Genomi 8

The

Minimal Genome

The Minimal Genome project

In a 1999 study among M. genitalium and Mycoplasma pneumoniae, the Craig Venter team mapped around 2,200 transposon insertion sites

and identified 130 putative non-essentials genes in M. genitalium protein coding genes or M. pneumoniae orthologs of M. genitalium genes. In

their experiment they grew a set of Tn4001 transformed cells for many weeks and isolated the genomic DNA from these mixture of mutants.

Amplicons were sequenced to detect the transposon insertion sites in mycoplasma genomes. Genes that contained the transposon insertions

were hypothetical proteins or proteins considered non-essential.

Meanwhile, during this process some of the disruptive genes that at first were considered non-essential, after more analyses turned out be

essential. The reason for this error could have been due to genes being tolerant to the transposon insertions and thus not being disrupted; cells

may have contained two copies of the same gene; or gene product was supplied by more than one cell in those mixed pools of mutants.

Insertion of transposon in a gene meant it was disturbed, hence non-essential, but because they did not confirm the absence of gene products

they mistook all disruptive genes as non-essential genes.

The same study of 1999 was later expanded and the updated results were then published in 2005. Some of the disruptive genes though to be

essential were isoleucyl and tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases (MG345 and MG455), DNA replication gene dnaA (MG469), and DNA polymerase III

subunit a (MG261). The way they improved this study was by isolating and characterizing M. genitalium Tn4001 insertions in each colony one

by one. The individual analyses of each colony showed more results and estimates of essential genes necessary for life. The key improvement

they made in this study was isolating and characterizing individual transposon mutants. Previously, they isolated many colonies containing a

mixture of mutants. The filter cloning approach helped in separating the mixtures of mutants.

Now, they claim completely different sets of non-essential genes. The 130 non-essential genes claimed at first have now reduced to 67. Of the

remaining 63 genes 26 genes were only disrupted in M. pneumoniae which means that some M. genitalium orthologs of non-essential M.

pneumoniae genes were actually essential.

They have now fully identified almost all of the non-essential genes in M. genitalium, the number of gene disruptions based on colonies

analyzed reached a plateau as function and they claim a total of 100 non-essential genes out of the 482 protein coding genes in M. genitalium

The ultimate result of this project has now come down to constructing a synthetic organism, Mycoplasma laboratorium based on the 387

protein coding region and 43 structural RNA genes found in M. genitalium

1. Determinazione del genoma minimale

Global Transposon Mutagenesis and a

Minimal Mycoplasma Genome (1999)

Mycoplasma genitalium with 517 genes (480 protein-coding genes plus 37 genes for RNA species) has

the smallest gene complement of any independently replicating cell so far identified.

Global transposon mutagenesis was used to identify nonessential genes in an effort to learn whether

the naturally occurring gene complement is a true minimal genome under laboratory growth

conditions.

The positions of 2209 transposon insertions in the completely sequenced genomes of M. genitalium

and its close relative M. pneumoniae were determined by sequencing across the junction of the

transposon and the genomic DNA. These junctions defined 1354 distinct sites of insertion that were

not lethal.

The analysis suggests that 265 to 350 of the 480 protein-coding genes of M. genitalium are essential

under laboratory growth conditions, including about 100 genes of unknown function.

I geni essenziali sono conservati filogeneticamente

1996:

Sequenziati i genomi di Haemophilus influenzae e Mycoplasma genitalium, molto

diversi tra loro, e prima proposta di genoma minimo teorico di 256 geni, basato

sul confronto dei geni ortologhi presenti in entrambi i microrganismi (geni

essenziali devono essere conservati).

Haemophilus influenzae

Mycoplasma genitalium

Microorganismi utilizzati per determinare il

genoma minimale

ENTRAMBI COMPLETAMENTE SEQUENZIATI

M pneumoniae è il parente più vicino a M genitalium

Mycoplasma

genitalium:

580 kb (517 geni)

480 geni codificanti proteine

37 geni codificanti per RNA

considerato il più piccolo genoma cellulare

Mycoplasma

pneumoniae:

816 kb (236 kb in più di M. genitalium)

possiede i geni ortologhi di tutti i 480 geni di M.

genitalium + 197 geni addizionali

Le proteine codificate dai geni ortologhi hanno un’ omologia soltanto del 65%:

distanza evolutiva elevata

Microorganismi utilizzati per determinare il

genoma minimale

•

The smallest known cellular genome is that of Mycoplasma genitalium, which is only 580 kb. This

genome has been completely sequenced, and analysis of the sequence revealed 480 protein-coding

genes plus 37 genes for RNA species.

•

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is the closest known relative of M. genitalium, with a genome size of 816

kb, 236 kb larger than that of M. genitalium

Comparison of the two genomes indicates that M. pneumoniae includes orthologs of virtually every

one of the 480 M. genitalium protein-coding genes, plus an additional 197 genes. There is a substantial

evolutionary distance between orthologous genes in the two species, which share an average of only

65% amino acid sequence identity.

“The existence of these two species with

overlapping gene content provided an

experimental paradigm to test whether the 480

protein-coding genes shared between the

species were already close to a minimal gene

set. We applied transposon mutagenesis to

these completely sequenced genomes, which

permitted precise localization of insertion sites

with respect to each of the coding sequences.”

Come determinare se un gene é

essenziale?

