Ippologia, Anno 12, n. 4, Dicembre 2001

43

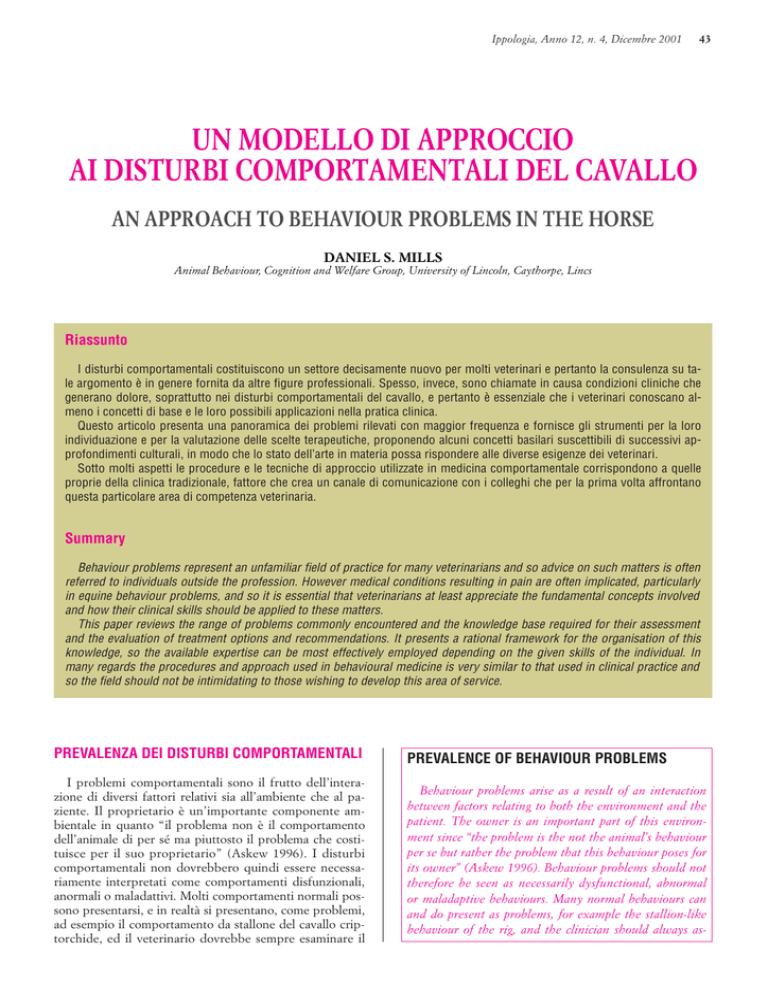

UN MODELLO DI APPROCCIO

AI DISTURBI COMPORTAMENTALI DEL CAVALLO

AN APPROACH TO BEHAVIOUR PROBLEMS IN THE HORSE

DANIEL S. MILLS

Animal Behaviour, Cognition and Welfare Group, University of Lincoln, Caythorpe, Lincs

Riassunto

I disturbi comportamentali costituiscono un settore decisamente nuovo per molti veterinari e pertanto la consulenza su tale argomento è in genere fornita da altre figure professionali. Spesso, invece, sono chiamate in causa condizioni cliniche che

generano dolore, soprattutto nei disturbi comportamentali del cavallo, e pertanto è essenziale che i veterinari conoscano almeno i concetti di base e le loro possibili applicazioni nella pratica clinica.

Questo articolo presenta una panoramica dei problemi rilevati con maggior frequenza e fornisce gli strumenti per la loro

individuazione e per la valutazione delle scelte terapeutiche, proponendo alcuni concetti basilari suscettibili di successivi approfondimenti culturali, in modo che lo stato dell’arte in materia possa rispondere alle diverse esigenze dei veterinari.

Sotto molti aspetti le procedure e le tecniche di approccio utilizzate in medicina comportamentale corrispondono a quelle

proprie della clinica tradizionale, fattore che crea un canale di comunicazione con i colleghi che per la prima volta affrontano

questa particolare area di competenza veterinaria.

Summary

Behaviour problems represent an unfamiliar field of practice for many veterinarians and so advice on such matters is often

referred to individuals outside the profession. However medical conditions resulting in pain are often implicated, particularly

in equine behaviour problems, and so it is essential that veterinarians at least appreciate the fundamental concepts involved

and how their clinical skills should be applied to these matters.

This paper reviews the range of problems commonly encountered and the knowledge base required for their assessment

and the evaluation of treatment options and recommendations. It presents a rational framework for the organisation of this

knowledge, so the available expertise can be most effectively employed depending on the given skills of the individual. In

many regards the procedures and approach used in behavioural medicine is very similar to that used in clinical practice and

so the field should not be intimidating to those wishing to develop this area of service.

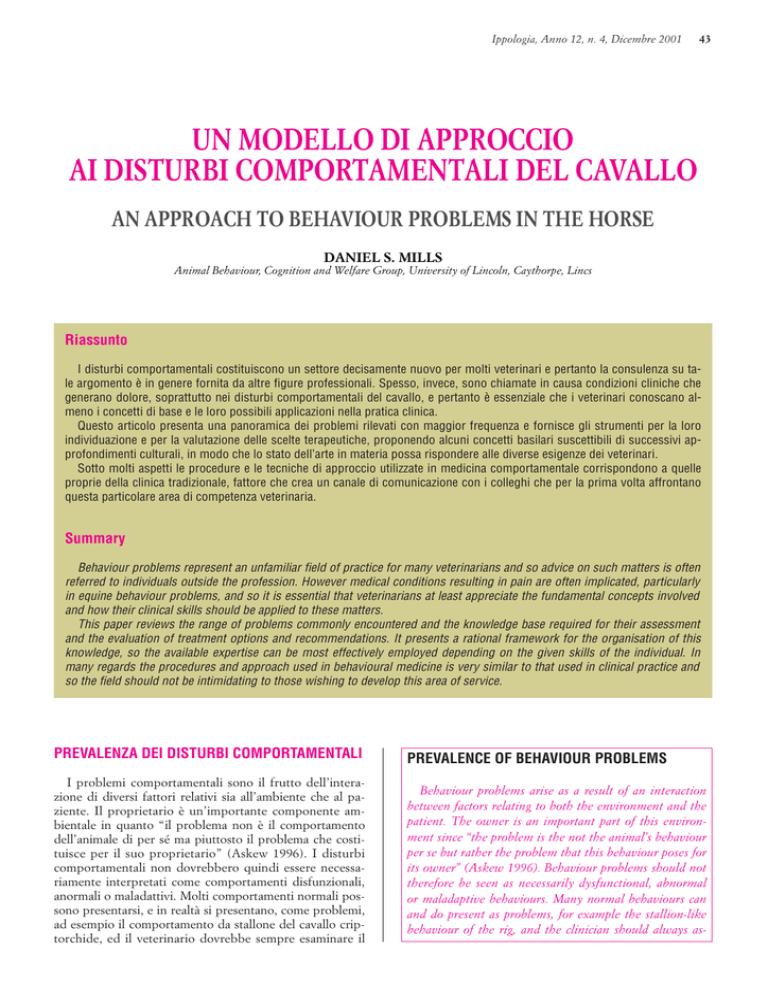

PREVALENZA DEI DISTURBI COMPORTAMENTALI

PREVALENCE OF BEHAVIOUR PROBLEMS

I problemi comportamentali sono il frutto dell’interazione di diversi fattori relativi sia all’ambiente che al paziente. Il proprietario è un’importante componente ambientale in quanto “il problema non è il comportamento

dell’animale di per sé ma piuttosto il problema che costituisce per il suo proprietario” (Askew 1996). I disturbi

comportamentali non dovrebbero quindi essere necessariamente interpretati come comportamenti disfunzionali,

anormali o maladattivi. Molti comportamenti normali possono presentarsi, e in realtà si presentano, come problemi,

ad esempio il comportamento da stallone del cavallo criptorchide, ed il veterinario dovrebbe sempre esaminare il

Behaviour problems arise as a result of an interaction

between factors relating to both the environment and the

patient. The owner is an important part of this environment since “the problem is the not the animal’s behaviour

per se but rather the problem that this behaviour poses for

its owner” (Askew 1996). Behaviour problems should not

therefore be seen as necessarily dysfunctional, abnormal

or maladaptive behaviours. Many normal behaviours can

and do present as problems, for example the stallion-like

behaviour of the rig, and the clinician should always as-

44

Un modello di approccio ai disturbi comportamentali del cavallo

comportamento dell’animale in rapporto al normale comportamento specie specifico (etogramma) del paziente.

