangoli

danno forma e funzione a un complesso composto

di un planetario e di alcuni corpi di fabbrica destinati agli uffici amministrativi. Nel gioco di trasparenze accennate e di incastri geometrici, Kurokawa

non ha però dimenticato il dato storico-estetico

della cultura architettonica giapponese, frutto di

una sottile alchimia in cui modernità e tradizione

convivono da sempre. Ciò è riscontrabile soprattutto nella concezione planimetrica, dove appare chiara la struttura del giardino giapponese in cui percorsi e volumi si integrano, creando una sorta di

scrittura tridimensionale, di paesaggio interiore

espresso attraverso le forme dell’architettura come

segno e la natura quale superficie significante. Di

particolare spettacolarità, la facciata principale è

caratterizzata da una combinazione di materiali

come alluminio, vetro e calcestruzzo a vista. Il tutto

mixato e ridistribuito con grande maestria compositiva. Maestria evidente anche nella scelta di contrapporre alla sfericità della copertura del planetario il grande cono trasparente, una sorta di montagna tecnologica ma anche metafora “ascensionale”, fuga dalla terra verso gli astri osservati nel planetario. Ma le suggestioni non si esauriscono in

una composizione architettonica orchestrata su un

ottimo compromesso fra geometria euclidea e

giardino zen, poiché anche i percorsi interni sono

altrettanti manifesti della poetica di Kurokawa.

Come, per esempio, il percorso che unisce la grande hall al planetario: realizzato nel sottosuolo, si

snoda anche attraverso la zona su cui insiste uno

specchio d’acqua artificiale che cinge parzialmente

il grande cono e parte della hall, suggerendo come

l’architettura viva anche d’invisibili relazioni, proprio come un corpo vivo in cui flussi e connessioni

interne tengono in vita l’organismo.

32

T

oday, architecture finds itself at a crucial

juncture in its development. Information

technologies, and notably the Internet,

have already established the new economy and

are remodeling the profession. They are transforming the architect into an inventor and coordinator of a kind of “two-dimensional” architecture

composed of information-platforms, an architecture that not only encases spaces and volumes,

but also functions as a medium, overcoming the

limits of mass media and thereby generating a

complete assimilation of information (in the

broadest sense of the term) and living space. The

influence of this new dimension reaches to areas

where even the avant-garde has not yet been

achieved, but where there is increasing evidence

of new design tendencies (as in the search for a

new identity of architectural structures). There is,

in fact, movement toward the creation of architectural complexes exuding a powerful, almost

media image, instead of a quest for pure abstraction or simple functionality.

It is in this vein that almost all of Kurokawa’s work

is being realized – architectural creations in which

suggestion and communication are always at the

forefront. “Technological enchantment” linked to

a blend of tradition and innovation makes up the

world within which one of the most prestigious

Japanese architects creates his projects. If rudimentary solids are the raw material of Kurokawa’s

work, then transparency is the “intelligent skin”

capable of transforming the physical nature of

concrete into a kind of dream matter. The Ehime

Prefecture’s Museum of Science in Japan, with its

shards of reflecting “transparency” scattered onto

solid masses dotted with sheets of titanium, is

one of the architectural works that best represents the creative identity of this Master, who is

also credited with the Opera Theater in Haskovo

(Bulgaria), the capsule tower in Nakagin and the

Libyan Cities.

The museum complex is located just outside of

Ehime’s urban center and is organized like a kind

of small, ideal city whose composite purity suggests possible solutions to the problems of space

that have always been at the core of Kurokawa’s

design concepts. This territoriality is characterized

by the transformation of places that are initially

considered marginal and subsequently become

urban models destined for future metropolitan

expansion.

The museum complex sits on the fascinating site

of the Island of Shikoku, in the suburban Niihama

area, near an important highway interchange. The

heady mixture of nature with the artificiality of

the architecture makes the site very attractive. In

fact, the museum is located at the foot of a

mountain range.

The new construction therefore has significantly

modified the Shikoku Island landscape through a

symbiosis fed by the inter-relationship between

architecture and the natural environment. It is

based on the counterpoints and symmetries

between the softness of the terrain’s natural

curves and the pointed architectural structures of

a seemingly casual sequence of cubes, cones, and

triangles. These elements provide form and function for the complex, including a planetarium and

several outbuildings housing administrative

offices. In the midst of this play of suggested

transparencies and geometric enclosures,

Kurokawa has not forgotten the historical-esthetic

data of the Japanese architectural culture, composed of a subtle alchemy in which modernity

and tradition have coexisted for ages.

This is most easily recognized in the design and

layout of the solid areas. For example, the structure of the Japanese garden is clearly evident in

the integration of pathways and masses that creates a kind of three-dimensional script – a sort of

interior landscape expressed through architectural

forms that act as signs inscribed on the significant

surface provided by nature. The principal facade,

characterized by a combination of materials

including aluminum, glass, and exposed concrete

is just one particularly spectacular aspect.

Everything is mixed together and redistributed

with great compositional mastery. True mastery is

also evident in the decision to counter-balance the

spherical nature of the planetarium’s covering

with an enormous transparent cone. The cone

recalls a kind of technological mountain but also

serves as a metaphor for “ascension,” the escape

from Earth toward the heavenly bodies observed

within the planetarium.

Symbolism is not easily exhausted in this architectural composition that so brilliantly orchestrates

an excellent compromise between Euclidean

geometries and Zen gardens, given that its internal pathways reflect so well Kurokawa’s particular

architectural poetry. The underground pathway is

a perfect example of this as it connects the great

hall with the planetarium, traversing an area

where an artificial pond partially encircles the

large cone and the hall. It evokes the great degree

to which architecture relies on invisible connections, just as the inner workings of a live body

keep the organism alive and thriving.

Particolare degli esterni

della sala espositiva

e dell’atrio, posto

nel grande cono vetrato.

Nella pagina a fianco,

sezione sull’atrio

e il planetario.

Details of the exterior

of the exhibition room

and the atrium, located

in the large glass cone.

Opposite page.

A section of the atrium

and planetarium.

33

34

Sopra, l’atrio visto

dal bacino artificiale sotto

al quale è stato realizzato

un percorso per

raggiungere il planetario.

A destra, pianta del primo

piano. La distribuzione

asimmetrica dei vari

ambienti è configurata

seguendo la disposizione

degli antichi giardini

di pietre giapponesi.