Si inattivano i geni tramite mutagenesi traspositiva

(transposon mutagenesis)

Se il batterio trasformato cresce in coltura il gene non è

considerato essenziale (anche se potrebbe esserlo ->

famiglie geniche)

I geni nei quali non si riscontra inserzione sono considerati

essenziali

Transposon mutagenesis

Trasposone Tn4001 all’interno del plasmide di E.

coli plSM2062

Trasformazione tramite elettroporazione

M. genitalium e M. pneumoniae

Il plasmide contiene la resistenza alla gentamicina

-> in terreno con antibiotico crescono solo i batteri

che hanno inglobato il plasmide e di conseguenza

il trasposone

Estrazione del DNA, digestione, circolarizzazione,

IPCR, digestione, clonaggio in pUC18, creazione di

una libreria di giunzioni tra trasposone e DNA

genomico

Sequenziamento

Identificazione della regione dove si è inserito il

trasposone

in

Risultato della mutagenesi traspositiva

Analisi di 2209 inserzioni ha rivelato 1354 siti di inserzione diversi, equalmente suddivisi fra I due

microrganismi. Preferenza di inserzione in sequenze non codificanti (71% M. genitalium e 61% in M.

pneumoniae). This represents a substantial preference for intergenic insertion because coding sequence

constitutes 85% of the M. genitalium genome and 89% of the M. pneumoniae genome, and is consistent with the

idea that intergenic sequences are less critical than protein-coding regions for viability

Inserzioni in 140 geni in M. genitalium e 179 geni in M. pneumoniae

Inserzioni in M. pneumoniae soprattutto all’interno di geni specie-specifici. This result supports our

assumption that the M. pneumoniae–specific portion of the genome is fully dispensable

Consistente assenza di inserzioni in regioni considerate a priori essenziali. The conspicuous absence of

transposon insertions into certain regions expected to be essential - for example, the region containing a cluster of

ribosomal genes - provides additional support for the validity of transposon mutagenesis as an assay for

dispensability

Quando considerare distruttiva un'inserzione:

Inserzioni all’estremità 3’ possono

rimuovere solo un terminale COOH non

essenziale

Inserzioni all’estremità 5’ non sempre

distruggono la funzione genica

Un’inserzione è considerata distruttiva se avviene entro l’80% della sequenza dall’estremità 5’, ma a

valle del nono nucleotide della regione codificante la proteina. This criterion eliminates events in which the 5’

end of the gene may actually be intact because of duplication of a short sequence at the target site. Similarly, an

insertion near the 5’ end of a gene may not always destroy gene function. Transposon Tn4001 contains an outwarddirected promoter that could drive transcription of flanking chromosomal DNA, leading to translation if an internal

start site is located nearby downstream

Quindi i geni con inserzioni distruttive

sono:

66% di M. genitalium

84% di M. pneumoniae

La differenza è da attribuirsi alla più alta

proporzione di geni non-essenziali di

M.pneumoniae

The majority of M. genitalium orthologs that have disruptive insertions are absent from the third fully sequenced

mycoplasma genome, Ureaplasma urealyticum, consistent with the idea that they are not essential.

Dopo aver stabilito che i geni M. pneumoniae specifici non sono

indispensabili, si è cercato di trovare il numero dei geni

essenziali all’interno degli ortologhi

Dei 480 geni ortologhi, che M. genitalium e M. pneumoniae hanno

in comune, sono stati trovati 129 geni con inserzione

non sono essenziali per la vita in laboratorio

We have also estimated the number of nonessential genes to be between 180 to 215 under the

assumption that the number of sites hit per gene follows a Poisson distribution. These larger

estimates fit reasonably with the observed proportion of orthologs hit in both species. Therefore, on

the basis of our highest and lowest estimates for nonessential genes, we estimate that the number

of essential mycoplasma protein-coding genes is between 265 and 350.

SPERIMENTALMENTE:

480 (ortologhi) – 129 (geni non indispensabili)

351 GENI ESSENZIALI

TEORICAMENTE:

480 (ortologhi) – 180/215 (geni non indispensabili)

265-350 GENI ESSENZIALI

The 351 M. genitalium orthologs for which we have not yet identified a disruptive insertion constitute a first

approximation to the true set of essential mycoplasma genes. From our estimate, we predict that at least 3/4 of the

351 undisrupted genes are essential. We also expect that most undisrupted genes within each functional class

represent essential genes. Examination of the gene disruption data, organized by functional role, reveals that all

functional classes of genes are not equally mutable under the selective growth conditions used in this study, which

suggests that the genes are closer to a minimal set for some cellular functions than for others

Pathway essenziali

Nessuna inserzione ritrovata in:

Geni della glicolisi

(10 geni)

Geni delle pompe

protoniche (8 geni)

Si è visto che:

sono essenziali anche 111 geni di qui non si conosce la

funzione (unknown), che andranno caratterizzati in futuro

geni che si ipotizzavano essenziali come le lipoproteine non lo

sono

esse servono per l’infezione della cellula ospite, quindi

sono essenziali per la vita in natura, ma non per quella in

laboratorio

I rompicapo

Trasportatori ABC

trasportano molecole all’interno della cellula sfruttando

l’idrolisi di ATP

3 subunità:

ATP-binding

Permeasi

Ligand-binding

ATP-binding

sono le più rappresentate nel genoma ma

alcune sembrano essere “orfane” dato che

le altre due subunità sono meno numerose

The fact that only 25% of the ATP-binding subunits in our data set tolerate insertions suggests that

at least some of these orphan subunits do serve an essential function within the cell -> Analysis of

the M. genitalium genomic sequence data with less stringent searching parameters aimed at finding

partners of the orphan specificity subunits, led to the identification of potential transport partners

Trasportatore del fosfato

è fondamentale per la vita

Delle 3 subunità, 2 possono essere distrutte

quindi non è essenziale...PERCHÉ?

