Casi clinici

A “progressive” visual loss

Lorenzo Capaldi, Stefano Ursella, Luca Miele*, Dora Larussa**, Federico Pallavicini**,

Giovanni Gasbarrini*, Antonio Grieco*, Nicolò Gentiloni Silveri

An unusual cause of acute-onset and progressively worsening visual loss is presented. A 60-yearold woman was referred for left homonymous hemianopsia to our Emergency Medicine Department

because of a suspected vascular accident. Ten years earlier she had been diagnosed as having chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Brain computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed “bilateral foci of white matter abnormalities in the occipital regions, compatible with a diagnosis of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy”. Her cerebrospinal fluid was positive for

papovavirus JC. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy due to papovavirus JC, a typical

complication in AIDS patients, is a rare complication in patients with other immunosuppressive

conditions, such as chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

(Ann Ital Med Int 2004; 19: 118-121)

Key words: AIDS; Cerebrospinal fluid; Chronic lymphocytic leukemia; Papovavirus JC; Progressive

multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Introduction

maintenance therapy with interferon-α injections 3 times

weekly.

On examination she was alert and collaborative, was not

feverish, was fully conscious, had no dizziness or systemic

symptoms and her heart rate and arterial pressure were normal. Physical examination of the heart, thorax and

abdomen was unremarkable and the carotid pulses were

present with no bruits. No neck stiffness was elicited.

The patient was unsteady on her feet but there was no postural drift of the upper and lower limbs; the tendon reflexes were symmetrical and normal and the plantar reflex was

flexor bilaterally. The pupils were equal and reactive with

no ptosis. The extraocular movements were intact, without nystagmus.

The hematocrit was 0.43, the white cell count was 85

u 109/L with 0.82 lymphocytes (CD4 2.75 u 109/L; CD8

3.53 u 109/L; CD4/CD8 ratio 0.78) and 0.11 neutrophils;

her hemoglobin level was 143 g/L, the platelet count was

83 u 109/L, the blood glucose was 11 766 mmol/L. The

level of total serum IgG was 2.38 g/L (n.v. 8.0-18.0 g/L),

IgA < 0.26 g/L (n.v. 0.07-3.0 g/L), and that of IgM was

< 0.19 g/L (n.v. 0.05-2.5 g/L).

A bone marrow biopsy showed a lymphocytic infiltrate with nodular and trabecular patterns and hypocellularity of myeloid lineage.

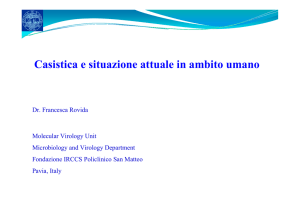

An accurate visual field examination revealed a left

homonymous hemianopsia and a cranial computed tomographic scan without injection of contrast material showed

hypodensity of the white matter of the occipital lobes.

Fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) and gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the

brain showed hypointense signals in T1-weighted and

hyperintense signals in T2-weighted images in the white

matter of the right and left occipital lobes without any mass

effect (Fig. 1).

Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML) is

a demyelinating disease of the central nervous system

and is caused by the papovavirus JC1. The main pathologic

features include multiple foci of myelin and oligodendroglial cell loss, hyperchromatic enlarged oligodendroglial nuclei, and bizarre astrocytes with enlarged multilobulated nuclei2.

The widespread use of immunosuppressive agents in

autoimmune diseases and organ transplantation, and, more

recently, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

led to an increase in the incidence of PML3,4. In other diseases, PML is still a rare and undiagnosed complication5

even though positive results for JC virus DNA testing of

the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) may yield the diagnosis

without brain biopsy6.

We report the case of a woman with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), in whom PML has been diagnosed

without brain biopsy.

Case report

A 60-year-old woman came to the Emergency Department reporting blurred vision and visual field impairment manifesting 1 month earlier.

She had a history of CLL lasting 10 years (Rai staging

system IV)7 and cyclically treated with chlorambucil and

prednisone. At the time of hospitalization she was on

Dipartimento di Emergenza e Accettazione (Direttore: Prof. Rodolfo

Proietti), *Istituto di Medicina Interna e Geriatria (Direttore: Prof.

