PhD-IBMG-II-Matinée

Genetic information

Genomi, geni, organizzazione comparativa

Funzioni, famiglie, mutazioni, evoluzione

Mutazione e riparazione del DNA

NGS

Alternative splicing

Il genoma umano 3,200 Mb

23 cromosomi (x2)

The Human Genome Project

Animated tutorials on the Human

Genome Project:

http://www.genome.gov/Pages/

EducationKit/

(free downloads or on-line view)

1. DNA sequence

Sito NCBI Genomes Eukaryotic (Mammals)

Genomic Data

1990-2003

Human Genome Project

2001

The HGP consortium and Celera release the first draft of

95% Human Genome

2003

Sequencing is completed

2001-today

Several other genomes sequenced

NGS technology

2007

The ENCODE project releases results on 1% human genome

2012

The ENCODE project publishes complete results

Table 1-1 (part 2 of 2) Molecular Biology of the Cell, Fifth Edition (© Garland Science 2008)

prokaryotes

5x

50x

Eukaryotes and Prokaryotes

different genome organization

different gene structure

The rationale for genom organization in Prokaryotes and Eukaryotes is

fundamentally divergent

Prokaryotes: essentials, reproductive speed, high mutation rate

Eukaryotes: diversification, adaptation, reassortment

Let’s see first some common traits:

The overall «order» of transcription units (see below for definition) does

not follow a simple logic.

Transcription Units are in both orientations on the chromosomes

Noncoding parts are present that are either functional to chromosome

dynamics (e.g. origins of replication) or mobile genetic elements (e.g.

virus, transposons).

Transcription Units are in both orientations on the chromosome

Transcription Unit (T.U. or TU) is a part of DNA that is found transcribed

in RNA in at least some circumstances. A «promoter» or «promoter-like»

sequence always flanks 5’ a TU.

5’

3’

P

5’

3’

Why do we say «TU» and not «gene».

TU is a physical entity, experimentally proven.

The «gene» is a concept

Definitions of «gene»

-

One gene, one character

One gene, one protein

One gene, some protein isoforms (after alternative splicing)

One gene, one molecular function

One gene one functional module (Molecular Biology)

One gene one Transcriptional Unit (Genomics)

Protein coding genes

Even though proteins that perform similar functions are extraordinarily conserved,

genes may be remarkably different in genomic organization

Essentials:

promoter

ORF

terminator

Prokaryotic genes essentially follow the operon model

leader or 5’UTR

DNA

5’

tail or 3’-UTR

ORF2

ORF1

Transcriptional

termination

ORFn

This part is

copied into RNA

(transcription)

Coding A

Coding B

promoter

(position site for

RNA Polymerase)

Coding N

Spacers (0-few bp)

ATG 1st codon

operator (regulatory element)

Stop codon

Transcribed RNA is «polycistronic» (i.e. contain more than one string of information

Un esempio molto noto in E.coli: l’operone del lattoso

LacZ: -galactosidase cleaves lactose to galactose + glucose

Lac Y: lactose permease, pumps in lactose against electrochemical gradients

LacA: Thiogalactoside transacetylase.

Lac I: lac repressor

Eukaryotes

Protein coding genes are often discontinuous.

Coding sequences (exons) are interrupted by noncoding sections (introns)

Transcribed RNAs can be mono-cistronic or polycistronic

3’utr

For large eukaryotic genomes, the presence of introns is a complication.

In this case we should consider separately two distinct entities:

1. The genomic sequence (i.e. the Transcription Unit)

2. The RNA produced after processing of the primary RNA transcript

(mRNA in the case of protein-coding genes)

Eukaryotes: monocystronic

parts remaining in mRNA

5’

Intron N

Intron 1

poly(A) signal

Intron 2

Regulatory

region and

promoter

3’-UTR

(regulatory)

Exon 1

Exon 2

this part is copied in primary RNA

Exon 3

Exon N

Il processo di splicing congiunge le diverse parti che si ritroveranno nell’RNA

messaggero

Comparative:

Human

Yeast

Drosophila

Mais

A 50 Kb tract of the Human genome

25K

50K

H. sapiens

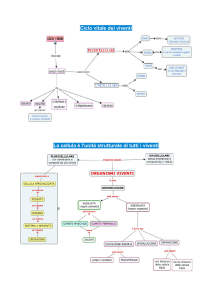

Genoma umano

3200 Mb

DNA intragenico

2000 Mb

Sequenze di geni e genecorrelate 1200 Mb

Coding

Sequenze

correlate

1152 Mb

48 Mb

Pseudogeni

Ripetizioni

intersperse 1400

Mb

Altre regioni

intrageniche

600 Mb

Introni, UTR

Frammenti

genici

Microsatelliti

90 Mb

LINE 640

Mb

Elementi LTR

250 Mb

Varie

510 Mb

SINE 420

Mb

Trasposoni DNA

90 Mb

Interspersed repetitive elements - Mobile genetic elements

pseudogenes

Second class of pseudogenes

are gene copies inactivated

by multiple mutations, or:

Retrotranscription-insertion

Genes

Protein coding (mRNA)

noncoding: ncRNA

Range

1–cent.