This finding forces us to consider the possibility that some as yet undefined transport

system exists in these mycoplasmas that can compensate for mutations in the

putative phosphate transporter

Nei due genomi sono presenti due omologhi di DNA pol III oltre che a recA e uvrA

uno dei due omologhi di DNA pol III

Sono presenti inserzioni in

recA

uvrA

It is almost certain that cells bearing such gene disruptions in nature would be quickly

selected against. Although it is difficult to address this idea quantitatively, it poses a

relevant question for consideration when attempting to define a minimal gene set for

cellular life.

Osservate alcune inserzioni (circa l’1% di tutte le inserzioni mappate) in

geni ritenuti essenziali

l’annotazione di geni in base alla similarità di sequenza è sbagliata

le inserzioni non hanno distrutto i geni (poco probabile)

i geni sono stati duplicati (some cells might contain a functional duplicate copy of a gene

in addition to the disrupted gene)

le cellule incorporano enzimi dal mezzo

cross-feeding

(one strain shows superior growth on the limiting primary resource (glucose)

but degrades it only partially and excretes product (e.g., acetate) that is used as secondary

substrate by another strain

Conclusive proof of the dispensability of any specific gene requires cloning and

detailed characterization of a pure population carrying the disrupted gene.

Conclusioni della mutagenesi traspositiva

Preferenza di inserzione in sequenze non codificanti (71% M. genitalium e 61%

in M. pneumoniae), di conseguenza le sequenze intergeniche non sono necessarie per

la vita in senso stretto

Inserzioni in 140 geni (M. genitalium) e 179 (M. pneumoniae)

Inserzioni in M. pneumoniae soprattutto all’interno di geni specie-specifici

condivisi o con bassa % di identità, di conseguenza la porzione specifica

di M. pneumoniae non è indispensabile

NON

Consistente assenza di inserzioni in regioni considerate a priori essenziali, di

conseguenza si è visto che la mutagenesi traspositiva è un buon metodo di

analisi dei geni essenziali (genoma minimo)

Sebbene M. genitalium contenga il più piccolo numero di geni, molti di essi non sono

essenziali per la vita in laboratorio

Dei 111 geni a funzione ignota ed essenziali molti sono Mycoplasma specifici

2. Determinazione del genoma minimale

Essential genes of a minimal bacterium

(2006)

Mycoplasma genitalium has the smallest genome of any organism that can be grown in pure

culture. It has a minimal metabolism and little genomic redundancy. Consequently, its genome is

expected to be a close approximation to the minimal set of genes needed to sustain bacterial

life.

Using global transposon mutagenesis, we isolated and characterized gene disruption mutants

for 100 different nonessential protein-coding genes. None of the 43 RNA-coding genes were

disrupted. Herein, we identify 382 of the 482 M. genitalium protein-coding genes as essential,

plus five sets of disrupted genes that encode proteins with potentially redundant essential

functions, such as phosphate transport. Genes encoding proteins of unknown function

constitute 28% of the essential protein-coding genes set. Disruption of some genes accelerated

M. genitalium growth.

“In 1999 we reported the use of global transposon mutagenesis to experimentally determine the genes

not essential for laboratory growth of M. genitalium

In that report we identified 130 putatively nonessential M. genitalium protein-coding genes or M.

pneumoniae orthologs of M. genitalium genes. We estimated that 265–350 of the protein-coding

genes of M. Genitalium are essential under laboratory growth conditions.

However, proof of gene dispensability requires isolation and characterization of pure clonal

populations, which we did not do. We grew Tn4001- transformed cells in mixed pools for several weeks

and then isolated genomic DNA from those mixtures of mutants.

Herein, we report an expanded study in which we have isolated and characterized M. genitalium

Tn4001 insertion mutants that were present in individual colonies picked from agar plates. From this

analysis, we made a more thorough estimate of the number of genes essential for growth of this

minimalist bacterium.”

To exclude the possibility that gene disruptions were the result of a transposon insertion in one copy

of a duplicated gene, we used PCR to detect genes lacking the insertion. These PCRs showed us that

almost all of the colonies contained both disrupted and WT versions of the genes identified as

having the Tn4001. Further analysis using quantitative PCR showed that most colonies were

mixtures of two or more mutants

In total, we analyzed 3,321 M. genitalium transposon insertion mutant primary colonies and

subcolonies to determine the locations of Tn4001tet inserts

Of the successfully sequenced subcolonies, 59% revealed a transposon insertion at a different site

from that in the parental primary colony

We mapped a total of 2,462 different transposon insertion sites on the genome. 84% of the

mutations were in protein-coding genes. No rRNA, tRNA, or structural RNA genes contained

insertions.

To address our central question of which M. genitalium genes were not essential for growth in SP4 (a

rich laboratory medium), we used the same criteria to designate a gene disruption as in our previous

study. We considered transposon insertions disruptive if they were after the first three codons and

before the 3-most 20% of the coding sequence of a gene.

After subcloning, we were able to isolate gene disruption mutant colonies for 100 different disrupted

M. genitalium genes

48 of the 100 disrupted genes were either hypothetical proteins or proteins of unknown function,

and there was an absence of disruptions in genes and regions expected to be universally essential

Several mutants manifested remarkable phenotypes. Although some of the mutants grew slowly,

mutants in lactate malate dehydrogenase (MG460) and conserved hypothetical proteins MG414 and

MG415 mutants had doubling times up to 20% faster than WT M. genitalium.