Giovanni Gasbarrini), **Istituto di Malattie Infettive (Direttore:

Prof. Roberto Cauda), Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore,

Policlinico “A. Gemelli” di Roma

© 2004 CEPI Srl

118

Lorenzo Capaldi et al.

FIGURE 1. Magnetic resonance imaging axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery image showing

bilateral hyperintense signals in the white matter of the occipital lobes with sparing of the gray matter and no mass effect.

Lumbar puncture yielded a clear, normal-pressure CSF

with glucose and protein levels normal with respect to the

plasma values and 3 lymphocytes/mm3. Polymerase chain

reaction (PCR) examination of the CSF for the presence

of JC virus yielded a positive result.

On the basis of the FLAIR-MRI and CSF findings a

diagnosis of PML was made.

During the following weeks, the patient completely

lost her vision and developed left hemiparesis and her conditions progressively worsened. She was finally transferred to the Infectious Disease Department and during the

following months she developed tetraparesis, progressive mental impairment and coma. The patient died 8

months after the diagnosis was made.

DNA genome12. JC virus infection is ubiquitous and it is

thought to be asymptomatic in immunocompetent individuals13,14.

It is still being debated whether PML is due to reactivation of a latent childhood JC virus infection of the central nervous system, or to a cerebral primary infection in

an immunocompromised host15-19.

Several cases have been reported in association with

leukemia and lymphomas, cancer chemotherapy and

immunosuppressive treatment13,14.

A definitive diagnosis of PML requires evaluation of the

brain tissue, but recent studies indicate that the presence

of JC virus in the CSF may be identified by PCR with a

high specificity and sensitivity20.

The neuroimaging characteristics of PML are a decreased attenuation on computed tomographic scans and

a hyperintense signal on T2-weighted MRI. The lesions

most often involve the periventricular and subcortical

white matter of the occipitoparietal or frontal lobes.

Occasionally, the posterior fossa is involved too. Rarely,

the lesions show contrast enhancement or produce a mass

effect21,22.

In a prospective cohort study of AIDS patients with focal

brain lesions, the absence of a mass effect on neuroimaging

studies and a positive PCR testing for JC virus in the

CSF yielded a 0.99 probability of making a diagnosis of

PML6,23.

As in our patient, computed tomography of the brain

shows hypodense, non-enhancing lesions of the cerebral

white matter and the lesion extension is often less than

would be expected on the basis of the neurological symptoms. MRI, which proves to be more sensitive, typically

shows high intensity abnormalities in the white matter in

T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

Discussion

CLL is the most prevalent leukemia in western countries8. Symptomatic central nervous system involvement

with CLL has been reported to occur in < 1% of cases9

while PML is one of the opportunistic infections of the central nervous system in patients with CLL3,5.

PML, first recognized in 1958 in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia10,11, was a relatively rare condition prior to the emergence of AIDS and today it is

mandatory to rule out PML in AIDS patients with focal

brain symptoms5.

In 1971, Padgett et al.10 reported the cultivation of a

papova-like virus from human brain cells with PML and

that virus was called JC (JC are the initials of the patient

from whom the first virus isolates were obtained). JC is

a polyomavirus and, as such, is a member of the Papovaviridae family. These are small, non-enveloped viruses with a covalently closed, circular, doubled-stranded

119

Ann Ital Med Int Vol 19, N 2 Aprile-Giugno 2004

images and low intensity abnormalities in T1-weighted

images, not enhanced after gadolinium and with no mass

effect24. This characteristic helps to differentiate PML

from lymphomatous infiltration of the central nervous

system25,26.

The clinical manifestations of PML include visual

deficit, upper motor neuron weakness, and an altered

mental state. Language and speech dysfunction, extrapyramidal syndromes, cerebellar disorders, sensory deficits,

headaches, and seizures may also occur27,28. Most commonly the patient’s conditions deteriorate rapidly, and

death usually occurs within 6 months of the diagnosis5.