Molti altri comportamenti normali, come la risposta a stimoli dolorifici, possono diventare problemi gravi sia come

“vizi sotto sella” che nel cavallo non sellato, sebbene non

siano riconosciuti come tali al loro esordio.

È precipuo dovere del veterinario pratico definire un

ordine di priorità terapeutica, identificare e comprendere

la natura di ogni patologia, obiettivo che può essere raggiunto attraverso l’utilizzo di strumenti diagnostici di routine o supplementari.

Sono stati pubblicati diversi lavori sul rilievo e la distribuzione dei disturbi comportamentali del cavallo. Houpt

(1981) ha riportato che i problemi che le venivano più frequentemente segnalati erano i “vizi” di scuderia (come ad

esempio il ticchio d’appoggio, il ballo dell’orso, il camminare nel box etc., definiti anche stereotipie) e i comportamenti aggressivi. Più recentemente in uno studio sui problemi comportamentali non riferibili a stereotipie Somerville e colleghi (2001) rilevarono che il 29% dei proprietari incontrava difficoltà in passeggiata, il 26% riferiva problemi in scuderia del tipo reticenza da parte del cavallo a

farsi toccare la testa, il 15% riportava problemi sul terreno

di gara, il 14% durante il trasporto degli animali, il 9% riferiva problemi con il maniscalco e il 7% presentava difficoltà quando cercava di condurre l’animale. Non solo questi dati sottolineano quanto frequentemente i problemi

comportamentali insorgano nella popolazione totale, ma

denotano anche una scarsa comprensione della tendenza

naturale del cavallo ad adottare rapidamente strategie

comportamentali di evitamento come risultato dell’esperienza. La conoscenza delle caratteristiche proprie della

specie in oggetto e dei principi delle teorie dell’apprendimento sarebbero perciò d’ausilio non solo nella prevenzione di molti di questi problemi, ma sarebbero essenziali per

trattare adeguatamente i disturbi che sono ormai veri e

propri casi clinici. Si possono ottenere informazioni dettagliate su questi due argomenti specifici in Mills e Nankervis (1999) e Mills (1998). La finalità di quest’articolo è di

proporre un modello razionale per strutturare organicamente le informazioni necessarie per diagnosticare e trattare i disturbi del comportamento del cavallo.

LA NATURA DEI PROBLEMI COMPORTAMENTALI

Se la componente principale di un disturbo comportamentale da riconoscere è il problema che pone al suo proprietario, l’aspetto secondario è che quel comportamento

è costantemente modificato attraverso un circuito di tipo

“feedback”. Così il comportamento che origina il problema oggi non ha più le stesse connotazioni di quello originario; si possono infatti verificare due grandi categorie di

cambiamenti. Innanzitutto, qualsiasi comportamento motivazionale alla base determinerà delle conseguenze sulla

motivazione stessa aumentandola o riducendola nel futuro. Questo processo è definito come condizionamento

operante. Tali conseguenze potrebbero includere la risposta del proprietario che mira al controllo dell’animale ottenendo invece l’effetto opposto. Secondariamente, se il

comportamento è inizialmente elicitato da stimoli specifici, con l’esperienza potrebbero essere preannunciati da al-

sess the behaviour of the animal against the normal

species specific behaviour (ethogram) of the patient. Many

other normal behaviours, like the response to pain may

present as serious problems both under and out of the saddle, although they may not be initially recognised as such.

It is the responsibility of the veterinary surgeon to prioritise treatment, identify and define the nature of any

pathology. This can be achieved using his/her normal diagnostic and ancillary skills.

A number of surveys have been published on the range

of problems encountered. Houpt (1981) reported that the

problems most frequently referred to her were stable “vices”

(such as cribbing, weaving, box-walking etc. also referred to

as stereotypies) and aggression. More recently Somerville

and colleagues (2001) in a survey of non-stereotypic behaviour problems, found that 29% of owners encountered

problems whilst riding out, 26% had problems in the stable such as headshyness, 15% reported problems in the

field, 14% whilst travelling, 9% with the farrier and 7%

when trying to lead the animal. This not only underlies

how frequently problems arise in the general population,

but also reflects a poor understanding in the general population of the horse’s natural tendency to rapidly adopt

avoidance behaviour strategies as a result of experience. A

basic understanding of the nature of the horse and the principles of learning theory would therefore not only help prevent many of these problems but is also essential to treating

those cases that do arise. Information relating to these two

specific subjects may be found in Mills and Nankervis

(1999) and Mills (1998). The aim of this paper is to present

a rational model for the organisation of the information required to assess and treat equine behaviour problems.

THE NATURE OF BEHAVIOUR PROBLEMS

If the first feature of a behaviour problem to recognise is

the problem that it poses for its owner, the second is that behaviour is constantly being modified by feedback. So the behaviour which gives rise to the problem today does not have

the same form as the original behaviour which gave rise to

this. Two broad types of change may occur. Firstly, any motivated behaviour will have motivational consequences which

either encourage or discourage it in future. This is called operant conditioning. These consequences might include the

owners response at control which might be having the opposite to the desired effect. Secondly, if the behaviour is initially triggered by a specific stimulus, with experience these

may be predicted by or associated with other stimuli, leading to generalisation of the response. A process known as

classical conditioning. It is therefore essential to examine

the extent of these changes when trying to establish the nature of the current problem as these affect prognosis. The

prognosis is obviously worse for the owner who has allowed

the problem to change extensively from its original form as

more learning has occurred to develop the behaviour and so

more must be done to reverse this process.

Broadly speaking behaviour problems may be seen to

be derived from four conceptual categories:

1. Normal functional species typical maintenance behaviours. This includes the stallion like behaviour of a rig

Ippologia, Anno 12, n. 4, Dicembre 2001

tri stimoli, o essere associati ad essi, portando ad una generalizzazione della risposta, un processo noto come condizionamento classico. È perciò essenziale quantificare

questi cambiamenti quando si cerca di stabilire la natura

del problema presentato in quanto potrebbero influire sulla prognosi. La prognosi sarà ovviamente meno favorevole

se il proprietario ha permesso che il disturbo si modificasse ampiamente rispetto alla sua forma originale, poiché in

tal caso l’apprendimento è intervenuto pesantemente nello

sviluppo del comportamento, rendendo più arduo il recupero dell’animale.

