Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

1

LINGUA INGLESE I

INDICE

Bibliografia

0. Parole, sintagmi, frasi

1. Parole e frequenze

2. Classi lessicali, frequenze, registri

3. Dizionari, concordanze, collocations

4. I sintagmi

5. La frase

6. Il nome

7. Il verbo

8. L’inglese contemporaneo

Schede

2004-2005

gb

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

2

Bibliografia

- COBUILD = Collins COBUILD Advanced Learner’s English Dictionary, HarperCollins 2003.

- COLLOCATIONS = Oxford Collocations Dictionary for Students of English, Oxford University Press 2002.

- D = Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway, Oxford University Press 2000.

- GRADIT = Grande Dizionario Italiano dell’Uso, ideato e diretto da Tullio De Mauro, UTET 2000

(una versione ridotta è pubblicata da Paravia, 2000).

- LGSWE = Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English, by Douglas Biber, Stig Johansson,

Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad, Edward Finegan, London, Pearson Education Limited 1999.

- LONGMAN = Longman Dictionary of Contemporary English, Longman 2003

- OED = Oxford English Dictionary, second edition, 20 vols., Oxford University Press 1989.

- P = Jane Austen, Persuasion, Penguin Books 1998.

- SGSWE = Longman Student Grammar of Spoken and Written English, by Douglas Biber, Susan Conrad,

Geoffrey Leech, Longman 2002 (a reduced version of LGSWE).

- Suzanne Romain ed., The Cambridge History of the English Language, vol. IV 1776-1997,

Cambridge University Press 1997.

- WEBSTER = Webster’s Third New International Dictionary, Springfield, Mass., Merriam-Webster 1993.

- tesi di laurea discusse all’Università di Padova (Dipartimento di Anglo-Germanico):

Marilena Poles, A Tagged Corpus of Narrative English with Sample Analyses of Lexicon and Syntax

(anno acc. 1994-1995, relatore G. Brunetti).

Arianna Scremin, A Tagged Corpus of Journalistic English with Sample Analyses of theLexicon

(anno acc. 1996-1997, relatore G. Brunetti).

Alessandra Tadiotto, A Tagged Corpus of Journalistic English with Sample Analyses of the Syntax

(anno acc. 1996-1997, relatore G. Brunetti).

0. Parole, sintagmi, frasi

0.1 Costituenti – constituents

“[…] he had reached his hotel he crossed the hall with its mounds of reddish chairs and sofas

its spike leaved withered looking plants he got his key off the hook the young lady handed

him some letters he went upstairs […]”

E’ un frammento di testo a cui è stata tolta la punteggiatura, tranne gli spazi fra le parole. Può

servire per un piccolo esperimento, cioè la verifica che un testo (o un frammento di lingua) non è

fatto di una successione indifferenziata di parole (per cui hotel viene dopo his e prima di he), ma di

gruppi di parole strutturate a vari livelli (per cui hotel sta con his e non con he). Il principale di

questi gruppi, o costituenti, è la frase (clause), intuitivamente definibile come un’unità di senso

compiuto, o meglio come una struttura predicativa che è completa se ha almeno tutti gli elementi

richiesti dal predicato (o verbo). Il verbo reached richiede chi compie l’azione e la destinazione

dell’azione stessa, e quindi con hotel termina la prima frase; handed invece richiede due

complementi (a chi si porge, him, e ciò che si porge, letters); e così di seguito:

“[…] (1) he had reached his hotel . (2) he crossed the hall with its mounds of reddish chairs

and sofas its spike leaved withered looking plants . (3) he got his key off the hook . (4) the

young lady handed him some letters . (5) he went upstairs […]”

Anche le frasi non sono fatte semplicemente di parole, ma di gruppi di parole detti sintagmi

(phrases): nella frase (1) had e reached (ausiliare e participio passato) formano il sintagma verbale

(verb phrase, VP); nella (4) lady (nome) forma con the (articolo) e young (aggettivo) un sintagma

nominale (noun phrase, NP); nella (3) off (preposizione) forma con the e hook un sintagma

preposizionale (prepositional phrase, PP). I sintagmi possono essere fatti di una sola parola (la

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

3

frase (5) ha tre sintagmi) o di combinazioni complesse di parole: nella frase (2) with (preposizione)

sta con its mounds, che a sua volta sta con of reddish chairs and sofas, e with è sottinteso anche

davanti a its…plants: un doppio PP, il primo dei quali contiene un altro PP con of. Nell’originale la

frase (3) ha questa punteggiatura:

“He crossed the hall, with its mounds of reddish chairs and sofas, its spike-leaved, witheredlooking plants.” (D 130)

Spike-leaved e withered-looking sono aggettivi composti: parole fatte di parole, così come un

sintagma può esser fatto di sintagmi, e anche avere una frase tra i suoi costituenti, come in:

“she had influenced him more than [any other person he had ever known]” (D 130)

E’ il fenomeno detto embedding: costituenti incassati (embedded) dentro altri costituenti.

In Midsummer Night’s Dream (v.i) Shakespeare fa uso comico di un’individuazione erronea dei costituenti del

testo: l’attore che introduce la rappresentazione davanti al duca di Atene ingarbuglia la punteggiatura e dice

che lui e gli altri attori vengono a dispetto e non a diletto del pubblico,

Consider then, we come but in despite.

We do not come as minding to content you,

Our true intent is. All for your delight,

We are not here. That you should here repent you,

The actors are at hand…

mentre avrebbe voluto dire il contrario:

Consider then, we come – but in despite

We do not come – as minding to content you;

Our true intent is all for your delight;

We are not here that you should here repent you.

The actors are at hand…

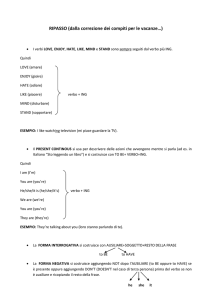

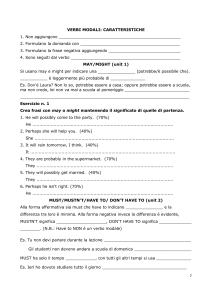

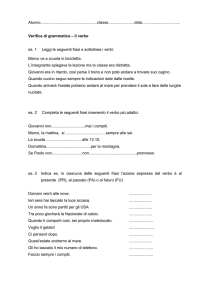

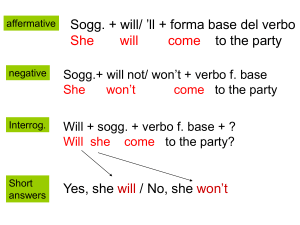

0.2 Grammatica e uso

E’ di questi costituenti che si occupa la grammatica – parole, sintagmi e frasi, words, phrases,

clauses: proprietà delle parole, tipi e struttura dei sintagmi, tipi e struttura delle frasi. La

grammatica teorica ricerca le regole generali (o universali) che presiedono alla loro formazione; la

grammatica descrittiva, invece, oltre a farne il repertorio completo per una determinata lingua, ne

documenta anche l’uso nelle diverse situazioni, o registri, di quella lingua. Una lingua infatti può

essere pensata come un insieme di risorse che sono non solo diversamente possedute dai singoli

parlanti, ma soprattutto diversamente impiegate nei vari registri: e per esempio nomi, verbi,

aggettivi e avverbi sono usati in proporzioni molto diverse nella conversazione (CONV), nella

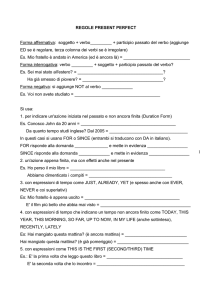

narrativa (FICT), nel giornalismo (NEWS) e nella prosa accademica (ACAD):

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

4

Figure 0.1 from SGSWE

frequency per million words

(thousands)

distribution of lexical classes

600

500

adv

400

adj

300

verbs

200

nouns

100

0

CONV

FICT

NEWS ACAD

1. Parole e frequenze

1.1 La frequenza del lessico – word frequency

“The young people could not talk,” pensa fra sé

l’anziana protagonista di Mrs Dalloway mentre

intrattiene due giovani dell’alta società che se ne

stanno muti alla sua festa; “...the enormous resources

of the English language, the power it bestows...of

communicating feelings...was not for them” (D 151).

Il lessico è una risorsa che si presenta secondo vari ordini di grandezza: un dizionario dell’uso

contemporaneo come il COBUILD del 2003 dice di contenere 110.000 parole ricavate

dall’inglese parlato e scritto degli anni ’90; il WEBSTER, dizionario dell’inglese americano,

dichiara 472.000 voci (edizione 1993), mentre l’OED del 1989 registra 550.000

parole attestate dal 1150 a oggi. Si pensa che una persona istruita conosca anche più di 50.000

parole.

number of entries in dictionaries of English

550,000

472,000

110,000

106,000

-

OED (1989)

WEBSTER (1993)

COBUILD (2003)

LONGMAN (2003)

Ma la grandezza più significativa è statistica: le parole hanno frequenze d’uso molto diverse,

e le parole di più alta frequenza costituiscono un’alta percentuale di tutto l’inglese contemporaneo

parlato e scritto.