PML may be distinguished from central nervous system

lymphocytic infiltration and from encephalitis caused by

others viruses on the basis of the MRI pattern (sparing of

the cortical gray matter, no enhancement after gadolinium)24, by the normal or near normal characteristics of the

CSF and by evidence of JC virus in the CSF at PCR

analysis29. This method can obviate the need of brain

biopsy, allowing the detection of the viral sequences in

> 85% of cases, with no false positive results30,31. A positive result has to be considered diagnostic only when

associated with characteristic findings on clinical and

radiographic examinations, while a negative result does not

exclude the diagnosis when these findings are present29,30.

Unfortunately, no treatment is currently available for this

complication. A few reports refer a somewhat delayed progression of the disease after cidofovir therapy32.

Physicians must consider carrying out a PCR test for JC

virus DNA on the CSF to rule out the diagnosis of PML

in patients with CLL or an immunodeficiency state with

a history of progressive neurologic deficit and white matter lesions at cerebral computed tomography or MRI

scans.

In this clinical setting, clinicians need to keep immunodepression-related infectious processes high in the list of

probabilities, with PML ranking at the first place.

complicanza del paziente affetto da AIDS, ma è presente anche in altre condizioni di immunodepressione come

la leucemia linfatica cronica.

Parole chiave: AIDS; Leucemia linfatica cronica; Leucoencefalopatia multifocale progressiva; Liquor cerebrospinale; Papovavirus JC.

References

01. Major EO, Ault GS. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: clinical and laboratory observations on a viral induced

demyelinating disease in the immunodeficient patient. Curr

Opin Neurol 1995; 8: 184-90.

02. Gallia GL, Houff SA, Major EO, Khalili K. JC virus infection

of lymphocytes - revisited. J Infect Dis 1997; 176: 1603-9.

03. Richardson EP Jr. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

30 years later. N Engl J Med 1988; 318: 315-6.

04. Rosai J, ed. Ackerman’s surgical pathology. St Louis, MO:

Mosby-Year Book, Inc, 1996.

05. Berger JR, Concha M. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: the evolution of a disease once considered rare. J Neurovirol 1995; 1: 5-18.

06. Antinori A, Ammassari A, De Luca A, et al. Diagnosis of AIDSrelated focal brain lesions: a decision-making analysis based

on clinical and neuroradiologic characteristics combined with

polymerase chain reaction assays in CSF. Neurology 1997; 48:

687-94.

07. Rai KR, Sawitsky A, Cronkite EP, Chanana AD, Levy RN,

Pasternack BS. Clinical staging of chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Blood 1975; 46: 219-34.

08. Landis SH, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics,

1999. CA Cancer J Clin 1999; 49: 8-31.

09. Bower JH, Hammack JE, McDonnel SK, Tefferi A. The neurologic complications of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia.

Neurology 1997; 48: 407-12.

10. Padgett BL, Walker DL, ZuRhein GM, Eckroade RJ, Dessel

BH. Cultivation of papova-like virus from human brain with

progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Lancet 1971; 1:

1257-60.

11. Aström KE, Mancall EL, Richardson EP Jr. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: a hitherto unrecognized complication of chronic lymphatyc leukemia and Hodgkin’s disease.

Brain 1958; 81: 93-111.

12. Shah KV. Polyomaviruses. In: Fields BN, Knipe DM, Howley

PM, et al, eds. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA:

Lippincott-Raven Publishers, 1996: 2027-43.

Riassunto

13. Greenlee JE. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy.

Progress made and lessons relearned. N Engl J Med 1998; 338:

1378-80.

Viene presentata una rara causa di perdita progressiva

del visus ad insorgenza acuta. Una donna di 60 anni, con

storia di leucemia linfatica cronica da circa 10 anni, venne inviata in Pronto Soccorso per la comparsa improvvisa di un’emianopsia omonima nel sospetto di un accidente

cerebrovascolare. Una tomografia assiale computerizzata e una risonanza magnetica nucleare mostrarono lesioni della sostanza bianca bilateralmente nelle regioni occipitali compatibili con leucoencefalopatia multifocale

progressiva. Un esame del liquido cerebrovascolare risultò

positivo per il papovavirus JC. La leucoencefalopatia

multifocale progressiva dovuta al virus JC è una tipica

14. Greenlee JE. Polyomavirus. In: Richman DD, Whitley RJ,

Hayden FG, eds. Clinical virology. New York, NY: ChurchillLivingstone, 1997: 549-67.