In generale l’origine dei disturbi del comportamento

può rientrare in quattro categorie concettuali:

1. Comportamenti normali di mantenimento, tipici della

specie. Questo gruppo include il comportamento da

stallone di un cavallo criptorchide e i comportamenti di

richiesta di attenzione in una specie così gregaria come

il cavallo.

2. Risposte normali, tipiche della specie, a qualche forma

di patologia non neurologica. Potrebbe trattarsi di animali che sgroppano per un dolore alla schiena, che si

impennano perché hanno dolorabilità alla bocca o che

mal sopportano di essere maneggiati per uno stato dolorifico presente o pregresso.

3. Comportamenti associati a disfunzioni neurologiche.

Condizioni come la narcolessia e la nevralgia del trigemino che determinano lo scuotimento della testa

noto come headshaking* potrebbero rientrare in questa categoria.

4. Reazioni psicologiche a qualche forma di stress. Ciò include problemi come le stereotipie e le risposte fobiche.

*Il termine “headshaking” (lett. Scuotimento della testa)

indica un comportamento tipico del cavallo, riferibile ad

un movimento di scuotimento della testa improvviso ed

incontrollato [ndt].

Il primo punto fa riferimento ad un bagaglio culturale

che il veterinario pratico già possiede, in quanto gli permette di rilevare uno stato patologico nell’animale. La seconda e la terza categoria rappresentano aree di interesse

clinico; soltanto l’ultima costituisce probabilmente un settore innovativo.

L’ANALISI DEI DISTURBI COMPORTAMENTALI

E GLI APPROCCI TERAPEUTICI

Le cause di un comportamento possono essere lette a livelli diversi, da quello più prossimale a quello più remoto

(Mayr 1961). L’interpretazione più immediata si riferisce

ai meccanismi insiti nell’individuo che determinano l’espressione fenotipica del comportamento, descrivendo i

processi patologici ed eziologici ben noti ai veterinari nello

svolgimento della loro professione. L’interpretazione più

remota spiega il perché tali processi prossimali si devono

verificare, descrivendo la funzione o la capacità adattativa

dei processi stessi. Tinbergen (1963) ha ipotizzato che, in

tale struttura, si deve ricercare un’interpretazione esauriente del comportamento a quattro diversi livelli, distinti

l’uno dall’altro, ma complementari: filogenesi (che considera il comportamento sotto il profilo evoluzionistico),

ontogenesi (le diverse fasi di sviluppo dell’individuo nel

45

and attention seeking behaviours in a species as gregarious as the horse.

2. Normal functional species typical responses to some

form of non-neurological pathology. This might include

bucking due to back pain, rearing due to oral pain or

resentment of handling due to an active or previous

pain focus.

3. Behaviours associated with neurological dysfunction.

Conditions such as narcolepsy and trigeminal neuralgia leading to headshaking might be considered in this

category.

4. Psychological reactions to some form of stress. This includes problems such as stereotypies and phobic responses.

The first of these is obviously part of the normal

knowledge base of the practising clinician since it forms

the basis on which the diseased state can be distinguished

from the undiseased one. The second and third types of

condition represent areas of clinical knowledge; only the

last category perhaps presents a field of completely new

knowledge for the average veterinarian.

ANALYSING BEHAVIOUR PROBLEMS

AND TREATMENT APPROACHES - A FOUR

LEVEL APPROACH

The causes of behaviour may be sought at a proximate or

ultimate level (Mayr 1961). Proximate explanations relate

to mechanisms within the individual which bring about the

physical expression of the behaviour; they describe the

pathological and aetiological processes with which veterinary surgeons are familiar in normal clinical practice. The

ultimate explanations describe why such proximate processes should come about; they explain the function or adaptiveness of the processes. Tinbergen (1963) suggested that, within this framework, a full explanation of behaviour was to be

found at four distinguishable but complementary levels:

phylogeny (which describes the evolutionary history of the

behaviour), ontogeny (the life time developmental history

within an individual), mechanism and adaptive value. Emphasis is commonly given to a single dimension for a given

behaviour as one level is perceived to be central to the nature of the problem but this may also reflect the underlying

philosophy of the therapist and their approach to treatment

(Sheppard and Mills 1998). However a comprehensive approach to the management of problem behaviour should

consider both the behaviour and treatment options at all

four levels. This approach is described below in more detail.

1. Phylogeny

Phylogeny refers to the evolutionary history of the behaviour. It is therefore important to have a grasp of the

principles of evolution and how selective pressures operate. In this way a sound basis is provided for appreciating

what is natural for a horse (which may not be the same as

what is expected) and most importantly what limits to

adaptability might exist. For example, horses have

evolved to feed on forage, and so it is likely that the regulation of nutrient intake is based on “rules of thumb” de-

46

Un modello di approccio ai disturbi comportamentali del cavallo

corso della sua vita), meccanismi di base e valore adattativo. Si tende generalmente a evidenziare una dimensione

unica per ciascun comportamento in quanto si ritiene che

un unico livello sia al centro della natura del problema, ma

questo può anche riflettere la filosofia del terapeuta ed il

suo approccio terapeutico (Sheppard e Mills 1998). In

ogni caso un’analisi bilanciata del disturbo comportamentale dovrebbe considerare il comportamento e le alternative terapeutiche a tutti e quattro i livelli. La parte seguente

propone nel dettaglio proprio questa tecnica di approccio.

1. Filogenesi

La filogenesi considera il comportamento sotto il profilo

evoluzionistico. È quindi importante accennare ai principi

dell’evoluzione e alle modalità di pressione selettiva. In

questo modo si fornisce una base per comprendere tutto

ciò che è assolutamente “naturale” per un cavallo (anche se

può non corrispondere alle nostre aspettative) e, elemento

fondamentale, quali sono i possibili limiti della sua capacità

adattativa. Ad esempio, i cavalli si sono evoluti come erbivori, ed è così probabile che la regolazione dell’assunzione

del nutrimento sia fondata su “regole pratiche” derivanti

dal consumo di una dieta a base di foraggio. Il processo

non si è modificato nel tempo in quanto non si sarebbe ottenuto alcun vantaggio selettivo in senso biologico, anche

se oggi molti cavalli domestici seguono una dieta essenzialmente a base di mangimi, un sistema di alimentazione che

potrebbe richiedere all’organismo animale nuove norme

per un’efficace regolazione dell’assunzione del nutrimento.

Così vi è un potenziale conflitto tra le attuali pratiche gestionali e la tendenza evolutiva (“divario genetico” sensu

McGuire e Troisi 1998). Quando si identificano gli estremi

di questa potenziale conflittualità nell’ambito di un disturbo comportamentale, è probabile che l’animale sia al limite

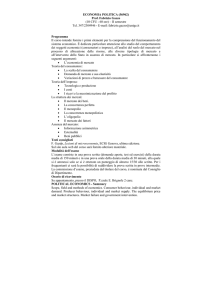

della sua capacità adattativa (Fig. 1).