0-cent.

Range

30- some Kb

300- some Mb

100- some Kb

-

z

I valori mostrati in tabella sono i valori medi

2Kb- 100Mb

Range (appr.)

While genes vary enormously in size from bacteria to mammals, due to intronic

prevalence, coding regions (ORF) are quite uniform, possibly due to protein

structural constraints.

Predicted ORF products mean size in completely sequenced organisms

Average a.a. 128 Da

in peptides: 110 Da

Functional

catalogue

Gene functions

Protein coding genes are organized in Gene families

Bacillus subtilis

Figure 1-24 Molecular Biology of the Cell, Fifth Edition (© Garland Science 2008)

Duplicazioni per ricombinazione diseguale

Traslocazioni

Duplicazioni esoniche

Figure 1-23 Molecular Biology of the Cell, Fifth Edition (© Garland Science 2008)

Figure 1-25a Molecular Biology of the Cell, Fifth Edition (© Garland Science 2008)

Figure 1-25c Molecular Biology of the Cell, Fifth Edition (© Garland Science 2008)

Le similitudini tra proteine hanno rivelato un addizionale

livello di organizzazione:

il dominio

Il dominio è una sottostruttura prodotta da qualunque parte

del polipeptide che si possa ripiegare in una conformazione

stabile indipendentemente dal resto della proteina.

Il concetto di dominio è molto importante in genomica,

perchè spesso i domini delle proteine sono codificati da

singoli esoni, giustificando la teoria dell’”exon shuffling” per

l’evoluzione delle proteine.

Mutation & Repair

Vai a 33

M-Phase

Ripasso da Biologia della Cellula

Ripasso da Biologia della Cellula

La domanda che affronteremo oggi è:

Come si fronteggia la possibilità di errore durante la fase di replicazione

del DNA ?

Come viene risolto il problema di eventuali danneggiamenti chimicofisici del DNA in cellule stazionarie ?

Mutazioni e riparazione del DNA

Mantenere inalterato il proprio patrimonio genetico e

passarlo inalterato alla discendenza è un necessità assoluta

per gli organismi viventi.

Qualsiasi irregolarità durante la replicazione del DNA oppure

qualsiasi danno chimico-fisico che succeda al DNA in fase non

replicativa

è potenziale fonte di mutazione

Tutti gli organismi mantengono il più possibile inalterato il DNA,

tramite complicati e dispendiosi meccanismi di riparazione e

manutenzione

cambio di una base

5’

5’

5’

5’

5’

DNA

mutato

scivolamento durante la replicazione

Risultato di una mutazione

In aploidi (es.: E. coli)

se tollerata

si fissa nella discendenza

se non tollerata

la cellula muore

In eucarioti pluricellulari (es. Uomo):

In cellule somatiche

se tollerata

a) nulla

b) la cellula trasforma (cancro)

In cellule germinali

se non tollerata

la cellula muore

se tollerata

si fissa nella discendenza

se non tollerata

a) la cellula muore

b) lo sviluppo non è possibile

Esempi:

Riarrangiamenti o ricombinazioni (grandi mutazioni)

Transposition = change in the order of two or more sequences

Crossing-over = exchange of fragments between DNA molecules

Deletion = loss of a fragment of DNA

Duplication = replication of a fragment of DNA

Amplification = repeated replication of a DNA fragment

Insertion = addition of a fragment of DNA within a sequence

Il “peso” di una mutazione dipende dal contesto in cui la mutazione avviene

All’interno di una sequenza codificante:

Il codice genetico è ridondante

Deletions & insertions

(= 1 a.a.)

(indels)

La proteina perderà un aminoacido,

ma il resto è invariato.

(reading frame changed)

La proteina cambia totalmente a

partire dal punto della mutazione

Frequenza dei cambiamenti

La velocità con la quale si fissano le

mutazioni dipende da quanto la funzione

di ogni particolare tratto di DNA (per es.:

un gene) dipende dalla sua sequenza

nucleotidica.

La fedeltà di mantenimento della sequenza del

proprio DNA è essenziale per ogni forma di vita

Fedeltà nella replicazione

Replicazione senza “proofreading” (3’-5’ esonucleasi): 1 / 104 - 105

Replicazione con proofreading:

1 / 107 – 108

Riparazione degli errori replicativi:

Mismatch repair

1 / 109

Riparazione dei danni accidentali in fase non replicativa

(vari)

Mantiene la frequenza di mutazione a < 1 / 109

1° categoria:

Mutazioni che avvengono in fase replicativa, per errori del replisoma che

non vengano riparati immediatamente dalla DNA Polimerasi stessa, con il

meccanismo di “proofreading” (3’5’ esonucleasi)

Errori dovuti a errata incorporazione: attività proofreading (3’-5’-esonucleasi) della DNA Polimerasi

(vedi: Replicazione)

1° categoria: Errori residui in replicazione (1 / 107 – 108).

