|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

COLOFON

BELGISCH HISTORISCH INSTITUUT ROME |

INSTITUT HISTORIQUE BELGE DE ROME

Via Omero 8 - I–00197 ROMA

Tel. +39 06 203 98 631 - Fax +39 06 320 83 61

http://www.bhir-ihbr.be

Postadres | adresse postale | recapito postale |

mailing address

Vlamingenstraat 39 - B-3000 LEUVEN

Tel. +32 16 32 35 00

Redactiesecretaris | Sécretaire de rédaction |

Segretario di redazione | Editorial desk

Prof. dr. Françoise Van Haeperen

[[email protected]]

ISSN 2295-9432

Forum Romanum Belgicum is het digitale forum van het Belgisch Historisch Instituut te Rome, in opvolging van het Bulletin van het BHIR, waarvan de laatste aflevering nr. LXXVII

van jaargang 2007 was.

Forum Romanum Belgicum wil met de digitale formule sneller en frequenter inspelen op de resultaten van het lopend

onderzoek en zo een rol spelen als multidisciplinair onderzoeksforum. Door de digitale formule kan een artikel, paper

(work in progress) of mededeling (aankondiging, boekvoorstelling, colloquium enz.) onmiddellijk gepubliceerd worden. Alle afleveringen zijn ook blijvend te raadplegen op de

website, zodat Forum Romanum Belgicum ook een e-bibliotheek wordt.

Voorstellen van artikels, scripties (work in progress) en mededelingen die gerelateerd zijn aan de missie van het BHIR

kunnen voorgelegd worden aan de redactiesecretaris prof.

dr. Claire De Ruyt ([email protected]). De technische instructies voor artikels en scripties vindt u hier. De

toegelaten talen zijn: Nederlands, Frans, Engels en uiteraard

Italiaans.

Alle bijdragen (behalve de mededelingen) worden voorgelegd aan peer reviewers vooraleer gepubliceerd te worden.

Forum Romanum Belgicum est forum digital de l’Institut Historique Belge à Rome, en succession du Bulletin de l’IHBR,

dont le dernier fascicule a été le n° LXXVII de l’année 2007.

La formule digitale de Forum Romanum Belgicum lui permettra de diffuser plus rapidement les résultats des recherches en cours et de remplir ainsi son rôle de forum de

recherche interdisciplinaire. Grâce à la formule digitale, un

article, une dissertation (work in progress) ou une communication (annonce, présentation d’un livre, colloque etc.)

pourront être publiés sur-le-champ. Tous les fascicules pourront être consultés de manière permanente sur l’internet,

de telle sorte que Forum Romanum Belgicum devienne aussi

une bibliothèque digitale.

Des articles, des notices (work in progress) et des communications en relation avec la mission de l’IHBR peuvent

être soumis à la rédaction: prof.dr. Claire De Ruyt (claire.

[email protected]). Vous trouverez les instructions techniques pour les articles et les notices à Les langues autorisées sont le néerlandais, le français, l’anglais et bien entendu l’italien.

Toutes les contributions (sauf les communications) seront

soumises à des peer reviewers avant d’être publiées.

Child Cremation

Sanctuaries

(“Tophets”) and

Early Phoenician

Colonisation: Markers of Identity?

Valentina Melchiorri*

The topic

TOPHET: A (Biblical) Hebrew term conventionally used to denote Phoenician and Carthaginian cremation child sanctuaries that were widespread throughout the central Mediterranean

(Carthage, Sulci, Motya and later, Tharros, Nora,

Monte Sirai, etc.) from the 8th century BC. The

cremated remains, either of children (mainly infants) or of animals (mostly very young sheep

and goats), or even mixed together, are preserved in morphologically various ceramic urns.

Sometimes votive objects are found together

with these urns, e.g. unguentary vases, jewels

and stelae, either blank or inscribed.

Methodological issues and

general aspects of the evidence

Even today, the tophet is the subject of lively

debate in academic circles. Here, new interpretations and original research perspectives, still in

progress, have been proposed, after many years

of partial and occasionally biased approaches,

largely inadequate in view of the complexity

of such a topic.1 Important progress has been

*

1.

Marie Curie Fellow of the “Gerda Henkel Stiftung”

(Duesseldorf). I am very grateful to the Foundation for the provided support.

For the most recent contributions about general problems (and the various positions, often

different) see Bernardini, “Per una rilettura del

santuario tofet – I”. Bernardini, “Leggere il tofet”.

Ciasca, “Archeologia del tofet”. Xella, “Per un modello interpretativo del tofet”. Bonnet, “On Gods

and Earth”. D’Andrea-Giardino, “Il tofet: dove e

perché”. Quinn, “The Cultures of the Tophet”. Bartoloni, “Appunti sul tofet”. Xella, “Il tophet”. Xella,

“Le tophet comme problème historique”. Xella,

Quinn, Melchiorri and Van Dommelen, “Phoenician

Bones of Contention”.

|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

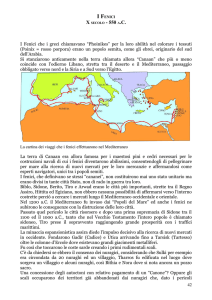

1. Map of the Mediterranean Sea with location of the main Phoenician diaspora settlements: in evidence the three

earliest tophet sites.