Il COBUILD e il LONGMAN sono stati i primi dizionari (dalle edizioni del 1995) a dare

informanzioni sulla frequenza delle parole, contrassegnando tre bande di mille parole ciascuna, “the

top 3000 most frequent words.” Il LONGMAN distingue anche la frequenza tra parlato e scritto

(vedi i grafici alle voci alone, learn, remain).

Quanto frequenti sono le parole più frequenti? ovvero, conoscendo le prime mille o duemila

parole, quanto inglese si riuscirebbe a capire? Usando il programma indicato nella scheda 1 e un

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

5

corpus di inglese narrativo di circa 100.000 parole (tesi di laurea Poles: campioni da cinquanta

romanzi inglesi del periodo 1962-1993) si ottengono questi dati:

FICTION

WORD LIST

one

two

three

not in the lists

Total

TOKENS/%

83665/80.7

6297/ 6.1

1723/ 1.7

11993/11.6

103678

TYPES/%

FAMILIES

2650/22.4

1808/15.3

786/ 6.6

6577/55.6

980

895

421

?????

11821

2296

Le percentuali dei tokens (tutte le occorrenze di parole grafiche distinte, types) indicano che la prima

banda (list) copre da sola oltre l’80% del corpus. I dati possono essere confrontati con quelli di un

analogo corpus di inglese giornalistico (tesi di laurea Scremin e Tadiotto: articoli dai tre periodici

Economist, Nature e New Statesman del 1995):

NEWS

WORD LIST

TOKENS/%

one

two

three

not in the lists

71022/72.7

4698/ 4.8

7346/ 7.5

14636/15.0

Total

97702

TYPES/%

2680/22.3

1335/11.1

1506/12.5

6494/54.0

12015

FAMILIES

955

681

549

?????

2185

Il conteggio congiunto dei due corpus dà le percentuali indicative di quanto inglese scritto

contemporaneo è costituito da parole delle tre bande di frequenza più alta, singolarmente e

cumulativamente:

FICTION + NEWS

WORD LIST

TOKENS/%

TYPES/%

one

two

three

not in the lists

154687/76.8

10995/ 5.5

9069/ 4.5

26629/13.2

3225/16.9

2248/11.8

1669/ 8.8

11908/62.5

Total

201380

19050

FAMILIES

992

944

558

?????

2494

Campioni più estesi – di milioni di parole – confermano questi dati: le duemila parole più frequenti

coprono più o meno l’80% dell’inglese contemporaneo parlato e scritto.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

6

tokens, types, lexemes

Con ‘parola’ (word) si intendono varie unità di un testo: tutte le parole grafiche (forme lessicali, word-forms, o

tokens) di cui è fatto, che sono le ripetizioni di un certo numero di parole grafiche distinte (tipi, types), a loro volta

forme flesse di un certo numero di nomi, verbi, aggettivi…(lessemi, lexemes).

“Sir William was no longer young. He had worked very hard; he had won his position by sheer ability (being the son

of a shop-keeper)” (D 81): è fatto di 25 token, 23 type [he e had ricorrono due volte] e 22 lessemi [1 nome proprio

(William), 5 nomi comuni (sir, position, ability, son, shop-keeper), 4 verbi (be, have, work, win), 2 aggettivi (young,

sheer), 3 avverbi (long, very, hard), 1 pronome (he), 4 determinanti (no, his, the, a), 2 preposizioni (by, of)].

Ricondurre le forme lessicali di un testo ai lessemi si dice lemmatizzazione (i ‘lemmi’ sono le voci di un dizionario).

1.2 La difficoltà lessicale

Le bande possono essere usate per misurare la difficoltà lessicale dei testi, e quindi la competenza

richiesta per la loro comprensione. La difficoltà varia da testo a testo, ma varia anche per tipi di

testi, o registri, come mostra il confronto tra FICTION e NEWS.

La scheda 1 spiega come si può ottenere una misura della difficoltà lessicale di Mrs Dalloway e

confrontarla con quella di Persuasion.

1.3 Un confronto con l’italiano

Secondo il GRADIT l’italiano contemporaneo, parlato e scritto, è prodotto con anche maggior

economia: 90% è costituito da 2.049 vocaboli ‘fondamentali’ (FO), un ulteriore 6% da altri 2.576 di

‘alto uso’ (AU); vengono poi 1.897 vocaboli di ‘alta disponibilità’ (AD), 47.060 vocaboli ‘comuni’

(CO) e così via. Il GRADIT registra 250.000 lemmi.

1.4 Fantalinguistica

Se mai potesse esistere una lingua in cui tutte le parole sono equiprobabili (cioè di uguale

frequenza), bisognerebbe conoscerle tutte per capire anche solo la frase più semplice: chi

conoscesse, per es., solo 2.000 parole di una lingua di 100.000, capirebbe mediamente solo il 2% di

quella lingua.

Il forte divario di frequenza fra le parole è perciò un principio di economia ed efficacia

comunicativa.

1.5 Come misurare il proprio lessico

Un campione indicativo è la verifica sul 2% del lessico di un dizionario: se ha 1000 o 1500 o 2000

pagine, se ne prendono 20 o 30 o 40 da varie lettere dell’alfabeto, si contano le parole conosciute e

si moltiplica per 50. Per l’inglese si suggeriscono le pagine con parole comincianti per C-, EX-, J-,

O-, PL-, SC-, TO-, UN-. Il conteggio può essere raffinato distinguendo fra lessico passivo (parole

che si conoscono ma non si usano) e lessico attivo (parole che si usano); all’interno del lessico

passivo si può anche distinguere tra ‘bene’ e ‘vagamente’, e all’interno di quello attivo tra ‘spesso’ e

‘occasionalmente’. Il lessico passivo dovrebbe risultare maggiore di quello attivo.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

7

2. Classi lessicali, frequenze, registri

2.1 Distribuzione delle classi lessicali

La differenza tra FICTION e NEWS non è solo di difficoltà lessicale: è anche di distribuzione delle

classi lessicali (o parti del discorso):

Figure 2.1 distribution of word classes (tokens%)

25

20

15

FICTION

NEWS

10

5

0

n

v

adj

adv

pn

p

pr

c

d

nu

i

n=nomi; v=verbi; adj=aggettivi; adv=avverbi; pn=nomi propri; p=pronomi; pr=preposizioni;

c=congiunzioni; d= determinanti; nu=numerali; i=interiezioni

Le prime quattro classi, le più importanti, hanno profili caratteristici: le NEWS – con più nomi e

aggettivi, meno verbi e avverbi – hanno uno stile nominale.

Figure 2.2 distribution of word classes (tokens%)

25

20

15

FICTION

10

NEWS

5

0

n

v

adj

adv

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

8

2.2 Registri – registers

Le risorse linguistiche sono impiegate diversamente nelle varie situazioni d’uso, o registri. LGSWE

ne distingue quattro principali nell’inglese contemporaneo:

CONV = conversation

FICT = fiction (= narrativa d’invenzione, per es. romanzi)

NEWS = newspapers

ACAD = academic prose (= testi scientifici, critici, storici...);

e, attingendo al suo corpus di 40 milioni di parole, mostra come essi si distinguano per vari

parametri, uno dei quali è la diversa frequenza d’uso delle classi lessicali. NEWS è quello che

impiega più nomi, CONV quello che ne usa di meno, mentre usa più verbi; ACAD usa più aggettivi

degli altri:

Figure 2.3 from SGSWE

frequency per million words

(thousands)

distribution of lexical classes

600

500

adv

400

adj

300

verbs

200

nouns

100

0

CONV

FICT

NEWS ACAD

corpus linguistics

corpus

A corpus is a large collection of written or spoken texts that is used for language research (COBUILD)

L’ultima generazione di dizionari e grammatiche inglesi è basata su spogli di corpus, che documentano l’uso effettivo

di parole e strutture, con relative frequenze d’uso. Lo spoglio tipico è quello della concordanza, che riporta tutti i

contesti in cui ricorre una data parola, consentendo così di ricavarne significati e regole d’uso. Alcuni corpora:

- The Bank of English (520 milioni di parole): è alla base del COBUILD 2003;

- The British National Corpus (100 milioni di parole): è usato dai dizionari della Oxford University Press;

- The Longman Spoken and Written English Corpus (40 milioni di parole): è alla base della LGSWE e della SGSWE,

una grammatica che oltre a descrivere le strutture riporta anche le relative frequenze per registri.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

9

3. Dizionari, concordanze, collocations

you shall know a word by the company it keeps (J.R. Firth)

3.1 Concordanze

Come ha diversi ordini di grandezza, così il lessico ha anche varie forme di rappresentazione.