Nella pagina a fianco,

particolare della cupola

del planetario.

Above. The atrium

as seen from the artificial

basin with a pathway

underneath leading

to the planetarium.

Right. A plan of the first

floor. The asymmetrical

distribution of the various

spaces has been arranged

according to the layout

of the ancient Japanese

rock gardens.

Opposite page. Details of

the planetarium’s cupola.

35

36

37

In queste pagine,

particolari dell’atrio

la cui struttura è stata

realizzata in acciaio

e cemento armato.

Details of the atrium,

whose structure is made

of steel and reinforced

concrete.

38

39

Nuove scenografie urbane

New Urban Set-Design

Londra, British Film Institute London IMAX Cinema

London, British Film Institute London IMAX Cinema

Progetto di Avery Associates Architects

Project by Avery Associates Architects

40

T

rasparente e caleidoscopico quanto basta,

per farsi notare. Metropolitano (soprattutto

per il riferimento ai gasometri) per integrarsi con la capitale della rivoluzione industriale. Al

di là della piacevolezza delle forme e dei materiali, il BFI London IMAX Cinema in realtà è frutto

delle buone e “vecchie” idee del Razionalismo.

La forma circolare dell’edificio e la sua macro-grafica

non nascono, infatti, da folgorazione mediatica,

bensì più semplicemente dall’interno verso l’esterno. Al centro dell’edificio, infatti, pulsa lo

schermo semicircolare IMAX, cui è stata avvolta

intorno l’unica “pelle” possibile per non uscire

dal dettato razionalista che, a quanto pare, premia sempre. Trasparenza però fa rima con tecnologia, e tecnologia è un concetto che di solito si

associa all’idea di futuro. In questo caso il futuro

si percepisce attraverso una disciplina progettuale

che si arricchisce di nuovi orizzonti. Architettura e

comunicazione sono infatti il concept su cui lavorano oggi gli architetti più attenti e sensibili alle

nuove tensioni culturali.

Il potenziale dinamismo insito nelle forme circolari del nuovo BFI London IMAX Cinema è pura

energia in sintonia con l’ambiente metropolitano

contemporaneo, attraversato dalle pulsioni consumistiche di una società che metabolizza non

solo merci, ma anche cultura, in questo caso cultura cinematografica al massimo della qualità

tecnologica grazie al sistema IMAX.

Un film proiettato con questo sofisticato sistema

è in grado di coinvolgere emozionalmente lo

spettatore attraverso effetti realistici spettacolari,

impiegando fotogrammi di grande formato, per

TRASPARENZA TRANSPARENCY

esempio il 70 mm, più uno schermo gigante:

normalmente dieci volte più largo e sette volte

più alto di quello convenzionale.

La resa sonora è in questo caso esaltata dalla

favorevole acustica della forma circolare della

sala di proiezione, dove sono inoltre sistemate sei

colonne stereofoniche in grado di produrre un

ambiente sonoro tridimensionale di grande suggestione.

Ma, se all’interno nel buio della sala si vivono

emozioni legate alle vicende cinematografiche,

l’esterno è altrettanto vitale e comunicativo verso

il suo intorno urbano.

La totale trasparenza della “pelle” in vetro strutturale che avvolge l’edificio è una sorta di “banda larga” mutante, sorprendente e multicolore.

L’intrattenimento, l’organizzazione del tempo

libero, tutto ciò che si fa per piacere sta codificando una speciale architettura destinata al loisir

caricata di segni forti, come appunto il BFI

London IMAX Cinema.

Insomma, la città è sempre più popolata di architetture frutto di complesse ibridazioni di cui è

facile percepire i nuclei generatori.

La città futura sembra dunque trasformarsi in un

grande fondale, ritagliato da sagome simili a

strumenti elettronici fuori scala.

Sta nascendo una nuova grammatica compositiva, gestita da nuove figure di progettisti: un po’

ingegneri, un po’ creatori di scenografie urbane.

Certamente effimere, instabili come non mai, ma

infinitamente più ricche di suggestioni e di emozioni diffuse in una città che non solo sembra

cambiar pelle, ma anche pensiero e anima.

41

42

T

r ansparent and kaleidoscopic enough to

make itself noticeable, yet metropolitan

enough (especially in its reference to gas

meters) to meld into the capital of the Industrial

Revolution. Above and beyond the inherent

appeal of its forms and materials, the BFI London

IMAX Cinema is essentially born of the worthy

and “old” ideas of Rationalism. In fact, the circular form of the building and its macro-graphics

do not stem from the glaring light of media

attention, but rather from the interior.

At the center of the edifice, the semi-circular

screen of the IMAX system pulses with life. It is

wrapped in a unique transparent “skin” that prevents its total departure from the always rewarding rationalist dictates. However, transparency in

this sense is associated with high technology,

and high technology is a concept that is usually

associated with the future. Here, the future is

perceived through a project discipline that is

enriched by new horizons. Architecture blended

with communication is, in fact, the concept that

captures the attention of those architects most

sensitive to the new cultural tensions of today.

The inherent dynamism in the circular form of

the new BFI London IMAX Cinema is pure energy

in harmony with the contemporary metropolitan

environment. It is punctuated by the consumer

impulses of a society that metabolizes not only

merchandise, but also culture. In this case, it

concerns cinematic culture at the very highest

level of technological achievement, thanks to the

IMAX system.

A film projected through this sophisticated system is capable of thoroughly engulfing the spectator emotionally in the movie through spectacularly realistic special effects by utilizing large-format

frames. These frames are usually seventy millimeters wide and are projected onto a giant screen

ten times wider and seven times higher than a

conventional movie screen.

Six stereophonic columns produce an extraordinarily suggestive, three-dimensional audio environment that is exalted further by unbelievable

acoustics created by the circular form of the

space. But if the internal darkness of the movie

theaters is home to emotions connected with the

films and their drama, the edifice’s exterior is

even more vital to and communicative with its

urban surroundings.

The total transparency of the structural glass

“skin” wrapped around the building creates a

kind of mutating, surprising and multicolored circular “broadband.” Entertainment, the organization of leisure time, and everything that human

beings undertake for pleasure is acting to codify

a special kind of architecture – one that reflects a

new brand of leisure activities charged with

strong messages. The BFI London IMAX Cinema

is a perfect example of this modern development.

