Silvia Sarzanini

Rossana Macagno

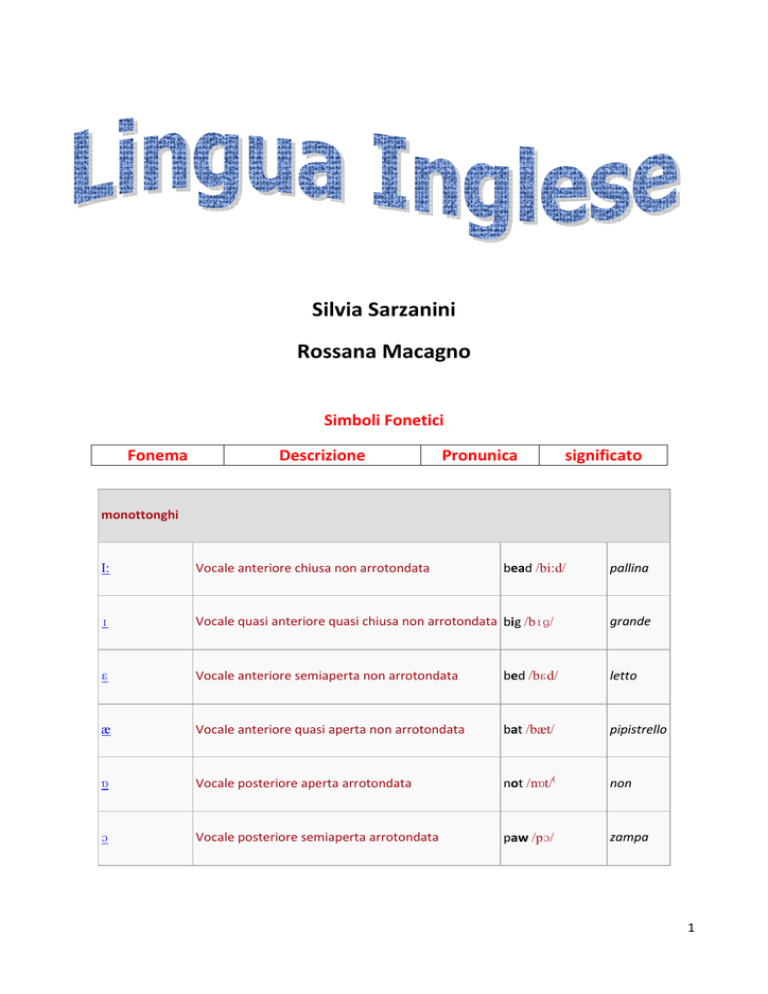

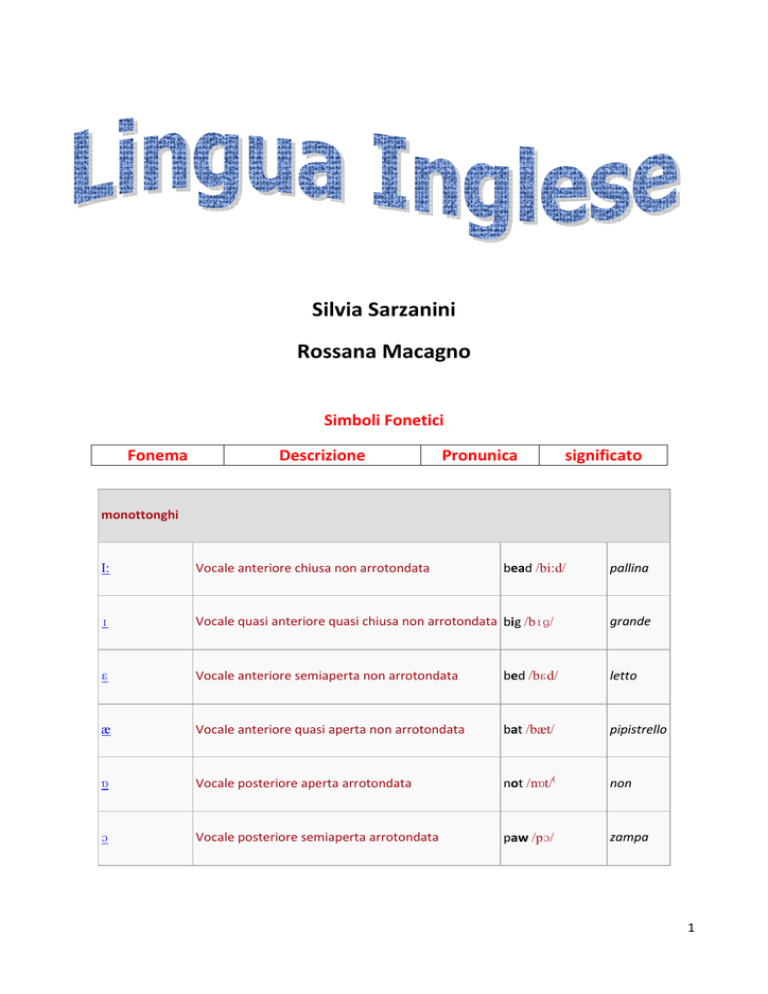

Simboli Fonetici

Fonema

Descrizione

Pronunica

significato

monottonghi

I:

Vocale anteriore chiusa non arrotondata

bead /bi:d/

pallina

ɪ

Vocale quasi anteriore quasi chiusa non arrotondata big /bɪɡ/

grande

ɛ

Vocale anteriore semiaperta non arrotondata

bed /bɛd/

letto

æ

Vocale anteriore quasi aperta non arrotondata

bat /bæt/

pipistrello

ɒ

Vocale posteriore aperta arrotondata

not /nɒt/(

non

ɔ

Vocale posteriore semiaperta arrotondata

paw /pɔ/

zampa

1

ɑ:

Vocale posteriore aperta non arrotondata

father /fa:ðə(r)/ ] padre

ʊ

Vocale quasi posteriore quasi chiusa arrotondata

book /bʊk/

libro

u:

Vocale posteriore chiusa arrotondata

moon /mu:n/

luna

ʌ

Vocale posteriore semiaperta non arrotondata

cup /kʌp/

tazza

ɜ(r)

Vocale centrale semiaperta non arrotondata

bird /bɜrd/

uccello

ə

Schwa

Rosa's /’roʊzəz/ di Rosa

ɨ

Vocale centrale chiusa non arrotondata

roses / ’roʊzɨz/ rose

eɪ

Vocale anteriore semichiusa non arrotondata +

blade /bleɪd/

Vocale quasi anteriore quasi chiusa non arrotondata

lama

oʊ

Vocale posteriore semichiusa arrotondata +

Vocale quasi posteriore quasi chiusa arrotondata

osso

aɪ

Vocale anteriore aperta non arrotondata +

cry /kraɪ/

Vocale quasi anteriore quasi chiusa non arrotondata

piangere

aʊ

Vocale anteriore aperta non arrotondata +

Vocale quasi posteriore quasi chiusa arrotondata

mucca

ɔɪ

Vocale posteriore semiaperta arrotondata +

boy /bɔɪ/

Vocale quasi anteriore quasi chiusa non arrotondata

ragazzo

ʊə(r)

Vocale quasi posteriore quasi chiusa arrotondata +

Schwa

cura

bone /boʊn/

cow /kaʊ/

cure /kjʊə(r)/

2

Vocale anteriore semiaperta non arrotondata +

Schwa

ɛə(r)

fair /fɛə(r)/

giusto

[Riferimento sitografico http://it.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pronuncia_dell'inglese]

Aggettivi numerali

Gli aggettivi numerali si dividono in cardinali (che servono a contare e orinali (che servono a

indicare il posto, l’ordine di un elemento in una serie, a leggere una frazione, ecc.).

Numeri Cardinali

0

Nought/Zero/O

21

Twenty-one

1

One

22

Twenty-two

2

Two

23

Twenty-three

3

Three

24

Twenty-four

4

Four

25

Twenty-five

5

Five

26

Twenty-six

6

Six

27

Twenty-seven

7

Seven

28

Twenty-eight

8

Eight

29

Twenty-nine

9

Nine

30

Thirty

10

Ten

31

Thirty-one

11

Eleven

40

Forty

12

Twelve

50

Fifty

13

Thirteen

60

Sixty

14

Fourteen

70

Seventy

3

15

Fifteen

80

Eighty

16

Sixteen

90

Ninety

17

Seventeen

100

A (one) hundred

18

Eighteen

1,000

A (one) thousand

19

Nineteen

10,000

Ten thousand

20

Twenty

100,000

A (one) hundred

thousand

1,000,000

A (one) million

In inglese si usa la virgola per separare le cifre delle migliaia; si usa invece il punto per

separare le cifre decimali.

Numeri Ordinali

I numeri ordinali si formano aggiungendo il suffisso –th ai relativi numeri cardinali, con

qualche eccezione ortografica: the first, the second, the third, the twenty-first, the twentysecond, the twenty-third, ecc.

1st

The first

21st

The twenty-first

2nd

The second

22nd

The twenty-second

3rd

The third

23rd

The twenty-third

4th

The fourth

24th

The twenty-fourth

5th

The fifth

25th

The twenty-fifth

6th

The sixth

26th

The twenty-sixth

7th

The seventh

27th

The twenty-seventh

8th

The eighth

28th

The twenty-eighth

9th

The ninth

29th

The twenty-ninth

10th

The tenth

30th

The thirtieth

4

11th

The eleventh

40th

12th

The twelfth

50th

13th

The thirteenth

60th

14th

The fourteenth

70th

15th

The fifteenth

80th

16th

The sixteenth

90th

17th

The

seventeenth

100th

18th

1,000th

The eighteenth

19th

1,000,000th

The nineteenth

The fortieth

The fiftieth

The sixtieth

The seventieth

The eightieth

The ninetieth

The hundredth

The thousandth

The millionth

20th

The twentieth

Date

In inglese la data viene formulata utilizzando il numero ordinale e può essere espressa in due

modi:

Es: 7th May, si legge the seventh of May

May 7th, si legge May the seventh

L’anno non è mai preceduto dall’articolo e i suoi numeri vengono letti a coppie.