15. Arthur RR, Shah KV. Occurrence and significance of papovaviruses BK and JC in the urine. Prog Med Virol 1989; 36: 4261.

16. Schneider EM, Dorries K. High frequency of polyomavirus

infection in lymphoid cell preparations after allogenic bone

marrow transplantation. Transplant Proc 1993; 25: 1271-3.

17. White FA III, Ishaq M, Stoner GL, et al. JC virus DNA is present in many human brain samples from patients without progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Virol 1992; 66:

5726-34.

18. Cid J, Revilla M, Cervera A, et al. Progressive multifocal

120

Lorenzo Capaldi et al.

leukoencephalopathy following oral fludarabine treatment of

chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Ann Hematol 2000; 79: 392-5.

26. Saad ED, Thomas DA, O’Brien S, et al. Progressive multifocal

leukoencephalopathy with concurrent Richter’s syndrome. Leuk

Lymphoma 2000; 38: 183-90.

19. Zabernigg A, Maier H, Thaler J, Gattringer C. Late onset fatal

neurological toxicity of fludarabine. Lancet 1994; 344: 1780.

27. Fong IW, Toma E. The natural history of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in patients with AIDS. Canadian PML

Study Group. Clin Infect Dis 1995; 20: 1305-10.

20. McGuire D, Barhite S, Hollander H, Miles M. JC virus DNA

in cerebrospinal fluid of human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients: predictive value for progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Ann Neurol 1995; 37: 395-9.

28. Conway B, Halliday WC, Brunham RC. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy: apparent response to 3’-azido-3’-deoxythymidine. Rev Infect Dis 1990; 12: 479-82.

21. Whiteman ML, Post MJ, Berger JR, et al. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy in 47 HIV-seropositive patients: neuroimaging with clinical and pathologic correlation. Radiology

1993; 187: 233-40.

29. Fong IW, Britton CB, Luinstra KE, Toma E, Mahony JB.

Diagnostic value of detecting JC virus DNA in cerebrospinal

fluid of patients with progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. J Clin Microbiol 1995; 33: 484-6.

22. Finelli PF. Images in neurology. Mass effect in progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Arch Neurol 1998; 55: 1148-9.

30. D’Arminio Monforte A, Cinque P, Vago L, et al. A comparison of brain biopsy and CSF-PCR in the diagnosis of CNS

lesions in AIDS patients. J Neurol 1997; 244: 35-9.

23. Chukwudelunzu FE. Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy

as an initial manifestation of AIDS. Hospital Physician 2001;

37: 65-70.

31. Mossad SB. Diagnosis: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy. Clin Infect Dis 2000; 31: 125-6.

24. Edelman RR, Warach S. Magnetic resonance imaging. Part 1.

N Engl J Med 1993; 328: 708-16.

32. Bagnato F, Pietropaolo V, Di Taranto C, Lorenzano S, Toni D.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia complicated by progressive

multifocal leukoencephalopathy without apparent immunodepression. Eur J Neurol 2001; 8: 367-8.

25. Atlas SW. Intraaxial brain tumors. In: Atlas SW, ed. Magnetic

resonance imaging of the brain and spine. New York, NY:

Raven Press, 1991: 223-326.

Manuscript received on 10.10.2003; accepted on 3.2.2004.

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Luca Miele, Istituto di Medicina Interna e Geriatria, Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, Policlinico “A. Gemelli”, Largo A. Gemelli 8,

00168 Roma. E-mail: [email protected]

121

![Yellow-Fever_SA_2012-Ox_CNV [Converted]](http://s1.studylibit.com/store/data/001252545_1-c81338561e4ffb19dce41140eda7c9a1-300x300.png)