Quella del dizionario è la forma elenco, compatta e di veloce consultazione: nel COBUILD e nel

LONGMAN la parola ‘damage’ viene dopo ‘dam’ e prima di ‘damask’. Nell’uso però ‘damage’

tiene compagnia ad altre parole, con le quali fa grammatica e senso. La forma di rappresentazione

che ci mostra il contesto d’uso di una parola è la concordanza; ecco quella che vi dà il corpus del

COBUILD:

me but they caused an awful lot of damage [p] Beadle reckons he's still going

companies -- but caused only minor damage. A third bomb was defused by

[/h] [p] A TEACHER whose voice was damaged after years of shouting in the

is done nearby, resulting in damage and even death to the trees.

Jackson's lawyers are seeking huge damages and an unreserved apology from the

ligaments and he may have cartilage damage as well. David is in plaster

[p] The sheer size of the damages award against BDO Binder Hamlyn

unequivocally. Football is further damaged by his Chinese whispers. [p] [h]

such as the Uffizi in Florence (damaged by a terrorist bomb attack three

be magically lowered without the damaging deflationary effects of cuts in

Attacks Sexual Abuse [f] and the damage done to their developing psyches by

and the inevitable disruption would damage education. They claimed that

raiders, who cut through a fence, damaged eight other vehicles as they

top of the Young Rider tree. Some damaging falls then undermined her

be resting in the boot of the rust-damaged Ford Cortina parked half on the

is claiming £ 30 million damages from Scottish Secretary Michael

forces in command at Daru that this damage had been inflicted by the rebels as

not play again this season, thus damaging his chances of playing a part in

but they could cause a lot of damage in trying to do so. The authorities

is responsible for the environmental damage inflicted on the Niger Delta over

storage for six weeks or more, the damage is done. [p] The bales in the stack

and is being cleaned before the damage is assessed. A number of companies

Osijek, is among the most heavily damaged regions. According to the Croatian

mineral or vegetable oil-based can damage rubber. If in doubt consult your

production of the acids which can damage teeth. After sugary food or drinks

at half-past-eight. It extensively damaged the ground floor and part of the

look older without actually damaging the canvas as well?" she asked

from loss destruction of or damage to property at each separate

abuses in the Empire, irreparable damage to African cultures, traditional

says he will donate appropriate damages to charity. [p] [h] MONEY BLOODY

form of parental behaviour causes damage to the developing child whose

to make false claims for hurricane damage to houses she does not own. [p]

a sexual motive. [p] There was no damage to the house and we don't yet know

[p] And the final bill covering damage to roads and rivers in Grampian

in the Gulf, because of the terrible damage war will do to the environment. [p]

businesses at Lloyd's and those damages were chargeable to income tax in

One can only wonder what long-term damage you have inflicted on these

E’ un piccolo campione, ma basta per dare una certezza e un sospetto: la prima è che ‘damage’ è

verbo e nome, e che il verbo ha oggetto diretto; il secondo è che il nome ha sì singolare e plurale ma

che tra i due ci sia una differenza semantica. Nel senso di ‘danno’ inferto o patito ‘damage’ è solo

singolare, mentre al plurale ha solo il senso giuridico di ‘danni’ chiesti o accordati in tribunale. E’

su uno spoglio simile che si redige la relativa voce del dizionario. E lo spoglio dà anche

informazione sui compagni di ‘damage’, i suoi collocates (co-occorrenze)…

La scheda 2 dà un esempio di concordanza da Persuasion.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

10

3.2 Co-occorrenze – collocates

Le parole con cui co-ricorre più frequentemente:

‘damage’ (verbo) predilige avverbi come ‘badly, severely, seriously, extensively, permanently’;

‘damage’ (nome sing.) va con verbi come ‘cause, inflict, do, suffer’, e l’aggettivo ‘severe’;

‘damages’ (nome pl.) s’accompagna ai verbi ‘award, claim, sue for, seek, pay, win’.

Questa informazione fraseologica è dispersa nelle pagine del dizionario, come si può verificare

consultando le voci ‘claim, sue, badly, severely’; ed è recuperabile in blocco attraverso la ricerca

full text su CD: la ricerca full text dà tutti gli esempi in cui una data parola compare nel dizionario –

è cioè un tipo di concordanza.

Esistono anche dizionari di collocates, come COLLOCATIONS della Oxford.

Le parole non vanno pensate come oggetti inerti da inserire in strutture grammaticali preesistenti,

ma come oggetti portatori di strutture (regole d’uso) e preferenze combinatorie (collocates): le

prime sono vincolanti (‘damage’ verbo ha l’oggetto diretto, ‘damage’ nome non ha plurale nel senso

di ‘danno subito o causato’…), le seconde sono facoltative e un parlante può scegliere tra

l’idiomaticità e l’innovazione.

3.3 Reticoli di parole

E seguendo la traccia dei collocates si intravvede una terza forma di rappresentazione del lessico: il

reticolo associativo, di cui le parole sono nodi (‘nodes’). Per es. ‘damages’ porta al verbo ‘sue for’,

che co-occorre anche con ‘libel’ (‘diffamazione’), e al verbo ‘award’, che co-occorre anche con

‘prize’ e ‘medal’; e se si sceglie il nodo ‘badly’ si trovano le combinazioni ‘badly damaged, badly

hurt, badly injured…’:

injured

injuries

casualties

managed

badly

inflict

suffer

damage

sue for

award

damaged

damages

libel

prize

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

11

4. I sintagmi

4.1 Classi lessicali e sintagmi – word classes and phrases

In inglese una parola può appartenere a più classi lessicali (o parti del discorso, parts of speech),

come nella tabella seguente:

Table 4.1 word classes

word

N

1

before

V

Adj

Adv

*

Prep

Conj

examples

I’ve never seen her before

*

she arrived before noon

*

before you leave, let me know

2

early

*

I’ll catch an early train

*

I have to get up early

3

narrow

*

here the track narrows

*

we went through the narrow streets

4

round

*

there will be another round of talks

*

the ship rounded Cape Horn

*

there is a round table in the room

*

she turned round

*

the car turned round the corner

5

like

*

we shall not seen his like again

*

I like your new hair-style

*

they are of like mind

*

you are behaving like an idiot

*

like I said, I don’t read much

N = noun, V = verb, Adj = adjective, Adv = adverb, Prep = preposition, Conj = conjunction

Le classi principali formano 5 tipi di sintagmi (phrases):

sintagma nominale

sintagma verbale

sintagma aggettivale

sintagma avverbiale

sintagma preposizionale

NP

VP

AdjP

AdvP

PP

noun phrase (ex. a strong government)

verb phrase (ex. she arrived)

adjective phrase (ex. unbearably dull)

adverb phrase (ex. too rashly)

prepositional phrase (ex. in the old town)

La parola base del sintagma – quella che ne determina il tipo – è detta testa (head).

4.2 NP

La struttura generale dell’NP è:

determiner + premodifier(s) + N + postmodifier(s)

a | happy | mother | with a healthy baby

det pre

N

post

Determiner sono articoli, dimostrativi, possessivi..., e anche ’s-genitive:

a book || my books || those books || some books || Jane’s books

Premodifier(s) sono uno o più aggettivi, o nomi in funzione aggettivale:

the new English books || a second-class ticket

Postmodifier(s) sono PP o frasi o avverbi:

the books on the shelf || the books I have bought on the Internet || the day before

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

12

L’NP è il sintagma che ha la struttura più variabile in complessità: va da 1 a un numero

teoricamente illimitato di parole, vi entrano quasi tutte le parti del discorso, è fatto di altri sintagmi e

anche di frasi. Questo sintagma nominale da Mrs Dalloway ha una testa postmodificata da un PP a

sua volta postmodificato da una frase (clause) che contiene un NP postmodificato da una frase che

contiene un PP postmodificato da una frase:

the horror of the moment when someone told her at a concert that he had married a woman met on

the boat going to India (D 7)

[NP the horror [PP of the moment [CLAUSE when someone told her at a concert that he had married [NP

a woman [CLAUSE met [PP on the boat [CLAUSE going to India]]]]]]] (D 7).

Pre e postmodificazione variano a seconda dei registri. LGSWE mostra che sono scarse in CONV e

aumentano progressivamente da FICT a NEWS ad ACAD (NEWS ha il più alto tasso di entrambe):

Figure 4.2 pre- and postmodification of NP (from LGSWE)

noun phrases per million words

(thousands)

distribution of noun phrases with premodifiers

and postmodifiers

350

300

250

both

200

post

150

pre

100

none

50

0

CONV

FICT

NEWS

ACAD

4.3 VP

Il VP è fatto di verbi in un ordine fisso – un verbo lessicale preceduto da 1, 2 o 3 ausiliari:

modal + have + be + V

she arrived

she has arrived || the parcel was dispatched

she should have arrived || the agreement is being signed

she must have been delayed.

Eventuali avverbi intercalati non fanno parte del VP:

she has just arrived ha 3 sintagmi, NP (she) VP (has...arrived) AdvP (just).