Mutants in MG185, which encodes a putative lipoprotein, floated rather than adhering to plastic as do

WT cells. Cells with transposon insertions in the transketolase gene (MG066), which encodes a

membrane protein and pentose phosphate pathway enzyme, grew in chains of clumped cells rather

than in the monolayers characteristic of WT M. genitalium

Of the successfully sequenced subcolonies, 59% revealed a transposon insertion at a different site

from that in the parental primary colon. However, the rate of accumulation of new insertion sites

dropped after our first 600 sequences from independent colonies, indicating that we were

approaching saturation mutagenesis of all nonlethal insertion sites

We believe that we have identified nearly all of the nonessential genes in M. genitalium

because, as shown in Fig. 1, the number of new gene disruptions reached a plateau as a function

of the number of colonies analyzed.

Mostly, we mutated the kinds of genes we expected to be nonessential: 48 of the 100 disrupted

genes were either hypothetical proteins or proteins of unknown function, and there was an

absence of disruptions in genes and regions expected to be universally essential.

Still, many disrupted genes encoded proteins that one might think would be important because of

the roles they play in metabolism or information storage and processing.

None of the genes encoding the key enzymes of DNA replication were disrupted.

However, we isolated mutants in other DNA metabolism genes that were expendable for the

duration of our experiment, but might be necessary to maintain the M. genitalium genome over

periods much longer than this experiment, like the genes involved in recombination and DNA repair.

Metabolic pathways and substrate transport mechanisms encoded by M. genitalium. Metabolic products are colored

red, and mycoplasma proteins are black. White letters on black boxes mark nonessential functions or proteins based on our current

gene disruption study. Question marks denote enzymes or transporters not identified that would be necessary to complete pathways,

and those missing enzyme and transporter names are colored green. Transporters are colored according to their substrates: yellow,

cations; green, anions and amino acids; orange, carbohydrates; purple, multidrug and metabolic end product efflux. The arrows

indicate the predicted direction of substrate transport. The ABC type transporters are drawn as follows: rectangle, substrate-binding

protein; diamonds, membrane-spanning permeases; circles, ATP-binding subunits.

Under our laboratory conditions, we identified 100 nonessential genes. Logically, the

remaining 382 M. genitalium proteincoding genes, 3 phosphate transporter genes,

and 43 RNAcoding genes presumably constitute the set of genes essential for growth

of this minimal cell

Accordingly, these families’ functions may be essential, and we expanded our

projection of the set of essential genes to 387 to include them. This is a significantly

greater number of essential genes than the 265–350 predicted in our previous study

of M. genitalium

These data suggest that a genome constructed to encode 387 protein-coding and

43 structural RNA genes could sustain a viable synthetic cell, a Mycoplasma

laboratorium

3. TRASFERIMENTO DI UN GENOMA

COMPLETO DA UNA SPECIE BATTERICA AD

UN’ALTRA

Genome Transplantation in Bacteria:

Changing One Species to Another

As a step toward propagation of synthetic genomes, the genome of a bacterial cell was

completely replaced with one from another species by transplanting a whole genome as

naked DNA.

Intact genomic DNA from Mycoplasma mycoides, virtually free of protein, was

transplanted into Mycoplasma capricolum cells by polyethylene glycol–mediated

transformation. Cells selected for tetracycline resistance, carried by the M. mycoides

chromosome, contain the complete donor genome and are free of detectable recipient

genomic sequences.

These cells that result from genome transplantation are phenotypically identical to the

M. mycoides LC donor strain as judged by several criteria.

“GENOME TRANSPLANTATION”

un intero genoma batterico da una specie è “trapiantato”

(trasformazione PEG mediata) in un'altra specie batterica

il ricevente mostra genotipo e fenotipo del donatore

il ricevente perde il proprio genoma

non c'è ricombinazione tra i cromosomi in entrata e in uscita

cambio di una specie batterica in un'altra

Premesse

1994: Osvald Avery scopre che il DNA nudo può essere incorporato

da P. pneumoniae

2005: Itaya et al. primo trasferimento di un genoma quasi completo

da Synechocystis PCC6803 a Bacillus subtilis, ma riscontrati

diversi problemi a livello di silenziamento genico

2007: R. A. Holt et al. trasferiscono un intero genoma da

Haemophilus influenzae a Escherichia coli con l’utilizzo di BAC.

Sono stati riscontrati problemi di incompatibilità tra i due

genomi.

Perché é stato scelto il Mycoplasma?

uso di UGA per codificare

triptofano (invece di un codone

di stop)-> no proteine prodotte

in E. coli durante il clonaggio

piccoli genomi

la mancanza totale di una parete

cellulare lo rende più simile ad una

cellula eucariotica e rende più semplice

l’inserimento di DNA

presenta un accrescimento rapido

(divisione ogni 80-100 min)

Specie usate per il “trapianto”:

1. Mycoplasma mycoides sottospecie mycoides LC (large colony) ceppo GM12

come cellule donatrici. Presenta resistenza alla tetraciclina e il gene lac-Z

2. Mycoplasma capricolum sottospecie capricolum, ceppo California kid come

cellule riceventi

I genomi dei due microrganismi sono stati sequenziati e comparati:

91.5% identità nucleotidica

We found that 76.4% of the 1,083,241-bp draft sequence of the M.

mycoides LC genome could be mapped to the 1,010,023-bp M.

capricolum genome, and this content matched on average at 91.5%

nucleotide identity.

The remaining ~24% of the M. mycoides LC genome contains a

large number of insertion sequences not found in M. capricolum.