Es: 1995 si legge nineteen / ninety-five

Attenzione!

1900 si legge nineteen hundred

1905 si legge nineteen hundred and five

L'anno 2000 si legge two thousand, il 2001 two thousand and one e così via.

DAYS OF THE

WEEK

MONTHS (mesi)

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

Sunday

Monday

Tuesday

Wednesday

Thursday

Friday

Saturday

I mesi e i giorni della settimana vanno scritti sempre con la lettera maiuscola.

5

L’ora

Per chiedere l’ora in Inglese si usa l’espressione WHAT TIME IS IT? Oppure WHAT’S THE TIME?

Nella risposta si usa sempre IT seguito dalla TERZA PERSONA SINGOLARE del VERBO ESSERE (e non

dalla terza plurale, come in italiano)

Esempi:

What time is it? It’s nine (sono le nove)

What’s the time? It’s eleven (sono le undici)

All’indicazione dell’ora intera si fa seguire spesso l’espressione O’CLOCK (forma contratta di of the

clock, ossia dell’orologio), che traduce "in punto", "esatte"

Esempi:

It’s five o’clock = sono le cinque (in punto)

It’s ten o’clock = sono le dieci (esatte)

In Inglese le ore si contano DALL’UNA ALLE DODICI. Per distinguere le ore antimeridiane dalle

pomeridiane si usano le sigle A.M. (espressione latina di anti meridiem = prima di mezzogiorno) e

P.M. (post meridiem = dopo mezzogiorno), per indicare le ore da mezzogiorno a mezzanotte.

[Nella lingua parlata tali sigle sono spesso sostituite dalle espressioni

in the morning, in the afternoon e in the evening.]

Fino alla mezz’ora, nell’esprimere l’ora e le frazioni di ora, si usa la parola PAST (passate le…);

dopo la mezz’ora si usa TO (alle…) per indicare i minuti che mancano all’ora seguente

Esempi:

7:20 = it’s twenty past seven 10:50 = it’s ten to ten

Esiste una seconda forma usata per indicare gli orari di treni, aerei ed altri mezzi di comunicazione

che consiste nel leggere i due numeri singolarmente

Esempi:

9:15 = nine fifteen

08:05 = eight five

La parola MINUTES va solitamente omessa, ma ci indica che in Inglese vanno sempre espressi

prima i minuti e poi le ore

Esempi:

6:35 = it’s twenty-five (minutes) to six

5:10 = it’s ten (minutes) past five

HALF traduce mezza e (A) QUARTER traduce un quarto

Esempi.

4:30 = it’s half past four

9:15 = it’s a quarter (o quarter) past nine

6

La parola HOUR (= ora) ha l’h iniziale muta ed preceduta, pertanto, dall’articolo an

N.B.: time = momento, tempo hour = sessanta minuti now = adesso

Preposition of time

Le più comuni preposizioni di tempo inglesi sono le seguenti:

Preposizioni

Uso

AT

Ore, festività o periodi di tempo

IN

Mesi, stagioni, parti del giorno o

date espresse in anni

ON

Giorni della settimana, giorni

specifici o date

DURING

Varie divisioni di tempo

BY

Approssimazione (per difetto)

ABOUT

Approssimazione (per difetto ed

eccesso)

FOR

Continuazione nel tempo

SINCE

Decorrenza

TILL (UNTIL)

Limitazione nel tempo

Esempi:

AT six o’clock, AT Christmas, AT our age

IN June, IN winter, IN the afternoon, IN 1998

ON Friday, ON the first of January

DURING the week, DURING all that time

BY five, BY the end of the week

ABOUT nine, ABOUT the end of the week

FOR a month, FOR a year

SINCE May, SINCE 1988

UNTIL tomorrow, UNTIL 10 o’clock

TILL tomorrow, TILL 4 o’clock

7

Ordine delle parole nella frase

In inglese l’ordine delle parole è più rigido rispetto a quello italiano:

Verbo

Complemento

oggetto

Complementi

mobili / (di luogo

e di tempo)

Complementi

indiretti

Soggetto

Esempio: I bought a computer for my children in Leeds last year.

I complementi mobili, che si riferiscono a tutta la frase, sono facoltativi. Sono detti mobili perché

possono essere spostati all’inizio della frase, lo spostamento è evidenziato da una virgola (Last

year, I bought a computer for my children in Leeds).

Gli articoli

Indeterminativi: a, an (= un,uno, una)

•

“A” “an” precedono i nomi numerabili al singolare:

-

a [ ] davanti a una consonante

a house – una casa, a hat – un cappello

-

an [ ] davanti a un suono vocalico

an eye – un occhio

La scelta si opera in base al suono (vocalico o consonantico) e non a seconda dell’ortografia.

•

Si riferiscono a un solo elemento, oppure a qualcosa di non specificato.

(I’ve got a brother and a sister -Io ho un fratello e una sorella-).

8

•

Non sono accentati

•

Nelle descrizioni o definizioni generali si può usare a/an, oppure il plurale senza articolo.

The rose is my favourite flower –La rosa è il mio fiore preferito

oppure al plurale Roses are my favourite flowers –Le rose sono i miei fiori preferiti

•

Si usano davanti ai nomi che indicano la professione o il carattere di qualcuno.

Peter is a fool! - Peter è uno sciocco

Mary is an engineer. - Maria è un ingegnere.

Nomi senza articolo

(articolo ‘zero’)

Di solito, i gruppi nominali (cioè un nome con eventuali aggettivi / attributi) che indicano

categorie generali non sono preceduti dall’articolo the.

• Nomi plurali:

Dogs are not allowed in this shop. I cani non possono entrare in questo negozio.

I like wild flowers. Mi piacciono i fiori selvatici.

Doctors are paid more than teachers.

Confronta: The dogs next door bark all night. I cani del vicino abbaiano tutta la notte.

• Non numerabili

Milk is good for you. Il latte fa bene.

Salt is used to flavour food.

I like still mineral water. Mi piace l’acqua minerale.

Confronta: The milk on the top shelf is fat-free. Il latte sul ripiano in alto è senza grassi.

Questo gruppo comprende:

Idee astratte: War is a terrible thing.

Alimenti: I love chocolate. I don’t like orange juice.

Lingue: Spanish is spoken by about 300 million people.

Materiali: This chair is made of plastic and leather.

Verbi sostantivati: Learning a foreign language is not a child’s play.

Altri casi in cui si usa l’articolo ‘zero’:

• Luoghi o edifici per i quali s’intende la funzione che svolgono:

Jim is in prison. Jim è in prigione.

Confronta: My company is repairing the prison. La mia ditta sta riparando la prigione.

Casi più frequenti:

Con be in / go to

hospital, prison, bed, class, court, school, church, university, sea

9

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Nazioni, stati e città. Maria comes from Spain. Great Britain is a big island

Vie, strade e piazze. I bought this dress in Bond Street.

Nomi di edifici preceduti dal nome del luogo. We visited Blenheim Palace and

Coventry Cathedral.

Nomi di luoghi come quelli intitolati ad una persona particolare (come quelli di

aereoporti o di università, ecc.) Kennedy Airport, Victoria Station, Hyde Park.

I nomi propri di persona, anche se preceduti da titoli. Carol… Mr Parker Lady

Bracknell

I nomi dei pasti in generale. Dinner is 7.30 (ma The dinner they serve is fantastic)

Nomi geografici (continenti, stati, città, isole, regioni, laghi, canali, monti e isole).

We visited Lake Victoria. It’s in East Africa. Helen spent her holiday in Crete.

Riferimenti storici e generici. I’d like to have lived in Prehistoric Europe / Ancient

Europe.

Mezzi di trasporto in generale. We went there by car/ by train / by plane (ma: we

went there in a really old car)

L’articolo determinativo the

L’articolo the ( = il, lo, la, i, gli, le) precede i gruppi nominali che indicano qualcosa di specifico,

determinato o già descritto. (Un gruppo nominale è formato da un nome con gli eventuali

aggettivi o attributi).

The dogs next door bark all night. I cani del vicino abbaiano tutta la notte.

(Ma diciamo: Dogs are not allowed in this shop. I cani non possono entrare in questo negozio).

I gruppi nominali determinati possono essere di vati tipi. Eccone alcuni:

• Si usa spesso the quando si riferisce a qualcosa di cui si è parlato in precedenza.

We saw a good film last night. It was the new film by Benigni. Abbiamo visto un bel film ieri sera.

Era il nuovo film di Benigni.

• Un nome può essere determinato usando of.

The film was about the love of a girl for her father. L’argomento del film era l’amore di una

bambina per suo padre. (Ma diciamo: Love is a wonderful thing)

• Altre determinazioni:

The war between the two countries lasted for six months. La guerra fra le due nazioni durò sei

mesi. (Ma diciamo riferendoci alla “guerra” in generale: War is a terribile thing).

• Riferimento ad un elemento unico o a qualcosa che è noto all’interlocutore.

Elemento unico: How many astronauts have landed on the moon? Quanti astronauti sono atterrati

sulla luna? (La luna è un elemento unico).

Elemento noto: Where’s the newspaper? Dov’è il giornale?