Vengono riparati dal meccanismo del Mismatch Repair

(riparo dell’appaiamento scorretto).

E. coli: sistema enzimi MutS, MutL, MutH.

Uomo: enzimi MSH (MutS Homologs), MLH, PMS

Mismatch

T:G

MutS

MutL

MutH

ATP

DNA Pol. I

DNA Ligase

DNA ligasi salda l’ultima interruzione

Distinzione del filamento “vecchio” da

quello neosistetizzato in E. Coli.

E. Coli metila tutte le

sequenze 3’-GATC-5’

(dam metilasi)

Il DNA neosintetizzato per un

po’ resta libero da metilazioni

MutH taglia il filamento

non metilato

Eucarioti: esistono sistemi molto simili.

Uomo: enzimi MSH (MutS Homologs)

la predisposizine genetica al tumore al colon è dovuta a mutazioni in uno dei

geni che codificano proteine del sistema (MSH2)

Il sistema della dam metilasi, tuttavia, è limitata a E. coli. Non si sa ancora con

esattezza come, negli organismi superiori, il sistema riconosca il filamento

neosintetizzato.

2° categoria:

Mutazioni post-replicative

1.

Alterazioni spontanee

2.

Alterazioni dovute a mutageni

Post-replicative DNA repair is active in all cells,

including terminally differentiated cells such as

myocytes or neurons that will never replicate

Idrolisi del legame glicosidico e perdita della base

La rimozione di purine

(max: G) è massiva: in

un giorno, dal genoma

di un mammifero

vengono perse circa

10.000 purine / cellula.

Alterazioni spontanee

deossiriboso

Negli organismi superiori, molte

C sono metilate: una C metilata

se deaminata dà una T.

Per evitare l’accumulo di

mutazioni, esiste un sistema di

riparo che, in presenza di

appaiamenti errati T:G, rimuove

selettivamente le T, riportando

la situazione alla normalità.

Base deamination is spontaneous: circa 100 bases / day / cell.

Some chemical compounds increase the rate of deamination, such as nitrous acid

(deaminates A, C and G) or sodium bisulfite (deaminates C)

Pairs with C

rather than T

Cytosine deamination uracil

(pairs with A rather than G)

Guanine deamination xantine (blocks replication)

radiation

UV

analoghi delle basi

agenti intercalanti

Riparazione

Talune modificazioni possono essere corrette in situ da appositi enzimi

Riparazione dei dimeri di timina con fotoliasi (E.coli) (no eucarioti)

(Base excision repair – BER)

Riparazione mediante escissione di base

La maggior parte delle piccole modificazioni delle basi, come

deaminazioni, alchilazioni etc., sono riconosciute da una batteria di enzimi

appositi che continuamente percorrono il DNA, trovano le alterazioni e

rimuovono le basi danneggiate tagliando il legame glicosidico.

Le DNA glicosilasi

(Base excision repair – BER)

Dopo il taglio, il sito viene

riconosciuto da speciali endonucleasi,

chiamate AP-endonucleases

che rimuovono lo zucchero dallo

scheletro del DNA.

In seguito DNA polimerasi e DNA

ligasi riparano il “gap”.

Alcuni agenti fisici o composti mutageni inducono cambiamenti più

grandi, che danno deformazioni più importanti nella struttura della

doppia elica.

(Alchilazioni, dimeri di timina, intercalanti)

Questi vengono riparati con il meccanismo della

NER (nucleotide excision repair).

NER nucleotide

excision repair

(E.coli)

NER

E.coli: Uvr A, UvrB, UvrC, UvrD

H. sapiens: XPC, XPA, XPD, XPF (ERCCI), XPG

(dove “XP” sta per xeroderma pigmentosum)

Mutazioni puntiformi e

riarrangiamenti

1) durante la fase di replicazione del DNA

1-Proofreading

2-Mismatch Repair

2) Non dipendenti dalla replicazione del DNA

- spontanee

- da agenti esterni

1-Base excision repair

2-Nucleotide excision repair

3-Direct reversal

Se la lesione nel DNA non viene riparata .....

DNA Polimerasi “trans-lesione”

Generazione di “double strand breaks” (DSB)

Se la lesione nel DNA non viene riparata .....

DNA Polimerasi translesione: famiglia Y

In figura, sono rappresentate

le proteine di E. coli

DSB=double strand break

Se la lesione riguarda entrambi i filamenti ?

riparazione di tipo ricombinativo

Ricombinazione Omologa

Concetto di omologia – concetto di identità

Ricombinazione generale o ricombinazione omologa

In caso di danni del doppio filamento (DSB)

?