Il sintagma verbale è finito (finite) se il verbo è al presente, al passato o al futuro; non finito (nonfinite) se il verbo è all’infinito o al participio:

we don’t know what to do || I like drinking || I’ll have the bike repaired

NOTA: il sintagma verbale è qui inteso come in grammatica descrittiva; in grammatica teorica,

invece, per sintagma verbale s’intende il predicato, cioè il verbo con i suoi complementi:

[NP the boy][VP left the house], dove VP = V + NP.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

13

4.4 AdjP

Nell’AdjP l’aggettivo può essere pre-modificato da un avverbio e post-modificato da un PP o una

frase:

premodifier + Adj + postmodifier

very | good | at her work

pre

Adj

post

extraordinarily ugly || desperately poor

guilty of a serious crime || slow to respond || particularly good at singing

4.5 AdvP

L’avverbio testa dell’AdvP può avere pre- e post-modificazione:

premodifier + Adv + postmodifier

much more quickly || independently of each other

4.6 PP

Il PP è formato da preposizione più complemento, che di solito è un NP; può avere un avverbio

premodificatore:

premodifier + preposition + complement

in the early morning || across the street || like a baby || soon after the war

Il complemento può essere anche una frase finita o non finita:

about what had happened

without saying a word

Il PP eredita la complessità dell’NP. Nella frase seguente (da Time, October 15, 2001) sia il PP

iniziale che l’NP finale sono postmodificati da una frase (clause):

[PP despite the modernization [CLAUSE that took place after the discovery of oil reserves in 1938]],

Saudi Arabia remains [NP a land [CLAUSE where rigid religious and traditional values are strictly

enforced]].

4.7 Scomposizione della frase (clause) in sintagmi (phrases)

I sintagmi sono i costituenti della frase,

my friend | has arrived | by train

NP

VP

PP

ed ogni frase si scompone in sintagmi. Per farlo, prima si individua il verbo,

I met Clarissa in the Park this morning

e poi si prova a fare spostamenti per verificare quali parole formano sintagmi indipendenti:

this morning I met Clarissa in the Park || in the Park I met Clarissa this morning

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

14

I sintagmi possono essere individuati anche come risposte a domande:

who did you meet in the Park this morning? Clarissa

where did you meet Clarissa this morning? in the Park

when did you meet Clarissa in the Park? this morning

Quindi (trattando pronomi e nomi propri come nomi):

[NP I ] [VP met ] [NP Clarissa ][PP in the Park ][NP this morning]

Nella frase seguente ci sono 2 sintagmi dopo il verbo:

most Swedes consider him reliable him most Swedes consider reliable

how do most Swedes consider him? reliable

who do most Swedes consider reliable? him

[NP most Swedes][VP consider ][NP him ][AdjP reliable]

In quest’altra, invece, le parole dopo il verbo formano un unico sintagma complesso,

Streseman was the youngest child of a lower middle-class family in Berlin

dove la testa child è pre-modificata da youngest e post-modificata da of a lower middle-class family

in Berlin

[NP the [AdjP youngest] child [PP of a lower middle-class family in Berlin]]

E il PP può a sua volta scomporsi in

[PP of [NP a [AdjP lower middle-class ] family [PP in Berlin]]]

Un unico NP con post-modificazione viene prima del verbo anche in quest’altra frase:

the risks of a prolonged physical disruption seem small

[NP the risks of a prolonged physical disruption][VP seem][AdjP small]

[NP the risks [PP of a prolonged physical disruption]]…

Mentre nella successiva i sintagmi prima del verbo sono 2:

for generations the Martinez family had bred heavily-built horses

the Martinez family had bred heavily-built horses for generations

[PP for generations][NP the Martinez family][VP had bred][NP heavily-built horses]

La scheda 3 contiene classi lessicali e sintagmi da identificare, e frasi da scomporre in sintagmi.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

15

5. La frase

5.1 Elementi della frase e loro realizzazioni – clause elements and their realizations

Le frasi 1 e 2 si scompongono negli stessi sintagmi (NP VP NP),

1 she married an astronaut

2 she became an astronaut

Lo stesso per le frasi 3 e 4 (NP VP NP NP),

3 they sent John a present

4 they elected John chairperson

Ma i sintagmi realizzano elementi sintattici e semantici diversi.

La frase si struttura attorno al verbo, che specifica il processo di cui si tratta (attività fisica o

mentale, stato…) e il numero e la natura dei partecipanti coinvolti: marry ha due partecipanti

(umani), become uno solo. Tutti e due i verbi richiedono, insieme al soggetto, un complemento, che

nel caso di marry denota un partecipante distinto dal soggetto, nel caso di become una

qualificazione del soggetto stesso. In termini sintattici (S = soggetto, V = verbo):

marry S V Od (oggetto diretto, direct object)

become S V Ps (predicativo del soggetto, subject predicative).

Per le frasi 3 e 4:

send

S V Oi Od (oggetto indiretto, indirect object; oggetto diretto, direct object)

elect

S V Od Po (oggetto diretto, direct object; predicativo dell’oggetto, object

predicative).

Gli elementi sintattici sono così realizzati nella frase 2:

S

V

Ps

she | became | an astronaut

NP

VP

NP

Si dice che il verbo become ha valenza 2, o che è un verbo a due posti, cioè richiede un soggetto e

un predicativo del soggetto – quest’ultimo realizzato anche da un sintagma aggettivale:

S

V

Ps

she | became | angry

NP

VP

AdjP

Anche marry ha valenza 2, ma richiede soggetto e oggetto diretto (marry può essere usato anche

con valenza 1, ma come verbo reciproco: they married). Send e elect hanno valenza 3.

I predicativi Ps e Po possono essere anche realizzati da PP:

they elected a woman as president

E oltre a Od e Oi c’è anche l’oggetto preposizionale, Op, prepositional object:

the surgeon operated on the patient

Table 5.1 clause elements and their phrase realizations

element

NP

VP

AdjP

x

S, subject

x

V, verb

x

Od, direct object

x

Oi, indirect object

Op, prepositional object

x

x

Ps, subject predicative

x

x

Po, object predicative

PP

x

x

x

La scheda 4 (1) contiene frasi da analizzare in elementi e loro realizzazioni.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

16

5.2 Valenza del verbo – verb valency

Oggetti (Od, Oi, Op) e predicativi (Ps, Po) sono anche chiamati collettivamente complementi

(complements): il loro numero e la loro natura dipendono dalla valenza (valency) di V – a 1, 2 o 3

posti:

one-place verbs hanno il soggetto e nessun complemento;

two-place verbs hanno il soggetto e un complemento;

three-place verbs hanno il soggetto e due complementi.

Un verbo può avere più valenze:

Table 3.2 one-, two-, three-place verbs

verb

1 place

2 places

1 grow

SV

SVN

S V Adj

2 open

SV

SVN

3 rely

S V on N

3 places

S V on N for N

4

become

5

consider

SVN

S V Adj

SVN

SVNN

S V N Adj

6

elect

SVN

SVNN

S V N as N

examples

the roses are growing

my neighbours grow roses

he’s growing old

the door opened

she opened the door

we cannot rely on her

we can rely on her for advice

she became a footballer

the wind is becoming stronger

we are considering your proposal

I consider you my best friend

everybody considers her clever

they elected the new president

they elected Johnson president

they elected a woman as president

5.3 Elementi realizzati da frasi - elements and their clause realizations

Soggetto e complementi (S; Od, Oi, Op; Ps, Po) sono realizzati sia da sintagmi che da frasi

dipendenti finite o non finite (finite or non-finite clauses):

S

V

Ps

standing here all day | is | very tiring

non-finite clause

VP AdjP

S

V

Od

the girl | admitted | the mistake

NP

VP

NP

S

V

Od

she | admitted | that a mistake had been made

NP

VP

finite clause

S

V

Od

We | don’t know | what she’s going to do

NP VP

finite clause

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

17

S V

Oi

Od

we | told | her | to stay with us

NP VP NP

non-finite clause

S

V

Od

they | want | you to say the truth

NP

VP non-finite clause

Notare la differenza di analisi fra le ultime due frasi:

tell ha valenza 3 (we told her that) (what did you tell her? to stay with us) [her è Oi di told]

want ha valenza 2 (they want that) (what do they want? you to say the truth) [you è S di to say]

5.3.1 Verbi a controllo – control verbs

Le due frasi seguenti hanno gli stessi elementi (S V Oi Od), realizzati dagli stessi sintagmi:

1 she | told | me | to come

2 she | promised | me | to come

ma in 1. Oi fa anche da soggetto sottinteso di to come; in 2. è S che fa anche da soggetto sottinteso

di to come. Tell e promise sono detti ‘verbi a controllo’, perché controllano il soggetto della frase

dipendente non finita da essi retta:

tell è un object-control verb (l’oggetto di tell è anche il soggetto della dipendente non finita);

promise è un subject-control verb (il soggetto di promise è anche il soggetto della dipendente non

finita).

Nella scheda 4 (2) ci sono verbi i cui soggetti o complementi sono realizzati da frasi.