Adapted from Bondì et al., Fenici e Cartaginesi, fig. 3, 95.

made in the last few years regarding both method and the extension of the topic. This is due

to the focus on some ritual aspects and, more

generally, to careful attempts to contextualise

diachronically the tophet within the framework

of the western Mediterranean of the 1st millennium BC.2 For a long time, the tophet was considered as peculiar to the Phoenician colonial world

– particularly, in the central Mediterranean – due

to a lack of archaeological evidence in the Levant

and in the Far West, and also because the tophet has been characteristic of several Phoenician

“colonies” in Northern Africa, Sicily and Sardinia

since their foundation (8th century BC).3 Nevertheless, the approaches to the subject have often

been overgeneralised, and have not always taken into due consideration the range of evidence

according to its different historical phases. What

we conventionally call to be maintained tophet

is a historically complex phenomenon that has

changed significantly over the centuries. Indeed,

the contexts dating back to approximately the 6th

2.

3.

See, in particular, Xella, “Per un «modello interpretativo» del tofet”. Quinn, “The Cultures of the

Tophet”.

Aubet, Tiro y las colonias fenicias de Occidente,

214, 216 («El tofet consituye sin duda la manifestación cultural más caraterísticas de los asentamientos fenicios del Mediterráneo central» […]

«El tofet nos interesa particularmente, porque

constituye en Occidente la entidad socio-religiosa más representativa de los establecimientos

and 5th centuries BC, and, above all, later sanctuaries, dated between the 2nd century BC and the

2nd-3rd centuries AD, are quite different from the

earliest ones. As a consequence, it is important

to match the analytical approach to the specific

documentation of each historical phase.

As is well known, the earliest contexts available are Carthage (Tunisia) and Sulci (Sardinia),

both dated within the first half of the 8th century. Immediately afterwards, there is Motya

(Sicily), dated from the end of the same century

(fig. 1).4 These are precisely the contexts and

the historical phases that the present inquiry intends to investigate, in an attempt to understand

whether the tophet can be considered as a specific cultural and ethnic (particularly Phoenician)

marker in this period. The first objective of the

inquiry is to focus on the shared characteristics

and peculiarities of these ancient sites where the

earliest tophets were found. Secondly, comes

the attempt to reconstruct their possible social

4.

fenicios de Túnez, Sicilia y Cerdeña »). Moscati,

“Non è un tofet a Tiro”, 149 (« […] Il tofet è una

componente caratteristica, basilare e diffusa nel

mondo punico occidentale […] »).

On Carthage, Bénichou-Safar, Le tophet de Salammbô à Carthage. On Sulci, Bernardini, “Recenti indagini nel santuario tofet di Sulci”; Melchiorri,

“Le tophet de Sulci (S. Antioco, Sardaigne)”.

About Motya, Ciasca, “Mozia”.

|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

Obviously, even if the central Mediterranean dimension is the core of the analysis, it is wise to consider the general situation of the documentation for

the 8th century BC. This includes both the Levant

(i.e. the Phoenician motherland) and the Far West

(the Iberian Peninsula and the Atlantic regions, also

“theatres” of the so-called Phoenician colonisation),

according to their different “geo-political” premises

and specific historical developments.6

As for the terms “colonisation”, “culture” and

“ethnicity”, further refinement is necessary, concerning both the meaning and the use of such

concepts in connection with our theme – the

“tophet”. Several elements contribute to making

this still fluid field of research, which requires

further thorough analysis and new approaches.

The open questions include not only the basic

terminology but also further aspects, such as

ritual -, social -, cultural - and, more generally,

historical interpretation.7

2. Carthage: settlement planimetry.

From Gras, Rouillard, Teixidor, L’universo fenicio, fig. 24,

259.

features at the beginning of their existence and

the historical significance of those sanctuaries

as archaeological (and cultural?) markers, in

the general framework of the so-called western

Phoenician colonisation.5

5.

6.

7.

The concept of the “West” is very indefinite, as

emphasised inter alia by Braudel, “Les Mémoires

de la Méditerranée”, 193-196.

For the “Tyrrhenian dimension”, and the development of individual historical dynamics, see Gras,

Trafics tyrrhéniens archaïques, 8, followed by

Moscati, “Dimensione tirrenica”. The tophet can

be understood only within the framework of the

setting where Phoenicians moved from East to

West. For a general historical account, see Aubet,

Tiro y las colonias fenicias de Occidente. Niemeyer, “The Phoenicians in the Mediterranean”.

Krings, ed., La civilisation phénicienne et punique.

López Castro, ed, Las ciudades fenicio-púnicas en

el Mediterráneo Occidental. Sagona, ed., Beyond

the Homeland. Helas and Marzoli, eds., Phönizisches und punisches Städtewesen.