Basically, the city is increasingly populated by

architecture that is the fruit of complex

hybridizations, by which it is relatively easy to

identify the generating nuclei. The future city

seems to be transforming itself into an enormous

backdrop, outlined by silhouettes resembling

over-sized electronic instruments.

A new compositional grammar is being born,

managed by new design personalities who are to

a certain extent engineers and to a certain extent

creators of urban set-design. This new approach

is undoubtedly ephemeral, as unstable as ever.

But it is also infinitely richer in suggestion and

emotion, spreading through a city that is not

only changing its skin, but also its way of thinking and, therefore, its very soul.

Nelle pagine precedenti,

due vedute del BFI (British

Film Institute) che fa

parte di un complesso

di strutture dedicate alla

cultura dell’immagine.

Nella pagina a fianco,

particolare della vetrata

strutturale.

Qui sotto, sezione

trasversale.

Preceding pages.

Two views of the BFI

(British Film Institute),

part of a complex of

structures dedicated to

the culture of images.

Opposite. Details

of the glass structure.

Below. A cross section.

43

Qui sotto, l’ingresso alla

sala cinematografica

e un particolare del

grande schermo IMAX

semicircolare che

prevede proiezioni

con pellicole di maggior

dimensione e un sonoro

con particolari effetti

realistici.

44

Below. The entrance

to the movie theater

and a detail of the

large semi-circular IMAX

screen that allows

projection of largeformat films and boasts

a sound system with

particularly realistic

effects.

Qui sotto, planimetria

generale, pianta del

piano dell’ingresso

e della sala di proiezione

e una sezione sul sistema

della parete vetrata.

Below. General plan,

a plan of the entrance

level and of the film

projection room, as well

as a section of the glass

wall system.

45

Esperanto architettonico

Architectural Esperanto

Bruxelles, Charlemagne Building ristrutturato

Brussels, renovation of the Charlemagne Building

Progetto di Murphy/Jahn

Project by Murphy/Jahn

L’

46

In questa pagina, veduta

generale dell’edificio.

Nella pagina a fianco,

veduta parziale

dell’edificio ristrutturato

attraverso addizioni

e sottrazioni che

ne hanno radicalmente

rinnovato l’aspetto.

This page. General view

of the building.

Opposite page. A partial

view of the restructured

edifice, achieved

through additions

and subtractions that

have radically renewed

its look.

Unione Europea sta cambiando anche il futuro dell’architettura, che trova in una sorta di

“Esperanto” progettuale una sua nuova

identità, in grado di rappresentare la fusione delle

culture del progetto, un tempo circoscritte in ambiti culturali localistici e ora sempre più orientate a

trasformarsi in un mix che, preservando tutte le

identità locali di maggior pregio, produrrà nuove

direzioni di ricerca. Il futuro è, dunque, rappresentato da un’architettura europea tecnologicamente

avanzata come ad esempio quella statunitense, ma

con un linguaggio comune e riconoscibile.

Città dal cuore antico, Bruxelles, da quando è divenuta una delle città simbolo dell’Unione Europea,

sta cancellando le sue tracce storiche.

Grandi insediamenti politico-amministrativi hanno

sconvolto un equilibrio fatto di integrazione fra

città antica, composta di preesistenze medievali, e

stratificazioni di insediamenti risalenti ad epoche

posteriori.

Nonostante la città appaia scintillante di nuovi edifici, tutti vetro e acciaio, il suo delicato equilibrio

risulta sempre più precario. Fortunatamente, il

compito di ridisegnare l’aspetto architettonico

della città europea per antonomasia è stato affidato ad importanti architetti internazionali, capaci

di realizzare opere con una propria identità. È il

caso della ristrutturazione del Charlemagne

Building, che accoglie la sede della Comunità

Europea.

Il quartiere in cui sorge il rinnovato complesso è

caratterizzato da un fronte principale rivolto verso

un asse viabilistico in continua e rapida trasformazione. Nella parte posteriore dell’edificio permangono ancora alcune tracce di un quartiere residenziale di medie proporzioni, ormai destinato a sparire a causa delle nuove costruzioni comunitarie.

Il tema compositivo del progetto si è incentrato

sulla totale integrazione della nuova struttura con

la città, caratterizzata da insediamenti di diversa

natura sia storica che architettonica. Il vecchio

Charlemagne Building è stato realizzato negli

anni Sessanta, quando il complesso era destinato

ad ospitare i primi organismi politico-amministrativi della Comunità Europea. Il progetto di

Murphy/Jahn è quindi incentrato sull’ampliamento e la rifunzionalizzazione di un edificio esistente. Sostanzialmente si tratta di un’operazione di

re-urbanizzazione compiuta attraverso un calibrato lavoro di aggregazione e sottrazione di parti

rispetto al vecchio edificio, per ricreare nuovi rapporti con una maglia stradale in parte ridisegnata

da molte costruzioni in via di compimento.

L’ampliamento del complesso ha necessariamente

comportato una nuova ridefinizione delle masse

architettoniche rispetto ad un intorno di delicato

equilibrio ambientale.

Si è scelta quindi una soluzione che risultasse di

minimo impatto, come solo le pareti vetrate possono assicurare. Il complesso è rivestito di una

sottile “pelle”, un curtain wall in grado di riflettere l’ambiente circostante e quindi integrarsi con il

contesto. La particolare articolazione della pianta

dell’edificio mostra una spiccata tendenza al dinamismo, sottolineata dalla configurazione a forma

di freccia di un particolare lato del complesso che,

in tal modo, si raccorda alla naturale inclinazione

del terreno circostante. La base dell’edificio, su

cui poggia l’intera struttura, accoglie una serie di

funzioni, tra cui l’ingresso principale dove è sistemato un atrio caratterizzato da pareti interamente vetrate, che fungono da elemento mediatore

fra edificio e spazio urbano circostante.

47

48

T

h e European Union is changing many

things, even the future of architecture, as it

discovers a new identity within a kind of

project-based “Esperanto.” It is an identity capable

of representing a fusion of the project’s various

influences, once inscribed within the local cultural

environment, but now increasingly oriented

toward becoming a mix. This mix is producing new

directions for inquiry and research while at the

same time striving to preserve all the more important local identities. Therefore, the future is headed

toward a European architecture as technologically

advanced as, for example, that of the United

States of America, but possessing a common language that is recognizable to all its citizens.