• Gruppi (comprese le nazionalità nel loro insieme).

The Beatles were a famous pop group. I Beatles erano un famoso gruppo pop.

I really admires the Italians. Ammiro veramente gli italiani.

The Spanish love dancing. Gli spagnoli amino ballare.

• Gli aggettivi sostantivati.

Per indicare una categoria di persone si può usare the + l’aggettivo:

10

The elderly, the sick, the unemployed, the poor need our special care. Gli anziani, i malati, i

disoccupati i poveri hanno bisogno della nostra speciale attenzione.

• Si usa normalmente l’articolo the prima dei nomi dei seguenti luoghi:

Hotels (the Hilton Hotel, the Station Hotel)

Ristoranti o pubs (the Bombay Restaurant, the Red Lion Restaurant)

Teatri (the Palace Theatre, the National Theatre, the Broadway Theatre)

Cinema (the Odeon, the Reposi, the Classic)

Muesi e gallerie d’arte (the British Museum, the Tate Gallery)

Lingue, quando si utilizza la parola language (the English Language, the Spanish language)

Frasi fatte (the sooner, the better)

Superlativi relativi (this is the biggest one. Questo è il più grande)

Catene montuose (The Alps, the Pennines)

Mari e oceani (the Mediterranean, the Pacific, the Atlantic)

Fiumi (the Amazon, the Danube, the Po)

Nomi di navi (We sailed the Neptune. Viaggiammo sul Neptune)

Certe espressioni di tempo (In the past, in the future)

Suonare strumenti musicali (Do you play the guitar?)

Si usa l’articolo the anche per i nomi di luoghi o di edifici con of:

The Bank of England, The House of Parliament, the Tower of London, the Great Wall of China, the

Museum of Modern Art.

Infine si usa l’articolo the anche per i nomi dei giornali:

the Times, the Washington Post, the Evening Standard

Il genere

In inglese le distinzioni di genere appaiono solo a livello di:

-

-

Pronomi personali, possessivi, riflessivi

Maschile: he, him, his, himself

Femminile: she, her, hers, herself

Neutro: it, its, itself.

Pronomi relativi: who e whom per i sostantivi indicanti entità animate e which per i

sostantivi indicanti entità non animate.

I pronomi personali seguono la realtà biologica: è maschile tutto ciò che è maschi, femminile tutto

ciò che è femmina, neutro tutto ciò che non è né maschio né femmina.

Nei sostantivi, il genere si esprime:

11

o Aggiungendo un suffisso al nome maschile:

god/goddess (dio/dea); heir/heiress (erede/erede)

o Più raramente, raggiungendo un suffisso al nome femminile:

widow/widower (vedova/vedovo)

o Usando due parole diverse:

Umano

Non umano

Maschile

Femminile

Maschile

Femminile

King

Queen

Horse

Mare

Father

Mother

Bull

Cow

Uncle

Aunt

Dog

Bitch

Broche

Sister

Buck

Doe

Man

Woman

Cock

Hen

Girl

Gander

Goose

Boy

Female

Fox

Vixen

Male

Ecc.

Ecc.

Ecc.

Ecc.

o Mediante un indicatore di genere preso a prestito dalla precedenti liste:

- A boyfriend / a girlfriend ( un fidanzato/una fidanzata);

A male student/a female student (uno student/una studentessa);

A doctor/a lady doctor or a woman doctor (un dottere/una dottoressa) ecc.

- A he-goat/a she-goat (un capro/una capra);

A buck rabbit/a doe rabbit (un coniglio/una coniglia);

A bull-elephant/a cow-elephant (un elefante/un’elefantessa) ecc.

o La distinzione maschile/femminile può essere neutralizzata:

the chairman (il presidente); the chairwoman 8la presidentessa) the chairperson (la

persona che presiede).

o Molti nomi hanno un’unica forma per il maschile e il femminile; in questo caso, solo il

contesto permette di togliere ogni ambiguità:

parent (padre o madre), cook (cuoco/cuoca), cousin (cugino/cugina), relative (parente),

ecc.

12

Il plurale dei nomi

Il plurale dei nomi numerabili si forma:

o Aggiungendo una –s :

si pronuncia [s] dopo le consonanti sorde p, t, k, f

si pronuncia [z] dopo le vocali, i dittonghi e le consonanti sonore b, d, g, l, m, n, v

Casi particolari:

REGOLA

I sostantivi che terminano per:

-s, -ss, -ch, -sh, -x, o

aggiungono es

si pronuncia [IZ]

SINGOLARE

bus

match

box

potato

I sostantivi che terminano per -o

video

preceduta da vocale, le parole

abbreviate che terminano per -o e le photo

parole straniere che terminano per o, aggiungono normalmente -s:

PLURALE

buses

marche

boxes

potatoes

videos

photos (abbreviazione di

photograph)

pianos

piano

I sostantivi che terminano per -y

baby

preceduta da consonante cambiano theory

la y in i ed aggiungono -es.:

lady

Babies

teories

ladies

Alcuni sostantivi che terminano per: calf (vitello)

-f e -fe fanno il plurale in -ves

leaf (foglia)

half (metà)

knife (coltello)

life (vita)

loaf (pagnotta)

self (sé)

shelf (scaffale)

thief (ladro)

wife (moglie)

wolf (lupo)

calves

leaves

halves

knives

lives

loaves

selves

shelves

thieves

wives

wolves

Plurali irregolari:

man (uomo)

woman (donna)

child (bambino)

men

women

children

13

Alcuni sostantivi che sono stati presi

direttamente dal greco o dal latino,

seguono le regole latine e greche

per la formazione del plurale:

mouse (topo)

ox (bue)

fish (pesce)

sheep (pecora)

deer (cervo)

foot (piede)

tooth (dente)

goose (anatra)

person (persona)

mice

oxen

fish

sheep

deer

feet

teeth

geese

people

crisis (crisi)

oasis (oasi)

phenomenon (fenomeno)

datum (dato)

crises

oases

phenomena

data

Anche le sigle* possono essere

messe al plurale:

Anche i cognomi possono essere

messi al plurale:

VIP

VIPs

UFO

UFOs

Mrs Anderson

The Andersons (gli Anderson,

la famiglia Anderson)

Modificazioni ortografiche

-

-

Aggiunta di una e dopo s, ch, sh, x, z:

Plurale dei nomi (dress dresses)

Terza persona singolare del presente ( wash washes)

Generalmente la finale in –es è pronunciata [IZ] quando segue i suoni [s], [ ], [Z], [ ]

(house houses, rose roses)

Aggiunta di una e dopo una o:

Plurale dei nomi

Terza persona singolare del presente ( do does, go goes)

Consonante + y consonante + ie:

Plurale dei nomi (baby babies, country countries)

Formazione dei nomi (carry carrier)

Formazione degli aggettivi ordinali delle decine (twenty twentieeh)

Terza persona singolare presente ( carry he carries)

Formazione del past e del participio passato (carrycarried, worryworried)

Formazione del comparativo e del superlativo (lazy lazier, happyhappier)

La lettera y può anche trasformarsi in i in certi vocaboli derivati: (marry –aggettivomerrily –avverbio-)

La regola precedente non vale se la y finale è preceduta da una vocale:

vocale + y vocale + y+

S

ed

er

est

14

La lettera y in posizione finale non diventa mai –ie in una forma in –ing; ma –ie può

diventare y. Confrontare: die dying, try tryng

-

-

-

Raddoppio della consonante

Ultima sillaba accentata + vocale breve doppia consonante dei derivati

(sun sunny, hop hopped)

Ultima sillaba non accentata + vocale lunga non si raddoppia la consonante nei deirivati

(sleep sleeping, cheat cheater)

eccezioni:

word

G.B

U.S.A.

Travel

travelled, traveller

traveled, traveler

Worship

worshipped, worshipper

worshiped, worshiper

Quarrel

quarrelled

quarreled

equal

equalled

equaled

Casi particolari

Una e muta scompare davanti a una desinenza: nineninth, grease greasy, write

writer, have having

Quando una e finale appartiene a una sillaba accentata, generalmente rimane davanti

davanti a –ing: be being, see seeing, agree agreeing (eccetto i verbi in ue).

Uso britannico, uso americano

G.B.

-tre: centre, theatre -our: colour, favour U.S.A.

-ter: center, theater

-or: color, favor

15

Gli aggettivi e gli avverbi

In inglese gli aggettivi sono invariabili in genere e in numero (hot – caldo, calda, caldi, calde). Si

usano insieme ai nomi (funzione attributiva) o da soli dopo i verbi come be, look, feel, become

(funzione predicativa).

attributo: It was a lovely day

predicato: The day was lovely

Funzione attributiva

Gli aggettivi si pongono prima del nome; se si usa più di un aggettivo è necessario seguire un

determinato ordine. Non è consigliabile usare più di tre attributi allo stesso tempo. La posizione

degli attributi si può riassumere come segue:

Posizione 1 uno o più aggettivi di questi tipi: a) aggettivi di opinione, b) dimensione, c) età, d)

forma, e) temperatura

Posizione 2 colore: green, blue, ecc.

Posizione 3 materiale: wooden, plastic

Posizione 4 scopo: a shopping bag

Posizione 5 nome: a shopping bag

I nomi che si usano come attributi sono invariabili come gli aggettivi: the new bus station

Funzione predicativa

Gli aggettivi possono essere usati da soli dopo verbi come be (essere), seem (sembrare), look

(sembrare alla vista), taste (sembrare al gusto), sound (sembrare all’udito), smell (sembrare

all’olfatto), feel, (sentirsi, sembrare al tatto), become

This beach is fantastic! Questa spiaggia è fantastica!

