AIDS: a chronic systematic

damage

AIDS: un danno cronico di sistema

A brief travel inside the world of the viruses,

ruthless predators, investigating on AIDS – the

21st century’s black death.

Un breve viaggio attraverso il mondo dei

virus, predatori spietati, approfondendo la

tematica dell’AIDS – la peste del XXI secolo

1

VIRUSES

VIRUS

What are viruses?

Cosa sono i virus?

Viruses are intracellular obliged parasites,

i.e. they need to infect a living cell to

replicate. Viruses do not have any structure

to replicate, they are very little and simple

and this is why they are regarded as nonliving creatures. The cell they infect dies

due to lack of energy and resources (ATP

and proteins), stress collapse or is destroyed

by the virus itself.

I virus sono parassiti intracellulari obbligati, cioè hanno bisogno di

una cellula vivente per duplicarsi. I virus non hanno alcuna struttura

riproduttiva, sono molto piccoli e semplici, per questo sono

considerati esseri non viventi. La cellula che infettano per replicarsi

muore per l’esaurimento di energia e risorse (ATP e proteine), per

collasso da stress o viene distrutta dal virus stesso.

The first virus to be identified, in 1898, was the one which causes a

disease called “mosaic” in tobacco plants, or

TMV (Tobacco Mosaic Virus). The Dutch

biologist Beijerink noticed that the pathogen he

isolated was too small to be a bacterium but too

big to be a toxin, so he called it “virus”. The

word “virus” comes from Latin and means

“poison”.

Il primo virus ad essere

identificato, nel 1898, è stato il

virus che causa la malattia del

mosaico nelle piante di tabacco,

o TMV (Tobacco Mosaic

Virus). Il biologo olandese

Beijerink notò che l’agente

patogeno che aveva isolato era

troppo piccolo per essere un batterio ma troppo grande per essere una

tossina, così lo chiamò “virus”. La parola “virus” viene dal latino e

significa “veleno”.

Over 5,000 viral species are known so far, but

scientists believe that there are a thousand times more: they live in

every habitat in the biosphere, everywhere there are organisms to

infect.

Fino ad oggi sono conosciuti più di 5000 specie virali, ma gli studiosi

ritengono che ce ne sia un numero mille volte più grande: essi vivono

in ogni habitat della biosfera, ovunque ci siano organismi da

parassitare.

.

2

The structure of a virus

La struttura di un virus

Virus alternate two different phases: at first they look like dead “genes

containers”; but as they enter the cell, they interosculate with it, losing

their individuality and starting a berserk biologic activity. When a

virus is outside the cell, it is called “virion”.

I virus alternano due fasi: in un primo momento essi si presentano

come “contenitori di geni” morti, senza alcuna vitalità; nel momento

in cui entrano nella cellula, però, si confondono con essa, perdendo la

loro individualità e iniziando una frenetica attività biologica. Quando

un virus si trova al di fuori della cellula prende il nome di “virione”.

Virions can have a wide variety of shapes, even very fancy, but

roughly they consist of a ribonucleic acid (DNA or RNA), inside a

shell called “capsid”, made of one repeated protein. Some viruses

have a lipoproteic or glicoproteic membrane around the capsid called

envelope. The envelope is a piece of the cellular membrane taken off

by newborn virions as they go out of the cell. This gives viruses their

high specificity (they have species-specificity, one virus infects only

one or at least two species, and tissue-specificity, i.e. they infect a

specific type of organ or tissue) and works like a “disguise”: many

virus can enter the cell without being “intercepted” immediately tanks

to it indeed. The envelope is fixed to the capsid by membrane

proteins, and between them there is a solutions that protects the

structure from bumps and isolate it from temperature variations.