Tre fasi principali del “trapianto”:

1. Isolamento del genoma intatto del donatore da M. mycoides LC

2. Preparazione delle cellule riceventi di M. capricolum

3. Inserimento del genoma isolato nelle cellule riceventi

Plasmidi di M. mycoides LC con origine

del complesso di replicazione (ORC)

M. mycoides

M. capricolum

Plasmidi di M. capricolum LC con origine

del complesso di replicazione (ORC)

We chose our donor and recipient cells for genome transplantation on the basis of our observation that plasmids

containing a M. mycoides LC origin of replication complex (ORC) can be established in M. capricolum, whereas

plasmids with an M. capricolum ORC cannot be established in M. mycoides LC

Preparazione delle cellule donatrici:

M. mycoides

1. Ridurre al massimo le manipolazioni

del genoma per non romperlo

Cellule messe in blocchi di agarosio,

trattate con detergenti ed enzimi

proteolitici per ottenere DNA purificato

2. Inserimento delle cellule nei plug di agarosio

Interessa avere DNA circolare:

usata elettroforesi a campo pulsato (PFGE) per separare il DNA

circolare (intrappolato nel plug) da quello danneggiato

(lineare). Circular DNA is indeed trapped into the agarose. Cirlces become hooked on

threads of agarose fibers and become frozen in their forward motion.

Ulteriori prove per confermare di avere solo DNA circolare:

trattamento con nucleasi

analisi dei plug (verifica della purezza del DNA)

spettrometria di massa (verifica della purezza del DNA)

3. Liberazione del DNA dai plug

Trasfrormazione di M. capricolum

1. Trattamento delle cellule di M. capricolum con PEG per la trasformazione

in presenza del genoma di M. mycoides,

3. Recupero della cellule e semina su piastre contenenti tetraciclina e X-gal.

(il batterio donatore ha il gene di resistenza all’antibiotico e il gene lac-Z)

Cosa ci si aspetta???

Dato che il genoma donatore possiede i geni per la resistenza alla

tetraciclina e l’operone lac, la cellula ricevente, che ha assunto il

genoma donatore, possiede resistenza all’antibiotico e assume

colorazione blu in presenza di X-gal

Cosa si é osservato?

Si sono osservate colonie resistenti all’antibiotico e blu in un primo tempo,

successivamente si è notata la comparsa di

piccole colonie bianche

Si pensa che per un breve periodo di tempo la cellula mantiene entrambi i

genomi, perché quello del ricevente non è stato tolto: le colonie resistenti e

bianche devono derivare da ricombinazione

The plates were incubated at 37°C until large blue colonies, putatively M. mycoides LC,

formed after ~3 days.

Sometimes, after ~10 days smaller M. capricolum colonies, both blue and white, were

visible.

Thus, all of these colonies were tetracycline-resistant, as evidenced by their surviving the

antibiotic selection, and only some expressed b-galactosidase. These colonies might be the

result of recombination. We observed that these colonies appeared after almost twice as

many days as it took for the transplants to become visible

The blue, tetracycline-resistant colonies resulting from M. mycoides LC genome

transplantation were to be expected if the genome was successfully transplanted.

However, colonies with that phenotype could also result from recombination of a

fragment of M. mycoides LC genomic DNA containing the tetM and lacZ genes into the M.

capricolum genome.

To rule out recombination, we examined the phenotype and genotype of the

transplanted clones.

Analisi genotipiche

PCR con primer specie-specifici

Analisi SOUTHERN BLOT di

donatore, ricevente e “trapiantati”

SEQUENZIAMENTO di un

campione delle librerie

genomiche totali di uno dei due

cloni “trapiantati”

I risultati non escludono che la

ricombinazione non avvenga

Il 54% dei trapiantati hanno

profilo identico al wild-type

Analisi di 1300 reads di ciascun clone

(2), e tutte si appaiono con la

sequenza di M. mycoides

Le analisi genotipiche hanno confermato il

corretto inserimento del genoma del donatore

nel ricevente, ma lasciano aperta l’ipotesi di

una possibile ricombinazione tra i due genomi

Analisi fenotipica

COLONY WESTERN BLOT su donatore e ricevente e

quattro diversi cloni “trapiantati” utilizzando degli

anticorpi specifici per gli antigeni di superficie di

M. capricolum e successivamente per M. mycoides

Nei blot dei “trapiantati” l’anticorpo specifico per

l'antigene di superficie di M. mycoides ibrida con la

stessa intensità che si osserva nel blot del wild-type.

Invece l’anticorpo specifico per l' antigene di

superficie di M. capricolum non ibrida nei blot dei

“trapiantati”

E' stata effettuata un'analisi proteomica consistente in un'

ELETTROFORESI BIDIMENSIONALE su lisati cellulari (proteine).

Spot di M. mycoides IDENTICI agli spot dei “trapiantati”

Spot di M. capricolum MOLTO DIVERSI (più del 50%) dagli spot dei “trapiantati”

Questi risultati sono stati ulteriormente confermati dalle analisi MALDI-MS

(spettrometria di massa a dessorbimento-ionizzazione laser assistito da matrice)

Conclusioni del trapianto di un genoma

batterico

Questi dati hanno dimostrato che è possibile il “trapianto” di

interi genomi da una specie ad un’altra. La progenie risultante è

genotipicamente e fenotipicamente uguale al donatore

Si pensa che subito dopo il “trapianto” gli organismi portino entrambi

i genomi

Negli esperimenti più efficienti, solo 1 cellula ricevente

su ~ 150,000 è stata “trapiantata”; questa bassa

efficienza non ha permesso di dimostrare un

mosaicismo momentaneo.

Il “trapianto” di genoma funziona per le specie scelte

SONO FILOGENETICAMENTE

MOLTO SIMILI

MA PER LE ALTRE SPECIE FUNZIONERA‘?

“These data demonstrate the transplantation of whole genomes from one species to

another such that the resulting progeny are the same species as the donor genome.

However, they do not explain the mechanism of the transplant.”