Il meccanismo di riparazione funziona

schematicamente come se ognuno dei due

filamenti lesi andasse a recuperare lo

“stampo” dal cromosoma omologo

Modello di riparazione di

DSB mediante

ricombinazione omologa

Ligazione dei

filamenti

2 giunzioni di

Holliday

La risoluzione del chiasma porta a:

Quali enzimi portano avanti la ricombinazione riparativa ?

La ricombinazione omologa in generale

Crossing-over meiotico

Trasfezione sperimentale di cellule con DNA ricombinante

Divisione cellulare:

http://www.cellsalive.com

/mitosis.htm

Only in meiosis

Crossing-over

(ricombinazione)

Ricombinazione sito-specifica

Nella ricombinazione degli elementi mobili

Caratteristica principale della ricombinazione omologa è che le due

molecole di DNA che ricombinano devono essere “omologhe”

ovvero

la loro sequenza deve avere un elevato grado di identità per

consentire lo scambio di filamenti e la migrazione per lunghi tratti.

trasposizioni, retrotrasposizioni, delezioni e inserzioni

dipedono da un tipo di ricombinazione diversa dalla ricombinazione

omologa

•

ricombinazione eterologa

•

ricombinazione sito-specifica

La ricombinazione sito-specifica:

CSSR (conservative site-specific recombination)

elemento mobile

brevi sequenze identiche

DNA ricevente

elemento mobile “integrato” nel DNA ricevente

Questo tipo di ricombinazione porta avanti diversi eventi:

inserzione

delezione

inversione

Le “ricombinasi” sono enzimi

che riconoscono corte sequenze

che si trovano, come ripetizioni

invertite, ai lati del punto di

inserzione

L’integrazione del fago lambda nel cromosoma di E. coli è un fenomeno

di ricombinazione sito specifica.

Lisogeno

Se il fago procede nella via lisogenica, si ha integrazione del DNA fagico nel

cromosoma di E. coli (ricombinazione sito-specifica).

The Human Genome Project

Hierarchical

Shotgun

The sequencing phase

Fragments are cloned into appropriate

vectors

Individual recombinants (bacterial clones) are grown, purified and sequenced (Sanger)

Il clonaggio classico

Sistema vettore-ospite in E. coli

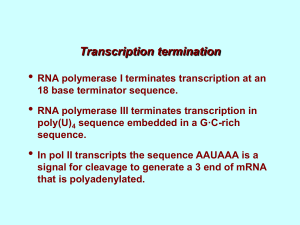

Dideoxy-sequencing: the “chain-terminator” method of Sanger:

il metodo di maggior successo, si basa sulla sintesi di catene di DNA

complementari troncate in corrispondenza di una determinata base.

La sintesi avviene in presenza di molecole particolari: i di-deossi-nucleotidi

d

Reazione con di-deossi-Guanosintrifosfato

The label is usually 32P,

so that detection requires

autoradiography

Separazione con

elettroforesi

Una successiva evoluzione del metodo ha permesso l’automazione del

sequenziamento del DNA. In questo caso, i nucleotidi dideossiterminatori sono marcati mediante l’addizione di un gruppo chimico

fluorogenico, diverso per ogni base.

La reazione viene fatta insieme, ed ogni molecola “terminata” sarà

marcata col colore corrispondente alla base relativa.

Sequenziamento automatico del DNA

con dideossinucleotidi marcati con

fluorofori.

Le reazioni di terminazione di catena

vengono effettuate in una singola

provette, con ciascun

dideossinucleotide marcato con un

fluoroforo diverso.

Il frazionamento viene effettuato

con elettroforesi capillare.

Movie 1

Movie 2

Post-genome

1. Human genetic variation

1000 Human Genome project

exome project (exon-targeted resequencing)

2. Comparative genomic analysis

3. Functional analysis (ENCODE)

transcriptome

proteome

interactome

epigenome

…

Amplification of fragments

fragmentation

Adapter ligation

No cloning step

PCR

Library

No cloning step

NGS sequencing reads

Reads are mapped to the reference genome

reference genome

In re-sequencing, the number of independent sequences

(called «reads») is more important than lenght

The % of reference genome that is represented in «reads» is

the «coverage».