5.4 Gli avverbiali – adverbials

Oltre a soggetto, verbo e complementi, la frase può avere anche uno o più avverbiali (A,

adverbials), che specificando le circostanze dell’azione – quando, dove, come, perché. Sono

realizzati da NP, AdvP, PP e frasi dipendenti finite e non finite, e occupano varie posizioni nella

frase:

he’s coming next week

yesterday I met her at the station

we enjoyed the film immensely

she has kindly lent me her own car

we stayed at home because of the bad weather

grumbling, she left the room

her father died when she was young

we didn’t mention the subject so as not to hurt her

5.5 Elementi e loro realizzazioni - elements and their realizations

Complessivamente gli elementi sintattici della frase sono

S + V + complements, adverbials

Tranne il verbo, che è sempre un VP, gli altri elementi possono essere realizzati da sintagmi e frasi

dipendenti (finite e non finite):

S

V

Od

Jane and I | enjoyed | seeing you

NP

VP

non-finite clause

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

18

A

S

V

Od

angered by the decision,| she | wrote | a letter of complaint

non-finite clause

NP VP

NP

S

V

Ps

whether he wins or not | remains | to be seen

finite clause

VP

non-finite clause

S

V

Od

we | suggest | that you apologize for being late

NP VP

finite clause

____|__________________________

S

V

Op

that | you | apologize | for being late

conj NP

VP

non-finite clause

Table 5.3 clause elements and their phrase or clause realizations

element

NP VP

AdjP AdvP PP

finite clause

x

x

S, subject

x

V, verb

x

x

Od, direct object

x

x

Oi, indirect object

x

x

Op, prepositional object

x

x

x

x

Ps, subject predicative

x

x

x

x

Po, object predicative

x

x

x

x

A, adverbial

non-finite clause

x

x

x

x

x

x

5.6 Embedding

Le frasi sono fatte di sintagmi, che sono fatti di parole: ma questa gerarchia può essere capovolta e

un sintagma contenere un altro sintagma (un PP postmodifier in un NP o in un AdjP) o anche una

frase (anch’essa postmodifier in un NP o in un AdjP); e una frase può avere altre frasi dipendenti,

finite e non finite, come realizzazioni dei suoi elementi (soggetto, complementi, avverbiali). Si

chiama embedding questo fenomeno di strutture incassate in strutture dello stesso livello o di livello

inferiore.

Embedding di frasi in sintagmi e in frasi:

who is the man sitting next to you?

you should be ready to act promptly

we talked about going to the seaside

she went out as I came in

having arrived late, I went straight to bed

what he is looking for is a wife

to be a writer is her greatest ambition

I think that you are wrong

I tried to talk to her

I gave whoever it was a ten-pound note

it depends on what they decide

she insists on being present

the hope is that things will improve

his pastime is playing practical jokes

you can call me whatever you like

we found him overcome with grief

postmodifier of NP

postmodifier of AdjP

complement of PP

A

A

S

S

Od

Od

Oi

Op

Op

Ps

Ps

Po

Po

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

19

5.7 Extraposition

Nell’esempio seguente, che elemento è realizzato dalla frase embedded?

1a it was true that the family was of German origin (D 105)

Riformulando l’intera frase in questo modo

1b that the family was of German origin was true (D 105)

si vede che la frase embedded realizza il soggetto, e che in 1a. è stata spostata in fondo

(‘extraposed’) lasciando il posto al pronome it. Quest’ultimo è solo un segna-posto (è detto infatti

‘espletivo’, cioè ridondante: expletive, anticipatory or dummy it) e fa da soggetto insieme alla frase

in extraposition:

S V

Ps

S

it | was | true | that the family was of German origin

NP VP AdjP finite clause

L’extraposition si può avere anche con una frase non finita,

it was silly to have other reasons for doing things (D 9)

e la frase embedded può realizzare anche l’oggetto diretto:

she found it impossible to write a letter to ‘The Times’ (D 153).

5.8 Frasi dipendenti finite – finite dependent clauses

Frasi dipendenti finite sono le relative, le nominali, le avverbiali e le comparative.

5.8.1 Frasi relative – relative clauses

Restrittive o non restrittive, sono tipicamente parte di NP:

she is the only person who can help us

Mr Hopkins, who is 78, lives alone

he is a man of considerable wealth, which he spends on charity

5.8.2 Frasi nominali – nominal clauses

Sono introdotte da that, what, why, whether, how..., e realizzano il soggetto, l’oggetto diretto e il

predicativo del soggetto:

I’ll do whatever you want

what we need is a strong coffee

I was asked whether I wanted to stay at a hotel or at his home

he knew that the attempt was useless

she inquired how Jack was getting on

I would like to know why you are so late

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

20

5.8.3 Frasi avverbiali – adverbial clauses

Sono introdotte da subordinatori come when, as, if, because, until, while, though..., e realizzano

avverbiali di circostanza:

the performance was cancelled because the leading actor was ill

it was very late when she returned

if you do that for me I will be pleased

though he has lived for years in London he still writes in German

5.8.4 Frasi comparative – comparative clauses

Sono introdotte dai subordinatori than e as:

I was more unhappy than I’ve ever been since (D 36)

it was later than she thought (D 117)

he looks older than he is

it is not as simple as it looks

5.9 Frasi non finite – non-finite clauses

Sono di tre tipi: infinitive clauses, ing-clauses, ed-clauses.

5.9.1 Infinitive clauses (with or without to)

I hate to see such behaviour

the old man is afraid to go into hospital

she won’t let you go

we hear her sing all day

to be successful you must never give up

5.9.2 ing-clauses

she shook her head, smiling

the bus carrying the supporters was stopped by the police

we cannot rely on her being here on time

5.9.3 ed-clauses

you are advised to follow the procedure approved by the committee

painted white, the house looks bigger

La scheda 5 contiene frasi da analizzare in elementi e loro realizzazioni.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

21

6. Il nome

6.1 Genere – gender

A father and his son were driving to a ball game when their car stalled on the railroad tracks. In the distance a train

whistled a warning. Frantically, the father tried to start the engine, but in his panic he couldn’t turn the key, and the car

was hit by the train. An ambulance picked them up, but on the way to the hospital the father died. The son was still

alive but his condition was very serious, and he was carried into an emergency operating room. The surgeon came in,

expecting a routine case. However, on seeing the boy, the surgeon blanched and muttered, ‘I can’t operate on this boy

– he’s my son’.

I nomi inglesi hanno genere naturale: sono maschili (masculine) o femminili (feminine) se si

riferiscono esclusivamente a uomini (father, son, boy...) o donne (mother, aunt, girl...); sono neutri

(neuter) se non si riferiscono a nessuno dei due (train, car, engine...), e duali (dual) se possono

riferirsi a entrambi (surgeon, friend, journalist, writer, reader...). Il genere grammaticale è limitato

ai pronomi personali di terza singolare (he, she, it; his, himself…).

I nomi neutri possono essere personificati al femminile o maschile: ship è she nel cap. 8 di

Persuasion.

Per specificare il genere, nel caso di un nome duale, si ricorre al pronome (“The surgeon came

in... she blanched and muttered...”), oppure a un premodifier o a un composto: a male nurse, a

female officer, a policewoman. Il duale è utile quando il genere è irrilevante o si vuole evitare di

specificarlo: chairperson invece di chairman, firefighter invece di fireman. Ma che pronome segue

un duale inclusivo? L’inglese, come l’italiano, ha il maschile come genere non marcato (unmarked,

che include cioè anche l’altro genere):

1 “A translator of a classical text is not merely taking things from one language and putting them

into another. He is also taking things from one time and adapting them to another. He not only

translates but modernizes as well” (R. Scholes and R. Kellogg, The Nature of Narrative, Oxford

University Press 1966, p. 283).

Quest’uso verrebbe oggi giudicato sexist. Un uso invece politically correct è oggi il seguente:

2a “Often a student asks what is the point of learning high school mathematics. This book tries

to show that these mathematical skills let him or her probe entirely new fields of thought such as the

theory of relativity” (E. A. Robinson, Einstein’s Relativity in Metaphor and Mathematics,

Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, Prentice Hall 1990, p. xiii);

2b “The learner can set his or her existing knowledge in the context of a more general

observation, can also, perhaps, extend his or her vocabulary in the area of ‘talking about topics’, and

perhaps can choose the most suitable word for the idea s/he wishes to express at this time” (Susan

Hunston and Gill Francis, Pattern Grammar, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, John Benjamins 2000, p.

263).

Quest’uso è diventato quasi obbligato nel registro ACAD; ma ripetere, come nell’esempio 2b, tre

volte la coppia di pronomi in tre righe successive sa di goffaggine.