Non è una trasformazione naturale del DNA

il “trapianto” del genoma in questione non richiede la

ricombinazione

il DNA che si inserisce è circolare

non è stata identificata la presenza di geni di uptake per il

DNA nel genoma di M. capricolum

In assenza di trattamenti con detergenti o proteasi K, i nucleoidi

delle cellule di M. mycoides LC non producono “trapiantati”.

Data l’improbabilità di un evento naturale come il libero fluttuare

di genomi batterici, il “trapianto” di genoma potrebbe essere un

fenomeno solo da laboratorio

In ogni caso, E' STATA MESSA A PUNTO UNA FORMA DI

TRASFERIMENTO DI DNA BATTERICO CHE PERMETTE ALLE

CELLULE RICEVENTI DI FUNGERE DA PIATTAFORME PER LA

PRODUZIONE DI NUOVE SPECIE con l’uso di genomi naturali

modificati o sintetici

4. SINTESI CHIMICA, ASSEMBLAGGIO E

CLONAGGIO DI UN GENOMA

Complete Chemical Synthesis, Assembly, and

Cloning of a Mycoplasma genitalium Genome

A 582,970–base pair Mycoplasma genitalium genome has been synthesized.

This synthetic genome, named M. genitalium JCVI-1.0, contains all the genes of wild-type M.

genitalium G37 except MG408, which was disrupted by an antibiotic marker to block

pathogenicity and to allow for selection.

To identify the genome as synthetic, “watermarks” were inserted at intergenic sites known

to tolerate transposon insertions. Overlapping “cassettes” of 5 to 7 kilobases (kb),

assembled from chemically synthesized oligonucleotides, were joined by in vitro

recombination to produce intermediate assemblies of approximately 24 kb, 72 kb (“1/8

genome”), and 144 kb (“1/4 genome”), which were all cloned as bacterial artificial

chromosomes in Escherichia coli. Most of these intermediate clones were sequenced, and

clones of all four 1/4 genomes with the correct sequence were identified. The complete

synthetic genome was assembled by transformation-associated recombination cloning in

the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, then isolated and sequenced. A clone with the correct

sequence was identified.

Mycoplasma genitalium

batterio con il genoma più piccolo (580,076bp)

485 geni codificanti proteine di cui 100 non essenziali

non si sa quali dei 100 sono non essenziali simultaneamente

We proposed that one approach to this question would be to produce reduced

genomes by chemical synthesis and introduce them into cells to test their

capacity to provide the essential genetic functions for life

“The largest previously published synthetic

DNA that we are aware of is a 32-kb polyketide

gene cluster»

Come costruire il genoma sintetico?

1. Divisione del genoma in 101 cassette di 5-7 Kb tramite:

sintesi

sequenziamento

ligazione

2. Inserimento di sequenze watermark nelle cassette 14-29-3955 e 61 → corte sequenze inserite in siti intergenici,

utilizzate per distinguere il genoma sintetico da quello nativo

3. Inserimento di 2514 bp (resistenza aminoglicosilica) nella cassetta 89,

all'interno gene MG408, allo scopo di perdere la patogenicità nei

mammiferi

4. Dimensione del genoma sintetico ottenuto (JVCI-1.0) è di 582,970 bp,

partendo da 580,076 bp (M. genitalium)

Le cassette:

Le cassette sono state sintetizzate dalla Blue Heron

Technology

ognuna contiene una o più geni completi

ogni cassetta termina con una sequenza che si

sovrappone alla successiva per poterle assemblare

la cassetta 101 si sovrappone alla 1 per formare una

struttura circolare

Fasi (5) di assemblaggio del genoma:

assemblaggio delle cassette in vitro e clonaggio in E. coli (A-B-C)

assemblaggio delle cassette in vivo e clonaggio in S. cerevisiae (D e E)

clonaggio in E. coli

clonaggio in S. cerevisiae

Assemblaggio in vitro e clonaggio in E. coli

Le cassette sono state recuperate dai rispettivi plasmidi e sottoposte alle

seguenti reazioni:

In seguito a digestione con

3’-esonucleasi, le cassette espongono

le estremità sovrapponibili

Le estremità si appaiano formando

una lunga molecola composta da 4

cassette

Il costrutto così ottenuto viene quindi

riparato con Taq-polimerasi e Taqligasi

PCR amplification was used to produce a

unique BAC vector for the cloning of each

assembly, with terminal overlaps to the ends

of the assembly.

Each PCR primer includes an overlap with

one end of the BAC, a Not I restriction site,

and an overlap with one end of the cassette

assembly.

The 3′ ends of the mixture of duplex vector and

cassette DNAs were then digested to expose the

overlap regions using T4 polymerase in the

absence of dNTPs.

The annealed joints were repaired using Taq

polymerase and Taq ligase

Because the M. genitalium JCVI-1.0 genome does not contain a Not I site, all of

the assemblies can be released intact from the BAC.

A questo punto, i BAC neo-sintetizzati vengono inseriti in E. coli per

la moltiplicazione.

Dopo la replicazione in E. coli si recupera il frammento d'interesse

mediante restrizione con NotI.

In questo modo sono state ottenute le 25 serie A

B-series assemblies were constructed from Not I–digested A-series clones

C-series assemblies were constructed from Not I–digested B-series

assemblies.

Assemblaggio in vivo e clonaggio in S. cerevisiae

Dato che si sospettava l’instabilità di grandi assemblaggi in E. coli, è stato

necessario passare in lievito utilizzando la tecnica TAR (Transformation

Associated Ricombination), che si basa sulla ricombinazione omologa

durante la co-trasformazione in sferoplasti di lievito.