Other essential aspects:

1) speed

2) cost

3) error-to-depth ratio

Next Generation Sequencing

(deep-sequencing / mass sequencing)

generation of “DNA-nanoclones” on distinct solid surfaces by PCR or singlemolecule isolation

highly parallel in situ sequencing

record read-out i.e. millions or short sequences (“reads”)

align reads on genomes or assembly

Next generation sequencing methods:

Number of molecules per sequence

• Amplification

• Single-molecule

Biochemical measurement

• Sequencing by synthesis

(Sanger is synthesis + termination)

• Nucleotide chemistry

• Associated chemistry

• Sequencing by annealing and ligation

• Sequencing by direct physico-chemical measurements

Detection

• Optical detection

• Ion or conductance detection

Amplification by emulsion PCR (Roche 454, Polonator)

Biotinylated

template

http://www.pyrosequencing.com/DynPage.aspx?id=7454

In the second case, a surface sequencing is used

This is the 5’

Sequencing

direction

-CGCCTT

ATACGTCGTACTCGCAAGGCG

This must be 3’

This is the 3’

This is 5’

CGCCTT-

AAGGCGTACGTCGTACTCGCAA

Sequencing

direction

CGCCTT-

AAGGCGTACGTCGTATCTCGCAA

TTGCGA

This is the 3’

Sequencing

direction

Il vetrino viene chiuso per dare una camera microfluidica

Le frecce indicano il flusso di reagenti chimici necessari alle reazioni che

rivelano progressivamente l’ordine dei nucleotidi di ciascun frammento

Un laser scanner registra in continuo la fluorescenza in tutto il

vetrino, ogni segnale corrisponde ad una «base» (es. Red=A,

green=T, yellow=G, blue=C ) leggendo così tutte le sequenze

Reading: 2 spots are exemplified here:

Immagine monocolore: sono esguiti per ogni posizioe quattro cicli

successivi, con ciascuna delle basi (come reversible terminator

Il «readout» sono milioni di corte sequenze (secondo i tipi, da 30 a 500 nucleotidi)

che vengono chiamate «reads»

Tipicamente, ogni campione produce tra 10 e 100 milioni di «reads»

I «reads» vengono quindi allineati al genoma e assegnati di conseguenza ai diversi

geni.

sequence

# of reads map

region

CTAGTCATGCTCTCGATCGGTCATAGTTTAGTCTGACT

12

Chr 1: 12,345,678-12,345,711

CHD1 coding

TTAAAGTACTGTCATGATTTCATGCTAGCTTTTCAAAG

3

Chr 7: 1,987,654-1,987,694

PTT1 intron

GGCTACTAGTCTATTACAAGGGCATCGCGGATCGCGT

1

Chr 16: 23,456,711-23,456,755

intergenic

22

Chr 1: 12,345,123-12,345,183

CHD1 coding

....

....

TACTGCTGACGCCGCATGCATTTACGCTGCGGCATCGG

....

Illumina-Solexa Genome Analyzer

Read lengths: 36 bp, 50 bp, 75 bp, 100bp for fragment or paired-end sequencing

Throughput (reads): 120 million reads per run, fragment

SoliD – Applied Biosystems

Read lengths: 50 bp fragment, 25 bp and 35 bp paired

Throughput (reads): > 160 million reads per slide, fragment

Roche – 454

Read lengths: Averaging 350 - 400 bp

Throughput (reads): ~1 million reads per run

Extensive sequencing of RNA from several cell types and tissues has provided

answer to a long-lasting question:

Why do Humans have so few genes ?

To be sequenced, RNA must be copied to DNA (called cDNA – complementary DNA)

This is done using an enzyme called Reverse Transcriptase (RT)

cDNA is then fragmented, linked to adaptors and used to generate libraries for NGS

Wang et al. (2009). Nat. Rev. Genet. 10:57-69

Wang et al. (2009)

Figure 1 | A typical RnA-seq

experiment. Briefly, long

RNAs are first converted into

a library of cDNA

fragments through either

RNA fragmentation or DNA

fragmentation (see main

text). Sequencing

adaptors (blue) are

subsequently added to each

cDNA fragment and a short

sequence is obtained from

each cDNA using highthroughput sequencing

technology. The resulting

sequence reads are aligned

with the reference genome or

transcriptome, and classified

as three types: exonic reads,

junction reads

and poly(A) end-reads. These

three types are used to

generate a base-resolution

expression profile for

each gene, as illustrated at

the bottom; a yeast ORF with

one intron is shown.

Information is dependent on the kind of RNA preparation. Due to the uneven

representation of each RNA species, it is unpractical to run RNA-Seq analysis using

«total RNA preparations» (most of the reads would map to highly represented RNAs,

whereas rare RNA wouldn’t be represented at all in the sequencing library)

Cells, tissue

Tot RNA

fractionation

By type:

non-rRNA

all nonribosomal

By size:

Small < 200 nt

Long > 200 nt

small noncoding

coding + other

By adds:

poly(A)+

poly(A)-

>99% coding

large number noncoding

noncoding

By location:

nuclear

cytoplasmatic

snRNA, snoRNA, lncRNA

coding, noncoding

By function:

exome

microarray-selected

coding exons

guanine-N7methyltransferase

Elongation

factor

EJC deposited 20-24 nt upstream the

exon-exon junction

Splicing factors and snRNPs are replaced by the

EJC (exon junction complex) proteins

From Aguilera 2005, Curr Op Cell Biol, 17:242.

How prevalent is splicing (i.e. exon-intron gene organization)

in different organisms ?