Una scelta alternativa, comune nel parlato, è they come ‘singolare generico’, cioè non sex-specific:

3a “This certificate lists the four courses for which the student was registered, showing letter

grade assessments of their work over the year for their examination performance” (from a 1990

document of the University of London). Quest’uso ha anche autorevoli precedenti letterari:

3b Jane Austen: “she felt that were any young person...to apply to her for counsel, they would

never receive any of such certain immediate wretchedness” (P 26-7); “Every body has their taste in

noises as well in other matters” (P 121: per altri esempi in Jane Austen cfr.

http://www.pemberley.com/janeinfo/);

3c Virginia Wolf: “Everyone gives up something when they marry” (D 56); “Everyone if they

were honest would say the same” (D 68).

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

22

Degli esempi seguenti, il 4a evita il problema e il 4b (dallo stesso libro) ricorre alla scelta

innovativa del femminile come genere non marcato (simmetricamente all’esempio 1):

4a “What about the contemporary programmer or engineer who merely wants to use

cryptography? Where does that person turn?” (Bruce Schneier, Applied Cryptography, New York,

Wiley 1996, p. xvi).

4b “Suppose a sender wants to send a message to a receiver. Moreover, this sender wants to send

the message securely: She wants to make sure an eavesdropper cannot read the message” (Bruce

Schneier cit., p. 1). Stessa scelta del femminile non marcato c’è in questo libro di filosofia (sulla

teoria dei mondi possibili):

4c “If a philosopher thinks that her serious explanatory purposes are not served by Possible

Worlds,…then she is bound…to abstain from its use,” John Divers, Possible Worlds, London and

New York, Routledge 2002, p. 17)

“There is in Korean mythology a famous measuring unit that denotes a very long period of time...

One is asked to imagine a mountain, made of solid granite, exactly one mile high. Once every

thousand years an angel flies down from heaven and brushes the summit of the hill with her wings.

The unit of time represents the number of years it would take for the angel and her summit-brushing

wing to erode the mountain down to sea level. Given long enough, of course, she would do it,”

S. Winchester, The Map that Changed the World. William Smith and the Birth of Modern Geology, New York,

HarperCollins 2001, p. 69.

Non c’è una soluzione buona per tutti i casi: è raccomandabile l’uso di forme variate, evitando la

stolida ripetizione della stessa formula (“If every person who called themself a linguist settled down

to provide a full description of a single previously undescribed language, then he or she would

justify the title,” R.M.W. Dixon, Ergativity, Cambridge UP 1994, p. 229).

marcato/non marcato – marked/unmarked

Quando ci sono coppie oppositive uno dei due termini assume anche significato generico:

high/low: the wall is two feet high… the building is 30 stories high

long/short: three millimetres long… 120 metres long

wide/narrow: two inches wide… 10 kilometres wide

E la relativa proprietà è designata con il termine non marcato: height, length, width.

old/young: ‘how old is she?’ ‘she is a young girl – she is only 12 years old’

La distinzione marcato/non marcato si applica anche ai fenomeni sintattici, come l’ordine delle parole, o elementi

della frase, in particolare i complementi. Quelli delle seguenti frasi

Od S V…: Hugh she detested for some reason (D 62)

Po S V Od: cold, heartless, a prude, he called her (D 7)

sono detti ordini marcati, rispetto ai normali – cioè non marcati – S V Od e S V Od Po. L’ordine marcato serve a

mettere in rilievo un elemento, o a creare qualche particolare enfasi.

6.1.1 Nota storica

L’inglese ha introdotto il genere naturale nel periodo del Middle English (1100-1500); nel periodo

precedente dell’Old English sunne ‘sun’ era femminile, mona ‘moon’ maschile, wif ‘female’ neutro

e wif-mann ‘woman’ maschile. La rinuncia al genere grammaticale è correlata alla caduta della

declinazione dell’aggettivo e all’introduzione dell’articolo indeclinabile the: tra nome, articolo e

aggettivo non c’è più bisogno di accordo di genere e numero (gender and number agreement).

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

23

6.1.2 Politically correct

Nel 1990 il sindaco di Los Angeles ha messo al bando ogni forma di sexist language nei documenti

comunali, decretando l’uso di chairperson invece di chairman, humanity invece di mankind,

maintenance holes invece di manholes.

L’uso di un lessico non discriminatorio e non offensivo è un’esigenza molto sentita nell’inglese

contemporaneo. La pulizia delle città, un tempo fatta da refuse/garbage collectors è oggi affidata a

disposal operatives (GB) e sanitation engineers (USA). Negli Stati Uniti il primo termine della

serie seguente ha rimpiazzato tutti quelli che lo seguono:

African-American Afro-American negro coloured black

Da una vignetta di Jules Pfeiffer (1965):

“I used to think I was poor. Then they told me I wasn’t poor, I was needy. They told me it was self-defeating to think

of myself as needy, I was deprived. Then they told me underprivileged was overused. I was disadvantaged. I still don’t

have a dime. But I have a great vocabulary.”

6.2 Numero – number: countable and uncountable

Al contrario del genere, la determinazione del numero (singolare/plurale) non è sempre naturale.

Tree, year, idea sono nomi countable, cioè considerati come riferentisi a entità numerabili, e

hanno singolare e plurale (trees, years, ideas).

Furniture, information, advice sono invece uncountable, e hanno solo il singolare.

Alcuni nomi sono sia COUNT che UNCOUNT: difficulty, war, fear.

to protest against injustice; the injustices of world poverty.

I nomi di sostanza che sono UNCOUNT quando indicano la sostanza (beer is made from fermented

malt) e COUNT quando indicano un suo tipo (we have quite a good range of beers) o una sua

quantità (would you like a beer? = a glass of beer).

6.2.1 Countability and reference

Un NP può avere riferimento generico o specifico:

1a cats are domestic animals

1b the cats in our house are all Persians

2a English is a Germanic language

2b the English of Jane Austen is very elegant

generic reference

specific reference

generic reference

specific reference

L’uso degli articoli definito e indefinito dipende da countability e reference:

Table 6.1 countability and reference

uncountable

countable

sing

sing

pl

a/an, the

generic

the

the

the

specific

the kangaroo lives in Australia (count/generic) o anche: kangaroos live in Australia

wine is made from grapes (uncount/generic)

Altri esempi di nomi UNCOUNT con riferimento generico:

beer is Britain’s favourite Friday night drink

fear conscripts its own armies, takes its own prisoners (Time, October 22, 2001)

human nature may be great in times of trial (P 139)

Altri esempi di nomi COUNT con riferimento generico:

a doctor must use caution, anche doctors must use caution

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

24

officials were vague about the target but precise about the timing (Time, October 22, 2001)

ex-military officers are teaching reporters and aid workers how to survive the perils of war

(Time, October 22, 2001)

La scheda 6 riguarda countability e reference.

6.3 Caso – case

Il genitivo, o s-genitive, è una sopravvivenza dei casi flessivi dell’Old English:

Charles’s grandfather

the two girls’ mother

last week’s Observer

Il genitivo può essere usato come determiner o pre-modifier di un NP, e come soggetto di una

frase non finita in -ing.

6.3.1 The determiner s-genitive

Specifica il riferimento dell’NP in cui ricorre (‘di chi è’):

Mrs Smith’s eldest daughter = the eldest daughter of Mrs Smith

my youngest child’s computer = the computer of my youngest child

this season’s games = the games during this season

today’s lower standards = the lower standards that apply today

Ha la stessa funzione di un determinante (a/an, the, his/her, that/this...): occupa infatti la posizione

iniziale dell’NP che lo contiene e non può essere usato insieme a un altro determinante dell’NP; e i

pre-modifier dell’NP principale vanno inseriti dopo il genitivo. Essendo esso stesso un NP può

avere il suo determinante e i suoi pre-modifier:

it was the brilliant young general’s most spectacular victory

it was [NP [Det the brilliant young general’s ][Pre most spectacular ][Head victory ]]

…[Det [Det the ][Pre brilliant ][Pre young][Head general’s ]]…

Può essere anche usato da solo con NP principale sottinteso,

Jane’s car is faster than Jim’s

o come predicativo:

this car is Jane’s (= this is Jane’s car)

6.3.2 The pre-modifier s-genitive

Indica ‘di che tipo è’:

a boys’ school = a school for boys

a men’s team = a team for men

a warm summer’s day = a warm day in summer

a woman dressed in a man’s raincoat = ...in a raincoat for men

the oldest women’s club = the oldest club for women

[NP [Det the][Pre oldest ][Pre women’s ][Head club ]]

6.3.3 The subject s-genitive

Nell’esempio seguente

I object to John’s staying here

la frase embedded (complemento di un PP che realizza un Op) ha il genitivo come soggetto:

I object [Op/PP to [CLAUSE [S John’s ][V staying ][A here ]]]

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

25

6.3.4 Distribuzione

Non tutti i nomi compaiono al genitivo, e i registri ne fanno uso molto diversificato. La tabella di

LGSWE (p. 299) mostra che i più frequenti sono i nomi di persona (propri e comuni), seguiti dai

collettivi e dai nomi di luogo; e che NEWS è il registro con la maggiore densità,

corrispondentemente al suo alto tasso di nomi:

Table 6.2 density of genitive nouns

CONV

FICT

NEWS

personal

collective

place

time

other

each represents c. 500 occurrences per million words, fewer than 250

ACAD

La scheda 7 chiede di identificare i tre usi di s-genitive.