In the frame of the discussion concerning the

evaluation of the tophet as a child-necropolis, and

its interpretation as a sanctuary – which is largely

As far as the terminology is concerned, the very

typological definition of the sanctuary is open to

several options, due to the possible multi-functionality of the tophet. While it is a sacred/consecrated place, which eludes rigid classification,

it does not exhibit – at least in the first phases

of its existence – very uniform characteristics,

or allow easy definitions. In my opinion, the labels “urban” (“peri-urban”, “sub-urban”, or even

“extra-urban”) for this sanctuary should be excluded because the term “urban” itself seems inadequate: for this earliest chronological phase

– perhaps with the exception of Carthage – it

is impossible to acknowledge these settlements

as fully “urban” centres (fig. 2).8 However, the

problem remains of finding a definition that can

8.

the prevalent view now – the problem of possible child-sacrifices must also be added. A very

lively debate is still in progress, and considerable

arguments in support of the sacrificial character

of the rites have recently been proposed, see

e.g. the overall summary in Xella, “Il tophet”. A

collective volume on this topic – a special issue of

the journal “Studi epigrafici e linguistici sul Vicino

Oriente antico” – has recently been published,

in 2013. For definitions of the so-called “sacred

space”, see in general Dupré Raventós, Ribichini

and Verger, eds., Saturnia Tellus.

The organisation and functional structure of the

earliest Phoenician sites is still the object of scholarly debate. The hypothesis that urbanisation was

not yet a fait accompli, during the 8th century BC,

seems the most convincing. For a general picture,

see Helas and Marzoli, eds., Phönizisches und punisches Städtewesen. On Carthage as a real “town”

since its foundation see Lancel, Carthage, 49 ff.

|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

the same period or earlier – of similar contexts,

even if the general idea of an open space lacking

independent and/or monumental buildings may

have an Oriental origin. Perhaps, it is hypothetical to mention the enigmatic Hebrew bamôt,

commonly translated “high places”, of Syro-Palestinian (biblical) tradition.9 Nevertheless, some

Old Testament passages clearly speak of bamôt

in connection with child sacrifice (passed into

the fire), and the place called tophet (see e.g.

Jer. 7,31-32; 19,4-6; 32,35; Ez. 20,28-29), so

the parallel is not too audacious. However, other evidence (even if not purely archaeological,

but mainly inscriptions and literary documents)

strongly suggests a Levantine origin for this particular type of sanctuary and its related rites.10

3. Sulci: tophet view with in situ replacement of modern

copies of the urnes. Photo: V. Melchiorri (with kind permission of the “Soprintendenza per i Beni Archeologici

per le Province di Cagliari e Oristano”).

The analysis of the Phoenician documentation

from these centuries prompts some additional

remarks.11 Even excluding the tophet, no specific typologies of sacred/consecrated spaces are

known for the 9th-8th centuries in Phoenicia. As

a consequence, we are in no position to speak

of absences or presences in the West, and, even

less of a distancing, be it more or less conscious,

from the motherland traditions.

As mentioned above, the Levantine motherland

provides no archaeological evidence – either for

In other words, we cannot state that the institution of the tophet represents a break with the

traditional world of the Phoenician motherland,

simply because sacred architectural typologies

have not been found (or are not clearly recognisable) for these centuries. Therefore, the main

datum emerging in the Levantine motherland is

a nearly total lack of homogeneity in our evidence.12 Even if this does not fully invalidate the

interpretation of the tophet as a completely new

(archaeologically speaking) element, characteristic of the diaspora world, it surely puts its significance as a totally innovative and revolutionary (as regards the motherland) “cultural fact”

into perspective. Evidently, the dichotomy tradition versus innovation cannot be used here;

this is due to the aforementioned absence of archaeological evidence in the motherland, that in

this period is a heterogeneous context, without

the possibility of identifying precise typological

9.

12.

express the highly representative and symbolic

value to be ascribed to this sanctuary: it is very

probable that it can be considered a primary institution, which characterises the initial facies of

these centres’ lifespan. It is tempting to propose

that the basic binomial “built-up area/tophet”

can be interpreted as a kind of identity card of

the first Phoenician settlements in the central

Mediterranean. At any rate, the most peculiar

morphological feature of the tophet is an open

area that is defined by itself, by its very nature,

without specific spatial limits or actual buildings

above ground: the only visible and constant

markers are the urns themselves, emerging

from the walking-level of the sanctuary (fig. 3).

10.

11.

The relevant bibliography is very extensive. See

recently Barrick, “BMH as Body Language”.

Xella, “Le tophet comme problème historique”.

For a historical description of Phoenicia between

the 9th and 8th centuries BC, see Aubet, Tiro y

las colonias fenicias de Occidente, 38-42, 44-49.

Bernardini, “La Sardegna e i Fenici”. Bunnens,

“L’histoire événementielle partim Orient”.