Brussels is a city with a historic center, but ever

since it became one of the European Union’s symbolic cities, it has been changing its historic countenance. Large political-administrative office buildings have upset the equilibrium between ancient,

historic city sectors composed of medieval structures, and layers of construction built over successive past epochs. Despite the fact that the city

appears to sparkle with new buildings encased in

glass and steel, its delicate balance and harmony

are increasingly endangered due to its modernization process. Fortunately, the work of redesigning

the architectural image of this European city par

excellence has been entrusted to important international architects – men and women capable of

creating architecture with its own identity. This is

exactly what has happened with the renovation of

the Charlemagne Building designed to host the

headquarters of the European Community. The

renovated complex is located in a neighborhood

characterized by a principal front along a roadway

axis that is under continuous yet rapid transformation. Beyond the back section of the edifice there

remain some traces of a medium-sized residential

neighborhood, now destined to disappear because

of the plethora of new European Union construction projects. The theme of the project centers on

a total integration of the new structure into the

surrounding city. It is characterized by edifices

diverse in both history and architectural image. The

original Charlemagne Building was built during the

1960s. The complex was intended to host the first

political-administrative organizations of the

European Community. Therefore, the Murphy/Jahn

project focuses on an expansion and reworking

of a pre-existing building. Essentially, this is a

re-urbanization project carried out through a

carefully orchestrated effort of aggregation. It

includes the removal of certain parts of the original

edifice in order to develop new relationships with

roads that have been partially re-constructed by

numerous projects, many of which are currently

underway. The expansion of the complex has

necessitated a re-definition of the architectural

mass when compared with the delicate environmental equilibrium of its surroundings.

It is with this in mind that the architects chose a

solution that would have a minimum impact, an

impact that only glass walls can provide. The complex has been outfitted with a thin “skin” or curtain wall, a substance capable of reflecting the surrounding environment thereby integrating the

building neatly into its context. The particular articulation of the edifice’s floor plan shows an obvious

tendency toward dynamism. This is emphasized by

the arrow shape of one side of the complex that

responds to the natural inclination of the surrounding terrain. The base of the building, on which the

entire structure rests, hosts a series of functions

including the main entrance. Inside is an atrium

defined by all-glass walls, an addition that functions as a mediating element between the edifice

and the surrounding urban space.

49

Particolare della facciata

vetrata e, nella pagina

a fianco, la scalinata

che porta alla piazza

sopraelevata.

Details of the glass

facade and, opposite

page, the stairway that

leads to the raised plaza.

Particolari della parete

vetrata vista dall’interno

e dettaglio tecnico del

sistema di facciata.

Details of the glass walls

seen from the inside and

technical details of the

facade system.

50

51

Visioni ad assetto variabile

Visions on a Variable Axis

Bilbao, aeroporto di Sondica

Bilbao, the Sondica Airport

Progetto di Santiago Calatrava Valls

Project by Santiago Calatrava Valls

I

52

La facciata interamente

vetrata sul lato nord

lunga circa 36 m.

Il complesso aeroportuale,

che copre un’area

di 38.000 mq sorge

a circa dieci chilometri

dalla capitale basca.

The glass-encased

facade on the north

side stretches nearly

36 meters.

The airport complex,

which extends over

a 38,000 square-meter

area, is located just ten

kilometers from the

Basque capital.

l futuro? Per alcuni è un ritorno all’età dell’oro:

quando l’architettura era un sapere in cui confluivano, in parti uguali, arte e scienza. L’Umanesimo, dunque, almeno in architettura, sta rinascendo

come cultura del futuro?

Anche se Calatrava non è più quel genio noto solo

agli addetti ai lavori, ma una vera star globale, le

sue opere sono ancora sorprendenti, intense, cariche di un pathos in grado di emozionare ma anche

di celare, all’interno di forme e volumi di grande

impatto visivo, raffinatissimi calcoli strutturali.

L’architetto-ingegnere valenciano è attualmente

forse l’unico progettista erede di Gaudì. Al grande

maestro catalano si è, infatti, ispirato per realizzare

l’aeroporto di Sondica. Il riferimento progettuale è

inequivocabilmente il sottoportico inclinato del

Parco Güell, a Barcellona, rielaborato da Calatrava

su una pianta sinusoidale. Realizzato circa dieci

anni fa, l’aeroporto di Sondica è oggi in piena attività e dispone di otto gate. Promosso dalle autorità

di Bilbao per dotare un’area metropolitana in

costante sviluppo di un grande scalo aereo, l’aeroporto dista circa dieci chilometri dalla città basca.

Destinato inizialmente a sostenere un traffico

annuo di due milioni di viaggiatori, lo scalo è ora

predisposto per accogliere anche un flusso di oltre

dieci milioni di passeggeri all’anno.

Il progetto sviluppa l’idea di un terminal compatto,

caratterizzato da grandi superfici vetrate e articolato su quattro piani. La semplificazione distributiva è

uno dei concetti portanti, attuato attraverso un

impianto semplificato, caratterizzato dal contenimento dei percorsi interni destinati a favorire

soprattutto l’unitarietà dello spazio complessivo.

Ciò favorisce gli spostamenti dei passeggeri e il

miglior orientamento possibile dei viaggiatori.

Intorno a questo nucleo funzionale, sorgono due

grandi ali laterali, capaci di accogliere partenze e

arrivi, ma anche tutti gli uffici amministrativi. Un

grande parcheggio, a quattro livelli, assicura un’adeguata connessione fra aeroporto e trasporto

pubblico e privato.

Strutturalmente, l’aeroporto si sviluppa su un sistema di pilastri, travi e archi in cemento armato, in

grado di assicurare stabilità alla grande copertura

metallica nervata, sviluppata su una pianta triango-

TRASPARENZA TRANSPARENCY

lare e conformata su un volume complesso e di

grande impatto visivo. Le ali laterali sono protette

da una doppia copertura voltata, rinforzata da un

sistema di costole e montanti di acciaio posti su

pilastri di calcestruzzo.