S. cerevisiae

has only 253 introns (3% of genes),

only 6 genes have 2 introns.

S. pombe

43% of the genes have introns, many

of them contains >1 intron

H. sapiens

>99% of genes contain multiple introns

(40-75 nt)

Average human gene:

Length: 28,000 bp

No. of exons: 8.8

Exon length: 120 bp

No. of introns: 7.8

Intron length: 10 to >100.000 bp

Da «intronless» a pochi introni, a

parecchie decine

one intron in the human neurexin gene is approx. 480,000 nt !

Lo splicing alternativo consiste nella scelta di considerare esoni o

introni alcune sequenze.

Storico: 1983

Un gene umano va incontro a

processamento differenziale

La calcitonina è un ormone costituito

da un polipeptide di 32-aminoacidi che

viene prodotto, negli esseri umani,

dalle cellule parafollicolari della tiroide.

La principale funzione della calcitonina

è l'abbassamento della concentrazione

di calcio nel sangue

CGRP is produced in both peripheral

and central neurons. It is a potent

peptide vasodilator and can function in

the transmission of pain. In the spinal

cord, the function and expression of

CGRP may differ depending on the

location of synthesis.

Alternative Splicing

may concern one or

more exons.

Quite often many

isoforms are coexpressed;

sometimes there are

tissue-specific

isoforms.

Alternative Splicing of fibronectin pre-mRNA

Introns are drawn not to scale

Alternative splicing

H. sapiens

S. cerevisiae:

H. sapiens:

Estimated number of protein-coding genes: < 22,000

Estimated number of proteins: > 90,000

253 genes contain introns

only 3 genes shown experimentally to undergo alternative splicing

>99% predicted to have exon-intron structure

>90% predicted to undergo alternative splicing

Materiale per uso didattico

AS in many cases give rise to proteins with differential functions and roles.

One example is already well-known in this course: ERBB4

(e) Isoforms of the Slo protein lacking sequences encoded by the

STREX exon have fast deactivation kinetics and low Ca 2+ sensitivity,

whereas isoforms containing STREX-encoded sequences have slower

deactivation kinetics and higher Ca 2+ sensitivity.

From: Graveley BR (2001) Trends Genet., 17:100-106.

Fig. 1. Alternative splicing of the slo gene.

(a) The mammalian cochlea. The cochlea

is a snail-like structure of the inner ear

that contains hair cells organized along a

basilar membrane. The basilar membrane

traverses the length of the curled-up

cochlea.

(b) The cochlea is sliced transversely as

shown in (a) and the section of the

cochlea containing the basilar membrane

and the hair cells depicted. There are four

rows of hair cells, one inner hair cell and

three outer hair cells, situated above the

basilar membrane.

(c) The cochlea is unrolled to reveal the

basilar membrane viewed from above. The

four hair cells are arranged in rows along

the length of the basilar membrane. The

hair cells are tuned to unique narrow

sound frequencies along the basilar

membrane creating a tonotopic gradient.

At one end of the membrane, hair cells

are tuned to respond to a frequency of 20

Hz, where as hair cells at the other end

respond to 20 000 Hz.

(d) Organization of the human slo gene.

The exon–intron organization of the

slogene (determined by an analysis of

draft sequence of the human genome) is

depicted. The constitutive splicing events

are indicated below the gene and

alternative splicing events are depicted

above the gene. The constitutive exons

are white and the alternative exons are

shaded. The STREX exon is purple.

present in the postsynaptic cell, and thus function to initiate synaptogenesis. In contrast, b-neurexin I containing exon 20 encoded sequences can not

interact with neuroligins. This form of b-neurexin I might indirectly function in releasing synapses.

Neurexins

From: Graveley BR (2001) Trends Genet., 17:100-106.

Drosophila Dscam gene provides probably the extreme example of

alternative splicing.

Perhaps the most complex event that takes place during development

is the migration and connection of neurons. Even in a ‘simple’ organism

such as Drosophila melanogaster, which contains only ~250 000

neurons, accurately wiring neurons together would appear to be a

daunting task.

In flies, the gene encoding the Down syndrome cell adhesion molecule

(Dscam) appears to fulfill at least part of this role. Dscam encodes an

axon guidance receptor with an extracellular domain that contains ten

immunoglobulin (Ig) repeats. The most striking feature of the Dscam

gene is that it’s pre-mRNA can be alternatively spliced into over

38,000 different mRNA isoforms (Fig. 3a). This is 2–3 times the

number of predicted genes in the entire organism !

Each mRNA encodes a distinct receptor with the potential ability to

interact with different molecular guidance cues, directing the growing

axon to its proper location.

as an axon guidance receptor. It is thought that each Dscam variant will interact with a unique set of axon guidance cues.