Il trattamento che è mirato a risolvere la causa di problemi di questo tipo dovrà perciò essere incentrato su

cambiamenti nella gestione dell’animale, poiché la potenzialità per modificare il paziente stesso è probabilmente

molto bassa. In questi casi, se l’intervento terapeutico ha

soltanto la finalità di impedire l’emissione del comportamento, è probabile che risulti essere un ulteriore fattore

stressante legato a frustrazione o ad aumentata difficoltà

d’adattamento (McGreevy e Nicol 1998). Il trattamento

dovrebbe essere diretto a quelle cause prossimali che sono

rilevanti per il benessere del paziente. Questo non implica

necessariamente la scelta di un ambiente totalmente naturale piuttosto che uno al quale l’animale possa effettivamente adattarsi. Se vi è una reale necessità comportamentale, nel senso che l’animale “ha bisogno” di emettere dei

comportamenti legati all’assunzione di foraggio, si può

sfruttare l’impiego di un dispositivo che agisca consentendo un aumento dell’emissione dei comportamenti alimentari, come ad esempio l’EquiballTM, senza aumentare di per

sé la quantità di foraggio (Henderson et al., 1997). Comunque, se il problema è associato ad uno stato di frustrazione prossimale un dispositivo di questo genere potrebbe

esacerbare il disturbo poiché il cavallo potrebbe non essere predisposto ad utilizzare tali modalità nell’assunzione

del cibo dal punto di vista filogenetico.

rived from the consumption of a forage based diet. There

has been no selective advantage in a biological sense for

modification of this process even though many domestic

horses may now be fed a largely concentrate diet whose

efficient regulation might require different rules. There is

thus a potential conflict between current management

practice and evolved tendency (“genome lag” sensu

McGuire and Troisi 1998). When such areas of potential

conflict are identified within a problem, it is likely that

the subject is at the limit of its adaptive capacity (Fig. 1).

Treatment which focuses on the cause of any such problems will therefore need to focus on a change in management as the potential for change in the patient is probably

at its limit. If treatment in these cases aims only at prevention then further stress due to frustration or increased

difficulty in coping is likely to result (McGreevy and Nicol

1998). Treatment should address the proximate causes

which are relevant to the well-being of the patient. This

does not necessitate a totally natural environment rather

an environment to which the animal can effectively adapt.

If there is a genuine behavioural need to forage it may be

that the provision of a toy which encourages such behaviour, such as the “EquiballTM” satisfies such a requirement

without the need for increased forage per se (Henderson

et al., 1997). However if the problem is associated with a

proximate frustration of feeding such a device could exacerbate the problem as the horse may not be phylogenetically adapted to work in such a way for food.

2. Ontogeny

Ontogeny describes the development of the behaviour

within an individual; it is the clinical and ethological history of the case and how learning has modified it. These

are obviously all essential components to the evaluation of

any behaviour. Three phenomena of particular importance

within the ontogenetic process are emphasised here,

namely: sensitive phases in development, behavioural

maturation and learning.

Sensitive phases, like the prenatal, neonatal, transitional and socialisation periods, have traditionally formed the

focus of ethological descriptions of development but are

commonly misunderstood. During these phases the young

horse may be particularly open to making certain associations. Qualitative and quantitative aspects of sensory input at this time have a lasting effect and may lead to later

problems although their effects can usually be reversed albeit with difficulty (Bateson 1979).

Imprinting and attachment onto the maternal figure is

traditionally reported to occur during the neonatal period

which covers the first few hours of the foal’s life (Rossdale

1967). Imprinting onto an inappropriate object, such as a

human can result in both filial and, later on, sexual behaviour being directed towards the imprint object (Bateson

1991). Occasionally, strong attachments to bizarre objects

present at the time of birth may form; for example Tyler

(1972) reports that the attachment of a new-born foal to a

certain tree may occasionally disrupt the mare-foal bond.

Similar problems may arise in the domestic situation, with

attachment to hay mangers and other stable fittings occa-

Ippologia, Anno 12, n. 4, Dicembre 2001

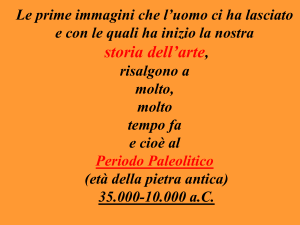

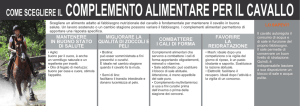

A

Risposte adattative

presenti nel cavallo

ma non necessarie

in cattività

Risposte adattative

che possono essere

utilizzate in cattività

per permettere al cavallo

di adeguarsi

positivamente

all’ambiente

Risposte adattative presenti nei cavalli come

risultato della selezione naturale e di quella

operata dall’uomo, rispettivamente negli ambienti

selvatico e domestico

Nessuna risposta adattativa

presente nel cavallo:

difficoltà o incapacità

dell’animale di adeguarsi

positivamente all’ambiente

B

Risposte adattative necessarie

al cavallo in cattività

FIGURA 1 - Diagramma di Venn che illustra i problemi relativi al “divario genetico” nella popolazione del cavallo domestico (adattato da Fraser et al.,

1997). All’aumentare della sovrapposizione di A su B, si riduce il divario e, di conseguenza, si riduce il rischio di insorgenza di problemi relativi allo stato

di benessere degli animali attribuibili ad un adattamento inadeguato.

A

Adaptations

possessed

but not required

in the captivity

Adaptations which

can be used

in captivity to allow

horse to cope

adequately

Adaptations possessed by horses as a result of

natural selection in the wild and manmade

selection in the domestic environment

No suitable

adaptation possessed

by horse, so difficulty

or inability to cope

B

Adaptations required by the

horse in captivity

FIGURA 1 - Venn diagram illustration of the problems due to the “genome lag” in the domestic horse population (adapted after Fraser et al., 1997). The

greater the overlap between A and B, the small the lag and the lower the risk of welfare problems arising due to inadequate adaptation.

47

48

Un modello di approccio ai disturbi comportamentali del cavallo

2. Ontogenesi

L’ontogenesi descrive le fasi di sviluppo del comportamento nell’individuo; è l’anamnesi clinica ed etologica del

caso e l’esame delle modificazioni operate dall’apprendimento. Si tratta ovviamente di punti essenziali per la valutazione

di qualsiasi comportamento. In questa sede si evidenziano

tre fenomeni di particolare importanza nell’ambito del processo ontogenetico e precisamente le fasi sensibili nello sviluppo, la maturazione comportamentale e l’apprendimento.

Le fasi sensibili, e cioè i periodi prenatale, neonatale, di

transizione e di socializzazione, costituiscono tradizionalmente il fulcro delle descrizioni etologiche dello sviluppo,

ma alcuni concetti sono in genere fraintesi. In queste fasi il

cavallo giovane è particolarmente disponibile nell’operare

certe associazioni. Gli input sensoriali, diversi per quantità

e qualità, che arrivano all’animale in tale momento hanno

un effetto duraturo e possono portare successivamente alla

comparsa di problemi, sebbene gli effetti siano di solito reversibili, anche se con difficoltà (Bateson 1979).

Si riporta generalmente che l’imprinting e l’attaccamento

alla figura materna si attuano durante il periodo neonatale,

identificato con le prime ore di vita del puledro (Rossdale

1967). L’imprinting verso un oggetto inappropriato, come ad

esempio un essere umano, può esitare in comportamenti filiali e, successivamente, in comportamenti sessuali, diretti verso

l’oggetto d’imprinting (Bateson 1991). Occasionalmente si

sviluppa un forte attaccamento verso determinati oggetti presenti al momento della nascita; ad esempio Tyler (1972) riferisce che l’attaccamento di un puledro neonato ad un certo

albero può talvolta spezzare il legame madre-figlio. Problemi

di questo genere possono sorgere nelle condizioni domestiche, in cui si può sporadicamente formare un attaccamento

del puledro a mangiatoie ed altri arredi della scuderia. L’importanza delle esperienze precoci è chiaramente dimostrata

dai lavori scientifici sui problemi che nascono dall’esposizione a stimoli inadeguati durante le prime fasi dello sviluppo

dell’animale. Grzimek (1949) ha dimostrato che i puledri gestiti in isolamento sociale dagli altri cavalli diventavano timorosi nei confronti dei conspecifici quando erano poi introdotti nel gruppo. Williams (1974) ha riportato che puledri nutriti

artificialmente mediante un sistema meccanico di allattamento preferivano la compagnia dell’uomo a quella dei cavalli e

non rispondevano con modalità appropriate ai segnali sociali

dei conspecifici. Non tutti i disturbi comportamentali del puledro, o più specificatamente del puledro privato della madre, sono problemi di imprinting o semplicemente implicano

manifestazioni aberranti di una programmazione genetica,

ma piuttosto riflettono la complessa interazione tra ambiente

e genotipo (epigenesi, Waddington 1961) durante questo

passo cruciale dello sviluppo comportamentale.