It is also necessary to keep in mind the scarcity

of urban and architectural evidence in the motherland. For a comprehensive view, see Cecchini,

“Architecture militaire, civile et domestique partim

Orient”. Perra, L’architettura templare fenicia e

punica di Sardegna, passim.

|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

4. Carthage: tophet original contexts inside general stratigraphy.

From Bénichou-Safar, Le tophet de Salammbô à Carthage, Pl. XXV.

models to be assumed as terms of comparison

for the West.13

The contextual analysis: the best

way to a scientific approach

been analysed, mostly separately, especially stelae and urns. As a matter of fact, there is an

ever more pressing need to consider the whole

documentation through a deeper and exhaustive

approach, without omitting information of any

kind.

If we now look at the evidence from the western Mediterranean, a large amount of data and

of complex archaeological contexts is available,

but so far the analytical approaches have been

excessively general: the tophet has been seen as

a common Western phenomenon, without identifying internal variations according to the different historical periods, and the specific nature of

each corpus of evidence in its regional context.14

Moreover, only certain classes of material have

The increase of evidence should allow the compilation of more precise and complete archaeological corpora than those actually at our disposal:

first, through a careful classification of previous

data; second, through the systematic insertion

of new information, also in order to fill surprising

– and often quite inexplicable – gaps in the documentation.15 Each corpus (material culture, osteological data, epigraphy, literary sources) must

be analysed in se, but the resulting data have

13.

14.

15.

Regarding the documentation on the tophet in the

Levant, it is important to remember that, even

if we lack contextual architectural and archaeological evidence, on the contrary, there are some

epigraphic and literary data, e.g. the inscription

from Nebi Yunis, some biblical sources and passages by classical authors. The relevant material

has been collected in Xella,“ Le tophet comme

problème historique”.

Neverthless exhaustive works exist for Carthage

and Motya, see Bénichou-Safar, Le tophet de

Salammbô à Carthage. Ciasca, “Mozia”.

As an example, we can mention osteological

analysis, overlooked for too long in compari-

son with the large number of studies on stelae

and pottery. For a reassessment, see Melchiorri,

“Osteological Analysis in the Study of the Phoenician and Punic Tophet”. For recent discussion,

see Schwartz, Houghton, Macchiarelli and Bondioli, “Skeletal Remains from Punic Carthage Do

Not Support Systematic Sacrifice of Infants”;

Smith, Avishai, Green and Stager, “Aging cremated infants”; Schwartz, Houghton, Bondioli and

Macchiarelli, “Bones, teeth, and estimating age of

perinates”; Xella, Quinn, Melchiorri and Van Dommelen, “Phoenician bones of contention”.

|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

to be incorporated into the whole. The concrete

evidence should be the focus of attention: first of

all, I suggest, the depositional contexts, and not

the individual classes of materials separated according to their respective contexts. The various

classes of materials must not be considered as

independent significant categories, but must be

interpreted primarily on the basis of the relational connections they have within each context.

Therefore, an upset of analytical perspective is

required, together with a return to the contextual unity and the material documentation, which

only permits the identification of its structural

aspects (fig. 4).

To return to the evidence from the most archaic tophets: the dossier at our disposal is quite

meagre, in comparison with the data from later periods, and is almost entirely restricted to

the cinerary urns. This is exactly why I believe

that the only possible key analysis is a careful

study of the “depositional contexts” – i.e. each

urn in its own context, considered as the basic

unity to lay out the analysis – examined in all its

constitutive parts: container + contents + other

(possible) associated elements. It is a difficult

task due to the general character of the documentation, particularly because we do not have

absolutely assured chrono-typological grids for

the pottery. As a consequence, it is not always

easy to precisely date the most ancient levels

of the contexts. Therefore, we also lack precise

evaluations about the percentages of materials

to ascribe to each historical phase, an essential

element in order to understand diachronically the historical and cultural significance of the

events. However, the only road to follow is to

expand our dossiers carefully, and adhere closely to the material data. The tophet must not be

a field for speculation and theoretical flights of

fancy, rather one should keep in mind that material culture is one of the most important steps

in our interpretation.

“Ethnicity” and “identity”?

The study of the tophet as a

social, cultural and historical fact

Concerning the analytical perspective, it is a truism to note that it is necessary to make use of

several conceptual tools as elaborated by the social sciences, especially the critical development

of complex concepts such as “culture”, “ethnicity” or “identity”. As is well known, these are basic social and anthropological macro-categories,

sometimes used in a too general and somewhat

uncritical way, particularly within Phoenician

studies. In fact, their definition and limits are still

hotly debated by ethno-anthropologists as well.

As far as archaeology - a cumulative historical

science that aims at reconstructing the past

through “mute” sources (and not through living informants) - is concerned, the applicability

of these concepts must be prudently evaluated

and verified. One runs the risk of using vague (if

not empty!) stereotypes, with little (if any) relevance to vanished societies, whose conceptual

categories are almost totally unknown to us: e.g.

our concept of “identity” seems too arbitrary to

be applied at a theoretical level to Phoenician

society, which in turn is highly undefined.