The form of Dscam shown on the left will interact with guidance cue A. The form of Dscam shown on the right contains different sequences encoded by exons

4, 6 and 9 and thus interacts with guidance cue B, rather than guidance cue A. Neurons expressing the form of Dscam shown on the right will be attracted in a

different direction than neurons expressing the form shown on the left.

From: Graveley BR (2001) Trends Genet., 17:100-106.

Potentially 38,000 splicing variants

How extensive is Alternative Splicing usage in Humans ?

Exon-exon junction micro-arrays

Oligonucleotide probes, typically 25–60 nucleotides in length, can be designed to hybridize to isoform-specific mRNA regions.

Recently, alternative splicing microarrays have been designed with probes that are specific to both exons and exon–exon junctions.

Probes e1, e2 and e3 are exon specific, whereas j1–2, j2–3 and j1–3 are isoform-specific junction probes. Some arrays also

contain intron probes (i1 and i2) to indicate signals from pre-mRNA. Various array design and data processing strategies facilitate

the quantitative analysis of alternative splicing patterns, some of which have been subsequently confirmed by PCR after reverse

transcription of RNA (RT-PCR). Johnson et al.(2003) used arrays with probes for all adjacent exon–exon junctions in 10,000 human

genes and hybridized these with samples from 52 human tissues and cell lines. This revealed cell-type-specific clustering of

alternative splicing events, and allowed the discovery of new alternative splicing events. Pan et al. analysed 3,126 known cassettetype alternative splicing events in mouse using exon-specific and exon–exon junction probes. Analysis of RNAs in ten tissues

showed clustering of alternative splicing events by tissue type, and further revealed that tissue-specific programmes of transcription

and alternative splicing operate on different subsets of genes. A direct comparison also showed that computational prediction of

tissue-specific alternative splicing based on ESTs and cDNAs performed poorly compared with the alternative splicing microarray

and RT-PCR.

From: Matlin et al. (2005), Nature Rev Mol Cell Biol, 6: 386.

RNA-Seq (NGS)

Figure 1 | Frequency and relative abundance of alternative splicing isoforms in human

genes.

a, mRNA-Seq reads mapping to a portion of the SLC25A3 gene locus. The number of

mapped reads starting at each nucleotide position is displayed (log10) for the tissues listed

at the right. Arcs represent junctions detected by splice junction reads.

Bottom: exon/intron structures of representative transcripts containing mutually exclusive

exons 3A and 3B (GenBank accession numbers shown at the right).

b, Mean fraction of multi-exon genes with detected alternative splicing in bins of 500

genes, grouped by total read count per gene. A gene was considered as alternatively

spliced if splice junction reads joining the same 5’ splice site (5’SS) to different 3’ splice

sites (3’SS) (with at least two independently mapping reads supporting each junction), or

joining the same 3’SS to different 5’SS, were observed. The true extent of alternative

splicing was estimated from the upper asymptote of the best-fit sigmoid curve (red

curve). Circles show the fraction of alternatively spliced genes.

«Pure» alternative splicing

Figure 3

Types of alternative splicing.

In all five examples of alternative

splicing, constitutive exons are

shown in red and alternatively

spliced regions in green, introns are

represented by solid lines, and

dashed lines indicate splicing

activities. Relative abundance of

alternative splicing events that are

conserved between human and

mouse transcriptomes are shown

above each example (in % of total

alternative splicing events).

From: Ast G. (2004)

Nature Rev Genetics 5: 773.

Note that the indicated percentages derive from

older studies and are slightly different from

those demonstrated by recent, RNA-Seq based

evaluations

Figure 2 | Pervasive tissue-specific regulation of alternative mRNA isoforms. Rows represent the eight

different alternative transcript event types diagrammed. Mapped reads supporting expression of upper

isoform, lower isoform or both isoforms are shown in blue, red and grey, respectively. Columns 1–4

show the numbers of events of each type: (1) supported by cDNA and/or EST data; (2) with ≥ 1 isoform

supported by mRNA-Seq reads; (3) with both isoforms supported by reads; and (4) events detected as

tissue regulated (Fisher’s exact test) at an FDR of 5% (assuming negligible technical variation).

Columns 5 and 6 show: (5) the observed percentage of events with both isoforms detected that were

observed to be tissue-regulated; and (6) the estimated true percentage of tissue-regulated isoforms

after correction for power to detect tissue bias (Supplementary Fig. 6) and for the FDR. For some

event types, ‘common reads’ (grey bars) were used in lieu of (for tandem 39UTR events) or in

addition to ‘exclusion’ reads for detection of changes in isoform levels between tissues.

Note that Aa use the following definition for “tissue-specific”: at least 10% variation in isoforms.

Il progetto ENCODE ha mostrato che la

maggior parte dei geni umani dà

origine a trascritti plurimi, utilizzando:

• Siti di inizio alternativi

• Ampie variazioni nel quadro di

splicing

• 3’ alternativi

Il numero medio tendenziale sarebbe

tra 9 e 12 trascritti.