La “piegabilità delle strutture nello spazio” è alla

base dell’assunto poetico di Calatrava e fa da perno per un impiego complesso della geometria, ma

anche per la dinamica e la leggerezza, fondamentali nella sperimentazione strutturale dell’opera di

ingegneria. Tuttavia, sperimentazione tecnologica e

soluzioni strutturali innovative non sono mai poste

in primo piano, esibite, ma risultano, invece, organiche alla composizione generale dell’opera architettonica. Il tema della copertura, per esempio,

spiega tale processo attraverso una figura semplice

e complessa nello stesso tempo come la vela, già

impiegata per la copertura delle officine Jakem,

uno dei primi importanti progetti elaborati da

Calatrava all’inizio dell’attività professionale.

Calatrava è tuttora impegnato, anche come teorico, in un dibattito fondativo per l’architettura contemporanea e si batte per risolvere le problemati-

che che coinvolgono la riconoscibilità sociale, ma

anche la stessa identità dell’architettura e dell’ingegneria. Esistono, insomma, ancora alcuni nodi da

sciogliere come quello che ha dato origine ad alcune polemiche interne al mondo dell’architettura e

sostanzialmente alimentate dalle “eresie” di Frank

Gehry (per esempio: il nuovo Museo Guggenheim

di Bilbao), contro cui si batte una sorta di confraternita di architetti e ingegneri puristi, incapaci di

superare la rigida separazione fra architettura e

ingegneria. Problema superabile attraverso un’esperienza progettuale che non escluda la componente artistica nell’opera architettonica ma neanche in quella infrastrutturale come, per esempio,

un grande viadotto.

Anche l’opera di Calatrava ha generato contrasti e

divergenze, soprattutto fra gli addetti ai lavori: era

ritenuta destabilizzante, per l’ordine costituito, la

carica visionaria che caratterizza l’Auditorium di

Tenerife, la Città delle Scienze di Valencia e l’ampliamento del Museo di Milwaukee, interessanti

proprio per le ricerche sulle potenzialità comunicative dell’architettura, intesa come medium.

53

54

Particolare di un gate

d’imbarco.

Details of a departure

gate.

T

he future? For some, it will be a return to

the Golden Age, an epoch in which architecture was a body of living knowledge

com-posed equally of art and science. Could it be

said that Humanism, at least in architecture, is

being reborn as the culture of the future?

Although Calatrava is no longer the type of genius

recognized only in his field, but as a global star, his

work continues to elicit surprise. It is intense, charged with a pathos capable of stirring emotions.

But it is also capable of hiding extremely refined

structural calculations within forms and volumes

that present an extraordinary visual impact.

Currently, this architect/engineer from Valencia is

perhaps the only architectural designer who can be

considered an heir to Gaudì.

In fact, he found inspiration in the work of the

great Catalan master for his Sondica airport

project. The design reference is unquestionably evident in the sloping interior of the portico in

Barcelona’s Güell Park that was re-elaborated by

Calatrava based on a sinusoidal plan.

Created almost ten years ago, the Sondica airport

today is fully operational and outfitted with eight

gates. It was promoted by the authorities in Bilbao

in order to provide a major airport for the constantly expanding metropolis. The Sondica construction is located approximately ten kilometers

from the Basque city. Initially intended to sustain

an air passenger volume of two million travelers

per year, this airport will now be able to accommodate a flow of more than ten million passengers

per year. The project expands on the idea of a

compact terminal, characterized by large glass surfaces articulated over four floors.

A simplified ground plan gives the notion of distributive simplification as one of the main concepts. The layout calls for careful containment of

the internal pathways that are designed primarily

to support the unity and singularity of the comprehensive space. This concept facilitates the flow

of passengers and provides travelers with the best

possible orientation within the space.

Two great wings are spread around this functional

nucleus, each of which is capable of hosting both

arrivals and departures, as well as housing all the

administrative offices. A large parking area extends

over four floors to guarantee adequate connection

between the airport and both public and private

transportation.

Structurally, the airport is built on a system of

reinforced concrete pillars, girders and arches to

provide ample stability for the large ribbed metallic

covering. Its triangular form helps emphasize its

strong visual impact. The lateral wings are protected by a double-vaulted covering that is in turn

reinforced by a system of structural ribs and steel

stanchions running up from concrete pillars.

The “flexibility of structures in space” is basic to

Calatrava’s assumed poetry, and functions as the

pivot for a complex blend of geometry. It is also

central to dynamics and lightness in his work, both

of which are fundamental to the structural experimentation that lies at the heart of engineering.

When all is said and done, technological experimentation and innovative structural solutions are

never on display at the center of attention. Instead,

they are organic to the general composition of an

architectural work. The theme of the covering, for

example, explains this process through a simple yet

complex figure that resembles a large triangular

sail billowed by the wind. He used a similar theme

in the covering of the Jakem warehouse, one of

the first major projects conceived and undertaken

by Calatrava at the very beginning of his professional career. Calatrava is still engaged in work as a

theorist in the fundamental debates of contemporary architecture. He continues to strive to resolve

55

problems and issues that involve not only social

recognition, but the very identity of architecture

and engineering, too. Essentially, there still exist

relevant knots to untangle. For example, the issue

which has created considerable controversy within

the world of architecture and is substantially supported by Frank Gehry’s “heresies” (e.g. the case of

the new Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao). Such

issues are being fought by a sort of fraternity of

architects and purist engineers who seem unable

to conquer the rigid separation between architecture and engineering. It is a problem that can be

overcome by using experience from projects that

integrate the artistic component in both architectural works and infrastructures, such as in a great

viaduct.

Even Calatrava’s creation has generated contrasts

and divergences, especially among those working

within the field of architecture. What was once

considered destabilizing – according to the established order – in the visionary charge that characterizes the Auditorium in Tenerife, the City of Science

in Valencia and the expansion of the Milwaukee

Art Museum, has now been recognized as relevant

and interesting. This is precisely due to the exploration of the communicative potential of architecture, now intended and understood as medium.

In alto, particolare della

grande copertura

a sbalzo e, qui a destra,

dall’alto in basso, piante

del piano terra e del

livello partenze.

Above, detail of the

large cantilevered roof

and right, from top

to bottom, plans

of the ground floor

and departure level.

Parete vetrata del tunnel

sotterraneo destinato

al parcheggio di quattro

piani.

Glass walls of the

underground tunnel

designed for the

four-floor parking garage.

56

57

Veduta generale degli

otto gate e, in basso,

particolare della grande

copertura a sbalzo.