Il vettore TAR è costituito da:

sequenza BAC

sequenza YAC

due 'ganci' alle due estremità che

subiscono una ricombinazione con le

regioni omologhe del gene d’interesse

circolarizzazione

All'interno del lievito riusciamo ad assemblare l'intero genoma

Estrazione del genoma sintetico di

M.genitalium dal lievito e verifica

della sua sequenza:

Analisi CHEF

Kb

DNA totale isolato in agarosio

Taglio selettivo del cromosoma sintetico

con NotI

Separazione del frammento sintetico

tramite elettroforesi

582.0

145.5

96.0

48.5

23.0

9.4

Sequenziamento del DNA del clone

sMgTARBAC37 con copertura 7x

6.6

4.4

Conclusioni della sintesi chimica, assemblaggio e clonaggio di un genoma

L’intero cromosoma di M. genitalium è stato progettato,

sintetizzato, assemblato e clonato in lievito

Il costrutto è formato da 104 oligonucleotidi lunghi 50

basi ciascuno; fino ad ora è la più grande molecola

sintetica a struttura nota ottenuta (582,970 bp)

L'efficacia della procedura in vitro è diminuita con

l'aumentare della dimensione degli assemblati, per cui

l’assemblaggio dei frammenti più grandi va effettuato

mediante ricombinazione in vivo

We are currently using a TARBAC vector to propagate the

synthetic chromosome in yeast.

We do not know whether this vector might interfere

with the production of viable cells by transplantation,

nor do we know whether the genomic location of the

vector could affect viability.

It may be necessary to alter the vector sequences or

even to excise the vector before transplantation.

In closing, we wonder whether use of the UGA codon to code for tryptophan in

mycoplasmas, rather than for termination as in the “universal” code, contributed

to our success in cloning the synthetic M. genitalium JCVI-1.0 genome.

This may make cloning in E. coli and other organisms less toxic because most M.

genitalium proteins will be truncated. If so, then it should be possible to synthesize

other genome constructions using this same code. The genome would then need to

be installed, for example, by transplantation, in a cytoplasm that can properly

translate the UGA to tryptophan. To generalize on this phenomenon, it might be

possible to use other codon changes as long as there is a receptive cytoplasm with

appropriate codon usage.

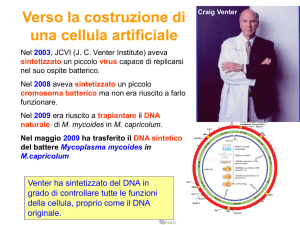

5. Creazione di una cellula batterica

controllata dal genoma sintetico

Creation of a Bacterial Cell Controlled by a

Chemically Synthesized Genome

Because M. genitalium has an extremely slow growth rate, we turned to two fastergrowing mycoplasma species, M. mycoides subspecies capri (GM12) as donor, and M.

capricolum subspecies capricolum (CK) as recipient.

The 1.08 Mb Mycoplasma mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 genome has been designed,

synthesised, and assembled starting from digitized genome sequence information

Then, the JCVI-syn1.0 genome has been transplantated into a M. capricolum recipient

cell to create new M. mycoides cells that are controlled only by the synthetic

chromosome.

The only DNA in the cells is the designed synthetic DNA sequence, including

“watermark” sequences and other designed gene deletions and polymorphisms, and

mutations acquired during the building process.

The new cells have expected phenotypic properties and are capable of continuous selfreplication.

Ostacoli iniziali

Metodo per estrarre il cromosoma intatto dal lievito

richiede

miglioramento

capire se è possibile “trapiantare” il cromosoma estratto da lievito in una

cellula batterica

verificare che la cellula batterica sia controllata esclusivamente dal genoma

sintetico

M. mycoides subspecies capri

(donatore)

M. genitalium

crescita troppo lenta

crescita più veloce

M. capricolum subspecies capricolum

(ricevente)

Nel lievito il genoma sintetico non è metilato mentre il sistema di

restrizione presente nel ricevente richiede la metilazione

3 soluzioni proposte:

metilazione del DNA estratto da lievito (donatore) con metilasi

purificate

metilazione del DNA estratto da lievito (donatore) con estratti

crudi dalla specie di M. mycoides o M. capricolum

disattivazione del sistema di restrizione del ricevente

M. mycoides e M. capricolum possiedono il medesimo sistema di

restrizione!

Fasi del processo

Sequenziamento di due ceppi di M. mycoides subspecies capri:

CP001621 e CP001668 (le 2 sequenze differiscono per 95 siti ma sono

state considerate entrambe affidabili)

Disegno di “cassette” geniche sulla base della sequenza del ceppo

CP001668.

Aggiunta di 4 watermarks per differenziare ulteriormente il genoma

sintetico dal naturale.

Strategia di assemblaggio del genoma sintetico

Cassette geniche di 1080 pb con

80 pb che si sovrappongono alla

cassetta adiacente

Sintesi di oligonucleotidi affidata

alla Blue Heron

Inserzione di un sito di restrizione

Not I nelle cassette e negli

intermedi di assemblaggio

Assemblaggio gerarchico in 3

passaggi

I PASSAGGIO: ASSEMBLAGGIO DI INTERMEDI

SINTETICI DI 10 Kb

• For the first stage of assembly, a yeast/E. coli

shuttle vector, termed pCC1BAC-LCYEAST, was

produced

• Cassette e un vettore sono ricombinati in lievito

(sovrapposizione cassette da 1Kb per formare

quelle da 10 Kb)