Even though methodological caution is strongly required, and in spite of many difficulties,

the tophet may be considered an unusual case

study, a valuable “observatory” for understanding the various social dynamics within complex

settlements.16

Following this track, we may wonder what kind

of culture, ethnic group and cultural identification processes can be conjectured for the historical contexts of the 8th century BC, when some

of the earliest centres – traditionally related to

Phoenician “colonisation” – began life and started to develop. Regarding these aspects, can the

tophet be considered a specific cultural symbol, the manifestation of a precise social will of

self-representation?

In our discipline, the term “culture” is most commonly accepted as a synonym for “civilisation”,

like Kultur, with a collective meaning, i.e. the totality of the particular aspects that distinguish

one people from another. But in these terms,

“culture” almost overlaps with the concept of

16.

Quinn, “The Cultures of the Tophet”, 389-391.

|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

“ethnicity”, i.e. the identification of distinguishing and recognisable elements that characterise

an ethnic group.17 It is not surprising, therefore,

that for a long time “culture” was a conceptual

category “in crisis” even in anthropological studies, subject to continual criticism because – even

as a heuristic tool – it is difficult to be defined

once and for all.18 Far from being the static and

clearly defined sets that we sometimes imagine,

the different “cultures” are rather open and dynamic systems, subject to unceasing contamination and exchange, of different importance and

degree. It is precisely this meaning of “culture”

that seems the best to be applied to earlier tophets, not as corresponding to a specific “ethnicity”, but as open contexts, where the meeting of

different ethnic groups continually produces new

meanings and symbolic values, useful to a social

strategy with different roots and goals.

As far as the concept of “colonisation” is concerned, additional specifications and restrictions

are required. Its applicability to the so-called

western Phoenician contexts has already been

criticised and revised, chiefly due to the modern implications that contaminate this term.

Furthermore, its basic ambiguity is due to the

traditional “Greek” meaning, which still remains

popular.19 I am convinced that this terminology

should be rejected, chiefly for the historical period under consideration here. In fact, the concept of “colony” calls for establishing categories

and internal functional hierarchies of spaces that

cannot be documented for these earliest Phoenician settlements in the central Mediterranean. As

a consequence, it seems better to speak of a “diaspora world”, rather than of a “colonial world”20,

even if the choice of these terms is not free from

17.

18.

19.

For a survey of the interpretations, beginning with

E. B. Tylor and F. Boas, see inter alia Fabietti, Alle

origini dell’antropologia, 32-50. Fabietti, L’identità etnica. More extensively, Izard, Galaty and

Leavitt, “Cultura”. Lastly, a good overall summary

is Remotti, Cultura, with general bibliography.

Specific focus on these topics also in Jones, The

Archaeology of Ethnicity. Shennan, ed, Archaeological Approaches to Cultural Identity.

For exactly this reason, “culture” has been

considered by anthropologists to be a real “deception” of our modern mentality”. See Geertz,

Interpretations of cultures; Clifford, I frutti puri

impazziscono; and many others.

See e.g. Niemeyer, “The Phoenicians in the Mediterranean”. Braudel, Les Mémoires de la Méditerranée, 207. As for recent contributions, see e.g.

Bernardini, “Neapolis e la regione fenicia del Golfo

di Oristano”, 96-97. Dietler, “The archaeology of

basic criticism. As a matter of fact, this definition takes into account the perspective of the

“incomers”, i.e. the subjects actively involved in

migratory movements from the East towards the

West, rather than that of the local people already

living in these regions.

However, during the 8th century BC, the most

important centres of the central Mediterranean

region seem to be far from having a full urban

organisation of the territory. It is probably an in

fieri process, and the dimensions of the early

conglomerations seem indicative of an “experimental” phase, when urban planning was not

yet complete. I agree with the remarks made

by P. Bernardini in several of his works: chiefly

for these early periods, it is convenient to find

an alternative model of interpretation, a model

that foresees a progressive development of the

settlements that achieved a more accomplished

organisation only later, perhaps during the 7th

century BC.21 Nevertheless, it is true that the

built-up area and the tophet are precisely the

two (“proto-urban”?) structures around which

the settlements progressively grow up. There

is strong evidence for this in all the three sites

of Carthage, Sulci and Motya, where the tophet

was introduced almost at the same time as most

archaic built-up nuclei.

For these early communities, forms of peaceful

cohabitation between local and Phoenician ethnic groups have often been suggested, particularly on the basis of the presence of hand-made

pottery – usually ascribed to local productions

– in the most ancient strata of the tophet-sanctuaries. Nevertheless, the most surprising fact is

that such associations are not so frequent in the

20.

21.

colonization and the colonization of archaeology”.

Hurst and Owen, eds., Ancient Colonisations. Van

Dommelen, “Colonial matters”. Knapp and Van

Dommelen, “Material Connections”, 3-5.

Quinn, “The Cultures of the Tophet”.