I virioni presentano una grande varietà di forme, anche molto

fantasiose, ma approssimativamente sono tutti composti da un acido

ribonucleico (DNA o RNA), contenuto in un involucro chiamato

“capside”, fatto da una sola proteina che si ripete. Alcuni virus hanno

una membrana lipoproteica o glicoproteica che avvolge il capside e

che pertanto prende il nome di “pericapside”. Il pericapside è una

parte della membrana della cellula che viene strappato via dai virioni

appena formati al momento della fuoriuscita. Questo conferisce ai

virus la loro altissima specificità (sono specie-specifici , selettivi in

base alla specie, e tessuto-specifici, infettano solo determinati organi e

tessuti) e funge da “travestimento”: grazie ad esso, infatti, molti virus

riescono a penetrare nelle cellule senza essere “intercettati”

immediatamente. Il pericapside è fissato al capside da delle proteine

di membrana, e tra di essi è presente un liquido che protegge dagli urti

e isola termicamente la struttura.

3

4

Two ways of replicating

Due modi per replicarsi

A virus can enter the cell in two different ways: either injecting its

DNA or RNA inside the cell like a syringe (bacteriophages) or by

endocytosis. When it is captured by a bubble the virus can be released

into the cell or activate a ruthless process: once in the bubble, it is

identified as a foreign body, so a lysosome activates; however, as the

lytic enzymes are about to take action, the virus releases “counterenzymes” which inactivate the ones of the cell and dissolve the

bubble, so that the pathogen move through the cytoplasm.

Il virus può entrare nella cellula in due modi diversi: o iniettando il

suo materiale genetico nella cellula come una siringa (batteriofagi o

fagi) o per endocitosi. Quando viene inglobato nella vescicola il virus

può essere liberato nella cellula o può mettere in atto un meccanismo

che definiremmo “perverso”: una volta inglobato nella vescicola, esso

viene riconosciuto come un agente estraneo e quindi un lisosoma si

prepara ad entrare in azione; tuttavia, appena gli enzimi litici

cominciano a digerire il primo strato del pericapside o del capside, si

liberano dei “contro-enzimi” che inattivano quelli della cellula e

addirittura sciolgono la membrana vescicolare e si liberano nel

citoplasma.

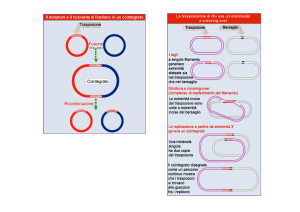

Once inside the cell, viral genome can take two different courses: it

either can replicate immediately or it can insert into cellular DNA and

keep quiescent as a “provirus”. The provirus replicates as the cell

enters meiosis and it can be activated by stress, chemicals or

radiations. When the virus is activated, it tears away from the

chromosome and starts replicating through the viral mechanism.

The first process is called lytic cycle, the second one is the lysogenic

cycle.

A weird fact is that in human DNA there are lots of inactive viral

genes that cannot activate anymore. Once they may have caused

mutations (which are the “vehicle of evolution”) or may have been the

responsible of terrible diseases, but now they are harmless.

Una volta entrato nella cellula, il genoma virale può seguire due

percorsi differenti: può replicarsi immediatamente prendendo il

controllo della cellula o può inserirsi nel DNA cellulare e rimanere

quiescente (“a riposo”) trasformandosi in pro virus e replicandosi

insieme alla cellula stessa, fino a quando non sarà attivato da stress,

sostanze chimiche o radiazioni e si staccherà dal cromosoma cellulare

per replicarsi (excisione). Il primo processo si chiama ciclo litico,

mentre il secondo è definito ciclo lisogeno.

È impressionante sapere che nel DNA umano ci sono molti geni virali

che non possono più essere attivati. Un tempo essi potrebbero aver

causato mutazioni (che sono il “veicolo dell’evoluzione”) o

potrebbero essere stati responsabili di malattie pericolose, ma adesso

sono innocui.

