caricato da

common.user20973

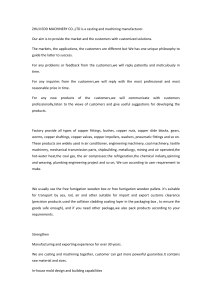

Drawing in Aphasia: Interactive Communication

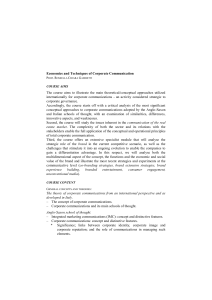

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/220107719 Drawing in aphasia: Moving towards the interactive Article in International Journal of Human-Computer Studies · October 2002 DOI: 10.1006/ijhc.2002.1018 · Source: DBLP CITATIONS READS 20 3,864 1 author: Carol Sacchett University College London 14 PUBLICATIONS 422 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE All content following this page was uploaded by Carol Sacchett on 10 September 2018. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Interactive drawing in Aphasia DRAWING IN APHASIA: MOVING TOWARDS THE INTERACTIVE. Carol Sacchett, Speech & Language Therapist Research Fellow Address for correspondence, proofs and reprints: Department of Human Communication Science University College London Chandler House, Wakefield Street London, WC1, UK. e-mail: [email protected] Interactive drawing in Aphasia DRAWING IN APHASIA: MOVING TOWARDS THE INTERACTIVE. Carol Sacchett Department of Human Communication Science, University College London, Chandler House, Wakefield Street, London, WC1, UK. e-mail: [email protected] Running title: Interactive Drawing in Aphasia Summary This paper reviews the literature on the use of drawing to communicate by people whose language is restricted due to aphasia. The advantages of drawing over other forms of non-verbal communication for this population are detailed, followed by discussion of different approaches to communicative drawing with reference to descriptive reports, treatment studies and review papers. The two main approaches differ in their view of drawing either as an alternative to speech or as an augmentative tool in multimodal communication. In the former approach the focus is on drawing skill or quality. Successful transmission of messages is the goal, and this depends on the production of recognisable drawings. In contrast, in the latter approach quality of drawings is secondary to its value as an interactive medium. The focus is on interpersonal aspects of communication and drawing is used alongside other modalities as a medium of social connectedness. The main principles of interactive drawing are discussed with examples from recent therapy studies. These are: the importance of drawing “economically” rather than producing “good” drawings; the contribution of the communication partner in facilitating, developing and maintaining a shared interaction; and the importance of using interactive drawing within natural communication contexts, in particular conversation. Interactive drawing in Aphasia Keywords: aphasia, drawing, interaction. Introduction Aphasia is an acquired disorder of language resulting from brain damage, most commonly following stroke or head injury. Whilst there are no official figures for the incidence and prevalence of aphasia in the UK, its incidence is estimated at 20,000 new cases per annum. At any given time there are an estimated 200,000 adults living with aphasia in the UK1 . The term aphasia is an umbrella term which covers a variety of language difficulties and a range of severity. Most people with aphasia will have some impairment in all language modalities: speaking, understanding, reading and writing, but the form these impairments take and the degree to which each modality is affected will vary. At the more severe end of the scale, aphasia can result in almost total loss of the ability to speak or write. Speech is restricted to one or two words or a few phrases which are repeatedly used. Writing may be limited to attempts at single words, frequently misspelt. In addition, auditory and reading comprehension are reduced to understanding one or two key words in a sentence. With the help of pragmatic, visual and contextual cues, this may be enough to allow comprehension of simple conversation. These deficits are attributable to a number of different processing impairments. Semantic abilities may or may not be affected. Syntactic abilities and access to language symbols in the mental lexicon are invariably compromised. Crucially, however, most of these individuals, even those with severe aphasia, retain their previous intellectual abilities or their “conceptual integrity of thought” (Lyon 1995a). 1 Figures obtained from Speakability, a UK charity which aims to promote public awareness of aphasia and offers services to people with aphasia Interactive drawing in Aphasia Typically therapy for people with severe aphasia focuses on developing non-verbal channels of communication to compensate for a reduction in language ability (Green 1982, Davis & Wilcox 1985). Prior to the interest in communicative drawing, the mainstay of this kind of augmentative communication was picture and word communication boards, where individuals pointed to their basic needs. This type of communication aid is necessarily limited by its “prescriptiveness”. One can only communicate about things that occur on the board, thus the creativity and versatility of communication is lost. Similarly attempts to promote gestural communication have met with limited success. At best individuals have