Bernardini, “Neapolis e la regione fenicia del Golfo

di Oristano”. Bernardini, “Sulki fenicia”. The situation of Greek colonial settlements seems to be

quite different: in some cases, Greek foundations,

which have a certain numerical consistency, are

real poleis in status nascendi, well established in

the territory, comprising owners of plots of land,

and on the road to achieving identity and civicpolitical dimensions, see Giangiulio, “Avventurieri, mercanti, coloni, mercenari”, 505. On general

aspects see Malkin’s recent works: “Exploring the

Validity of the Concept of «Foundation»; “Foundations”; see Malkin, “Greek colonisation”.

|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

corresponding built-up areas.22 From this point

of view, the tophet would seem to be the place

appointed in order to create – at least at a symbolic level – a progressive (and still in fieri, for

this chronological phase) social integration between different ethnic groups. In coherence with

this analysis, the tophet may be seen as a new

“cultural phenomenon” but I do not mean here

an “ethnic” manifestation, but a social fact, a

way to create a composite community and to facilitate the cohesion of its components. In other

words, it is perhaps the occasion to achieve not a

univocal, but a complex social identity, a collective identity that goes beyond ethnic roots. The

aim seems to be a quest for new ways of aggregation, to warrant the maintenance of a social

order and, in the last resort, to affirm “urban

identity” which was to be the definitive achievement only of a later historical facies.

22.

In particular this seems evident at Sulci, see Bernardini, “I Fenici nel Sulci”. Bernardini, “Recenti

indagini nel santuario tofet di Sulci”. Regarding

Motya, see Ciasca, “Mozia”, passim.

Bibliography

Aubet, María Eugenia. Tiro y las colonias fenicias

de Occidente. Barcelona: Ediciones Bellaterra, 1987.

Barrick, Boyd William. BMH as Body Language: A

Lexical and Iconographical Study of the Word BMH

When not a Reference to Cultic Phenomena in Biblical and Post-Biblical Hebrew. London-New York: T&T

Clark, 2008.

Bartoloni, Piero. “Appunti sul tofet” in: Valentino

Nizzo and Luigi La Rocca, eds. Antropologia e archeologia a confronto: Rappresentazioni e pratiche del

sacro. Atti del 2° Incontro Internazionale di Studi,

Museo Nazionale Preistorico Etnografico “Luigi Pigorini” (Roma, 20-21 maggio 2011). Roma: ESS Editorial

Service System, 2012, 215-221.

Bénichou-Safar, Hélène. Le tophet de Salammbô à

Carthage. Essai de reconstitution. Collection de l’École

Française de Rome 342. Roma: École Française de

Rome, 2004.

Bernardini, Paolo. “Sulky fenicia. Aspetti di una comunità di frontiera” in: Sophie Helas and Dirce Marzoli, eds. Phönizisches und punisches Städtewesen.

Akten der internationalen Tagung in Rom vom 21. bis

23. Februar 2007. Iberia Archaeologica 13. Mainz am

Rhein: Philipp Von Zabern, 2009, 389-398.

Bernardini, Paolo. “La Sardegna e i Fenici. Appunti

sulla colonizzazione”. Rivista di Studi Fenici, 21 (1993)

1, 29-81.

Bernardini, Paolo. “I Fenici nel Sulci: la necropoli di

San Giorgio di Portoscuso e l’insediamento del Cronicario di Sant’Antioco” in: Piero Bartoloni and Lorenza Campanella, eds. La ceramica fenicia di Sardegna.

Dati, problematiche, confronti. Atti del Primo Congresso Internazionale Sulcitano (S. Antioco, 19-21

settembre 1997). Collezione di Studi Fenici 40. Roma:

Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, 2000, 29-61.

Bernardini, Paolo. “Leggere il tofet: sacrifici e sepolture. Una riflessione sulle fasi iniziali del tofet”. Epigrafia e antichità, 18 (2002), 15-27.

Bernardini, Paolo. “Neapolis e la regione fenicia del

golfo di Oristano” in: Raimondo Zucca, ed. Splendidissima civitas Neapolitanorum. Collana del Dipartimento

di Storia dell’Università di Sassari 27. Roma: Carocci,

2005, 67-123.

Bernardini, Paolo. “Per una rilettura del santuario

tofet – I: il caso di Mozia. Sardinia, Corsica et Baleares

Antiquae, III (2005), 55-70.

Bernardini, Paolo. “Recenti indagini nel santuario

tofet di Sulci” in: Antonella Spanò Giammellaro, ed.

Atti del V Congresso Internazionale di Studi Fenici e

Punici (Marsala-Palermo, 2-8 ottobre 2000). Vol. III.

Palermo: Università degli Studi di Palermo, 2005,

1059-1069.

Bondì, Sandro Filippo; Botto, Massimo; Garbati,

Giuseppe and Oggiano, Ida. Fenici e Cartaginesi. Una

civiltà mediterranea. Roma: Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 2009.

Bonnet, Corinne. “On Gods and Earth: The Tophet and the Construction of a New Identity in Punic

Carthage” in: Erich Stephen Gruen, ed. Cultural Identity in the Ancient Mediterranean. Los Angeles (CA):

Getty Research Institute, 2011, 373-387.