5

6

DNA and RNA viruses

Virus a DNA e ad RNA

The Baltimore classification divides viruses into seven different

classes:

La classificazione di Baltimore suddivide i virus in sette classi

differenti:

1234567-

dsDNA viruses (double stranded DNA)

ssDNA viruses (single stranded DNA)

dsRNA viruses (double stranded RNA)

ssRNA + viruses (positive single stranded RNA)

ssRNA – viruses (negative single stranded RNA)

ssRNA retroviruses

dsDNA retroviruses (this group is often omitted and included

in the first one)

The life of a normal cell is regulated by the DNA-RNA-protein

succession, the so called “central dogma of molecular biology” (but

today it is not a dogma anymore, it is just a catchphrase as Francis

Crick stated). When retroviruses infect cells, they synthesize DNA

from their little quantity of RNA through an enzyme called “inverse

transcriptase” and inserts it into cellular DNA. They are called

“retrovirus” due to this “reverse” process.

1234567-

Virus a dsDNA (DNA a filamento doppio)

Virus a ssDNA (DNA a filamento singolo)

Virus a ds RNA (RNA a filamento doppio)

Virus a ssRNA + (RNA a filamento singolo positivo)

Virus a ssRNA – (RNA a filamento singolo negativo)

Retrovirus a ssRNA (RNA a filamento singolo)

Retrovirus a dsDNA (DNA parziale a filamento doppio;

questo gruppo tuttavia è spesso omesso e compreso nel primo).

La vita di una cellula normale è determinata dalla catena DNA-RNAproteina, il cosiddetto “dogma centrale della biologia” (che oggi di

dogma non ha più niente, ma è solo una “frase ad effetto” come ha

affermato Francis Crick). Quando un retrovirus infetta una cellula,

produce DNA dalla sua piccola quantità di RNA attraverso un enzima

chiamato “trascrittasi inversa” e lo inserisce nel DNA della cellula.

Proprio a causa di questo processo “a ritroso”, questi virus sono detti

“retrovirus”.

7

Some interesting viral diseases

•

Herpesviridae – the

members of this group

are known because

they lie dormant after

the first infection

(most of them in the

trigeminal nerve) and

can activate even

several years due to stress, temperature variations, radiations

and illnesses which may disturb the immune system (even a

fever). The most known members are from the first group, the

so called “α-Herpesviridae”. They cause lips and genital

herpes (HHV-1 and HHV-2) and varicella (HHV-3). The

second infection of HHV-3 leads to herpes zoster, better

known as “shingles”, and that is why this virus is also called

VZV (Varicella-Zoster Virus).

Alcune malattie interessanti causate dai virus

•

Herpesviridae – i componenti di questo gruppo hanno la

caratteristica di rimanere latenti dopo la prima infezione (per

lo più nel nervo trigemino) e possono attivarsi anche dopo

diversi anni a causa di stress, variazioni di temperatura,

radiazioni e malattie che possono causare scombussolamenti

nel sistema immunitario (anche una febbre). I membri più

conosciuti appartengono al primo gruppo, quello dei cosiddetti

“α-Herpesviridae”. Essi causano l’herpes labiale e genitale

(HHV-1 e HHV-2) e la varicella (HHV-3). Il riattivarsi

dell’HHV-3 provoca l’herpes zoster, conosciuto meglio come

“fuoco di

sant’Antonio”, ed

è per questo

motivo che tale

virus si chiama

anche VZV

(Varicella-Zoster

Virus).

8

•

Ortomyxoviridae – it is a big viral family whose members

cause influenza. The majority of influenza viruses is carried by

birds and infects pigs and humans. That is why the virus is

unstable: while it is carried, it modifies two membrane

proteins – the HA protein (hemoagglutinine) and the NA

(neuraminidase) – which give the name to the influenza

(H1N1, H5N1, H3N8…). New influenza virus are born and

other disappear every year, and that is the reason why vaccines

work only in the 87% of the cases. Vaccines are “cocktails” of

different kinds of influenza viruses from the previous years,

which are inactivated or weakened, grown in sterilised chicken

eggs or built in laboratory.

•

Ortomyxoviridae – è una grande famiglia virale i cui membri

causano l’influenza. La maggior parte dei virus influenzali

utilizza come veicolo gli uccelli e infetta maiali e uomini.