achieved only a small repertoire of meaningful gestures, once again restricting their communication to the basic needs level. In comparison with other forms of communication, drawing has two main benefits. Firstly, as information is represented iconically, it does not require an ability to process arbitrary symbols, a skill which is often compromised in severe aphasia. Access to visual or graphic forms, however, is usually spared. Secondly drawing provides a fixed, permanent record of an exchange, amenable to modification by both parties. Attempts at clarification would therefore have a visible, concrete referent, thus would not rely on intact short-term memory or sequential ability, unlike more transient forms of communication (for example speech or gesture). Clarification of graphic messages will be discussed in more detail later in this paper. At this stage it is important to state that accounts of communicative drawing in the aphasia literature generally describe interactions in which one participant has aphasia while the other does not. Thus communicative drawing usually takes place within the context of a “Total Communication” approach (Green 1982; Pound, Parr, Lindsay & Woolf 2000), which involves flexible use of a number of modalities inc luding speech, Interactive drawing in Aphasia writing and gesture. Whilst drawing may be the modality of choice for the person with aphasia, s/he may and the communication partner will undoubtedly make use of other modalities during an exchange. Drawing in aphasia Drawing in aphasia has attracted the interest of clinical researchers for a variety of reasons. From a neuropsychological perspective, the focus of study has been analysis of drawing impairments in aphasia. Attempts have been made to pinpoint the causes of drawing dysfunction following brain damage, in order to increase understanding of higher cortical processing (Warrington, James & Kinsbourne 1966, Benton 1985, Gainotti, Silveri, Villa & Caltagirone 1983, Swindell, Holland, Fromm & Greenhouse 1988). In contrast, preserved graphic abilities in aphasia have inspired interest in drawing as a means of self-expression, particularly in terms of addressing psychological and emotional trauma via art therapy (Pachalska 1990, Kaczsmarek 1991). Finally the subject of study amongst those involved in aphasia rehabilitation has been the value of drawing as a means of enhancing communication. This third aspect of drawing in aphasia will be the focus of this paper. Different approaches to communicative drawing will be discussed, with reference to both descriptive accounts of individuals with aphasia and experimental (treatment) studies documenting improvements in drawing to communicate. A key issue is in the measurement of communicative success. Whilst some studies focus on improvements in drawing quality, others measure success in terms of the transfer of information between partners in the communication dyad. More recently, reflecting current trends in aphasia rehabilitation, a move from purely communicative drawing to more interactive drawing has been advocated, in which the transfer of information takes a secondary role to the Interactive drawing in Aphasia interpersonal function of communication. (Lyon 1995a, 1995b; Sacchett, Byng, Marshall & Pound 1999). Drawing to communicate In his review of drawing as a communication aid in aphasia, Lyon (1995a) identifies two distinct approaches. The first, which views drawing as a substitute for language, focuses on the ability of the person with aphasia to produce recognisable “content units”. Treatment involves improving the quality of the drawings produced and independence as a communicator is often the goal. The burden of communication therefore rests with the person with aphasia. The second approach views drawing not as an alternative to language, but rather as an augmentative tool. The emphasis is on the exchange of information and ideas. The quality of the drawings produced is secondary to their communicative value. This latter approach acknowledges the crucial role played by the interactant in deriving meaning from the drawings produced, even if they are not immediately recognisable. Early descriptive accounts of the use of drawing to communicate in aphasia tend to focus on the abilities of the aphasic individual, with little reference to the communicative context or interactant. The most well-known account is of the graphic illustrator, Sabadel (Pillon, Signoret, Van Eeckhout & Lhermitte 1980, Lorant & Van Eeckhout 1980), who developed severe aphasia and right hemiplegia following a stroke. Shortly after his stroke he began to spontaneously draw objects he could not name. He progressed to drawing detailed stories and continued to refine his drawing skills even some years after the onset of aphasia, to the point where he was able to illustrate a book about his experiences. Interactive drawing in Aphasia Gourevitch (1967) describes an 82 year-old retired art professor who, after developing Wernicke’s (fluent) aphasia2, was persuaded to communicate with drawings and strip cartoons. These two cases are unusual in that they describe professionally trained artists. However, descriptive studies exist which document the ability