Braudel, Fernand. Les Mémoires de la Méditerranée. Paris: Éditions de Fallois, 1998.

|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

Bunnens, Guy. “L’histoire événementielle partim Orient” in: Véronique Krings, ed. La civilisation

phénicienne et punique. Manuel de recherche. Leiden-New York-Köln: Brill, 1995, 223-236.

Cecchini, Serena. “Architecture militaire, civile et

domestique partim Orient” in: Véronique Krings, ed.

La civilisation phénicienne et punique. Manuel de recherche. Leiden-New York-Köln: Brill, 1995, 389-396.

Ciasca, Antonia. “Mozia: sguardo d’insieme sul

tofet”. Vicino Oriente, 8 (1992), 113-155.

Ciasca, Antonia. “Archeologia del tofet” in: Carlos

González Wagner and Luis Alberto Ruiz Cabrero, eds.

El Molk como concepto del sacrificio púnico y hebreo

y el final del Dios Moloch. Madrid: Centro de Estudios

Fenicios y Púnicos, 2002, 121-140.

Clifford, James. I frutti puri impazziscono. Etnografia, letterature e arte nel secolo XX. Torino: Bollati

Boringhieri, 1993.

D’Andrea, Bruno and Giardino, Sara. “«Il tofet:

dove e perché»: alle origini dell’identità fenicia”. Vicino & Medio Oriente, XV (2011), 133-157.

Dietler, Michael. “The archaeology of colonization

and the colonization of archaeology: theoretical reflections on an ancient Mediterranean colonial encounter”

in: Gil Stein, ed. The Archaeology of Colonial Encounters: Comparatives Perspectives. Santa Fe: School of

American Research Press, 2005, 33-68.

Dupré Raventós, Xavier; Ribichini, Sergio and Verger, Stéphane, eds. Saturnia Tellus. Definizioni dello

spazio consacrato in ambiente etrusco, italico, fenicio-punico, iberico e celtico. Atti del Convegno internazionale svoltosi a Roma dal 10 al 12 novembre 2004.

Roma: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, 2008.

Fabietti, Ugo. Alle origini dell’antropologia. Torino:

Boringhieri, 1980.

Fabietti, Ugo. L’identità etnica. Storia e critica di

un concetto equivoco. Roma: Carocci editore, 200810.

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretations of Cultures.

New York: Basic Books Publishers, 2000.

Giangiulio, Maurizio. “Avventurieri, mercanti, coloni, mercenari” in: Salvatore Settis, ed. I Greci. Storia

Cultura Arte Società. Vol. 2.1. Torino: Einaudi, 1996,

497-525.

Gras, Michel. Trafics tyrrhéniens archaïques.

Roma: Bibliothèque des Écoles Françaises d’Athènes

et de Rome, 1985.

Gras, Michel; Rouillard, Pierre; Teixidor, Javier.

L’universo fenicio. Torino: Einaudi, 2008.

Hall, Stuart. “Cultural Identity and Diaspora” in:

Jonathan Rutheford, ed. Identity: Community, Culture, Difference. London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1990,

222-237.

Helas, Sophie and Marzoli, Dirce, eds. Phönizisches

und punisches Städtewesen. Akten der internationalen Tagung in Rom vom 21. bis 23. Februar 2007.

Iberia Archaeologica 13. Mainz am Rhein: Philipp Von

Zabern, 2009.

Hurst, Henry and Owen, Sarah, eds. Ancient Colonizations: Analogy, Similarity and Difference. London:

Duckworth, 2005.

Izard, Michel; Galaty, John and Leavitt, John. “Cultura” in: Pierre Bonte and Michel Izard, eds. Dizionario

di antropologia e etnologia. Marco Aime, ed. (italian

edition). Torino: Einaudi, 2009, 279-285.

Jones, Siân. The Archaeology of Ethnicity. Constructing identities in the past and present. London:

Routledge, 1997.

Knapp, Bernard Arthur and Van Dommelen, Peter.

“Material connections. Mobility, materiality and Mediterranean identities” in: Bernard Arthur Knapp and

Peter Van Dommelen, eds. Material connections in

the Ancient Mediterranean. Mobility, materiality and

Mediterranean identities. Oxon-New York: Routledge,

2010, 1-18.

Krings, Véronique, ed. La civilisation phénicienne

et punique. Manuel de recherche. Leiden-New YorkKöln: Brill, 1995.

Lancel, Serge. Carthage. Paris: Fayard, 1992.

López Castro, José Luis, ed. Las ciudades fenicio-púnicas en el Mediterráneo Occidental. Almería:

Centro de Estudios Fenicios y Púnicos-Universidad de

Almería, 2007.

Malkin, Irad. “Exploring the Validity of the Concept

of «Foundation»: A Visit to Megara Hyblaia” in: Vanessa B. Gorman and Eric W. Robinson, eds. Oikistes:

Studies in Constitutions, Colonies, and Military Power

in the Ancient World. Offered in Honor of A.J. Graham.

Leiden-Boston-Köln, 2002, 195-225.

Malkin, Irad. “Foundations” in: Kurt Raaflaub and

Hans van Wees, eds. A Companion to Archaic Greece.