Proprio per questo motivo il virus dell’influenza è mutevole:

durante il “trasporto”, esso modifica due proteine di membrana

– la proteina HA (emoagglutinina) e la proteina NA

(neuraminidasi) – che danno il nome all’influenza (H1N1,

H5N1, H3N8…). Ogni anno nascono nuovi tipi di virus

influenzali e se ne estinguono altri, ragion per cui i vaccini

influenzali funzionano solo nell’87% dei casi. I vaccini infatti

rappresentano un “cocktail” di ceppi virali degli anni

precedenti, inattivati o indeboliti, coltivati in uova di gallina

sterilizzate o assemblati in laboratorio.

9

•

Flaviviridae – the majority of viruses causing hemorrhagic

fevers like yellow fever and dengue belong to this group.

These diseases are common in tropical areas because they

spread through ticks and mosquitos. In these cases the diseases

are not caused by the virus itself but it is a sort of lethal

“misunderstanding”: an individual suffers only high fever and

pain the first time he/she is infected by a dengue virus, e.g.

DEN-1, but these symptoms are not deadly. At the second

infection the situation is very dangerous though: there is a

wide range of dengue virus, with some

similarities but lots of differences – so it

is almost impossible to be infected twice

by the same virus. Once in the body, the

new virus – for example DEN-2, is

attacked by antibodies. They do not

eliminate the virus though, but just stick

to it, allowing the pathogen to reach

every cell of the body through the

immune system with devastating

consequences.

•

Flaviviridae - a questo gruppo appartiene la maggior parte dei

virus che causano le febbri emorragiche, come la febbre gialla

e la dengue. Queste malattie sono comuni nelle zone tropicali

perché utilizzano come vettori zecche e le zanzare. In questo

caso i sintomi non sono causati dal virus in sé, ma si tratta di

un “malinteso” che risulta letale: la prima volta che un

individuo viene infettato da un virus dengue, che chiamiamo

per esempio DEN-1, presenta soltanto febbre alta e dolori ,

sintomi in ogni caso non mortali. La seconda volta che un

individuo è infettato la situazione diventa molto

pericolosa: esiste una grandissima varietà di

virus dengue che presentano qualche analogia

ma moltissime differenze – quindi è

difficilissimo in termini statistici essere colpiti

due volte dallo stesso virus. Una volta penetrato

nell’organismo, il nuovo virus – per esempio

DEN-2 – è attaccato dagli anticorpi. Tuttavia

essi non distruggono il patogeno, ma

semplicemente si attaccano ad esso,

consentendogli di raggiungere tutte le cellule

del corpo attraverso il sistema immunitario, con effetti

devastanti.

10

AIDS: A NEW PLAGUE

AIDS is often regarded as the 20th century black death, because it

reminds of the plague epidemic which spread across Asia and Europe

between 1347 and 1351. Plague is the stereotype of a destroying

epidemic, but today AIDS is even more frightening: differently from

plague or common cold, AIDS may lie dormant for years before

causing the first symptoms and in this way the number of cases and

the death toll will continue rising for years, especially in poorer

nations.

The name

AIDS means “Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome”. This is one

of the most complicated names in the history of medicine and means

that the disease is characterized by several clinically recognizable

features, signs and symptoms that occur together (“Syndrome”), all of

which come from a weakening of the immune system (“Immune

Deficiency”) caused by a transmittable pathogen (“Acquired”).

AIDS: UNA NUOVA PESTILENZA

L’AIDS è spesso considerato la “morte nera” del XX secolo, perché

richiama alla mente l’epidemia di peste che si diffuse dall’Asia

all’Europa tra il 1347 e il 1351. La peste è lo stereotipo dell’epidemia

distruttrice, ma oggi l’AIDS è ancora più spaventoso: a differenza

della peste o del raffreddore comune, l’AIDS può rimanere quiescente

per anni prima di causare i primi sintomi e per questo motivo i casi e

il tasso di mortalità continueranno a salire, specialmente nei Paesi più

poveri.