Figure 1 from Licatalosi et al., 2010

Some genes display “alternative promoters”

Proximal

promoter

Distal

promoter

5’

3’

1

2

Sometimes an exon is present between the two promoters

alternative parts

5’

3’

1

2

Coding or

noncoding

exon

If an acceptor site and a donor site are present

This is different from the story of multiple TSS

Unique TSS

5’

5’

3’

1

3’

1

Multiple TSS

Other genes possess “alternative polyadenylation sites”

Distal pA

site

Proximal pA

site

5’

3’

1

stop

stop

Coding or

noncoding

exon

How is Alternative Splicing Regulated ??

Costitutivo:

snRNP (U1,U2)

Siti di splicing

«conservati»

Alternativo:

elementi cis

(ESE, ESS, ISE,

ISS) riconosciuti

da SR, hnRNP,

Attivatori,

Repressori

Basics of the mechanisms of alternative splicing. (a) The architecture of a pre-mRNA and the important cis-acting

sequence elements that direct the splicing reaction. The consensus sequences for the 50 splice site, branchpoint and 3’

splice site for human introns is shown. (b) Schematic diagram of the sequences and proteins involved in regulating

alternative splicing. Four types of regulatory sequences are known: intronic splicing enhancers (ISEs), intronic splicing

silencers (ISSs), exonic splicing enhancers (ESEs) and exonic splicing silencers (ESSs). The enhancer elements are

recognized by activator proteins. Within exons, these activators are most commonly members of the SR protein family.

The silencer elements are bound by repressor proteins. Within exons, these repressors tend to be members of the

hnRNP protein family. Regardless of their binding location, activators tend to enhance the binding of spliceosomal

components to the regulated splice site while repressors tend to inhibit binding or function of the spliceosomal

components.

From: McManus & Graveley, COGD, 2011

Pervasive Transcriptome

RNA-Seq is used both for quantitative and qualitative evaluation of transcriptomes

Read mapping

Quantitative (measuring gene expression)

In this case, reads are mapped to a reference «transcriptome»,

then the number of reads for each known RNA is counted to

obtain a table of expression or a density graph.

Qualitative:

discovering

• new RNA transcripts

• new exon-exon junctions (i.e. alternative splicing forms)

• aberrant transcripts and splicing forms

•new RNA forms (e.g. circular RNA)

Experiments published to date using RNA-Seq

show extensive «pervasive» transcription of genomes

with more than 20,000 NONCODING RNA transcripts (human)

Noncoding are high percentage qualitatively

low percentage quantitatively

Nota: i numeri sono un po’

diversi da quelli che

successivamente presenterà

ENCODE. La differenza è

dovuta al numero di

esperimenti considerati, che

qui sono relativamente pochi

(2007-2008).

Ponting & Belgard, 2009

ENCODE

Today: many RNA-Seq experiments on tissues, cell lines published.

ENCODE reports results from 15 cell lines

RNA-Seq from either «cytoplasmic» or «nuclear» fractions, poly(A+) or (A-) RNA

62% of genomic bases are represented in long RNA transcripts (>200nt)

only 5.5% map to GENECODE exons

only 31% were classified «intergenic»

CAGE analysis: 62,403 TSS

Nuclear to cytoplasmatic analysis showed many transcripts processed

to give short RNA (<200)

Very elevated prevalence of Alternative splicing

Each gene show several transcripts (6-9 per gene, depending on

classification) plateauing at 12.

Short noncoding

snRNA

small U-RNA components of spliceosome particles

snoRNA

small RNA that guide chemical modifications to other RNAs

micro-RNA (miRNA)

single-stranded 21-24 nt post-transcriptional regulators

siRNA

double-stranded 21-25 bp , silencing RNA various pathways

piRNA

26-31 nt involved in transcriptional silencing (transposons)

sRNA

various transcription associated small RNA, unknown

Long noncoding (15-20,000 transcripts identified)

The simplest classification of long ncRNAs is based on their loci of origin.

• Antisense transcripts

Transcribed in antisense of coding RNA

• Intronic transcripts (sense or a/s)

Spanning introns

• Divergent transcripts

starting from promoters in opposite

direction

• Long intergenic transcripts

Transcript in gene-desert regions

• e-RNA

In either direction, starting from active

enhancers

No class-specific function identified.

Sporadic functions described:

• Transcriptional regulators, connecting activators or repressors

• Silencing, by acting as scaffold for chromatin modifying enzymes

• «Sponges» for micro RNA

• Translational regulators

Dal punto di vista della regolazione, le due classi più nuove e

più interessanti sono:

micro RNA

lnc RNA

Nella seconda parte di regolazione

![mutazioni genetiche [al DNA] effetti evolutivi [fetali] effetti tardivi](http://s1.studylibit.com/store/data/004205334_1-d8ada56ee9f5184276979f04a9a248a9-300x300.png)