Bronchiolite

Bronchiolite

L’incidenza annuale è di 11.4% nei bambini sotto 1

anno e 6% tra 1-2 anni. La malattia è responsabile di

4500 decessi e 90,000 ricoveri ogni anno negli USA.

Tra i bambini di 2 anni circa il 95% ha evidenza

sierologica di una pregressa infezione con il virus

respiratorio sinciziale. Rara nel neonato (< 28 gg) x

Ab. materni

Fattori di rischio:

Età < 6 mesi

Bambini con cardiopatia congenita

Bambini con displasia broncopolmonare

Bronchiolite

La B. è una infiammazione acuta delle piccole vie respiratorie che

esita in broncocostrizione per:

mediatori della flogosi (leucotrieni)

aumentata secrezione di muco

distruzione delle cellule epiteliali

edema delle vie aeree

È una malattia tipicamente del lattante (primi 12 mesi di vita) e

tipicamente di origine virale:

Virus respiratorio sinciziale

Virus parainfluenzale

Virus influenzale

Adenovirus

Metapneumovirus

C. trachomatis (< 4 mesi)

Bronchiolitis

Contagiosity

The disease is highly contagious. Viral

shedding in nasal secretions continues for 6

to as long as 21 days after the development of

symptoms. Incubation period is from 2-5 days.

Secondary infections occur in 46% of family

members, 98% of other children in day care,

42% of hospital staff and 45% of previously

uninfected hospitalized infants. Infection is

spread by fomites via environmental surfaces.

Hand washing and the use of disposable

gloves and gowns may reduce nosocomial

spread.

Decorso (5-7 giorni)

E’ una patologia tipica dei mesi invernali. Tipicamente

inizia come un banale raffreddore con o senza febbre di

solito di live entità e tosse. Gradualmente progredisce

verso una dispnea espiratoria con:

Tachipnea + tachicardia

Alitamento pinne nasali

Rientramenti soprasternali, intercostali e all’epigastrio

Difficoltà all’alimentazione

Complicanze:

Disidratazione

Apnee (bambini < 6 settimane)

Insufficienza respiratoria

Diagnosi

Dispnea

Wheezing (fischi e sibili su tutto l’ambito

polmonare + prolungamento della fase

espiratoria)

Rantoli fini crepitanti diffusi

Therapy

The mainstays of therapy for patients with bronchiolitis are:

oxygen supplementation and fluid replacement.

Hypoxemia

is the most common laboratory abnormality

detected, and supplemental oxygen administration is

common.

These infants are mildly dehydrated because of decreased

fluid intake and increased fluid losses from fever and

tachypnea. The goal of fluid therapy is to replace deficits and

provide maintenance requirements. Excessive fluid

requirements should be avoided as this may promote

interstitial edema formation.

Corticosteroids

Bronchodilators (?)

Indications for pediatric intensive care

referral

desaturation (Sat.O2 < 90-92%) in 40% O2 (3-

4 l/min O2)