Il nome

AIDS significa “Sindrome dell’Immunodeficienza Acquisita”. Questo

nome è tra i più complicati della storia della medicina e significa che

la malattia è caratterizzata da una serie di condizioni, manifestazioni e

sintomi che concorrono (“Sindrome”), tutti provenienti da un

indebolimento del sistema immunitario (“Immunodeficienza”) causato

da un patogeno trasmissibile (“Acquisita”).

11

The discovery

La scoperta

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) was discovered independently

in 1983 by Luc Montaignier in Paris and by Robert Gallo in the USA.

This double-discovery caused a dispute on who was worth the Nobel

prize. Eventually Montaigner received it and Gallo is regarded as the

co-discover, although he and his team developed scientific methods

that made the discovery possible. HIV is a mutation of the SIVcpz

(Simian Immunodeficiency Virus of chimpanzee). However the

moment when the virus passed from

monkeys to humans is not clearly

known: it is thought it happened

between the end of the 19th century

and the early 20th in Africa due to the

contact with infected blood during

chimpanzee hunting or because of the

habit of eating chimpanzee raw meat.

The first certain case dates back to a

blood sample taken from an African

man in 1959 and analysed in the

1980s, while it is believed that it has

spread in the USA in the 1960s during the so called “sexual

revolution”.

L’HIV (Virus dell’Immunodeficienza Umana) fu scoperto

indipendentemente nel 1983 da Luc Montaignier a Parigi e da Robert

Gallo negli Stati Uniti. La doppia scoperta causò una disputa su chi

avrebbe meritato il premio Nobel. Alla fine lo ricevette Montaigner e

Gallo viene considerato il co-scopritore, sebbene lui e il suo team

abbiano sviluppato i metodi scientifici che hanno reso possibile la

scoperta. L’HIV è una mutazione del SIVcpz (Virus

dell’Immunodeficienza delle Scimmie, specie scimpanzé). Tuttavia

non si sa con esattezza quando

avvenne il passaggio del virus dalle

scimmie all’uomo: si pensa tra la fine

dell’Ottocento e i primi decenni del

XX secolo in Africa a causa del

contatto con sangue infetto durante le

battute di caccia agli scimpanzé o in

seguito all’usanza di cibarsi delle

carni crude di questi animali. Il primo

caso accertato risale ad un campione

di sangue prelevato da un uomo in

Africa nel 1959 e analizzato negli anni Ottanta, mentre si ritiene che

sia stato diffuso negli Stati Uniti negli anni Sessanta durante la

cosiddetta “rivoluzione sessuale”.

12

Breaking down the walls

Abbattendo le mura

Many microorganisms are harmless for a normal person – we get in

touch with billions of bacteria, viruses and toxins without damages

indeed – but are lethal for HIV-positives: the virus damages the

immune barrier allowing the so called “opportunistic infections” to hit

every part of the body. They can be common diseases but also rare

cancers, like Kaposi’s Sarcoma.

La maggior parte dei microorganismi sono innocui per un individuo

normale - basti pensare che ogni giorno noi entriamo in contatto con

miliardi di batteri, virus e tossine senza riportare danni - ma risultano

mortali per chi è HIV-positivo: il virus danneggia la barriera

immunitaria permettendo alle cosiddette “infezioni opportunistiche”

di colpire ogni parte del corpo. Esse possono essere malattie comuni

ma anche tumori rari, come il Sarcoma di Kaposi.