of people with no pre-morbid artistic training to use drawing to communicate events and stories (Ajuriaguerra & Hecaen 1960, Hatfield & Zangwill 1974). A similar focus on the drawing ability of the person with aphasia is evident in a number of more recent therapy studies, which aim to improve the “recognisability” of the drawings produced. These studies take as their basis the body of literature detailing impairments in drawing production in aphasia. Typically, people with aphasia produce drawings which are lacking in detail (Warrington et al 1966, Gainotti & Tiacci 1970, Swindell et al 1988). Thus the contrastive features which distinguish one item from another are often missing and this results in drawings not being easily recognised. Therapy therefore concentrates on training the person with aphasia to produce recognisable drawings and effectiveness of therapy is measured in terms of how well or quickly the drawings or messages are recognised or interpreted by naive judges. Trupe (1986), for example, describes therapy with fifteen people with severe aphasia. The first part of the therapy programme consisted of tracing and copying single objects, and finally drawing those same objects once they had been removed from view. Thus the subjects received repeated practice in drawing a small repertoire of individual items. In the second part of the programme, subjects progressed to conveying “complex 2 Wernicke’s aphasia, sometimes referred to as jargon aphasia, is characterised by fluent ‘empty’ speech, lacking in content whilst maintaining syntactic form. Naming abilities are severely limited and often characterised by the production of neologisms. Auditory and reading comprehension are usually severely impaired. Interactive drawing in Aphasia concepts” via drawing. Little detail is given about these complex concepts but, since they were all produced from a picture stimulus, we can assume them to be concrete rather than abstract concepts. As an outcome Trupe reports that all participants learned to convey concrete messages in structured treatment tasks. However the measures used to chart this improvement are not specified. The measure of success seems to be how far each individual progressed through the therapy programme. Progression relied on consistent, independent and accurate conveying of messages, but how this was judged and by whom is not made explicit. Trupe defines “independent” as requiring “no listener feedback”. Presumably, therefore, the drawings had to be immediately recognisable to be deemed successful. Thus the focus in this study is on the aphasic person as a conveyer of messages. The receiver of these messages is, it seems, at best irrelevant, at worst interfering with independence. Morgan & Helm-Estabrooks’ (1987) treatment programme Back to the Drawing Board (BDB) also targets the drawing skills of the person with aphasia. Here two people with restricted verbal output as a result of aphasia were taught to reproduce single, double and triple panelled cartoons from short term memory. They practised these sketches until their drawings could be recognised by naive interactants. Like Trupe’s study therefore, therapy involved repeated practice on the same items with a view to producing “good” drawings. The measure used in this study differed from Trupe, however. Before and after the therapy period, the participants were required to draw scenes depicting “accidents of daily living” acted out by the clinician. 75% of the post-treatment drawings were judged superior to those produced before therapy. Once again, the criteria used for making this judgement are not specified but the implication is that the quality of the Interactive drawing in Aphasia drawings was being judged independently of their communicative value within an interaction. In contrast to the almost drill-like quality of the previous two therapy studies, Yedor & Kearns (1987) applied a “loose” training technique, Response Elaboration Training (RET) to communicative drawing with one man with Broca’s (non-fluent) aphasia3 . The patient was shown black and white line drawings depicting actions and asked to draw about the picture or what it reminded him of. He was then prompted to expand the amount of content in his drawings by the use of Wh- questions and “naturalistic feedback”. The measure of success was an increase in the number of ”content units” produced i.e distinct aspects of the drawing that conveyed new information. Encouraged by this result and by observed generalisation of drawing to other people and with untrained items, the authors conducted a follow-up study to see if drawing content in natural conversation could also be increased by RET. The stimuli used were short video clips of news broadcasts which then formed the basis for discussion. Once again the number of content units produced increased after therapy and generalisation to different people and settings occurred. This study is of interest because it addresses the key issues of transfer to natural conversation and generalisation. However the measure of success still focused on an improvement in the drawing skills of the person with aphasia i.e the ability to draw content units. There is little mention of the role