PaCO2 > 60-65 mmHg

pH < 7.25

cyanosis

apnea

acidosis

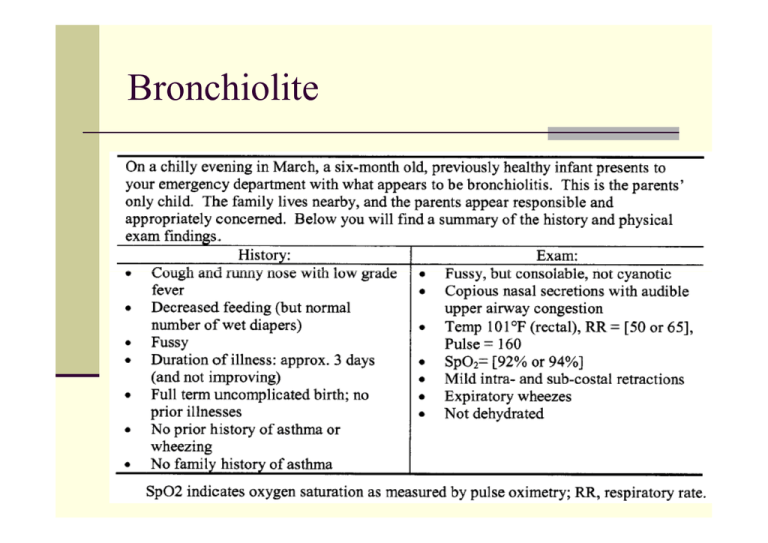

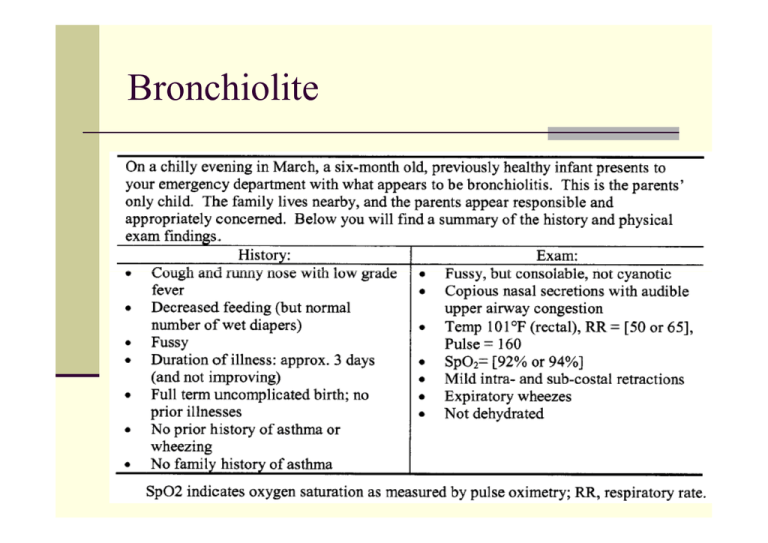

Caso clinico

A 16-month-old girl is evaluated in the ED for

increased work of breathing. She had been

seen 4 days ago for rhinorrhea, cough,

vomiting, diarrhea, and fever, all of which

appeared to have resolved. At that time, she

had a normal CBC and serum electrolyte

measurement and was treated with

intravenous fluids and discharged. Two days

later, she again developed cough with

posttussive vomiting and rhinorrhea, but no

fever or diarrhea.

Caso clinico

On physical examination, the girl is awake and alert

but in mild-to-moderate respiratory distress. Her

respiratory rate is 50 breaths/min, pulse oximetry

saturation is 94%, and heart rate is 161 beats/min.

She is afebrile. She has moderate pharyngeal

erythema, clear rhinorrhea, and a hyperemic right

tympanic membrane. Intercostal retractions, mild

wheezing, and occasional scattered crackles are

present. The rest of her physical findings are normal.

She is given three treatments of albuterol and

prednisolone and responds with a lower respiratory

rate of 40 breaths/min but a pulse oximetry saturation

of 92% in room air.

Caso clinico

She is given three treatments of albuterol and

prednisolone and responds with a lower

respiratory rate of 40 breaths/min but a pulse

oximetry saturation of 92% in room air.

Caso clinico

Initial laboratory studies include negative results for

respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) and influenza A and

B antigens. A chest radiograph shows no acute

disease and mild hyperinflation. She is admitted to

the hospital.

Over the next 3 days, she develops a temperature to

101°F (38.4°C) and has no improvement, despite

frequent albuterol treatments. On day 4, her WBC is

9x103/mcL (9x109/L), with 41% neutrophils, 2%

bands, 43% lymphocytes, and 7% monocytes, and

her platelet count is 775x103/mcL (775x109/L). A

urine culture is negative, but a blood culture is

reported positive for gram-negative diplococci.

Bronchiolite?

The patient's age of 16 months in conjunction with

cough, rhinorrhea, wheezing, and chest wall

retractions were consistent with a diagnosis of

bronchiolitis. Bronchiolitis is predominantly a viral

illness (RSV, parainfluenza 3 virus, adenovirus,

influenza virus) but also can be caused by

Mycoplasma. Notwithstanding negative antigen tests

for RSV and influenza A and B, she was treated for

presumptive viral lower respiratory tract disease.