Overall view of the eight

gates and, below, detail

of the large cantilevered

roof.

58

Dettaglio della copertura

e, in basso, la copertura

con il sistema strutturale

di sostegno in acciaio.

Details of the roof and,

below, the roof with its

steel structural support

system.

59

Prospetto e, in basso,

particolare di un

sottopassaggio che

conduce al parcheggio

interrato.

60

Elevation and, below,

detail of an underpass

leading to the

underground parking

garage.

Sezione trasversale

e particolare dell’atrio

realizzato in cemento

a vista.

Cross section

and detail of the atrium,

built with exposed

concrete.

61

62

63

Trasparenze in viaggio

Transparencies On the Road

Houten, stazione di servizio

Houten, Service Station

Progetto di Samyn et Associés

Project by Samyn et Associés

64

N

egli anni Sessanta, Roy Lichtenstein definiva

le pompe di benzina “monumenti commerciali, altari ai beni di consumo”, e prefigurava un futuro sempre più popolato di “mostruosità”

ipertrofiche, iperrealistiche cattedrali dedicate alla

glorificazione delle multinazionali petrolifere. Dopo

quarant’anni, lo studio d’architettura Samyn et

Associés propone invece una netta inversione di

tendenza, puntando su un raffinato understatement linguistico, espresso attraverso materiali inusuali, industriali pur senza insistere nell’high-tech,

poveri eppure “intelligenti”, poiché in grado di

integrarsi in qualsiasi contesto senza perdere la

propria identità. Il rapporto identità/forma è attualmente un nodo oggetto di molte riflessioni, sia in

ambito progettuale che teorico. Nel caso di strutture architettoniche ad alto tasso di comunicazione

come le stazioni di servizio, dove è l’originalità

dell’imprinting figurativo a creare consenso, si

intuisce come il concept progettuale vincente sia

poi in grado di tracciare linee di tendenza per il

futuro. Non bisogna inoltre trascurare che, oltre a

diffondersi nel paesaggio reale, tutto ciò che attiene al mondo dell’auto è anche immerso in un

oceano mediatico sempre più complesso e coinvolgente. Riflessioni e ricerche sul futuro del progetto

e della professione dell’architetto non possono evitare un dato di fatto: lo sviluppo dell’informatica

tende sempre più a favorire un’architettura “spalmata” sull’immaterialità del ciberspazio, e quindi la

forma nella sua accezione compositiva tridimensionale è sempre meno elemento centrale nel pensiero dell’architetto. Il rapporto identità/forma, per

esempio, è ormai oggetto di riflessioni per nuove

direzioni di senso, anche perché la stessa figura

dell’architetto sta perdendo centralità nel progetto:

TRASPARENZA TRANSPARENCY

oggi egli condivide la responsabilità progettuale

con nuove figure creative come il symbol maker, il

grafico e, a volte, anche lo sceneggiatore, il regista

e lo scenografo, figure professionali in grado di trasformare l’architettura in una fabbrica di sogni. Le

nuove stazioni di servizio come quella di Houten,

nei Paesi Bassi, progettata da Samyn et Associés,

sono il risultato di una ricerca condotta dalla

società committente per ridare nuovo smalto a un

sistema ormai obsoleto, incapace di comunicare

nuove strategie aziendali. La stazione di servizio è,

infatti, elemento terminale di grande valore iconico: sia come comunicazione pubblicitaria sia per le

implicazioni socioculturali relative al mondo dei trasporti. La sensibilità verso il tema della salvaguardia

dell’ambiente, nella sua accezione più allargata,

comprendente quindi anche problematiche d’impatto sul territorio, è oggi fondamentale per creare

positive ricadute sull’immagine complessiva dell’azienda. In questo caso, la trasparenza degli schermi

in lamiera stirata è garanzia di massima integrazione con l’intorno sia esso agricolo oppure urbano.

Le sinuose pareti che avvolgono la stazione di servizio di Houten, oltre ad alleggerire l’insieme e a

creare quel senso di interiorità tridimensionale,

sono anche percorso guidato per suggerire

sequenze funzionali legate al rifornimento, al controllo motoristico e alla sosta degli automobilisti. È

dunque la dinamica insita nell’immagine dell’automobile ad avere ispirato forme avvolgenti, fluide, in

grado di suggerire orientamento e modalità d’ingresso al complesso. Il doppio ordine di paraventi

funge inoltre da schermo antivento e la linea continua di neon blu, sistemata nei bordi degli schermi,

segnala, con effetti suggestivi, la presenza della

stazione anche durante le ore notturne.

In queste pagine,

particolari degli schermi

antivento in acciaio

zincato della stazione

di servizio di Houten

(Olanda).

Details of the Houten

(Netherlands) service

station’s windscreens

constructed from

galvanized steel.

65

D

66

Rendering di progetto

e, nella pagina a fianco,

i percorsi suggeriti dalla

disposizione degli

schermi antivento.

A project rendering

and, opposite page,

the pathways reflecting

the same layout of the

windscreens.

uring the 1960s, Roy Lichtenstein defined

gasoline pumps as “commercial monuments, altars to the wealth of consumption.” He envisioned a future increasingly populated by hypertrophic “monstrosities,” hyperrealistic

cathedrals dedicated to glorifying multinational oil

and gas companies.

Forty years later, Samyn et Associés is proposing a

total reversal of this architectural trend. The underlying concept focuses on a refined linguistic understatement expressed through the use of unusual

materials. Although these materials are traditionally reserved for industrial construction applications,

they are versatile enough to be used in many other

types of construction without losing their identity.

The identity-to-form relationship is currently a knot

located at the center of considerable reflection and

evaluation, both in design and in theoretical arenas. In the case of highly communicative architectural structures, like the service station, – where

the originality of figurative imprinting creates consensus – one can understand how the winning

design concept could actually outline fashion

trends of the future.

It is also important to highlight that, in addition to

immuring itself in the real landscape, everything

pertaining to the automobile world is also

immersed in an ocean of increasingly complex

media attention.

Reflection and research on the future of the pro-

ject and on the architectural profession cannot

possibly avoid the simple fact that the development of computer science increasingly tends to

favor an architecture “splayed” into the immateriality of cyberspace. Therefore form, in its threedimensional composite meaning, is decreasingly

central to the average architect’s thinking process.