She looks great. Ha un aspetto magnifico

I feel terribile. Mi sento malissimo.

You seem unhappy. Sembri scontento (infelice)

This taste good. Questo sembra buono.

Sue has become rich. Sue è diventata ricca.

Se si usa più di un aggettivo, si può separarli con la virgola e le congiunzioni.

Sue has become happy, rich and famous.

Un aggettivo preceduto da the indica un gruppo di persone nel suo insieme.

The young

the elderly

the rich

the poor

I giovani

gli anziani

i ricchi

i poveri

Alcuni aggettivi di nazionalità si comportano allo stesso modo:

The French the British

the English the Irish

the Spanish

I francesi

i britannici

gli inglesi

gli Irlandesi gli Spagnoli

16

Per altre nazionalità si usano i sostantivi plurali:

The Italians the Germans the Greeks the Turks

Gli italiani

I tedeschi

i greci

i turchi

the Poles

i polacchi

The Swedes

Gli svedesi

Problemi

Non confondere tra loro gli aggettivi che terminano i -ed e -ing

My work was tiring Il mio lavoro era faticoso

I was very tired. Io ero molto stanco

The film is boring. Il film è noioso

I am bored. Sono annoiato

Altre coppie di aggettivi dello stesso tipo sono:

interesting / interested = interessante / interessato

exciting / excited = eccitante / eccitato

embarassing / embarrassed = imbarazzante / imbarazzato

worrying / worried = preoccupante / preoccupato

L’aggettivo può essere seguito da one / ones, che sostituiscono rispettivamente un nome singolare

e un nome plurale

I like the blue sweater, but I don’t like the green one.

Mi piace il maglione blu, ma non mi piace quello verde.

I need a big notebook and two small one

Mi servono un quaderno grande e due piccoli

Gli avverbi

Gli avverbi di modo

La maggior parte degli avverbi di modo si ricavano aggiungendo -ly alla forma dell’aggettivo:

Slow

Quick

Careful

Bad

slowly

quickly

carefully

badly

Con gli aggettivi terminanti in -y questa si modifica in -i prima di aggiungere –ly

Angry

Easy

angrily

easily

Con gli aggettivi terminanti in -le si elimina la -e prima di aggiungere -ly.

Simple

Terrible

Gentle

simply

terribly

gently

17

La forma avverbiale di good è well

Alcuni avverbi hanno la stessa forma dell’aggettivo. Per esempio fast, hard, e late.

This train is very fast.

This train goes very fast

Questo treno è molto veloce.

Questo treno va forte

Our work was very hard.

We worked very hard

Il nostro lavoro era molto duro. Lavorammo duramente

Attenzione: la parola hardly non significa “duramente” ma “quasi non / a malapena”

I could hardly stand up. Riuscivo a malapena a stare in piedi

Le posizioni più frequenti dell’avverbio sono in fondo alla frase o prima del verbo principale

quando non si tratta di be).

Jim wrote the letter quickly.

Jim scrisse la lettera velocemente

Jim quickly wrote the letter

Tom ran up the stairs quickly. Tom quickly ran up the stairs

Tom è corso su per le scale a gran velocità.

Gli avverbi di frequenza vanno prima del verbo ordinario, ma dopo be nei verbi ausiliari.

Kate never arrives late. She is always early

Kate non arriva mai in ritardo. È sempre in anticipo.

Pronomi Personali

PERSONE

PRONOMI PERSONALI

SOGGETTO

1° persona singolare

PRONOMI PERSONALI

COMPLEMENTO

I

io

me

me/mi

2° persona singolare

3° persona singolare

3° persona singolare

3° persona singolare

you

he

she

it

tu

lui/egli

lei/ella

esso/essa

you

him

her

it

te/ti

lo/gli

la/le

lo/gli/la/le

1° persona plurale

2° persona plurale

3° persona plurale

we

you

they

noi

voi

loro/essi/esse

us

you

them

ce/ci

ve/vi

li/gli/le

In inglese il pronome personale soggetto è obbligatorio, mentre in italiano generalmente è

omesso, se non per dare risalto particolare al soggetto dell’azione.

Where are you goingi? – Dove vai?

Il pronome personale complemento si trova sempre dopo il verbo: I won’t tell her. –Non glielo dirò.

La forma soggetto o la forma complemento del pronome è imposta dalla funzione che esso occupa

nella frase.

18

Present Simple

Il presente di to be = essere

To be è un verbo irregolare, al tempo presente si coniuga così:

Italiano

Inglese

Forma contratta

io sono

tu sei

egli / ella / esso è

noi siamo

voi siete

essi sono

I’m

You’re

He’s / she’s / it’s

We’re

You’re

They’re

I am

You are

He is / She is / It is

We are

You are

They are

La forma negativa si ottiene aggiungendo not:

I am not

You are not

He / she / it is not

We are not

You are not

They are not

(forma contratta)

I’m not

You aren’t

he / she / it isn’t

We aren’t

You aren’t

They aren’t

Alcuni esempi: I’m tired. Sono stanco

Tom and Sue aren’t Welsh. Tom e Sue non sono gallesi.

They aren’t in the classroom. Essi non sono in classe.

The banks are not open today. Le banche non sono aperte oggi.

La forma interrogativa del Present Simple di to be si ottiene invertendo la posizione del

soggetto e del verbo:

Am I…?

Are you…? /

Is he / she / it…?

Are we…?

Are you…?

Are they…?

Esempi: Are your parents at home? I tuoi genitori sono in casa?

Is your father a doctor? Tuo padre è un medico?

Is this supermarket new? È nuovo questo supermercato?

Alcune forme di to be corrispondono a forme italiane che si costruiscono con il verbo ‘avere’:

avere paura - be afraid; avere freddo - be cold; avere fame - be hungry; avere sete - be thirsty; avere fretta

- be in a hurry; avere ragione - be right; avere torto - be wrong

19

Esempi:

Be 15 years old

Avere 15 anni

I’m hot but I’m not thirsty Ho caldo ma non ho sete

I think you’re right

Penso che tu abbia ragione

My grandmother is 89 Mia nonna ha 89 anni

Il Present Simple dei verbi principali

Il Present Simple si forma con l’infinito del verbo senza il to. Consideriamo il verbo to work

(lavorare):

I work

you work

he / she / it works

we work

you work

they work

Alla terza persona singolare si aggiunge sempre una s.

[Con i verbi che terminano in o, s, ch, sh, x, si aggiunge – es: She works, he goes, Bob watches, she misses.

I verbi in –y preceduta da consonante terminano in -ies alla terza persona singolare: he studies, Bill tries,

she cries.

Quelli invece che terminano in –y preceduta da vocale si comportano normalmente: he plays / she plays / it

plays]

Quando si usa il Present Simple

• Il Present Simple si usa per descrivere degli eventi ricorrenti, delle azioni abituali:

I usually get up at 7.30. Mi alzo di solito alle 7.30

The bus leaves every morning at 6.00. L’autobus parte ogni mattina alle 6.00.

• Il Present Simple si usa per descrivere fatti personali:

Liz plays basketball. Liz gioca a basket

Tom eats cornflakes for breakfast. Tom mangia i cornflakes a colazione.

•

Il Present Simple si usa per descrivere realtà che sono sempre vere:

The sun rises in the east. Il sole sorge ad est.

Bees make honey. Le api fanno il miele.

Con il Present Simple spesso si usano gli avverbi di frequenza:

Often – spesso; always – sempre; usually – di solito, solitamente; rarely – raramente, di rado;

never – mai; sometimes – alle volte; ecc.

In una frase gli avverbi di frequenza si trovano sempre fra il soggetto e il verbo ordinario; soltanto

con to be sono posizionati dopo il verbo.

Esempi:

My bus never arrives on time. Il mio autobus non arriva mai in tempo.

Jim is usually late. Jim è solitamente in ritardo.

20

La forma negativa del Present Simple

La forma negativa del Present Simple dei verbi regolari si costruisce con do not più il verbo

all’infinito senza to.

Soggetto + do not + verbo all’infinito senza to

I do not work

forma contratta

You do not work

He / she / it does not work

We do not work

You do not work

They do not work

I dont’ work

You don’t work

He / she / it doesn’t work

We don’t work

You don’t work

They don’t work

La s della terza persona va sull’ausiliare does.

La forma interrogativa del Present Simple

La forma interrogativa del Present Simple dei verbi regolari si costruisce con do più il soggetto più il

verbo all’infinito senza il to.

Do + soggetto + verbo all’infinito senza to

Do I work?

Do you work?

Does he / she / it work?

Do we work? Do you work?

Do they work?

La forma interrogativa negativa del Present Simple

Si costruisce con do più not più il soggetto seguito dall’infinito senza il to:

Do not I work?

forma contratta Don’t I work?

Do not you work?

Don’t you work?

Does not he / she / it work?

Doesn’t he / she / it work?

Do not we work?

Don’t we work?

Do not you work?

Don’t you work?

Do not they work?

Don’t they work?

Nelle frasi interrogative la costruzione Do / does + soggetto + verbo all’infinito senza to si ritrova

anche con i pronomi interrogativi:

What do you want? Cosa vuoi? When do you leave? Quando parti?

How many do you want? Quanti ne vuoi? Where does she live? Dove vive lei?

Tuttavia, se il pronome interrogativo funge da soggetto non si usa do / does:

Who lives here? Chi vive qui? Which of you speaks English? Chi di voi parla inglese?

21

Pronomi interrogativi: What (cosa); when (quando); why (perché nelle frasi interrogative); where

(dove); how (come, quanto, quanti, in che modo); who (chi); which (chi fra due o più persone).