The blood culture grew Moraxella catarrhalis, and

she was treated for 7 days with parenteral ceftriaxone

followed by 7 days of oral cefuroxime axetil. She was

discharged without complications.

Qualcosa di diverso?

Typically, bronchiolitis reaches its most critical

stage during the first 48 to 72 hours after the

onset of cough.

This patient's course was atypical because she

developed her initial fever after 3 days of cough

and wheezing, which proved to be indicative of a

bacterial infection. Although uncommon,

bronchiolitis may be complicated by bacterial

infection (about 2% to 10% of cases). Bacterial

otitis media and pulmonary bacterial coinfection,

as well as associated urinary tract infection, are

examples from recent literature.

Sepsi?

In general, a clinician should suspect sepsis

whenever a patient has fever associated with

behavioral changes such as irritability, fussiness,

lethargy, poor feeding, and altered mental status.

Tachycardia and tachypnea also may reflect sepsis.

Petechiae and purpura are well-known cutaneous

indicators of possible sepsis, especially

meningococcemia. A weak cry and jaundice may

indicate sepsis in neonates. The presentation of

sepsis depends on the competency of the patient's

immune system. Subtle presentations can occur in

young infants and immunocompromised children,

with the clinical picture influenced by the patient's

level of immunity.

Moraxella catarrhalis

M catarrhalis is an aerobic, gram-negative

diplococcus in the family Neisseriaceae that

commonly inhabits the upper respiratory tract

(nasopharynx), with increased seasonal colonization

in fall and winter. M catarrhalis can cause acute,

localized infection such as otitis media, sinusitis,

conjunctivitis, and pneumonia in children. Although it

causes a large proportion of cases of lower

respiratory tract infection in elderly patients who have

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and chronic

bronchitis, this association has not been seen in

pediatric patients.

Moraxella catarrhalis

M catarrhalis generally is not thought of as causing

invasive, systemic disease (such as meningitis and

endocarditis) except in immunocompromised

conditions.

Risk factors for bacteremia include viral infection,

sickle cell disease, malignancy, acquired

immunodeficiency syndrome, and other

immunodeficient states.

This child did not have any other evidence of

immunodeficiency; thus, additional evaluation for that

state was not undertaken. It is possible that her

hyperemic tympanic membrane was caused by an M

catarrhalis infection, but the finding also could result

from underlying viral infection.

Moraxella catarrhalis

This child did not have any other evidence of

immunodeficiency; thus, additional evaluation

for that state was not undertaken. It is

possible that her hyperemic tympanic

membrane was caused by an M catarrhalis

infection, but the finding also could result from

underlying viral infection.

Moraxella catarrhalis

In the clinical laboratory, isolates of M catarrhalis

must be differentiated from Neisseria sp. The

management and infection control differences

between Neisseria sp and M catarrhalis are

important. As in this case, identification of gramnegative diplococci in a patient's blood culture

warrants droplet precautions for suspected

meningococcemia for 24 hours while the patient

receives appropriate antimicrobial therapy.

Confirmation of N meningitidis also warrants

antimicrobial prophylaxis for appropriate

contacts.

Moraxella catarrhalis

Also, major management and social implications are

associated with the differentiation between N

gonorrhoeae and M catarrhalis when gram-negative

diplococci are identified in the smear of an eye

discharge from a baby who has neonatal

conjunctivitis. Gonococcal neonatal conjunctivitis

requires systemic antimicrobial therapy for the baby

as well as evaluation and management of the mother

and her partner. A final diagnosis of M catarrhalis

does not raise any of these issues.

Terapia

More than 85% of M catarrhalis isolates are

ampicillin-resistant because of betalactamase production. First-line antibiotics for

focal infections (otitis media, sinusitis,

pneumonia) are oral amoxicillin-clavulanate or

oral second- and third-generation

cephalosporins. Other antibiotics active

against this organism include macrolides,

trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and

fluoroquinolones.