La maturazione comportamentale può anche influenzare lo sviluppo dei comportamenti problematici in particolari momenti, vale a dire che lo sviluppo fisico del cavallo

è associato alla comparsa di determinati moduli comportamentali. Ad esempio l’espressione del comportamento sessuale dipende dalla maturazione fisica delle gonadi; quando ciò si attua un puledro facilmente trattabile può diventare più difficile da gestire. Se un problema comportamentale è associato (piuttosto che semplicemente correlato) ad

una particolare fase di sviluppo, è probabile che sia soggetto ad un maggior controllo endogeno. Se un intervento

sionally occurring. The importance of early experience is

clearly demonstrated by the scientific reports of problems

arising from inappropriate exposure during early development. Grzimek (1949) showed that foals reared in social

isolation of other horses became fearful of conspecifics

when they were finally introduced. Williams (1974) reported that foals reared on a mechanical nursing system

preferred human company to that of horses and failed to

respond appropriately to the social signals of conspecifics.

Not all behaviour problems arising in the foal or more especially the orphan foal are problems of imprinting or simply aberrant manifestations of a genetic programme, but

rather reflect the complex interaction of the environment

with the genotype (epigenesis, Waddington 1961) during

this important stage of behaviour development.

Behavioural maturation may also influence the development of problem behaviours at particular times, i.e. the

physical development of the horse is associated with the

emergence of particular behaviour patterns. For example

the expression of sexual behaviour, depends on the physical maturation of the gonads, at this point a previously

tractable colt may become more difficult to handle. If a

behaviour problem is associated (rather than simply correlated) with a particular stage of development, it is likely

to be subject to a greater degree of endogenous control. If

internal intervention e.g. castration or pharmacotherapy is

not possible then the prognosis is inevitably poorer than a

purely learned problem.

Learning may represent the dominant feature of the

problem, as occurs in learned habits but it is also central

to the difference between the current problem behaviour

and its initial expression. This relationship must accordingly be examined in all cases.

Learning in the horse and the problems which can arise

as a result of conditioning or the misapplication of learning theory have been reviewed elsewhere - see Cooper

(1998) for a review of learning in the horse and Mills

(1998) for a review of learned problems. They will not

therefore be reviewed here, but it is worth re-emphasising

how an animal’s experiences with the environment affects

the development and form of a behaviour. Thus the colt,

which was physically punished as it became difficult to

handle when it physically matured, may now show an

avoidance or fear of the handler resulting in secondary

problems like defensive kicking or biting. Even if the association with maturation is recognised, these problems

will persist even following castration as their development

is dependent upon conditioning rather than hormonal factors. In some cases, the initial association is not recognised and the secondary problems are the primary cause of

complaint. Only a full behavioural history will identify

the role of such factors and allow an accurate prognosis

for treatment to be made. A behavioural history must

therefore examine both previous management and experience as well as current status with regards to development

and management, including details of any effects at correction of the problem already taken and their effect.

Treatments which focus on addressing the developmental

aspects of the problem include psychotherapy and retraining.

This involves the controlled manipulation of the environment

to shape future development and recondition the animal.

Ippologia, Anno 12, n. 4, Dicembre 2001

a livello fisiologico come ad esempio la castrazione o un

trattamento farmacologico sono inattuabili, allora la prognosi è inevitabilmente più sfavorevole che nel caso di un

problema che è soltanto frutto dell’apprendimento.

L’apprendimento può costituire la componente principale del problema, come si verifica nei comportamenti appresi mediante abituazione, ma è anche rilevante per la

differenza tra il comportamento problematico osservato e

la sua espressione iniziale. Questa relazione deve perciò

essere analizzata in qualsiasi caso comportamentale.

L’apprendimento nel cavallo e i problemi che possono sorgere come risultato del condizionamento o dell’errata applicazione delle teorie sull’apprendimento sono state esaminate

in altra sede - vedi Cooper (1998) per una rassegna sull’argomento nel cavallo e Mills (1998) per una disamina delle problematiche sull’apprendimento. Perciò tali tematiche non saranno affrontate in quest’ambito, ma è opportuno sottolineare nuovamente come le esperienze ambientali vissute dall’animale influiscano sullo sviluppo e sull’espressione del comportamento. Così il puledro, che veniva punito fisicamente

poiché diventato difficile da gestire dopo la sua maturazione

fisica, può mostrare ora reazioni di evitamento o di paura nei

confronti della persona che se ne occupa, risposte che possono esitare in problemi secondari come calci o morsi di tipo

difensivo. Anche se si ammette la loro associazione con la fase di maturazione, questi disturbi persisteranno anche in seguito alla castrazione poiché il loro sviluppo dipende dal

condizionamento piuttosto che da fattori ormonali. In alcuni

casi l’associazione iniziale non viene riconosciuta e i disturbi

secondari sono in realtà quelli proposti come problema principale. Soltanto un’anamnesi comportamentale approfondita

individuerà il ruolo di questi fattori e permetterà una prognosi accurata e l’impostazione di un piano terapeutico adeguato. Un’anamnesi comportamentale deve perciò considerare sia la gestione dell’animale e le sue esperienze precedenti

sia la situazione del momento in riferimento allo sviluppo e

alle pratiche gestionali, includendo informazioni dettagliate

sui metodi di correzione utilizzati e gli effetti rilevati.

I trattamenti che agiscono sullo sviluppo includono tecniche di psicoterapia e di riabilitazione. Quest’ultima indica un

intervento di controllo sull’ambiente per modellare lo sviluppo futuro dell’animale e ricondizionarlo. Comunque, è importante tenere conto dei limiti di questa tecnica come descritto nel metodo di approccio proposto, che opera a quattro diversi livelli. Un intervento fisiologico, di tipo farmacologico o chirurgico, potrebbe rendersi necessario per facilitare la riabilitazione in riferimento all’attuale stato fisiologico

(vedi oltre). Comunque tali rimedi devono essere considerati

come una misura di sostegno e non un trattamento della

causa del problema quando adottati in questo contesto.

3. Meccanismi di base

Interpretazioni meccanicistiche del comportamento tendono a focalizzarsi sulle basi fisiologiche ed anatomiche

della sua causa immediata. Perciò a questo livello le fasi

sensibili descritte precedentemente rappresentano un periodo di adattamento “neuroplastico” in risposta a determinati input sensoriali, stimoli quantitativamente e qualitativamente diversi, durante le prime fasi di sviluppo (Wolff

1981). Il veterinario, utilizzando la chirurgia e le diverse

49

However, it is equally important to recognise the limits of this

technique as illustrated by this four level approach. Physiological intervention through the use of drugs and surgery may be

necessary to facilitate retraining due to the animal’s current

physiological state (see below). However, such aids must be

recognised as a support measure and not a treatment of the

cause of the problem when used in this context.