Il Present Simple di to have (got)

Come to be anche il verbo to have (avere) è un verbo irregolare.

Spesso nell’inglese britannico il verbo to have è seguito da got, e si costruisce al presente in questo

modo:

I have got

I’ve got

You have got

You’ve got

He / she / it / has got

He / she / it has got

We have got

We’ve got

You have got

You’ve got

They have got

They’ve got

Forma negativa:

I haven’t got

You haven’t got

He / she / it hasn’t got

We haven’t got

You haven’t got

They haven’t got

Forma interrogativa:

Have I got?

Have you got?

Has he / she / it got?

Have we got?

Have you got?

Have they got?

Nell’anglo-americano si può usare il verbo to have senza got. In questo caso si costruisce come un

verbo regolare, quindi utilizzando l’ausiliare to do nella forma negativa e nella forma interrogativa:

I / you / we / they have

I / you / we / they don’t have

Do I / you / we / they have?

Esempio:

I have a car.

I don’t have a car.

Do you have a car?

He / she / it has

He / she / it doesn’t have

Does he / she / it have?

He has a car

He doesn’t has a car

Does he have a car?

22

Present Continuous

Il Present Continuos si forma con il presente del verbo essere (to be) più l’infinito del verbo nella

forma in -ing.

Present Simple di to be + infinito del verbo in -ing

I am working

She is dreaming

You are reading

Io sto lavorando

Lei sta sognando

Voi state leggendo

I verbi che terminano con la vocale –e, la perdono e acquistano –ing.

Ad esempio:

write – writing; smoke – smoking; bite – biting; choose – choosing; smile – smiling; ecc.

I verbi formati da una sola sillaba che terminano con una consonante preceduta da una sola

vocale, raddoppiano la consonante:

sit – sitting; swim – swimming; dig – digging; cut – cutting;

I verbi che terminano con -ie cambiano –ie in –y e aggiungono –ing.

Lie – lying; tie – tying; die – dying;

Quando si usa il Present Continuous

• 1) Il Present Continuos si usa quando per esprimere qualcosa che sta accadendo, o sta

quasi per accadere, nel momento in cui si parla:

The pot is bowling. Can you turn it off, please?

La pentola sta bollendo. Puoi spegnere per piacere, per piacere?

Where is Tom? He’s playing tennis. Dov’è Tom? Sta giocando a tennis.

•

2) Il Present Continuous può essere usato per una situazione temporanea:

I’m living with some friends until I can find a flat.

Vivo con dei miei amici finché non riesco a trovare un appartamento.

•

3) Il Present Continuous si può usare per parlare di eventi già programmati, di piani già

decisi per il futuro. In questi casi il Present Continuous è accompagnato da un

complemento di tempo futuro, a volte lo si traduce in italiano con il presente indicativo:

Paul is leaving early tomorrow morning. Paul parte presto domani mattina.

My parents are buying me a mountain bike for my birthday.

I miei genitori mi comprano una mountain bike per il mio compleanno.

•

4) Si può usare il Present Continuous quando si ci lamenta di azioni o di situazioni ricorrenti:

You are always forgetting your keys!

Ti dimentichi sempre le chiavi!

23

La forma negativa del Present Continuous

La forma negativa del Present Continuous si costruisce aggiungendo la negazione not alle voci di to

be:

I am not drinking

You are not listening

He / she / it is not taking

We are not watching

You are not speaking

They are not winning

I’m not drinking

You aren’t listening

He / she / it isn’t taking

We aren’t watching

You aren’t speaking

They aren’t winning

La forma interrogativa del Present Continuous

La forma interrogativa del Present Continuous si costruisce invertendo le voci di to be:

Am I drinking?

Are you listening?

Is he / she / it not taking?

Are we not watching?

Are you speaking?

Are they winning?

Domande specifiche con i pronomi interrogativi:

What are you cooking?

Why are they crying?

Who is sleeping?

Present Continuous (I am doing) or Present Simple (I do)?

Il Present Continuos (I am doing) si usa quando per parlare di qualcosa che sta accadendo o sta

quasi per accadere nel momento in cui si parla.

Quando l’azione avviene in quel preciso momento:

La pentola sta bollendo. Puoi spegnere per piacere, per piacere? The pot is bowling. Can you

turn it off, please?

Dov’è Tom? Sta giocando a tennis Where is Tom? He’s playing tennis.

Il Present Continuous può essere usato per una situazione temporanea:

Vivo con dei miei amici finché non riesco a trovare un appartamento. I’m living with some

friends until I can find a flat.

Quella macchina non funziona. Si è rotta stamattina. That machine isn’t working. It broke down

this morning.

24

Il Present Continuous può essere usato per il futuro, per esprimere un’idea già programmata o

un progetto futuro: Are you doing anything tonight?

Present Simple, invece, si usa per riferire di qualcosa in generale, qualcosa che accade di

frequente o qualcosa di personale:

L’acqua bolle a 100 gradi. Water boils 100 degrees centigrade (Celsius).

Tom gioca a tennis ogni sabato. Tom plays tennis every Saturday.

Cosa fai generalmente nei weekends? What do you usually do at weekends?

Il Present Simple si usa anche quando ci riferiamo a orari, programmi, ad esempio per i trasporti

pubblici, per il cinema, ecc.

What time does film begin?

The train leaves London at 10.30 and arrives in Oxford at 11.45.

The football match starts at 8 o’clock.

Tomorrow is Wednesday.

Ma non lo usiamo per gli appuntamenti personali: What time are you meeting Ann?

• La forma del presente indicativo in italiano può corrispondere sia al Present Simple che al

Present Continuous:

(in generale, di solito)

I work

(ora, in questo momento) I am working

(domani, sabato prossimo) I’m working tomorrow

Lavoro

Sto lavorando

Domani lavoro

Alcuni verbi che possono essere usati soltanto nella forma del Present Simple e non nel Present

Continuous.

Si chiamano verbi di stato perché descrivono:

a) condizioni permanenti, non azioni. Per esempio: be, belong to, contain, cost, depend on, have,

own

b) opinioni o stati d’animo. Per esempio: think, believe, forget, feel, like, hate, know, prefer,

understand

Do you like London?

He doesn’t understand

These shoes belong to me.

What do you think Tom will do?

but What are you thinking about?

Verbi comunemente usati come verbi di stato al Present Simple, cambiano significato quando si

usano come verbi di azione al Present Continuous:

I have two sisters (condizione permanente) Ho due sorelle.

I’m having problems with this computer (situazione o azione temporanea)

25

Past Simple

Il Past Simple dei verbi regolari

Si forma aggiungendo il suffisso - ed all’infinito senza to.

to work

I worked

Questa forma rimane invariata per tutte le persone:

I loved

you loved

he she it loved

we loved

you loved

they loved

[I verbi che terminano in -e al Past Simple prendono solo -d.

to love

I loved the music

La musica mi è piaciuta.

I verbi che terminano in –y preceduta da vocale al Past Simple prendono normalmente il suffisso -ed

to enjoy

I enjoyed the film

Il film mi è piaciuto.

I verbi che terminano in -y preceduta da consonante, nella forma del Past Simple la vocale -y cade e

prendono -ied

To try

tried

To cry

cried

I verbi che terminano con una sola consonante preceduta da una vocale accentata raddoppiano la

consonante finale:

to regret

regretted

to fit

fitted

to stop

stopped ]

Il Past Simple dei verbi irregolari si memorizza con lo studio e con l’uso.

Alcuni esempi:

to eat ate eaten

to drink drank drunk

to wake woke woken

La forma negativa del Past Simple

La forma negativa del Past Simple si costruisce con il soggetto, l’ausiliare did (Past Simple di to do)

più la negazione not e l’infinito del verbo senza il to. Nel parlato e negli scritti informali did not si

contrae in didn’t.

The coat didn’t fit me

Il cappotto non mi stava

Carol didn’t eat very much Carol non mangiò molto

26

La forma interrogativa del Past Simple

La forma interrogativa si costruisce con l’ausiliare did (Past Simple di to do) più il soggetto seguito

dall’infinito del verbo senza il to

Did you enjoy the film?

Ti è piaciuto il film?

What did you do yesterday?

Cosa hai fatto ieri?

Did you drink the milk?

Hai bevuto il latte?

Did you eat pizza?

Hai mangiato la pizza?

Why did she leave?

Perchè è partita?

Non si usa did nelle frasi interrogative quando What / Who fungono da soggetto:

Who phoned? Chi ha telefonato?

Il Past Simple di to be

Il verbo to be è irregolare. Il paradigma è to be (Infinitive) was / were (Past Simple) been (Past

Participle).

Le voci del Past Simple sono:

I was

you were

he she it was

we were

you were

they were

Nella forma negativa si aggiunge not:

I was not (forma contratta)

you were not

he she it was not

we were not

you were not

They were not

I wasn’t

you weren’t

he she it wasn’t

we weren’t

you weren’t

they weren’t

Esempi:

It was very cold last Sunday

Era molto freddo domenica scorsa

I wasn’t too tired during last weekend Non ero troppo stanco durante l’ultimo weekend

Where were you yesterday afternoon? Dove eri / eravate ieri pomeriggio?

27

Past Simple di to have

Il verbo avere to have è irregolare. Il paradigma è: to have (Infinitive) had (Past Simple) had (Past

Participle). Di solito non si usa got nel Past simple.