The identity-to-form relationship, for example, has

by now become the object of reflection on new

meaning directions. This is also due to the fact that

the architect himself is losing centrality in the project. Today, he shares design responsibility with

new creative figures like the symbol maker, the

graphic designer and, occasionally, even the

scriptwriter, the director and the set designer –

professionals capable of transforming architecture

into a factory of dreams. The new service stations,

like the one designed for the town of Houten,

Netherlands, by Samyn et Associés, are the result

of client research to develop a new look for a system that is by now obsolete and incapable of communicating new company strategies.

The service station is, in fact, a terminal element of

great iconic value. It serves as a means of publicity

and also holds socio-cultural implications relative to

the world of transportation.

The increased sensitivity to environmental themes

in their broadest sense, including problems of environmental impact, is fundamental today to creating positive feelings toward the overall image of an

oil company. In this case, the transparent metal

screens surrounding the gas station guarantee

maximum integration into both agricultural and

urban surroundings.

The sinuous walls that encase the Houten service

station lighten the whole and create a sense of

three-dimensional interior space.

They also serve as guided pathways that suggest

functional sequences related to filling the gas tank,

automobile inspections and rest area activities.

Therefore, the very dynamics inherent in the image

of the automobile have inspired this enveloping,

fluid form – a form capable of suggesting orientation and means of entry into the complex. The

double row of screens also functions as a windshield. Finally, the continuous neon blue line running along the edge of the screens signals, with

suggestive effect, the presence of the station even

during nighttime hours.

67

La materia sarà immateriale?

Will Matter Be Immaterial?

Roma, Centro Congressi Italia

Rome, Italia Convention Center

Progetto di Massimiliano Fuksas

Project by Massimiliano Fuksas

68

L

a rivoluzione elettronica è stata una straordinaria occasione di rinnovamento per l’architettura: l’informatica, per esempio, ne ha ampliato il campo d’azione trasformandola in uno straordinario medium globale. In certi casi però l’eccessiva contiguità con le tecnologie elettroniche ha

decretato una sorta d’azzeramento del processo

compositivo, inteso come aggregazione di volumi,

di equilibrio di pieni e vuoti, il tutto messo insieme

secondo uno schema simile a quello destinato alla

realizzazione di una scultura astratta. Ovvero: l’architetto fa un passo indietro come progettista dello

spazio per lasciare campo libero alla bidimensionalità del linguaggio grafico dell’insegna elettronica.

In occasione della VII Mostra Internazionale di

Architettura alla Biennale di Venezia (18 giugno-29

ottobre 2000) gli architetti americani Robert

Venturi e Denise Scott Brown hanno presentato

progetti e realizzazioni all’insegna di un concept

che non lasciava dubbi: “l’architettura intesa come

edificio generico ornato dall’iconografia elettronica”. Insomma, oggi in architettura non vi sono

dogmi progettuali, steccati entro cui operare all’insegna di un’ortodossia ormai fuori tempo, ma una

pluralità di linguaggi che convivono senza creare

interferenze reciproche.

Il Centro Congressi Italia ne è una prova. La struttura sospesa è, infatti, un elemento di forte comunicazione inserito in un impianto modellato su uno

schema definibile razionalista. L’architettura non è

più organizzata solo intorno a modelli di efficienza,

ma verso la ricerca di un’identità forte, inconfondibile. In questo caso, la ricerca di Fuksas si è orientata verso una struttura aerea che sfidasse la forza

gravitazionale creando una massa composta di trasparenze e densità, dissolvendo così la struttura

materiale in una sorta di visione onirica di grande

impatto psicologico. L’architettura ritorna così a

fondersi con l’arte attraverso la rappresentazione

simbolica dell'onirico, presente nel subconscio più

segreto e profondo. Fuksas compie quindi un’operazione inusuale per un architetto, creando prima

un’immagine forte, clamorosa, spettacolare, e trovando poi il modo di renderla anche funzionale

attraverso un’operazione di exploitation cinematografica (ideare prima la locandina e poi realizzare il

film). Il complesso congressuale ideato da Fuksas è

risultato vincitore in un concorso internazionale

diviso in due fasi, con una giuria presieduta da Sir

Norman Foster. Alla competizione hanno parteci-

pato importanti architetti come, tra gli altri, Richard

Rogers e il gruppo francese AREP.

Il complesso congressuale sarà realizzato nel quartiere EUR a Roma, tra i viali Colombo, Asia,

Shakespeare ed Europa, e sarà il più grande

costruito in Italia. Le forme semplici e squadrate

che caratterizzano il nuovo centro congressuale

sono una citazione e una forma di rispetto contestuale, come spiega lo stesso Fuksas: “Rende

omaggio al razionalismo degli anni Trenta che

segna il volto dell’EUR e all’architettura formalmente pulita dell’adiacente Palazzo dei Ricevimenti e

dei Congressi, progettato da Adalberto Libera”.

Il complesso è destinato ad accogliere tre sale,

TRASPARENZA TRANSPARENCY

rispettivamente di 1.500, 4.000 e 8.000 posti; uno

spazio polifunzionale di 15.000 metri quadrati per

il foyer, alcuni caffè e un ristorante.

La struttura sospesa, chiamata anche “nuvola”,

sarà posta al centro della grande hall e accoglierà

un auditorium e sale riunioni. Il resto del centro

congressuale sarà destinato alle funzioni alberghiere, ma avrà spazi flessibili in grado di trasformarsi

in open space o aree destinate a uffici indipendenti. Una volta in funzione, il centro congressuale

potrà accogliere eventi e manifestazioni con una

presenza di circa diecimila visitatori giornalieri. In

realtà, saranno molti di più se si pensa all’appeal

mediatico del centro congressuale romano: televi-

sione, giornali e Internet divoreranno con grande

avidità un’architettura leggera come una nuvola

ma complessa come una microcittà in cui si percepiscono l’alto e il basso, la densità e il vuoto, il

rumore e il silenzio, il caldo e il freddo, la morbidezza e la durezza, la confusione e la chiarezza.

Insomma, non saranno solamente il teflon e l’acciaio, i materiali con cui sarà realizzata la “nuvola”,

a dare visibilità alla struttura, ma anche la sua

immagine veicolata attraverso i media. Il suo territorio di confronto non sarà dunque solo la città

reale, ma anche le pagine dei giornali e gli schermi

dei televisori e dei computer.