3. Mechanism

Mechanistic explanations of behaviour tend to focus on

the physiological and anatomical basis of its immediate

causation. Thus at this level the sensitive phases described

above represent a period of neuroplastic adaptation in response to quantitative and qualitative aspects of sensory

input during early development (Wolff 1981). The veterinary surgeon, through the application of surgery and therapeutics, is in a unique position to understand and treat

the mechanistic aspects of a behaviour problem, but this

does not necessarily mean the cause is being addressed.

When medical and biochemical explanations are offered for a behaviour, they relate to this level of description. This might include the role of allergic rhinitis and

other pathologies in equine headshaking (Cook 1980) or

the importance of serotonin, dopamine and the opiates in

the expression of stereotypic behaviour (Cooper and Dourish 1990). It can be difficult to distinguish between cause

and effect when biochemical models are proposed for psychological conditions. Thus lowered serotonin levels in

the depressed subject may be a reflection of the current

state rather than a cause of it. In the former case treatment with serotonin reuptake inhibitors, like

clomipramine, may relieve the problem by preventing the

formation of the psychological condition but may not actually be addressing the biological cause of the problem.

The use of drugs and surgery to treat behaviour problems focuses on intervention at this level and is a cause

for some controversy. Castration of a rig, undoubtedly addresses the cause of stallion-like behaviour, but myectomy

or combined neurectomy and myectomy (Hakansson et

al., 1992) to control crib-biting supposedly results in an

animal that is no longer physically capable of the behaviour. Whilst this may achieve the aesthetic goal it is likely

to exacerbate the stress of the patient since the cause has

not been addressed (McGreevy and Nicol 1998). However, the use of antidepressants like clomipramine to treat

self-mutilation in stallions (Shuster and Dodman 1998)

may relieve certain aspects of the psychological suffering

associated with the behaviour. Again this emphasises the

importance of a four level approach to the comprehensive

understanding of the problem.

4. Adaptiveness

The adaptiveness of a behaviour relates to its function

and the rules regulating its expression. This is a central

theme of the science of behavioural ecology (Krebs and

Davies 1993). Four categories of behavioural adaptation

may be considered in a clinical context.

50

Un modello di approccio ai disturbi comportamentali del cavallo

forme terapeutiche, è nella posizione ottimale per comprendere e trattare gli aspetti meccanicistici del problema

comportamentale, ma questo non implica necessariamente

che si agisca sulla causa del disturbo.

Le interpretazioni mediche e biochimiche riferite ad un

particolare comportamento si riferiscono a questo livello descrittivo; un esempio nel cavallo può essere il ruolo della rinite allergica e di altre patologie nell’headshaking (Cook

1980) o dell’importanza della serotonina, della dopamina e

degli oppiacei nell’espressione delle stereotipie (Cooper and

Dourish 1990). Può essere arduo distinguere tra causa ed effetto quando si propongono modelli biochimici per condizioni psicologiche. Così la riduzione dei livelli di serotonina

nel soggetto depresso può essere il riflesso dello stato emozionale piuttosto che una sua causa. Nel primo caso il trattamento con gli inibitori selettivi della ricaptazione di serotonina, come la clomipramina, possono alleviare il disturbo impedendo il consolidamento della condizione psicotica, ma

non può in realtà colpire la causa biologica del problema.

L’impiego di farmaci e di tecniche chirurgiche per il trattamento dei disturbi comportamentali sono il fulcro dell’intervento a questo livello, e sono motivo di qualche controversia.

La castrazione di un soggetto criptorchide indubbiamente

colpisce la causa di un comportamento da stallone, ma la

miectomia, o una combinazione di neurectomia e miectomia

(Hakansson et al., 1992) per controllare il ticchio d’appoggio

produce un animale che non è più fisicamente in grado di

emettere il comportamento. Se da un lato un provvedimento

del genere può rispondere ad esigenze estetiche è probabile

che esacerbi lo stress del paziente in quanto non si mira alla

causa (McGreevy and Nicol 1998). Comunque, la somministrazione di antidepressivi come la clomipramina per trattare

fenomeni di auto-mutilazione negli stalloni (Shuster e Dodman 1998) può alleviare certi aspetti della sofferenza psicologica associata al comportamento. Nuovamente questo enfatizza l’importanza di un approccio su quattro livelli per

una chiara comprensione del problema.

4. Valore adattativo

La capacità di adattamento di un comportamento è in

relazione alla sua funzione e ai principi che ne regolano

l’espressione. Questo è un tema di fondo della branca

scientifica dell’ecologia comportamentale (Krebs e Davies

1993). In un contesto clinico si devono considerare quattro diverse categorie di adattamento comportamentale.

Innanzitutto, alcuni comportamenti sono veramente

adattativi perché raggiungono il loro obiettivo, come ad

esempio le minacce aggressive determinano la cessazione

di un’esperienza aversiva. Molti problemi comportamentali hanno un significato adattativo che non è riconosciuto

dal proprietario; ad esempio il cavallo che morde senza

un’evidente giustificazione può aver imparato che le minacce di livello inferiore sono completamente ignorate.

Secondariamente, un comportamento può essere soltanto

parzialmente adeguato come tentativo di adattamento ad una

certa situazione. Il mancato raggiungimento dell’obiettivo

dell’adattamento esiterà in un cambiamento della strategia o

in un’intensificazione del comportamento, nel tentativo di

adattarsi al meglio alle diverse circostanze. Questo genere di

comportamento può palesarsi laddove vi è un divario geneti-

Firstly, some behaviour is truly adaptive because it

achieves its goal, for example aggressive threats result in

the cessation of an aversive experience. Many behaviour

problems have adaptive significance which is not recognised by the owner. For example the horse that bites for

no apparent reason, may have learned that lower level

threats are ignored.

Secondly, a behaviour may be only partially adequate as

an attempt to adapt to a given situation. Failure to

achieve the adaptive goal will result in a change of strategy or intensification of the behaviour in an effort to cope

as best as possible given the circumstances. This sort of

behaviour may be evident in circumstances where there is

a genome lag as described in the phylogeny section above.

For example, Nicol (1999) has suggested that cribbing

may be an attempt by the horse to produce saliva to buffer

against the increased acidity in the stomach caused by the

ration feeding of concentrates. Horses normally produce

saliva only when they are chewing. Therefore when feeding the daily allowance in meals, the total time spent

chewing and thus producing alkaline saliva is reduced

with the result that gastric acidity increases and ulceration

commonly results. Cribbing is not as effective as chewing

on forage for the production of saliva (Houpt, personal

communication), and so the behaviour intensifies. It is an

unsuccessful attempt at adaptation as evidenced by the occurrence of ulcers (Nicol et al., 2001).

Thirdly a behaviour may represent an adaptive but

non-functional response. In this case the animal’s behaviour may be adaptive in a different context but it is ineffective in the current environment. This occurs because

behaviour is controlled by the mechanisms which have

been favoured through natural selection, even though

they may be inappropriate in the current environment.

For example, separation related behaviours which can

cause a problem in the domestic setting have adaptive value in particular settings, such as within a free roaming social group (McGuire and Troisi 1998, Stevens and Price

1997). In this context they help increase the chance of separated individuals being re-united, however in the domestic setting the barriers and control imposed by man make

this response redundant.

Fourthly the behaviour may be truly maladaptive, in

which case a physical pathology and chronic motivational

conflict should be considered and investigated. For example violent headshaking often serves no function but is a

general response to head pain.