I / you/ he / she / it / we / you / they had

La forma negativa

Per la forma negativa si usa l’ausiliare did e la negazione not più l’infinito del verbo senza to

I did not have any money (contratta)

She did not find a job

I didn’t have any money

She didn’t find a job

Non avevo soldi

Non ha trovato un lavoro

La forma interrogativa

La forma interrogativa del Past Simple di to have si ottiene invertendo l’ausiliare did con il soggetto

Did you have any questions?

Avevate domande?

Did she have her passport?

Ha avuto il suo passaporto?

Altri esempi:

Ann had a car when she was a student.

Did you write the report yesterday? No, I didn’t have time.

What time did you have supper last night?

Uso del Past Simple

Il Past Simple descrive azioni, situazioni o stati determinati nel passato.

Può essere accompagnato da un complemento che indica un tempo completamente trascorso. Si

traduce molto spesso con il passato prossimo italiano.

I enjoyed the film we saw last night

We listened to some new CDs yesterday afternoon

Il Past Simple descrive anche azioni abituali del passato. In tal caso, si traduce con l’imperfetto.

Every day we got up early and went to the beach

Altri esempi:

- Ann: Did you go out last night?

- Tom: Yes, I went to the cinema. But I didn’t enjoy the film.

When did Mr. Edwards die?

What did you do at the week-end?

We didn’t invite her to the party, so she didn’t come.

Why didn’t you phone me on Tuesday?

Come precedentemente menzionato si usa did con il verbo have:

Did you have time to write the letter?

I didn’t have enough money to buy anything to eat.

Ma non si usa did con be:

Tom was at work yesterday

They weren’t able to come because they were very busy.

Why were you so angry?

28

Past Continuous

Il Past Continuous si forma con il passato di to be più il verbo in forma –ing

Soggetto + Past Simple di to be + il verbo in -ing

I was sleeping

You were laughing

He was driving

She was crying

We were eating

You were writing

They were sitting there

stavo dormendo

tu stavi ridendo

stavo guidando

stava piangendo

stavamo mangiando

voi stavate scrivendo

loro erano seduti là

La forma negativa del Past Continuous

Le forme negative del Past Continuous si formano aggiungendo not alla voce di be. Was not e were

not si contraggono in wasn’t e weren’t.

Soggetto + Past Simple di to be + not + il verbo in -ing

I wasn’t listening

He wasn’t listening

They weren’t looking

La forma interrogativa del Past Continuous

Nelle domande al Past Continuous s’inverte la posizione della voce di be

Past Simple di to be + soggetto + il verbo in -ing

Was I sleeping? Were you walking? Was he reading?

Was she driving? Were we writing? Were they leaving?

• Domande specifiche (Wh-)

What were you doing? Why was he eating? Who was laughing?

Uso del Past Continuous

Il Past Continuous descrive un’azione in corso in un momento del passato.

Spesso l’azione in corso fa da contesto ad un fatto improvviso:

Azione in corso

fatto in corso

I was having my lunch

Stavo pranzando

While I was waiting for the bus,

Mentre aspettavo

when Ruth phoned

quando Ruth chiamò

I met Karen

ho incontrato Karen

29

Come si vede nel secondo esempio, il Past Continuous si traduce con l’imperfetto semplice

(aspettavo) o con stare più il gerundio (stavo aspettando).

Il Past Continuous descrive anche una serie di situazioni che fanno da contesto ad un fatto o ad

un’azione svolta nel passato.

The airport was full of people. Some were sleeping on the benches, some were shopping, others were

reading. Everyone was waiting for news of the delayed plane.

L’aeroporto era pieno di gente. Alcuni dormivano sui sedili, alcuni facevano acquisti, altri leggevano. Tutti

stavano aspettando l’aereo in ritardo.

Il Past Continuous si usa per descrivere due azioni contemporaneamente:

While Jim was cooking, David was phoning a friend.

Mentre Jim cucinava stava cucinando, David telefonava / stava telefonando a un amico / amica.

Il Past Continuous non ci dice se l’azione nel passato si è conclusa:

Tom was cooking the dinner (Past Continuous) – (He was cooking the dinner and we don’t know whether he

finished cooking it).

Tom cooked the dinner (Past Simple) – (He began and finished it).

[Il Past Simple indica un’azione che si è conclusa in un tempo determinato.

I arrived here two hours ago / in September / last week / at 6.00 pm.

Sono arrivata / arrivato qui due ore fa / a settembre / la settimana scorsa/ alle 6.00 di sera.]

Il Past continuous indica un’azione che era in corso nel passato

While we were waiting for the train, it started to rain. Mentre aspettavamo, incominciò a piovere.

I cut my finger when I was peeling the potatoes. Mi sono tagliato un dito quando / mentre

sbucciavo le patate.

• Per le espressioni di un tempo che si usano nei racconti.

Attenzione: alcuni verbi che normalmente non vengono usati nella forma progressiva (Continuous

Tenses). Ad esempio:

want; like; think; belong; know; suppose; remember; need; love; see; realise; mean; forget

prefer; hate; hear; believe; understand; seem

30

There is / There are

There is

C’è

There are

Ci sono

In queste espressioni THERE, pur non essendo grammaticalmente il soggetto* del verbo to be (è

un avverbio di luogo = lì), si comporta come se fosse il soggetto.

Forma

Forma affermativa

Forma negativa

Forma interrogativa

Short answers

(risposte brevi)

Costruzione

Esempio

There is (there's)

There is a book on the

desk.

(C'è un libro sulla

scrivania.)

There are

There are some books on

the desk.

(Ci sono dei libri sulla

scrivania.)

There is not (there

isn’t)

There isn't any snow.

(Non c'è neve.)

There are not (there

aren’t)

There aren't any students

in the classroom.

(Non ci sono studenti

nell'aula.)

Is there…?

Is there anybody at

home?

(C'è qualcuno in casa?)

Are there…?

Are there any letters for

Mark?

(Ci sono lettere per

Mark?)

Yes, there is/are

Is there a good

restaurant near here?

(C'è un buon ristorante

qui vicino?)

No, there isn't/aren't

•

•

Yes, there is.

No, there isn't.

La stessa costruzione può essere utilizzata anche per gli altri tempi del verbo to be.

31

Il superlativo assoluto

In inglese il superlativo assoluto dell’aggettivo (grandissimo, bellissimo, ecc.) si esprime usando

very (molto), really (veramente), extremely (estremamente), terribly / awfully (terribilmente) o

altri avverbi.

Si può dire

very happy, really happy, extremely happy molto felice, veramente felice, felicissimo

The film was terribly / awfully / really good Il film è stato bellissimo / veramente bello

Comparativo e superlativo degli aggettivi

Con gli aggettivi monosillabici si forma il comparativo aggiungendo -er e il superlativo aggiungendo

-est. Nei monosillabi che terminano con una sola consonante preceduta da una sola vocale, questa

si raddoppia. Negli aggettivi terminanti in -y preceduta da consonante si cambia -y in -i.

Comparativo: long- longer

big – bigger

dry –drier

Superlativo: long – the longest

big – the biggest

dry – the driest

Con gli aggettivi di due o più sillabe si forma il comparativo con more (più) e il superlativo con the

most (il/ la/ i/ le)

Comparativo: modern -more modern

interesting - more interesting

Superlativo: modern - the most modern interesting - the most interesting

Gli aggettivi bisillabici terminanti in –y si comportano come monosillabici (-er / -est).

Happy – happier

the happiest

easy –easier the easiest

Altri aggettivi bisillabici possono essere usati in entrambi i modi:

common – commoner

the commonest

more common

the most common

Comparativo e superlativo degli avverbi

Di norma gli avverbi formano il comparativo con more e il superlativo con the most.

Can you work more quickly? Puoi / Potete lavorare alla svelta?

Jane works the most quickly. Jane lavora più rapidamente di tutti

Forme irregolari

Grado positivo

Comparativo

Superlativo

good (buono)

better (migliore)

the best (il migliore)

well (buono)

better (meglio)

the best (il meglio)

bad (cattivo)

worse (peggiore)

the worst (il peggiore)

badly (male)

worse (peggiore)

the worst (il peggiore)

far (lontano)

farther / further (più lontano)

the farthest / the furthest (il più lontano)

little (poco)

less (meno)

the least (il meno)

much / many (molto/molti) more (più)

the most (il più)

32

Il comparativo / superlativo di old ha due forme: una regolare (older / the oldest - più vecchio, il

più vecchio) e una forma irregolare, che si usa parlando di figli, fratelli o sorelle.

This is my elder brother.

Jane is their eldest daughter

Questo è il mio fratello maggiore. Jane è la loro figlia maggiore

Gli avverbi che hanno la stessa forma dell’aggettivo (fast - veloce / velocemente, hard - duro /

duramente, late - in ritardo/ tardi, early - precoce / presto, e far - lontano) prendono - er / -est e

non more / the most. Nel parlato quotidiano si tende ad usare come avverbi anche gli aggettivi

loud, quick e slow.

Could you drive more slowly, please?

Could you drive slower, please? (informale)

Comparativi e superlativi: il secondo termine

Si usano le forme comparative per confrontare due elementi tra loro. Il secondo termine è

preceduto da than.

Mary is better than Monica.

Maria è migliore di Monica.

Mary is a better player than Monica.

Mary è una giocatrice migliore di Monica.

Quando si confrontano due azioni, si usa un ausiliare per non ripetere il verbo.

Mary plays better than Monica does.

Mary gioca meglio di Monica

You’ve done more work than I have.

Tu hai lavorato più di me.

Si usa il superlativo relativo per confrontare un elemento con tutti gli altri. Il termine di riferimento

del superlativo può essere preceduto da –in (+ insieme o luogo), that (+ frase) oppure of o among

(negli altri casi). That si può omettere.