Planimetria generale del

complesso congressuale

da realizzare a Roma

su un’area di 15.000 mq.

L’edificio è composto

da un auditorium, varie

sale riunioni, tre sale,

bar e ristorante.

General plan of the

convention complex

to be built in Rome over

a 15,000 square-meter

area. The building includes

an auditorium, various

meeting rooms, three

halls, a bar and a

restaurant.

69

70

Sezioni longitudinale

e trasversale.

Longitudinal and cross

sections.

T

he electronic revolution has had an extraordinary impact on the advancement of

architecture. For example, computer science

has broadened its field of influence, transforming

architecture into a remarkable global medium. In

certain cases, however, excessive contiguity with

electronic technologies has produced a kind of

nulling of the compositional process understood as

an aggregation of volumes, a balance between full

and empty spaces. It is similar to the full and the

empty spaces that are brought together in a sketch

used in the creation of some abstract sculpture.

More precisely, architecture takes a considerable

step backward as the designer of space in order to

give free rein to the two-dimensional nature of the

electronic graphic language.

During the VII International Architectural Show at

the Venice Biennial Exhibition (June 18th to

October 29th, 2000), American architects Robert

Venturi and Denise Scott Brown presented projects

and realizations influenced by a concept that left

no room for doubt in the minds of onlookers,

“architecture understood as generic edifice decorated with electronic iconography.” Essentially, in

architecture today, there no longer exist project

dogmas, boundaries within which one must work

according to an orthodoxy that has by now fallen

out of style. Instead, there is a plurality of languages that co-exist without creating any undue

reciprocal interference.

The Italia Convention Center is solid proof of this

assertion. The suspended structure is, in fact, a

strong element of communication integrated into

a plan based on a clearly rationalistic outline.

Architecture is no longer organized merely around

models of efficiency, but around the search for a

strong and unmistakable identity.

In this case, Fuksas’s search is oriented toward an

aerial structure that challenges the very force of

gravity, creating a mass composed of transparencies and densities. This play of elements dissolves

the material structure into a sort of dreamy vision

that has tremendous psychological impact. Thus,

architecture returns to a blending with art through

the symbolic representation of the world of

dreams that is present in the most secret and

deepest subconscious. Fuksas carries out an unusual operation for an architect. He first creates a

strong, clamorous, spectacular image, and subsequently finds a way to render it functional through

Rendering del

complesso. Il progetto

di Fuksas è risultato

vincitore del concorso

internazionale per il

nuovo Centro Congressi

Italia all’EUR.

A rendering of the

complex. Fuksas’s

project was the winning

entry in an international

competition to select

a design plan for the

new Italia Convention

Center in Rome’s EUR

neighborhood.

71

a display of cinematographic exploitation. It is as if

he were first creating a movie poster, then the

movie. The convention center designed by Fuksas

was the winning result of a two-phase international juried competition under the direction of Sir

Norman Foster. Numerous prominent architects

participated in the competition, including, among

others, Richard Rogers and the French group AREP.

The center complex will be constructed in the EUR

neighborhood of Rome, between Colombo, Asia,

Shakespeare and Europa streets. It will be the

largest construction of its kind ever built in Italy.

The simple and squared forms that characterize

the convention center are a reference as well as an

expression of contextual respect, as Fuksas

explains, “(The complex) pays homage to the rationalism of the 1930s. That way of thinking greatly

influenced the face of the EUR neighborhood and

the formally clean architecture found in the neighboring Palazzo dei Ricevimenti e dei Congressi,

designed by Adalberto Libera.”

The complex will have three large halls with 1,500,

4,000 and 8,000 seats, respectively. It will include a

multifunctional foyer spanning 15,000 square

meters, several cafes and a restaurant. The sus-

pended structure, also referred to as the “cloud,”

will be located at the center of the great hall and

will contain an auditorium and meeting rooms.

The remaining spaces of the convention center are

destined for hotels and independent offices. Once

the center is open and operational, the structure

will be able to host events and shows for public

audiences of about ten thousand people per day.

In reality, if one considers the media appeal of the

Italia Convention Center, there will surely be more

to come. Television, newspapers and the Internet

will devour an architecture as light as a cloud but

as complex as a micro-city. In this type of design,

one can perceive highs and lows, dense spaces

and emptiness, clamor and silence, hot and cold,

softness and hardness, confusion and clarity. In

other words, there will be more than just Teflon

and steel, the materials out of which the “cloud”

will be constructed to give the structure visibility.

Its very image will spread through the various

channels, lines and outlets of the media.

Therefore, its terrain of comparison will not simply

be the surrounding real city, but also newspaper

pages, television screens and computer monitors

around the world.

Rendering del grande

involucro in acciaio

e teflon di 3.500 mq

posto nella sala

convegni. Definita

“nuvola”, la struttura

sospesa è retta da

nervature in acciaio

e sovrasta un elemento

verticale che accoglierà

il ristorante.

72

A rendering of the

enormous, 3,500

square-meter steel and

Teflon shell located

in the convention room.

Defined as a “cloud,”

the suspended structure

is supported by a steel

framework and hangs

over a vertical component

that will eventually house

the restaurant.

73

La presenza dell’assenza

The Presence of Absence

New York, American Bible Society

New York, American Bible Society

Progetto di Fox & Fowle Architects

Project by Fox & Fowle Architects

74

In queste pagine,

il volume vetrato,

dettaglio della vetrata

strutturale e piante

dei piani terra

e secondo.

The glass-encased

volume, a detail of the

structural glass pane,

and plans of the ground

and second floors.

L’

ampliamento di un edificio esistente come

l’in tervento dell’American Bible Society, è

un tema stimolante e affascinante quanto

un viaggio in un organismo concluso, cui però si

deve modificare il codice genetico per svilupparne

nuove ramificazioni di crescita. Facile intuire quindi

come l’operazione ponga alcuni problemi, sostanzialmente esemplificabili in due distinte filosofie

progettuali: una che, ponendo l’accento sul contrasto per evidenziarne le distinte fasi di realizzazione,

dia il giusto risalto alla creatività del progettista, e

un’altra orientata verso una mimesi totale per limitare al massimo disomogeneità stilistiche e problemi di “rigetto”.