In circumstances of motivational conflict or frustration,

the horse may express displacement, ambivalent, redirected or aggressive behaviour. Displacement behaviour is “an

unexpected, seemingly irrelevant movement that occurs

out of the behavioural context to which it is assumed to

belong functionally” (Immelmann and Beer 1989). In

horses, it would seem that the most common form of displacement behaviour relates to grazing. Thus the horse

faced with a conflict between avoiding an apparently aversive situation and approaching it under the instruction of

its rider, may suddenly pull at some nearby grass. This is

often misinterpreted by the rider as a form of stubbornness

and results in punishment of the horse. This is only likely

to exacerbate the problem. Aggressive behaviour in a simi-

Ippologia, Anno 12, n. 4, Dicembre 2001

co come riportato nella sezione sulla filogenesi. Ad esempio

Nicol (1999) ha ipotizzato che il ticchio d’appoggio possa essere un tentativo da parte del cavallo di produrre saliva per

tamponare l’aumentata acidità nello stomaco causata da un’alimentazione a base di mangimi. I cavalli normalmente producono saliva soltanto quando masticano. Perciò quando si

suddivide la razione giornaliera in diversi pasti, il tempo complessivo dedicato alla masticazione, e con esso la produzione

di saliva alcalina, è ridotto con il risultato che l’acidità gastrica

aumenta, causando in genere la formazione di ulcere. Il ticchio d’appoggio non è così efficace come la masticazione del

foraggio per la produzione di saliva (Houpt, comunicazione

personale), e così il comportamento si intensifica. Si tratta di

un tentativo di adattamento infruttuoso come si evince dal

frequente rilievo di ulcere gastriche (Nicol et al., 2001).

Terzo, un comportamento può rappresentare una risposta adattativa ma non funzionale. In questo caso il comportamento dell’animale può essere adattativo in un altro contesto, ma è inefficace nell’ambiente attuale. Ciò si verifica

perché il comportamento è controllato da meccanismi che

sono stati favoriti negli animali mediante la selezione naturale, anche se possono essere inappropriati nell’ambiente in

cui essi vivono. Ad esempio, i comportamenti legati a separazione che possono diventare un problema nel contesto

domestico hanno un valore adattativo in altre situazioni, come in un gruppo sociale che vive in condizioni di libertà

(McGuire e Troisi 1998, Stevens e Price 1997). In tale contesto servono ad accrescere la possibilità che gli individui

che si sono allontanati si riuniscano al gruppo; comunque in

condizioni di vita domestica le barriere e le modalità di controllo imposte dall’uomo amplificano questa risposta.

Quarto, il comportamento può essere realmente maladattativo, nel qual caso una patologia fisica e un conflitto

motivazionale cronico dovrebbero essere analizzati ed investigati. Per esempio un violento scuotimento della testa

spesso non assolve alcuna funzione, ma è una risposta generica ad una dolorabilità alla testa.

In condizioni di conflitto motivazionale o di frustrazione, il cavallo può manifestare un comportamento di dislocazione, ambivalente, ridiretto o aggressivo. Il comportamento di dislocazione è un “movimento inatteso, verosimilmente irrilevante, che si verifica al di fuori del contesto

comportamentale al quale si presume appartenga sotto il

profilo funzionale” (Immelmann e Beer 1989). Nei cavalli

sembrerebbe che la forma più comune di comportamento

di dislocazione sia riferito all’andare al pascolo. Così il cavallo che è messo di fronte alla scelta tra l’evitare una situazione apparentemente aversiva o l’avvicinarsi seguendo le

istruzioni del suo cavaliere può improvvisamente dirigersi

verso l’erba più vicina. Questo fenomeno è spesso frainteso

dal cavaliere che lo interpreta come una forma di ostinazione e reagisce punendo il cavallo, atteggiamento che probabilmente esacerba soltanto il problema. Il comportamento

aggressivo in un contesto simile è spesso parimenti frainteso e determina le stesse conseguenze. Il comportamento ridiretto, che è un normale comportamento diretto ad un

obiettivo diverso dall’originario in quanto viene impedito il

raggiungimento dell’obiettivo primario, e i comportamenti

ambivalenti (comportamenti che includono parti di due

comportamenti antagonisti) possono sottogiacere allo sviluppo di certe stereotipie (McFarland 1966). Ad esempio il

ballo dell’orso può rappresentare una forma di comporta-

51

lar context is often equally misunderstood with the same

consequences. Redirected behaviour (i.e. normal behaviour

directed at an alternative substrate due to frustration towards the primary focus) and ambivalent behaviours (behaviours incorporating parts of two antagonistic behaviours) may underlie the development of certain stereotypical behaviours (McFarland 1966). For example weaving

may represent a form of ambivalent behaviour relating to

locomotory frustration (Mills and Nankervis 1999).

Evaluation of a behaviour at all four levels, not only facilitates an assessment of differential diagnoses, but also

helps reveal the most appropriate course of action. For example, consider a weaving horse. At the phylogenetic level we believe the problem may arise from the inappropriateness of housing a social animal in isolation and addressing this will be central to resolving the cause of the

problem in a given case. Assessing the development of the

problem in an individual will give valuable information

about the extent to which the problem may have generalised and its specific triggers. Some of these may be managed so that they can be avoided as a possible treatment

option. Our current understanding of the mechanistic basis of the behaviour relates to the role of dopamine, serotonin and endogenous opiates in the regulation of behaviour and suggests that most available pharmacological

preparations are only likely to be effective by causing a

general depression of behaviour or compromising welfare

further. Current evidence suggests that the behaviour has

adaptive value through causing a degree of derousal that

helps the animal to cope with the current environment, so

prevention of the behaviour is inappropriate for good welfare. Accepting that social housing is not a viable option,

Mills and Davenport (in press) have evaluated the use of a

mirror in the stable as a substitute with favourable results. Given the four level approach it becomes apparent

that this is a sound practical solution for the problem

which is unlikely to compromise the horse’s well-being

unlike weaving grills or hobbles.

CONCLUSION

The greater an individual’s knowledge in each of these

four fields, the greater their potential to understand the

nature of a behaviour problem and to devise sensitive solutions which respect the welfare of the horse. Whilst

some of the factual information required may be new to

the veterinary surgeon, the paradigm in which it is used is

a familiar to those working in clinical practice; i.e. for any

given case there is a need for a thorough history, assessment of the patient (including clinical examination) and

evaluation of differential diagnoses before recommendations for treatment made. The veterinary surgeon is thus

well placed to deal with behaviour problems as he has

both the essential clinical skills and also much of the essential knowledge base.

Key words

Horse, behaviour, problem, assessment.

52

Un modello di approccio ai disturbi comportamentali del cavallo

mento ambivalente in riferimento a frustrazione espressa a

livello locomotorio (Mills e Nankervis 1999).

