caricato da

common.user16395

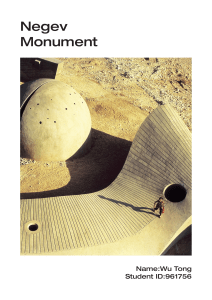

Monuments and Site-Specific Sculpture in Urban and Rural Space