Sue is the best player in the team / in the world.

Sue è la miglior giocatrice della squadra / del mondo.

Sue is the best player (that) I know.

Sue è la migliore giocatrice che io conosca.

Sue is the best of / among the students.

Sue è la migliore degli / fra gli studenti.

Come si vede nell’ultimo esempio, il superlativo può essere usato da solo.

Sue is the greatest!

Sue è la più grande!

33

Forme possessive

1 ) I verbi che esprimono un possesso o un’appartenenza.

Per esprimere possesso o appartenenza si possono usare forme verbali apposite. Ecco le più frequenti:

have (got) avere

Own possedere/ essere proprietari di

Belong to appartenere a

Esempi: I’ve got a new car. Ho una macchina nuova

They own a lot of flats. Posseggono molti appartamenti.

This mobile belongs to Jim. Questo telefonino appartiene a Jim.

2) Gli aggettivi e i Pronomi possessivi

Persona

Pronome

Aggettivo

1a singolare

mine

my

2a singolare

yours

your

3a singolare (femminile)

hers

her

3a singolare (maschile)

his

his

3a singolare (neutra)

its

its

1a plurale

ours

our

2a plurale

yours

your

3a plurale

theirs

their

In inglese gli aggettivi possessivi sono invariabili di genere e di numero. (my – il mio, la mia, i miei,

le mie). Gli aggettivi his, her, its (il suo / la sua/ i suoi / le sue), si riferiscono rispettivamente a un

possessore maschile, femminile, neutro.

Peter and his children play baseball every Sunday.

Peter e i suoi bambini giocano a baseball ogni domenica.

Clara and her children often watch TV together.

Clara e I suoi bambini spesso guardano insieme la TV.

That is a shark. Look at its teeth.

Questo è un o squalo. Guarda i suoi denti.

34

I possessivi possono essere rinforzati con own (proprio).

Why don’t you mind your own business?

Perché non ti fai gli affair tuoi? That isn’t their own boat. They borrowed it from a friend.

Questa non è la loro barca. L’hanno presa in prestito da un loro amico.

I pronomi possessivi si usano da soli al posto di un aggettivo possessivo e di un nome

Questa è la mia bici This is my bike.

Questa bici è mia. This bike is mine.

A parte mine e his, i pronomi possessivi si ricavano aggiungendo la s all’aggettivo possessivo. In

pratica il pronome corrispondente ad its non esiste.

Whose dictionary is this? Is it yours or mine?

Yours is on the table. This is mine.

Whose?

L’espressione interrogativa Whose? (Di chi?) è una forma possessiva e può essere usata come

aggettivo o come pronome.

Aggettivo: Whose ruler is this? Di chi è questo righello.

Pronome: Whose is this ruler? Di chi è questo righello.

Genitivo sassone

Viene spesso usato in inglese per indicare il possesso, soprattutto quando il possessore è

- persona o animale

Es: My brother’s car is red ("La macchina di mio fratello è rossa")

- nazione o città

Es: London’s squares are large ("Le piazze di Londra sono grandi")

- avverbi di tempo

Es: Today’s match is at 4.00 ("La partita di oggi è alle 4")

- espressione di distanza e peso

Es: It’s a 700 kilometers’ journey ( "E’ un viaggio di 700 Km")

- pronomi indefiniti

Es: Everyone’s body temperature is 37° C ("La temperatura corporea di tutti è di

37° C")

Il GENITIVO SASSONE si costruisce secondo il seguente schema:

possessore + ’s + persona, animale o cosa posseduta (senza articolo)

Quando il possessore termina in –s, può essere seguito solo dall’apostrofo senza s:

Es: It’s a 700 kilometers’ journey ("E’ un viaggio di 700 Km")

Quando vi sono più possessori:

- si aggiunge ’s solo all’ultimo possessore se il possesso è condiviso

Es: John and Mary’s parents are in Sweden. ("I genitori di John e Mary sono in

Svezia)

35

- si aggiunge ’s solo a ciascun possessore se il possesso è individuale

Es: John’s and Mary’s parents are in Sweden. ("I genitori di John e quelli di Mary

sono in Svezia)

I seguenti sostantivi sono di solito omessi quando hanno la funzione di "cosa

posseduta":

- house

- restaurant

- shop / store

- hospital

- church / cathedral

- office

Es: She is going to Bob’s ("Sta andando a casa di Bob")

Es: Where is the nearest chemist’s ? ("Dov’è la farmacia più vicina ?")

Es: We visited St. Paul’s ("Abbiamo visitato la cattedrale di St. Paul")

36

Some, Any, No

SOME

Alcuni, un po’ di, dei/delle, in frasi affermative.

Some può essere utilizzato sia come aggettivo che come pronome

indefinito. Quando è aggettivo è seguito da un sostantivo che, se si

tratta di un countable, deve essere messo al plurale. Quando è

pronome non è seguito da un nome, ma lo sottintende.

There is some milk in the fridge. (C'è del latte nel frigo.)

In questo caso some è aggettivo, perché è seguito dal nome milk.

There is some. (Ce n'è un po’.)

In questo caso some è pronome, sottintende il nome milk.

Some si usa anche in frasi interrogative quando si offre qualcosa o

si

chiede

per

avere

qualcosa.

Would

you

like

some

tea?

(Vuoi

del

tè?)

Can I have some sugar, please? (Posso avere dello zucchero, per

favore?)

ANY

1. Alcuni, un po’ di, dei/delle, in frasi interrogative e negative.

Come some, anche any può essere sia aggettivo che

pronome. Quando è seguito da un sostantivo countable,

questo deve essere messo al plurale.

Is there any milk in the fridge? (C'è del latte nel frigo?)

There isn't any milk in the fridge. (Non c'è latte nel frigo.)

There isn't any. (Non ce n'è.)

Are there any eggs? (Ci sono delle uova?)

There aren't any eggs. (Non ci sono uova)

There aren't any. (Non ce ne sono.)

2. In frasi affermative, any significa qualunque, qualsiasi.

Quando è utilizzato con questo significato ed è aggettivo, è

sempre seguito da un sostantivo singolare.

Which magazine shall I buy? (Quale rivista devo comprare?)

Any magazine, I don't mind. (Qualunque rivista, non importa.)

NO

Nessuno, nessuna, niente, vuole sempre il verbo in forma

affermativa.

No è solo aggettivo, cioè deve sempre essere seguito da un

sostantivo.

There is no milk in the fridge. (Non c'è latte nel frigo.)

There are no books on the desk. (Non ci sono libri sulla scrivania.)

NONE

Nessuno, nessuna, niente, pronome, cioè non seguito da

37

sostantivo.

How many English books have you read? (Quanti libri inglesi hai

letto?

I've read none (= no English books). (Non ne ho letto nessuno.)

Nota

Nelle frasi negative sono possibili due costruzioni:

Non c'è nessun libro sulla scrivania.

1. Any con verbo in forma negativa: There aren't any books on the desk.

2. No con verbo affermativo: There are no books on the desk.

Forme composte di Some, Any, No

Si possono ottenere diversi sostantivi unendo i quantificatori some, any e no con thing, body, one

e where. Per cui avremo:

1. Something, Someone, Somebody, Somewhere (qualcosa, qualcuno, qualcuno, qualche

parte)

2. Anything, Anyone, Anybody, Anywhere (qualsiasi cosa, chiunque, chiunque, ovunque)

3. Nothing, none, nobody, nowhere (nulla, nessuno, nessuno, da nessuna parte)

Notare che "-body" si usa riguardo le persone, mentre "-thing" con le cose. "-one" invece è la

forma più generica. Si usano allo stesso modo di Some e Any.

Some con le frasi positive e le domande (di cui si conosce la risposta), Any con le frasi negative e le

domande (di cui non si conosce la risposta) e No con frasi negative.

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

I saw something outside - Ho visto qualcosa fuori

Someone was here - Qualcuno era qui

It must be somewhere - Deve essere da qualche parte

Are you looking for someone? - Stai cercando qualcuno? (=so che lo stai facendo)

Have you lost something? - Hai perso qualcosa? (=so che lo hai fatto)

Is there anything wrong in the project? - C'è qualcosa di sbagliato nel progetto? (domanda

reale)

Did you go anywhere? - Andasti da qualche parte? (domanda reale)

Con le frasi negative si può usare sia any... che no...; il secondo dà più enfasi alla frase. Ad

esempio:

•

•

I do not know anything about it - Non so nulla riguardo di questo. (= neutrale)

I know nothing about it - Non so nulla di questo (= più enfasi, ad esempio di posizione

difensiva)

38

Notare che No- rende negativa la frase, per cui se viene usato nothing/nowhere/none/nobody il

verbo va alla forma affermativa (senza not).

Esempio: I hate nobody - Non odio nessuno

Any usato nelle frasi positive assume il significato di "non importa quale"/"non importa chi"/"non

importa che cosa".

Esempio:

•

•

•

You can ask me anything - Puoi chiedermi qualsiasi cosa

You can invite anybody to dinner - Puoi invitare chiunque tu voglia a cena

I can listen to any of his CDs - Posso ascoltare qualsiasi suo CD.

Say e Tell

Sia to tell che to say significano dire, ma vengono usati in modo diverso.

Say - said - said

Significato

Dire, quando non è espressa la persona a cui

si parla.

Se viene espressa la persona a cui si parla,

questa è preceduta dalla preposizione to. (In

questo caso, tuttavia, si preferisce usare to

tell.)

Esempio

He said he was tired.

(Disse che era stanco.)

What did you say to him?/what

did you tell him? (Che cosa gli

hai detto?)