The immune system attacks the virus as it enters the body, so the

patient just suffers “soft” symptoms like a normal fever. The virus is

not defeated though, but continues replicate faster and faster. Many of

the newborn viruses are destroyed, but many other infect every cell of

the body having a “CD4” membrane protein, i.e. helper-T cells of the

immune system (the “generals” among the cells of the immune

system, which “give directions” to the other cells – killer T, B

lymphocytes and antibodies – what and how to attack). When the

virus is in the cytoplasm, it synthesises a DNA molecule from its

RNA through inverse transcriptase and inserts into the nucleus

becoming a provirus. When HIV activates and starts replicating,

helper T lymphocytes die because of stress or collapse or – when it is

not the virus itself that destroys it – they are identified as infected and

eliminated through apoptosis (cells “programmed suicide”). After the

provirus period, the destruction of the immune system cannot be

stopped and leads to the patient’s death because of the many

opportunistic infections.

Appena il virus entra nel corpo, il sistema immunitario lo attacca, così

il soggetto soffre soltanto sintomi leggeri come una normale febbre.

Tuttavia il virus non è sconfitto, ma continua a replicarsi sempre più

velocemente. Molti dei nuovi virus vengono distrutti, ma molti altri

infettano ogni cellula del corpo che presenti una proteina di membrana

chiamata “CD4”, cioè i linfociti T-helper (i “generali” del sistema

immunitario, che “danno indicazioni” alle altre cellule – i linfociti Tkiller, i linfociti B e gli anticorpi – cosa e come attaccare). Quando il

virus è nel citoplasma, attraverso la trascrittasi inversa, sintetizza una

molecola di DNA a partire dal proprio RNA e la inserisce nel nucleo

della cellula rimanendo latente. Nel momento in cui l’HIV si riattiva e

comincia a replicarsi, i linfociti T-helper muoiono per stress o collasso

o, quando non è il virus a distruggerle, vengono identificate come

difettose e eliminate attraverso l’apoptosi (“suicidio programmato”

delle cellule). Passato il periodo di latenza, la distruzione del sistema

immunitario è irreversibile e porta alla morte per le molte infezioni

opportunistiche.

13

14

HIV: transmission, prejudices and prevention

HIV: trasmissione, pregiudizi e prevenzione

HIV is transmitted through body fluids (blood and sexual fluid but not

tears or saliva), so in three main ways:

L’HIV si trasmette attraverso i fluidi corporei (sangue e fluidi

sessuali, ma non lacrime e saliva), quindi attraverso tre vie principali:

•

Through sexual intercourse, both homosexual and

heterosexual

• through blood, sharing infected syringes or having

contacts or – worst – transfusions with infected blood

• from mother to child, during the birth or the lactation

Since the first victims of AIDS male

homosexuals, today many people

believe that this disease only hits

isolated groups (not only gays but

also prostitutes and drug addicts who

share infected needles). Those

prejudices may cause shame of

talking about the problem with the

society or with the doctors too.

Heterosexual intercourse is the most

common way to transmit the virus though, followed by infected

needles and transfusions (even if today we have a decrement of

infected transfusions).

•

•

•

Per via sessuale, sia nei rapporti eterosessuali che in quelli

omosessuali

Per via ematica, attraverso lo scambio di siringhe, contatti – o

peggio – trasfusioni con sangue infetto

Per via verticale materno-fetale, cioè dalla madre al figlio al

momento del parto o durante l’allattamento.

Poiché le prime vittime

dell’AIDS sono stati

omosessuali, oggi

molte persone

ritengono che questa

malattia colpisca solo

gruppi isolati (non solo

gay, ma anche

prostitute e tossicodipendenti che condividono le siringhe). Questi

pregiudizi potrebbero portare vergogna a parlare del proprio problema

con la società o anche con i medici. Tuttavia, i rapporti eterosessuali

sono la via di trasmissione della malattia più comune, seguiti dagli

aghi infetti e dalle trasfusioni (quest’ultime in notevole calo).

15

What can be done against AIDS?

Cosa può essere fatto contro l’AIDS?

Today, nearly 32 years after the discovery of HIV, it is still impossible

to defeat this disease. So far only two cases of healing are certain.

A distanza di quasi 32 anni

dalla scoperta del virus

HIV è ancora impossibile

guarire da questa malattia.

Finora infatti sono solo due

i casi di guarigione

confermati.