6.4 Word formation

Nomi, verbi, aggettivi e avverbi sono classi lessicali aperte (open classes), che si possono cioè

accrescere; mentre preposizioni, congiunzioni, pronomi, determinanti e ausiliari sono classi chiuse

(closed classes). Quelle delle classi aperte sono dette anche ‘parole lessicali’ (lexical words), e

quelle delle classi chiuse ‘parole funzionali’ (function words).

Oltre all’introduzione di parole completamente nuove, ogni lingua ha regole per formare parole

nuove da parole esistenti – parole della stessa classe o di altra classe:

Adj Adj: wise unwise

Adj Adv: wise wisely

Adj V: modern modernize

Adj N: modern modernity

L’inglese ha tre regole di formazione:

1. affissazione – affixation

2. composti – compounds

3. conversione – conversion

Affissi sono prefissi e suffissi (prefixes and suffixes):

friend friendly, unfriendly, unfriendliness, friendless, friendlessness, friendship

agree agreement

proportion disproportionately

known unknown

understanding misunderstanding

suppose supposition

terror terrorism, terrorist

equal equality

conscious consciousness

Composti:

landslide, highway, spokeswoman

Conversione (detta anche ‘affissazione zero’, zero affixation):

walk, talk, drink, attempt, desire (verbi e nomi)

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

26

Persuasion ha:

reason (nome e verbo), reasonable, reasonably, unreasonable, unreasonably, unreasonableness

wretched, wretchedly, wretchedness

persuade, persuadable, unpersuadable; persuasion, overpersuasion

romance (nome e verbo), romantic

una ricca scelta di suffissazioni in -ness:

nothingness, littlenesses, singleness, sameness, coldness, undesirableness, fearlessness,

hopelessness, solitariness ecc.

e tra i composti si segnalano quelli in -looking:

ill-, well-, good-, best-, fine-, odd-, deplorable-looking

LGSWE (p. 322) dà i seguenti dati per i suffissi più comuni nella formazione di nomi astratti:

Table 6.3 frequency of suffixes used to form abstract nouns

CONV

FICT

NEWS

ACAD

-tion

-ity

-ism

-ness

each represents c. 500 occurrences per million words, fewer than 250

Persuasion conferma la prevalenza di -ness in FICT.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

27

7. Il verbo

7.1 Classe azionale – Aktionsart

1a we walked for an hour

abbiamo camminato/passeggiato per un’ora

1b we walked to the station abbiamo raggiunto la stazione a piedi

L’italiano non può tradurre le due frasi con lo stesso verbo perché evidentemente

camminare/passeggiare indicano solo un’attività che dura nel tempo, non un’attività che si

conclude con il raggiungimento di una meta. Il verbo inglese, invece, può indicare entrambe le cose:

può alternare tra due diverse ‘classi azionali’.

I verbi designano ciò che è (o sussiste) e ciò che accade. E fra gli accadimenti si distinguono quelli

‘atelici’ (che non hanno un punto terminale intrinseco, tipo talk) e quelli ‘telici’ (che ce l’hanno,

tipo build); e fra i telici si distingue ulteriormente tra quelli che hanno una durata (tipo build) e

quelli che sono istantanei (tipo explode). Ne risulta una quadripartizione di ‘classi azionali’

(Aktionsart, ‘forma d’azione’: è parola tedesca):

States: be tall, love, know, have, believe

Activities: march, walk, swim, think, rain, read, eat, sing, dance, talk, cry, sleep

Accomplishments: melt, freeze, dry, learn, build

Achievements: pop, explode, collapse, shatter, break

I tratti distintivi sono 3: stativo o dinamico (±static); telico o atelico (±telic); con o senza durata

(±punctual):

Table 7.1 Aktionsart features

static

States

+

Activities

Accomplishments

Achievements

-

telic

+

+

punctual

+

Ci sono test per stabilire a quale classe appartiene un verbo:

Table 7.2 Aktionsart tests

verb occurs with

1

progressive

2

adverbs like actively, vigorously

3

adverbs like quickly, slowly

4

phrases like for an hour

5

phrases like in an hour

States

No

No

No

Yes

No

Activities

Yes

Yes

Yes

Yes

No

Accomplishments

Yes

No

Yes

irrelevant

Yes

Achievements

No

No

No

No

No

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

28

7.2 Alternanza di classe azionale

Un verbo appartiene a una classe base (read, walk e swim sono activities), ma può alternare di

classe a seconda della costruzione in cui ricorre. L’alternanza più comune è tra activities e

accomplishments:

activities

2a she read the book for an hour

3a he walked in the park for ten minutes

4a he swam in the river

accomplishments

2b she read the book in an hour

3b he walked to the park in ten minutes

4b he swam the river with his clothes on

Questa alternanza non c’è in tutte le lingue: in italiano c’è per i verbi transitivi in genere; e tra gli

intransitivi c’è per correre (e per volare e saltare), ma non per altri verbi di tipo di moto come

camminare, marciare, viaggiare, nuotare (4b è attraversò il fiume a nuoto…). In inglese è invece

generalizzata:

5a she hurried across the courtyard attraversò in fretta il cortile

5b the soldiers marched back to the barracks i soldati tornarono in caserma marciando

Traducendo, siamo costretti a usare un verbo telico (che indichi compimento dell’azione), lasciando

il tipo di moto o implicito

6a we walked out of the shop

siamo usciti dal negozio

6b she walked me to the front gate mi accompagnò al cancello

o specificato in qualche maniera:

7a I am planning to drive to Morocco next year …andare in macchina…

7b she drove Anna to London …portare in macchina…

In queste costruzioni sono presenti tre componenti di significato: moto, tipo di moto e meta.

L’inglese combina le prime due nel verbo, mentre altre lingue danno loro espressione separata.

Table 7.3 Accomplishments with verbs of manner of motion

1.a

andò

in macchina

alla stazione

2.a

andò

a piedi

alla stazione

*

2.b

1.b

VERB

motion

PHRASE

manner

VERB

she walked

she drove

PHRASE

goal

PHRASE

Romance and Slavic languages

Germanic languages

to the station

to the station

NOTA: I verbi italiani che, come correre, hanno alternanza di classe azionale, la marcano con

diverso ausiliare:

8a ho il fiato grosso perché ho corso

8b appena ho saputo sono subito corso a casa

[activity]

[accomplishment]

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

29

7.3 Alternanze di valenza: l’ambitransitività – ambitransitivity

Nell’esempio seguente il verbo retire è usato prima come transitivo (verbo con oggetto diretto), poi

come intransitivo (verbo senza oggetto):

“Creel shut down the Midpac’s headquarters in St. Jude, fired or retired a third of its employees,

and moved the rest to Little Rock. Alfred retired two months before his sixty-fifth birthday.”

(J. Franzen, The Corrections, London, Fourth Estate 2002 (2001), p. 80)

Soggetto di retire può essere sia dell’impiegato (Alfred) che ‘va in pensione’ che la ditta o il

dirigente (Creel) che lo ‘mette in pensione’. I verbi inglesi sono in maggioranza sia transitivi che

intransitivi – sono ambitransitivi.

E l’ambitransitività è di due specie:

Si=St: il soggetto intransitivo corrisponde a quello transitivo

he’s eating spaghetti he’s eating

Si=Ot: il soggetto intransitivo corrisponde all’oggetto transitivo

the boy broke the window the window broke

Su ‘transitivo’ e ‘intransitivo’ (e ‘inaccusativo’) vedi la scheda 8.

7.4.1 Ambitransitività Si=St

Un tipo di ambitransitività Si=St avviene per omissione dell’oggetto diretto

Sean decided he wanted to write, and quit his job (LONGMAN)

Due sottoclassi importanti di ambitransitivi Si=St sono i verbi che sottintendono un oggetto

riflessivo

Joel dressed / washed (bathe, change, shave, shower, strip, undress)

o un oggetto reciproco

they touched / married (court, cross, date, divorce, embrace, kiss, meet, quarrel)

7.4.2 Ambitransitività Si=St : verbi reciproci – reciprocal verbs

Do people in Britain kiss when they meet?

Alcuni verbi possono presentare un processo reciproco fra due partecipanti sia come S V O

(O=Od/Op) che come S V:

that’s where I met my wife

that’s where my wife and I met

she kissed him

they kissed

I quarrelled with my friend

my friend and I quarrelled

Così anche agree, argue, collaborate, consult, date, divorce, embrace, exchange, fight, marry, meet,

part, separate, share, struggle, touch...

Altri verbi hanno invece bisogno del pronome per esprimere reciprocità:

when we were young we loved passionately

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

30

significa che ciascuno era innamorato di una persona diversa; altrimenti si dovrebbe dire ...we loved

each other passionately. Così anche we know each other; they ask each other questions; we don’t

see much of each other these days.