Si usa to say nelle seguenti espressioni:

To say hello/goodbye: salutare

He left without saying goodbye.

(Se ne andò senza salutare)

To say yes/no: dire di si/no

That is to say: cioè

She said yes.

(Disse di si.)

To say sorry: chiedere scusa

39

Tell - told - told

Significato

Raccontare

Esempio

To tell a story

(Raccontare una storia)

To tell a joke

(Raccontare una barzelletta)

Dire, quando viene espressa la persona a cui

si parla.

Si costruisce nel seguente modo:

Dire qualcosa a qualcuno

To tell someone something

Mark told his friend he was tired.

(La costruzione to tell something to someone (Mark disse al suo amico che era

è corretta ma meno comune.)

stanco.)

Alcune espressioni idiomatiche di uso

quotidiano:

Tell me: dimmi, come introduzione di una

frase più lunga

So, tell me, what did he say?

(Allora, dimmi, che cosa ha detto?)

Go ahead, tell me!

(Dai, dimmi tutto!)

I told you so: te l'avevo detto

I tell you: credimi, te lo dico io

I tell you, that guy is crazy!

I told you a thousand times: te l'ho già detto (Credimi, quello è matto!)

un'infinità di volte

Si usa il verbo to tell nelle seguenti

espressioni, anche se non viene espressa la

persona a cui si parla:

He can't tell the time yet.

(Non sa ancora leggere l'ora.)

Don't tell lies! (Non dire bugie!)

To tell the time: dire/leggere l'ora

To tell a lie:dire una bugia

Tell me the truth. (Dimmi la

verità.)

To tell the truth: dire la verità

He told the child off. (Sgridò il

bambino.)

To tell off: sgridare

I can't tell the difference between

the two versions.

(Non so dire la differenza fra le

due versioni.)

To tell the difference: dire la differenza

40

Much, many, (a) little, (a) few

Gli indefinite di quantità servono ad indicare una quantità piò o meno grande. Il loro uso dipende

dal nome al quale si riferiscono, a seconda che sia numerabile o non numerabile.

Da usare solo con sostantivi

non numerabili

Usabili indifferentemente

Da usare solo con sostantivi

numerabili

How much?

How much? or How many?

How many?

a little - un po', una piccola

parte

no/none - nessuno

a few - un po', alcuni

a bit (of) - un po'

not any - nessuno

a number (of) - un piccolo

numero di

-

some (any) - un po'

several - diversi, svariati

a great deal of (una grande

quantità di)

a lot of - molto, un sacco di

a large number of - molti, un

grande numero di

a large amount of (un grande plenty of - molto, una grande

ammontare di)

abbondanza di

a great number of - molti, un

grande numero di

-

-

lots of - molto, un sacco di

Inoltre si usano much (molto) e many (molti) nelle domande e nelle frasi negative. Gli stessi sono

comunque usati nell'inglese formale scritto anche nelle frasi affermative.

Much si usa con i sostantivi singolari e non numerabili, many con i numerabili plurali.

Con la question word "how" formano le domande "quanto" e "quanti".

Es: How much money have you got? - Quanti soldi hai?

I haven't much money - Non ho molti soldi

How many films have you seen? - Quanti film hai visto?

I haven't seen many film - Non ho visto molti film.

Possono essere anche usati prima di much e many gli intensificatori too, (not) so, e (not) as.

I have seen too many films - Ho visto troppi film

I had never thought you had seen so many films - Non avevo mai pensato che avevi visto così tanti film

There's not so many cars to fix - Non ci sono così tante auto da riparare.

41

Make e Do

Sia to do che to make significano fare, ma vengono usati in circostanze diverse.

Make - made - made

Quando si usa

To make significa fare nel senso di produrre, creare,

preparare.

Esempio

She's making a cake.

(Sta facendo una torta.)

She's making breakfast.

(Sta preparando la colazione.)

To be made from…Essere fatto con (a partire da)…

Made in Germany

(Fabbricato/prodotto in Germania)

To be made of…Essere fatto di…

Wine is made from grapes.

(Il vino è fatto con l'uva.)

That skirt is made of cotton.

(Quella gonna è di cotone.)

Si usa to make nelle seguenti espressioni:

To make a mistake: fare un errore

To make a phone call: fare una telefonata

You make too many mistakes.

(Fai troppi errori.)

To make a difference: fare differenza

It doesn't make any difference.

(Non fa alcuna differenza.)

To make friends: farsi degli amici

To make money: fare soldi

I made a lot of friends last summer.

(Mi sono fatto molti amici l'estate

scorsa.)

To make a decision: prendere una decisione

To make an effort: fare uno sforzo

Far fare qualcosa a qualcuno:

To make someone do something

Nota: si utilizza anche la costruzione passiva, in cui la

persona a cui si fa fare qualcosa diventa soggetto e il

verbo che segue va all'Infinito (cioè con il to), anziché

nella Forma Base (senza to).

I can't make a decision.

(Non riesco a prendere una

decisione.)

The teacher made me read that

book.

(L'insegnante mi fece leggere quel

libro.)

42

Do - did - done

Quando si usa

To do significa fare in generale, senza specificare

esattamente di che cosa si tratta.

Esempio

What are you doing tonight?

(Che cosa fai questa sera?)

Si usa to do quando si parla del lavoro, degli studi, di un What do you do?

compito specifico che si svolge.

(Che lavoro fai?)

I'm doing a research on this subject.

(Sto facendo una ricerca su questo

argomento.)

I must do the ironing.

(Devo stirare.)

Si usa to do per gli sport praticati senza l’uso della palla, I do aerobics.

espressi da un sostantivo.

(Faccio/ pratico l’aerobica.)

Si usa to do nelle seguenti espressioni:

To do an exercise: fare un esercizio

To do someone a favour: fare un favore a qualcuno

To do one's best: fare del proprio meglio

Could you do me a favour?

(Potresti farmi un favore?)

You should do your best.

(Dovresti fare del tuo meglio.)

To do the shopping: fare la spesa

To do the homework: fare i compiti

I have a lot of homework to do.

(Ho molti compiti da fare.)

To do the washing up: lavare i piatti

Can you do the washing up?

(Puoi lavare i piatti?)

To do the cleaning: fare le pulizie

Si usa do/does/did come ausiliare delle forme

Do you like dancing?

interrogative e negative dei verbi non ausiliari al Simple (Ti piace ballare?)

Present, al Simple Past e all'Imperativo.

I don't like dancing.

(Non mi piace ballare)

I didn't go to the party last night.

(Non sono andato alla festa ieri sera.)

You don't speak German, do you?

(Non parli tedesco, vero?)

Lo si può usare anche in frasi affermative, in questo

caso ha lo scopo di enfatizzare ciò che si sta dicendo

Yes, I do speak German!

(Ma si, parlo tedesco!

Do usato come ausiliare in frase

affermativa rafforza ciò che si sta

dicendo.)

43

Le proposizioni concessive e avversative

Although

Althoug (benché / anche se) introduce una frase concessiva.

Maria went to school although she was ill. Maria andò a scuola anche se era malata.

Although è spesso rinforzato da still / anyway / all the same (comunque / lo stesso)

Maria still went to school, although she was ill. Maria andò a scuola lo stesso, benché fosse

malata.

Even though

Even though (sebbene / per quanto) si usa per evidenziare il contrasto

Even though she felt very ill, Maria went to school.

Sebbene / Per quanto si sentisse molto male, Maria andò a scuola.

Though

Though (‘anche se’) è meno formale di although e even though. Nel parlato e nei testi informali, la

preposizione concessiva di divide spesso in due frasi con though in fondo.

Though she was ill, Maria went to school. Anche se era malata, Maria andò a scuola.

Maria went to school. She was ill, though. Maria andò a scuola, Era malata, però.

While e whereas

While e whereas (mentre) si usano con valore avversativo, ma anche al posto di although nel

parlato formale e per iscritto.

While / Whereas some experts expect the Government to win the election, most believe that the

opposition will win.

Mentre alcuni esperti prevedono che il governo vinca le elezioni, la maggior parte ritiene che

vincerà l’opposizione.

Despite e in spite of

Despite e in spite of (nonostante / malgrado / pur + il gerundio) introducono una concessiva. Sono

sempre seguito da una costruzione nominale o dalla forma in -ing mai da un tempo verbale.

Despite / in spite of her illness, Maria went to school. Nonostante / malgrado la sua

indisposizione, Maria andò a scuola.

Despite / In spite of being ill, Maria went to school. Pur essendo indisposta, Maria andò a scuola.

Non si può dire: Despite / In spite of she felt ill, Maria went to school. (frase scorretta)

However

However (tuttavia / comunque / però) introduce o conclude una frase avversativa, edè sempre

preceduto o seguito da una virgola. E più frequente per iscritto, e nel discorso formale.

Maria was ill. Howevwer, she went to school. Maria era malata. Tuttavia andò a scuola.

Maria went to school. She was ill, however. Maria andò a scuola. Era malata, però.

44

Non si può dire: However she was ill, Maria went to school (frase scorretta).

On the other hand

On the other hand (D’altra parte, D’altro canto) introduce un punto di vista contrastante. Di solito

si usa nel discorso formale e per iscritto.

Television has many advantages. It keeps us informed about the latest news, and also provides

entertainment in the home.

On the other hand, television has been blame for the violent behaviour of some young people, and

for encouraging children sit indoors, instead taking exercise.

Present Perfect Simple

Il Present Perfect Simple è un tempo passato che generalmente in italiano si traduce con il passato

prossimo.

Il Present Perfect Simple si forma con il presente dell’ausiliare have seguito dal participio passato