Oxford: Wile-Blackwell, 2009, 373-394.

Malkin, Irad. “Greek colonisation: the right to return” in: Lieve Donnellan, Valentino Nizzo and GertJan Burgers, eds. Conceptualising early Colonisation.

Turnhout, 2016, 27-50.Melchiorri, Valentina. “Le

tophet de Sulci (S. Antioco, Sardaigne). État des études

et perspectives de la recherche”. Ugarit-Forschungen,

41 (2009) [2011], 509-524.

Melchiorri, Valentina. “Osteological Analysis in the

Study of the Phoenician and Punic Tophet: a History of Research”. Studi epigrafici e linguistici sul Vicino

Oriente antico, 29-30 (2012-2013). Verona: Essedue

Edizioni, 2013, 223-258.

Moscati, Sabatino. “Dimensione tirrenica”. Rivista

di Studi Fenici, 16 (1988) 2, 133-144.

Moscati, Sabatino. “Non è un tofet a Tiro”. Rivista

di Studi Fenici, 21 (1993) 2, 147-152.

Niemeyer, Hans Georg. “The Phoenicians in the

Mediterranean: a Non-Greek Model for Expansion and

Settlement in Antiquity” in: Jean-Paul Descoeudres,

ed. Greek Colonists and Native Populations. Proceedings of the First Australian Congress of Classical Archaeology Held in Honour of Emeritus Professor A. D.

Trendall (Sidney, 9-14 July 1985). New York: Oxford

University Press, 1990, 469-489.

Perra, Carla. L’architettura templare fenicia e punica di Sardegna: il problema delle origini orientali.

Oristano: S’Alvure, 1998.

Quinn, Josephine C. “The Cultures of the Tophet.

Identification and Identity in the Phoenician Diaspora”

in: Erich Stephen Gruen, ed. Cultural Identity in the

Ancient Mediterranean. Los Angeles (CA): Getty Research Institute, 2011, 388-413.

Remotti, Francesco. Cultura. Dalla complessità

all’impoverimento. Roma-Bari: Laterza, 2011.

Sagona, Claudia, ed. Beyond the Homeland: Markers in Phoenician Chronology. Ancient Near Eastern

Studies Supplement 28. Leuven: Peeters, 2008.

|FORUM ROMANUM BELGICUM | 2016|

Artikel |Article |Articolo 13.10

Valentina Melchiorri / Child Cremation Sanctuaries (“Tophets”) and Early Phoenician Colonisation

Schwartz, Jeffrey Hugh; Houghton, Frank; Bondioli, Luca and Macchiarelli, Roberto. “Bones, teeth, and

estimating age of perinates: Carthaginian infant sacrifice revisited”. Antiquity, 86 (2012), 738-745.

Schwartz, Jeffrey Hugh; Houghton, Frank; Macchiarelli, Roberto and Bondioli, Luca. Skeletal Remains

from Punic Carthage Do Not Support Systematic Sacrifice of Infants. PLoS ONE 5(2): e9177. doi.10.1371/

journal.pone.0009177 (2010).

Shennan, Stephen, ed. Archaeological Approaches

to Cultural Identity. London: Routledge, 20032.

Smith, Patricia; Avishai, Gal; Greene, John A. and

Stager, Lawrence Elliot. Aging cremated infants: the

problem of sacrifice at the Tophet of Carthage. Antiquity, 85 (2011), 859-874.

Van Dommelen, Peter. “Colonial matters. Material

culture and postcolonial theory in colonial situations”,

in: Cristopher Tilley; Webb Keane; Susan KuechlerFogden; Mike Rowlands and Patricia Spyer, eds. Handbook of Material Culture. London: Sage, 2006, 104124.

Xella, Paolo, “Le tophet comme problème historique. Under Eastern Eyes” in: Ahmed Ferjaoui, ed.

Actes du 6ème Congrès International d’Études Phéniciennes et Puniques (Hammamet, 10-14 novembre

2009). In press.

Xella, Paolo. “Per un «modello interpretativo» del

tofet: il tofet come necropoli infantile?” in: Gilda Bartoloni; Paolo Matthiae; Lorenzo Nigro and Licia Romano, eds. Tiro, Cartagine, Lixus: nuove acquisizioni. Atti del Convegno Internazionale in onore di Maria

Giulia Amadasi Guzzo (Roma, 24-25 novembre 2008).

Quaderni del Vicino Oriente 4. Roma: Università degli

Studi di Roma “La Sapienza”, 2010, 259-278.

Xella, Paolo. “Il tophet. Un’interpretazione generale” in: Simonetta Angiolillo; Marco Giuman and

Chiara Pilo, eds. MEIXIS. Dinamiche di stratificazione

culturale nella periferia greca e romana. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi “Il sacro e il profano”

(Cagliari, 5-7-maggio 2011). Roma: Giorgio Bretschneider Editore, 2012, 1-17.

Xella, Paolo; Quinn, Josephine; Melchiorri, Valentina and Van Dommelen, Peter. “Phoenician bones of

contention”. Antiquity, 87 (2013), 1199-1207.