• Trasferimento in E. coli

• Screening delle cellule e

selezione dei cloni

contenenti il DNA plasmidico

In general, at least one 10-kb assembled

fragment could be obtained by screening 10 yeast clones

• Sequenziamento e selezione dei cloni che non

contengono errori per il passaggio successivo

Nineteen out of 111 assemblies contained errors. Alternate clones were

selected, sequence-verified, and moved on to the next assembly stage

II PASSAGGIO: ASSEMBLAGGIO DI INTERMEDI

SINTETICI DI 100 Kb

•

Ricombinazione in lievito per dare intermedi

di 100 Kb

•

Estrazione del DNA ricombinante dal lievito

(no trasferimento in E.coli, perché non è stabile)

•

Multiplex PCR (coppia di primer per ogni 10 Kb) per

verificare la presenza di tutti gli ampliconi = assemblaggio

corretto. In general, 25% or more of the clones screened

contained all of the amplicons expected for a complete

assembly

•

Dimensione corretta verificata su gel di

agarosio: a second stage assembly intermediate of the

correct size was usually produced. In some cases, however,

small deletions occurred. In other instances,multiple 10-kb

fragments were assembled, which produced a larger

second-stage assembly intermediate

III PASSAGGIO: COMPLETO ASSEMBLAGGIO

DEL GENOMA

•

Isolamento degli 11 frammenti circolari

(100 Kb) da sferoplasti di lievito mediante

lisi alcalina

•

Le 11 cassette sono state assemblate in

lievito

•

Digestione di una piccola frazione degli

intermedi con Not I e purificazione

attraverso FIGE

•

PCR Multiplex a livello delle giunzioni per

verificare il corretto assemblaggio

•

Genoma di M. mycoides assemblato!!

In preparation for the final stage of assembly, it was necessary to isolate each of the 11 second-stage

assemblies from yeast spheroplasts by an alkaline-lysis procedure.

To further purify the 11 assembly intermediates, they were treated with exonuclease and passed

through an anion-exchange column. A small fraction of the total plasmid DNA (1/100) was digested

with Not I and analyzed by field-inversion gel electrophoresis (FIGE).

The method above does not completely remove all of the linear yeast chromosomal DNA, which we

found could substantially decrease the yeast transformation and assembly efficiency. To further enrich

for the 11 circular assembly intermediates, ~200 ng samples of each assembly were pooled and mixed

with molten agarose. As the agarose solidifies, the fibers thread through and topologically “trap”

circular DNA. Untrapped linear DNA can then be separated out of the agarose plug by electrophoresis,

thus enriching for the trapped circular molecules. The 11 circular assembly intermediates were digested

with Not I so that the inserts could be released. Subsequently, the fragments were extracted from the

agarose plug, analyzed by FIGE, and transformed into yeast spheroplasts . In this third and final stage of

assembly, an additional vector sequence was not required because the yeast cloning elements were

already present in assembly 811-900.

“Trapianto” del genoma sintetico nella cellula

ricevente

Il genoma sintetico di M. mycoides contenuto nel lievito

YCp235 viene “trapiantato” nella cellula ricevente M.

capricolum (con sistema di restrizione inattivo)

Selezione delle colonie contenenti il genoma

sintetico è fatta mediante crescita in terreno

selettivo SP4 con tetraciclina e X-gal a 37˚C

Sequenziamento

Sequenziamento del genoma di M. mycoides JCVI-syn1.0 e

confronto con il genoma minimo disegnato

Diversità:

8 SNP

Trasposone omologo a quello di E. coli (ISI)

Duplicazione di 85bp

The transposon insertion exactly matches the size and sequence of IS1, a transposon in E.

coli. It is likely that IS1 infected the 10-kb subassembly following its transfer to E. coli. The

IS1 insert is flanked by direct repeats of M. mycoides sequence, suggesting that it was

inserted by a transposition mechanism. The 85-bp duplication is a result of a

nonhomologous end joining event, which was not detected in our sequence analysis at the

10-kb stage. These two insertions disrupt two genes that are evidently nonessential.

Assenza di sequenze di M. capricolum: completo

rimpiazzo del genoma sintetico

Osservazione morfologica

Cellula sintetica in grado di replicarsi autonomamente con curva di

crescita logaritmica

Osservazione colonie (piastre con agar SP4 e X-gal) con microscopio

ottico

M. mycoides

JCVI-syn1.0

WT

Ulteriori analisi:

Analisi proteomica, mediante elettroforesi

bidimensionale

Confrontati i profili di M. mycoides con genoma

sintetico e del ceppo wild-type

Risultato: i profili sono identici

Saggi di colorazione e tasso di crescita (confrontata la

velocità di crescita tra sintetico e wild-type)

presentano lievi differenze

CONCLUSIONI

Ottenere un genoma sintetico senza errori è una pratica

molto complessa

Questo lavoro rappresenta la base per l’assemblaggio e la

caratterizzazione di un genoma sintetico

Si sono apportate piccole modifiche alla sequenza di partenza,

ma nulla impedisce a lavori futuri, di apportare maggiori

modifiche in base alle varie richieste biotecnologiche

Questo lavoro ha aperto una serie di discussioni di tipo etico

Com’è arrivata al mondo

questa informazione??

La Repubblica

GENETICA

Nasce la prima vita artificiale

"Ecco la cellula in laboratorio"

Su Science l'annuncio del gruppo guidato da Craig Venter: un batterio col Dna

sintetico. "Può riprodursi". Obiettivo: creare nuovi farmaci e salvare il clima

di ELENA DUSI

Corriere della Sera

Ecco l'inizio della «vita artificiale»

Costruita la prima cellula

Svolta epocale nella ricerca. È controllata da un Dna sintetico ed è in grado di

dividersi e moltiplicarsi

The Economist

Artificial lifeforms

Genesis redux

A new form of life has been created in a laboratory, and the era of synthetic

biology is dawning

May 20th 2010