L’analisi di un comportamento a tutti e quattro i livelli

non soltanto facilita la valutazione delle diagnosi differenziali, ma fornisce anche indicazioni su come procedere. Si consideri ad esempio un cavallo con il ballo dell’orso. A livello

filogenetico si ritiene che il problema nasca dal fatto di detenere un animale sociale in situazioni di isolamento e un intervento mirato su questo punto sarà il fulcro per risolvere la

causa del disturbo. Valutare lo sviluppo del problema in un

individuo fornirà informazioni preziose sullo stadio di generalizzazione del problema e sugli specifici stimoli elicitanti,

ed alcuni di essi potranno essere utilizzati come possibile

opzione terapeutica nel senso di essere evitati. Le nostre attuali conoscenze sui meccanismi di base del comportamento

si riferiscono al ruolo della dopamina, della serotonina e degli oppiacei endogeni nella regolazione del comportamento,

suggerendo che la maggior parte dei farmaci disponibili sono efficaci determinando una drastica riduzione del comportamento in generale o compromettendo ulteriormente

un già precario stato di benessere. La constatazione pratica

suggerisce che il comportamento ha un valore adattativo

mediante l’abbassamento della soglia di reattività che aiuta

l’animale ad adeguarsi positivamente all’ambiente attuale, di

modo che l’impedire il comportamento è inappropriato se si

desidera garantire uno stato di benessere all’animale. Considerando che la sistemazione del cavallo in “collettività” non

è un’opzione realistica, Mills e Davenport (in stampa) hanno

valutato in sostituzione dell’intervento sociale l’uso di uno

specchio in scuderia ottenendo risultati incoraggianti. Tenendo conto dell’approccio proposto, che si fonda su quattro diversi livelli, è evidente che si tratta di una soluzione

pratica che ha scarse probabilità di compromettere lo stato

di benessere del cavallo a differenza dei vari sistemi che mirano soltanto ad impedire l’emissione del comportamento

come le griglie antidondolamento o le pastoie.

CONCLUSIONI

Approfondendo la conoscenza delle nozioni di base proprie di ciascuna delle quattro branche sopra citate, si potrà

ottenere una miglior comprensione della natura del problema comportamentale e sarà possibile trovare soluzioni realistiche nel rispetto del benessere del cavallo. Sebbene alcune

delle informazioni necessarie possano essere un campo nuovo per il veterinario pratico, il paradigma utilizzato è ben

noto nella clinica tradizionale; per esempio in ciascun caso

clinico è assolutamente indispensabile raccogliere un’anamnesi accurata, esaminare il paziente (includendo l’esame fisico del soggetto) e valutare un diagnostico differenziale prima di procedere con l’impostazione del piano terapeutico.

Si ritiene quindi che il veterinario sia la figura professionale

più adatta per affrontare i disturbi comportamentali, in

quanto depositario non solo delle indispensabili nozioni cliniche ma anche delle necessarie conoscenze teoriche.

Parole chiave

Cavallo, comportamento, disturbo comportamentale,

valutazione.

Bibliografia/References

Askew HR (1996) Treatment of Behavior Problems in Dogs and Cats.

Blackwell Science, Oxford.

Bateson P (1979) How do sensitive periods arise and what are they for?

Anim. Behav. 27, 470-486.

Bateson P (1991) Are there principles of behavioural development? In: Bateson P, Ed.: The development and integration of behaviour. Cambridge

University Press, Cambridge. 19-40.

Cook WR (1980) Headshaking in horses. Part 4: special diagnostic procedures. Vet Med. Eq. Pract. 2, 7-15.

Cooper JJ (1998) Comparative learning theory and its application to the training of horses. Equine vet J. Suppl. 27: 39-43.

Cooper SJ, Dourish CT (1990) Neurobiology of Stereotyped Behaviour, Clarendon Press, Oxford.

Fraser D, Weary DM, Pajor EA, Milligan BN (1997) A scientific conception of

animal welfare that reflects ethical concerns. Anim. Welfare 6, 187-205.

Grzimek B (1949) Ein Fohlen, des kein Pferd kannte. Z. Tierpsychol. 6,

391-405.

Hakansson A, Franzen P, Petersson H, (1992) Comparison of two surgical

techniques for treatment of crib-biting in horses. Equine vet J. 24,

494-496.

Henderson JV, Waran NK, Young RJ, (1997) Behavioural enrichment for

horses: The effect of foraging device (the “Equiball”) on the performance of stereotypic behaviour in stabled horses. In: Mills DS, Heath

SE, Harrington LJ, Eds.: Proc. First Int. Conf. Vet. Behavioural Med.,

UFAW, Potters Bar, 204-208.

Houpt KA (1981) Equine behavior problems in relation to humane management. Int. J. Stud. Anim Prob. 2, 329-337.

Immelmann K, Beer C (1989) A Dictionary of Ethology. Harvard University

Press Cambridge Massachusetts.

Krebs JR, Davies NB (1993) An Introduction to Behavioural Ecology.

Blackwell Science, Oxford.

Mayr E (1961) Cause and effect in biology. Science 134, 1501-1506.

McFarland D, (1966) On the causal and functional significance of displacement activities. Z. tierpsychol. 23, 217-235.

McGreevy PD, Nicol CJ, (1998) Prevention of crib-biting a review. Equine vet

J. Suppl. 27, 35-38.

McGuire M, Troisi A (1998) Darwinian Psychiatry, Oxford University Press,

Oxford.

Mills DS (1998) Applying learning theory to the management of the horse:

the difference between getting it right and getting it wrong. Equine vet

J. Suppl. 27:44-48.

Mills DS, Nankervis KJ, (1999) Equine Behaviour: Principles and Practice.

Blackwell Science, Oxford.

Mills DS, Davenport K (in press) The effect of a neighbouring conspecific

versus the use of a mirror for the control of stereotypic weaving behaviour in the stabled horse. Anim. Sci.

Nicol CJ (1999) Stereotypies and their relation to management. In: Harris

PA, Gomarsall GM, Davidson HPB, Green RE Eds.: Proc. BEVA Specialialist Days on Behaviour and Nutrition. Equine vet J. Ltd, Newmarket, 11-14.

Nicol CJ, Wilson AD, Waters AJ, Harris PA, Davidson HPB (2001) Crib-biting

in foals is associated with gastric ulceration and mucosal inflammation. In: Garner JP, Mench JA, Heekin SP Eds.: Proc 35th Int Conf. Int

Soc. App. Ethol., Centre for Animal Welfare, Davis, CA, 40.

Rossdale PD (1967) Clinical studies on the newborn Thoroughbred foal I:

Perinatal Behaviour. Br. Vet J. 123, 470-483.

Sheppard G, Mills DS (1998) Veterinary clinical ethology: concepts, history,

terminology and future. In: Ibanez, M, Dominguez C Eds.: Etologia Clinica Veterinaria. Proceces Print, Madrid, 23-37.

Shuster L, Dodman N (1998) Basic mechanisms of compulsive and self

–injurious behavior. In: Dodman N.H, Shuster L. Eds.: Psychopharmacolgy of Animal Behavior Disorders. Blackwell Science, Malden, Massachusetts, 185-202.

Somerville K, Goodwin D, Brashaw J, Lowe S, (2001) The prevalence of

behaviour problems in the domestic horse (Equus caballus). In: Proc

2001 CABTSG Study Day, Casey R Ed.

Stevens A, Price J (1997) Evolutionary Psychiatry a New Beginning. Routledge, London.

Tinbergen N (1963) On aims and methods of ethology. Z. tierpsychol. 20,

410-433.

Tyler SJ (1972) The behaviour and social organisation of the New Forest ponies. Anim. Behav. Monogr. 5.

Waddington CH (1961) Genetic assimilation. Advances in Genetics 12, 257-293.

Williams M. (1974) Effect of artificial rearing on social behaviour of foals.

Equine vet J. 6, 17-18.

Wolff JR (1981) Some morphogenetic aspects of the development of the

central nervous system. In: Immelmann K., Barlow G., Petrinovich L.,

Main M., Eds.: Behavioural Development. Cambridge University Press,

Cambridge, 164-190.