Terapia

Sepsis generally is treated parenterally until the

patient becomes asymptomatic and has a negative

repeat blood culture, when treatment may be

changed to oral therapy to complete a 7- to 14-day

course, depending on the organism. When receiving

an initial report of "gram-negative diplococci" growing

in a blood culture, it is prudent to administer

parenteral third-generation cephalosporins (to cover

Neisseria sp and M catarrhalis) until the isolate is

identified. Then, therapy can be individualized,

depending on the clinical course and antimicrobial

susceptibility results

Messaggio da portare a casa

When the course of a patient's illness does not

follow the usual expectations, it is appropriate

to consider the possibility of multiple diseases

occurring simultaneously. Although rare, M

catarrhalis has the potential to cause a serious

bacterial infection.

The identification of gram-negative diplococcus

in the blood of a patient who has fever and

respiratory disease or otitis media should alert

the physician to the possibility of the uncommon

M catarrhalis as well as the more dangerous N

meningitidis.

Un caso “strano” per finire

Faith, 4 mesi di vita, prematura, viene

trasferita dal un Ospedale romano per febbre

(MAX: 39.6°C) da 1 settimana e diarrea.

E.O.:

modica dispnea

Tosse secca

FR 60 atti/min, Sat.O2: 90-93%

Milza e fegato palpabili a 2 cm dall’arco

costale.

Un caso “strano”

Laboratorio:

GB: 35.470 (73%)

Hb: 7.9 g/dL Trasfusa dopo 2 gg

PLT: 335.000

PCR: 18.8 mg/dL

D-dimeri: 3500 ng/mL (< 280)

EGA: modica alcalosi

Feci: Rotavirus ++

Rx torace: refertato nella norma

Inizia terapia con Amplital + Gentalyn

Un caso “strano”

Peggioramento progressivo delle condizioni generali in particolare della

dispnea.

Si sospetta bronchiolite ed inizia terapia specifica.

Dopo 4 gg di terapia:

GB: 21000 (N: 76%)

PLT: 139.000

PCR: 18 mg/dL

ECG e ecocardio: normali

Dopo 3 giorni si ripete RX torace che mostra micronoduli diffusi in tutto

il parenchima polmonare bilateralmente

TC polmonare:

Micronoduli diffusi

Focolai broncopneumonici lobo inf. Polmone dx e lingula polmone

sin.

Slargamento profilo mediastinico per incremento volumetrico timo e

linfonodi

Un caso “strano”

Peggioramento progressivo delle condizioni generali,

della dispnea, della Sat.O2, FR 85 atti/min, FC 152

atti/min.

Febbre persistente fino a 40°C, nonostante terapia

con Merrem e Targosid.

Sottopopolazioni linfocitarie:

CD4 totali (T Helper): 786.7 mmc

CD4/CD8: 2.95 (1.5-2.9)

Mantoux: neg.

Trasferimento In Unità Terapia Intensiva

HIV: Positivo

BAL: Micobatterio tubercolosi

Un caso “strano” per finire

Sepsis

Bacteremia: the recovery of bacteria in blood culture.

When bacteria are not effectively cleared by host

defense mechanisms, a systemic inflammatory

response is set into motion and can progress

independently of the original infection.

Sepsis: The systemic response to infection with

bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa or rickettsiae.

Sepsis is one of the causes of systemic inflammatory

response syndrome (SIRS). If not recognised or

treated early sepsis can progress to severe sepsis,

septic shock, multiple organ dysfunction syndrome

(MODS) and death.

Sepsis

Infection

Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome (SIRS)

•Hyper-hypothermia

•Tachycardia

•Tachypnea

•Increased or decreased white blood count

Sepsis

SIRS + hypotension

Severe Sepsis

Sepsis with organ dysfunction, hypoperfusion or hypotension,

Change in mental status, oliguria, hypoxemia, lactic acidosis

Septic shock

Severe sepsis + persistent hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation

Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome (MODS)

Homeostasis cannot be maintained without intervention

Death