The first case is an

example of “custom

medicine”, the last

frontier in medicine.

The HIV-positive

Timothy Brown

received a bone

marrow transplant from a patient with a rare mutation in 2007 in

Berlin, and it allowed him to defeat the virus.

The second case is different: it is about a baby girl who was born

HIV-positive in 2010 and was treated with a drug cocktail which

highly weakened HIV for two years and a half. Today the child, who

has stopped the cure for unknown reasons, is constantly observed and

does not reveal any AIDS symptom, but only a few traces of viral

DNA and RNA in her blood. This case may be useful to develop a

therapy against HIV both in children HIV-positive-born and adults.

The main cause of the resistance of HIV is due to his extremely high

mutation toll: it has an average of a mutant virus over the 1011

produced every day. Among those

Il primo caso è un esempio

di “medicina personalizzata”, l’ultima frontiera in campo medico. A

Berlino Timothy Brown, paziente sieropositivo, ha subito nel 2007 un

trapianto di midollo osseo da un paziente affetto da una rara

mutazione genetica che gli ha consentito di eradicare completamente

il virus.

Diverso è il secondo caso: si tratta di una bambina nata nel 2010 e

trattata per due anni e mezzo con un cocktail di farmaci che ha ridotto

l’HIV ai minimi termini. Attualmente la bambina, che ha sospeso la

cura per ragioni sconosciute ed è monitorata costantemente, non

manifesta i sintomi dell’infezione ma presenta nel sangue poche

tracce di DNA e RNA virale. Questo caso potrebbe aprire la strada

alla cura dell’HIV sia nei bambini nati sieropositivi che negli adulti.

La principale causa della resistenza dell’HIV è dovuta al suo

elevatissimo tasso di mutazione: in media una particella virale

mutante in 1011 prodotte ogni giorno. Fra tutte queste

16

mutations that happen day after day for several years, it is certain that

many of them make HIV resistant to every kind of therapy. Many

efforts have been done to inactivate inverse transcriptase. This

enzyme is very important for HIV and the other retroviruses and can

be attacked strongly because nothing in human body may be

damaged. Today, in spite of many antiretroviral therapies, defeating

HIV is impossible: one can only live together with AIDS, but not heal.

HAART (Highly Active Anti Retroviral Therapy) has risen up HIVpositives’ life expectancy, from 20 or 40 years to a maximum of over

60, but to heal a patient 50-60 years of HAART are necessary, clearly

a improbable possibility,

mutazioni, che avvengono giorno dopo giorno per diversi anni, è

inevitabile che ce ne siano alcune in grado di rendere l’HIV resistente

ad ogni terapia. Gli sforzi maggiori sono stati finalizzati a bloccare

l’azione della trascrittasi inversa. Questo enzima – infatti – è di

fondamentale importanza nell’HIV e negli altri retrovirus e può essere

attaccato anche con violenza poiché non presenta equivalenti che

potrebbero essere danneggiati nell’essere umano. Tuttavia, nonostante

le terapie antiretrovirali oggi esistenti, sono nulle le possibilità di

debellare il virus: con l’AIDS si può convivere, non guarire. La

HAART (Terapia Antiretrovirale ad Elevata Efficacia) ha alzato l’età

media dei sieropositivi dai 20 o 40 anni fino ad un limite oltre i 60, ma

per guarire un individuo servono 50-60 anni di trattamento, una

prospettiva non realistica.

17

How to behave?

Come comportarsi?

AIDS does not have any

geographical, social or

economic borders. The

whole world population

can be infected. After

the infection, the virus

cannot be defeated: the

only solution is

preventing, starting from

information and sensitisation. OMS synthesised the three main steps

for prevention with the “ABC rule”:

L’AIDS non conosce

confini di ogni sorta:

geografici, sociali o

economici. Tutta la

popolazione sessualmente

attiva è esposta al rischio

contagio. Una volta

contratto il virus è

impossibile guarirne:

l’unica soluzione è la prevenzione, partendo innanzi tutto dalla

conoscenza e dalla sensibilizzazione, in particolare dei giovani.