7.4.2 Ambitransitività Si=St : Od Op

Un altro tipo di ambitransitività Si=St avviene per alternanza tra oggetto diretto e oggetto

preposizionale:

she shot him she shot at him [= he was hit he may have been missed]

he swam the river he swam across the river

they fled the building they fled from the building

they roamed the woods they roamed in the woods [= fuller coverage less full]

she met the Dean she met with the Dean [= perhaps by chance arranged]

England will be playing France England will be playing against France

Le coppie non sono sempre sinonime, come è indicato tra parentesi quadre. Nelle due frasi seguenti

si implica, rispettivamente, simmetria e asimmetria:

firefighters battled the flames for four hours last night (LONGMAN)

she had battled bravely against cancer (LONGMAN)

7.5 Ambitransitività Si=Ot

Lo stesso partecipante è soggetto nella forma intransitiva e oggetto in quella transitiva:

the door opened

the window broke

the water is boiling

her resolve weakened

she burned the house

the car is moving

the price of oil increased

the engine is still running

somebody opened the door

the boy broke the window

we are boiling the water

the news weakened her resolve

the house is burning

he was told to move his car

they have increased the price by 50%

run the engine for a moment

Esempi da Mrs Dalloway:

1a Clarissa’s eyes filled with tears (D 149) ‘…si riempirono…’

1b tears filled his eyes (D 18)

‘…gli riempirono gli occhi…’

2a boys in uniform…marched (D 43)

‘…marciavano…’

2b she had marched him up and down (D 159) ‘…l’aveva fatto marciare…’

3 that project for emigrating young people (D 92) ‘…far emigrare giovani…’

Nella frase 3 emigrating, verbo intransitivo (più eventuale avverbiale …to Canada), è

parafrasabile come making young people emigrate (o causing young people to emigrate), la stessa

parafrasi applicabile alla frase 2b (she had made him march).

La scheda 9 mette a confronto l’ambitransitività Si=Ot in inglese e in italiano.

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

31

7.5.1 Child English: disappear

E’ noto che i bambini di lingua inglese tendono a trattare disappear come un verbo Si=Ot :

I disappeared it (= I made it disappear)

E’ una spia della facilità con cui i verbi inglesi cambiano di transitività.

7.5.2 Ambitransitività multipla: consult

you should consult your doctor

he needed to consult with an attorney

the umpires consulted quickly

[Od]

[Op]

[reciproco]

Non tutti i dizionari però riportano un altro uso intransitivo di consult il cui il soggetto non è chi

‘consulta un esperto’ ma l’esperto che ‘dà consulti o consulenza’ (Si=Ot), come in

dr Stevens consults daily from nine to eleven

La scheda 10 è su transitività e ambitransitività.

7.6 Verbi passivi – passive verbs

Attivo e passivo sono modi alternativi di formulare l’azione dando la posizione di soggetto ai vari

partecipanti. Possono essere passivizzati i verbi con oggetto (Od, Oi, Op).

7.6.1 Finite passives

[S the police ][V are questioning ][Od the suspects ]

[S the suspects ][V are being questioned ][Op by the police]

[S he ][V told ][Oi her ][Od the whole story ]

[S she ][V was told ][Od the whole story ][Op by him ]

[S the whole story ][V was told ][Oi to her ][Op by him ]

[S the committee ][V will look ][Op into the matter ]

[S the matter ][V will be looked into ][Op by the committee ]

[S they ][V appointed ][Od her ][Po chairperson ]

[S she ][V was appointed ][Ps chairperson ][Op by them ]

7.6.2 Non-finite passives

Il passivo compare anche in costruzioni non finite come postmodifier di un NP o di un AdjP

let us look at an example given by the LONGMAN dictionary

the foreign guests had the honour of being received by the Prince of Wales

any decisions are likely to be taken

e come complemento di un VP

we had all the locks changed

greenhouse gases continue to be emitted in large quantities

7.6.3 Verbi che non hanno il passivo

Non tutti i verbi con oggetto hanno la voce passiva:

- she lacks confidence, the skirt does not fit you, he resembles his father sono solo attivi;

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

32

- arrive at, go into, look into sono passivi solo con soggetto astratto – cioè se usati metaforicamente:

the problem was carefully gone into/looked into

an unexpected result was arrived at

- solo oggetti realizzati da frasi finite possono essere soggetti passivi:

Whether former feelings were to be renewed, must be brought to the proof (P 57)

7.6.4 Usi del passivo

a. dare prominenza a un partecipante piuttosto che a un altro:

the boy was diagnosed as autistic

this bed was slept in by Queen Elizabeth

b. omettere un partecipante perché irrilevante o indeterminato o sconosciuto (short passive):

he was murdered in mysterious circumstances

c. omettere il soggetto in una frase subordinata o coordinata:

she doesn’t want to be arrested by the police

she felt ill and was taken to hospital

d. dislocare a fine frase come Op-agente un soggetto attivo complesso (long passive):

the news was brought by a woman who happened to be present at the moment of the accident

Il passivo è più frequente nella prosa accademica e nel giornalismo. Ecco due esempi NEWS di

long passive con Op-agente complesso:

“A mythical landscape of snow-covered fantasy, Lapland is inhabited by Santa Claus and his team

of

industrious elves creating colourful gadgets for the world’s children. Finland, the country on whose

peninsula the real Lapland perches, is actually inhabited by Nokia and a constellation of inventive,

mobile technology companies developing the next generation of colourful gadgets for the world’s

grown-ups.” (The Guardian Weekly, October 26 to November 1 2000)

La scheda 11 chiede di trasformare i passivi in attivi identificando i loro oggetti.

La scheda 12 chiede di trasformare gli attivi in passivi.

7.7 Promozione a soggetto – promotion to subject

Il passivo è un modo di promuovere a soggetto partecipanti normalmente oggetti (in qualche caso

anche avverbiali). Una promozione analoga si ha anche con certi verbi attivi:

1 clothes iron better when damp

2 these cars sell quickly

3 that wine drinks well

4 Shakespeare translates well into Greek

5 John broke a leg in the race

6 the guitar broke a string mid-song

7 these ingredients will bake 4 cakes

8 this table seats twelve

9 this caravan sleeps four

In 1-4 è l’oggetto che è stato promosso a soggetto; in 5-6 è il possessivo; in 7 è l’avverbiale

strumentale; e in 8-9 è l’avverbiale locativo. E in 9 sleep è transitivo!

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

33

7.8 Stranded prepositions

Trasformandosi in soggetto del passivo, l’oggetto preposizionale lascia la preposizione appesa dopo

il verbo (la si può ritenere parte del VP):

this patient | cannot be operated on

they | cannot operate | on this patient

the matter | will be dealt with | immediately we | will deal | with the matter | immediately

In termini di sintagmi, il PP (= prep + NP) viene separato nei suoi costituenti e l’NP dislocato a

realizzare S.

E’ invece dislocata la preposizione nelle frasi relative:

the man about whom we are talking...

the man whom we are talking about...

the man_ we are talking about...

E nelle frasi interrogative con who, which, what, where, how:

which house did you live in as a young girl?

where do you come from?

Persuasion è ricco di stranded prepositions dei vari tipi:

1 A house was never taken good care of...without a lady (P 21)

2 ...which she grieved to think of (P 24)

3 “What part of Bath do you think they will settle in?” (P 38)

4 ...which Anne perfectly knew the meaning of (P 78)

5 She had nothing else to stay for (P 84)

6 They were people whom her heart turned to very naturally (P 145)

7 “You must tell me the name of the young lady I am going to talk about. That young lady, you

know, that we have all been so concerned with. The Miss Musgrove, that all this has been

happening to...” (P 152)

8 ...a “good morning to you”, being all that she had time for (P 158)

9 He is the most agreeable man she ever was in company with (P 158)

10 A moment’s reflection shewed her the mistake she had been under (P 172)

11 Nothing of the sort you are thinking of will be settled any week (P 173)

12 “And has it indeed been spoken of?” (P 174)

13 “...which I objected to” (P 178)

14 “The letter I am looking for...” (P 179)

15 “But Mr. Elliot was not yet done with” (P 183)

Lingua Inglese I 2004-2005 gb

34

7.9 Verb + particle(s)

Il significato del verbo può essere integrato o modificato da una particella avverbiale o

preposizionale, o da tutt’e due insieme:

1 things are looking up (= improving)

phrasal verb

2 look that word up in the dictionary (= find)

phrasal verb

3 we will look into the matter (= examine)

prepositional verb

4 she looks down on everybody (= regards with superiority) phrasal-prepositional verb

In 1 il verbo ha valenza uno e la particella è un avverbio;

in 2 il verbo ha valenza due con Od e la particella è un avverbio (Od anche dopo: look up that

word...);

in 3 il verbo ha valenza due con Op e la particella è una preposizione;

in 4 il verbo ha valenza due con Op e le particelle sono un avverbio e una preposizione.

La distinzione sintattica importante è fra 2 e 3: avverbio e Od oppure preposizione e Op.