L’OMS ha sintetizzato i tre pilastri della prevenzione nella “regola

ABC”:

A. Abstinence (from an unsure sexual intercourse)

B. Be faithful (and avoid promiscuous sex)

C. Condom

The ABC rule may sound easy to follow to western people, but it is

not the same in nations where poverty, ignorance and alienation are

widespread, where sex is a taboo and there is no freedom in choosing

sexual partners, especially for women. That is the reason why many

non-governmental organisations are working in those countries to

awaken the population to make small vital changes.

A. Abstinence (nel dubbio, astieniti da un rapporto sessuale)

B. Be faithful (sii fedele, evita i rapporti occasionali)

C. Condom (usa il preservativo).

La regola ABC può apparire semplice agli occhi di noi occidentali, ma

non è facile da seguire nei Paesi in cui povertà, ignoranza ed

emarginazione sono diffuse, dove il sesso è un argomento strettamente

tabù e la libertà di scelta dei rapporti sessuali è limitata, soprattutto

per le donne. Non a caso in questi Paesi diverse associazioni non

governative si stanno adoperando per sensibilizzare la popolazione

affinché prenda precauzioni compiendo piccoli cambiamenti che

salverebbero le loro vite.

18

EPILOGUE

CONCLUSIONE

The one about viruses is a very interesting subject. They are

fundamental to study closely the processes of host cells, to develop

new therapies modifying them to be used as “carriers” . We live

surrounded by viruses, extremely small particles which use such

“ruthless” strategies which cannot be beard neither in the mind of the

worst pirates, predators and movie or videogames evils. It is all about

natural selection though: the only aim of the viruses is to replicate,

they ignore what their hosts are. However, among their hosts, humans

cannot be as ignorant as viruses are: they may lose the “run for

evolution”.

I virus sono un argomento molto interessante: sono fondamentali per

studiare da vicino i meccanismi delle cellule ospiti, per sviluppare

nuove cure modificandoli e utilizzandoli come “vettori”. Noi viviamo

circondati da virus, minuscole particelle che utilizzano meccanismi

“perversi” a cui non penserebbero neppure i peggiori pirati, predatori

e cattivi da film o videogiochi. Tuttavia si tratta solo di selezione

naturale: l’unica missione dei virus è quella di riprodursi, sono

totalmente indifferenti ai loro ospiti. Fra tutti, però, l’uomo non può

rimanere indifferente ad essi: rischierebbe in tal modo di rimanere

indietro nella “corsa all’evoluzione”.

I thank my Science teacher Ermelinda Marino who gave me the

opportunity of writing this report and provided to me some

information about viruses and AIDS. I also thank Dr. Giovanni Maga

– the First CNR Researcher and professor in DNA Enzymology &

Molecular Virology Unit at the university of Pavia. I become fond of

viruses by reading his book “Occhio ai virus”, which describes the

world of these parasites through a very simple language and which I

used to write this relation.

Ringrazio la mia professoressa di scienze, Ermelinda Marino, che mi

ha dato l’opportunità di scrivere questa relazione e mi ha fornito del

materiale sui virus e sull’AIDS. Ringrazio anche il dottor Giovanni

Maga – primo ricercatore del CNR e professore del dipartimento di

enzimologia della replicazione DNA e di virologia molecolare

all’università di Pavia. Mi sono appassionato ai virus leggendo il suo

libro “Occhio ai virus”, che descrive il mondo di questi parassiti con

un linguaggio molto semplice e che ho usato per scrivere questa

relazione.

Stefano Cacciatore, IV A

A.S. 2013/2014

Agrigento 27/03/2014

Stefano Cacciatore, IV A

A.S. 2013/2014

Agrigento 27/03/2014

19

![Lezione 15 Virus [modalità compatibilità]](http://s1.studylibit.com/store/data/000771737_1-84b1cca561c5813066d1b76125338a98-300x300.png)