of the interactant in extracting that content. In addition, improvement is measured quantitatively, rather than qualitatively: it is the number of content units which is the dependent measure. As long as he produced more of them after therapy, then therapy was deemed successful. The 3 Broca’s aphasia is characterised by non-fluent agrammatic speech, consisting of a string of content words not linked by any syntactic form. Auditory and reading comprehension are relatively spared, although there may be some impairment in these modalities. Interactive drawing in Aphasia authors’ conclusion focuses on the independence of the aphasic communicator, citing a shift in the burden of communication from clinician to patient as a successful outcome. Towards interactive drawing This view of communication as a burden to be carried by one or other of the participants in an interaction is at odds with more recent trends in aphasia rehabilitation, which regard communication as a shared responsibility and an opportunity for mutually satisfying encounters (Kagan 1995). Attention is drawn beyond the impairment of aphasia to include the behaviour, responses and communication of others. Therapy therefore aims at improving the skills of the communicative dyad, with emphasis on enabling others to reveal and acknowledge the competence of the person with aphasia (Kagan 1995, Simmons -Mackie 1998). Communicative competence refers to more than simply conveying messages. Simmons-Mackie & Damico (1995) differentiate between transactional and interactional functions of communication. Transactional refers to exchanging information, and the therapy studies described above, with their aim of improving the person with aphasia’s skills at “getting the message across”, can be said to be focusing on transaction. Interactional includes the recognition of the social function of communication as “a mechanism for relating to other people”. For communicative drawing to be effective, both transaction and interaction need to be focused in therapy. Recent therapy studies have recognised this and have combined therapy aimed at improving the communicative value of drawings with therapy focusing on the interactive potential of drawing within a more “natural” communicative context. The main medium of therapy is that of conversation and steps are taken to create the feel and flow of natural conversation. Interactive drawing in Aphasia Recognisability of the drawings produced takes second place to other factors, such as context, shared knowledge, interpreter skills, clarification strategies and so on. Thus the emphasis is not on improving quality or accuracy of the drawings per se., but rather on developing skills and strategies which will facilitate the communicative process. In addition the skills of the interactant become an equal focus of therapy, as the communicative value of drawing depends primarily on the ability of others to derive meaning from the drawings produced, even if they are not immediately recognisable (Lyon 1995 & 1995b, Sacchett & Lindsay 1998, Sacchett et al 1999). Some of these aspects of interactive drawing will be discussed in more detail below, with examples from recent therapy studies. a) Increasing the communicative value of drawings and facilitating interpretation Although accuracy and clarity are not regarded as prerequisites for interactive drawing, there is general acknowledgement that impaired drawing production in aphasia may reduce the communicative potential of the graphic message (Pound et al 2000). As previously discussed many people with aphasia typically omit distinguishing features from their drawings. The over-inclusion of unnecessary, communicatively irrelevant details can also interfere with the efficiency of interaction. Thus in order to achieve interactive drawing, the ability to draw “economically”, in other words including only communicatively relevant details in drawings, has been a focus of treatment in recent studies which aim ultimately to improve interactive drawing. Sacchett et al (1999) describe a treatment programme with seven people with severe aphasia in which, amongst other things, specific steps were taken to promote economic drawing and to use it interactively. At a single-item level attention was drawn to Interactive drawing in Aphasia communicatively relevant distinctive visual features of objects, and participants were required to convey these objects in an interactive drawing context. At a more complex level, in which actions, events, changes or problems were being discussed, the strategy of selecting communicatively significant elements of events and depicting these separately rather than in one simultaneous drawing was found to be useful. Examples of these techniques are given in their Appendix B which details the progress of one of the aphasic participants, GJ. Drawings produced early on in therapy demonstrate improved awareness of distinctive, communicatively relevant features. He later successfully uses strategies such as enlargement of portions of the drawing for emphasis and clarification, crossing parts of the drawing out to indicate negation. By the end of the 12 week therapy period, GJ, who has no spoken or written output and severe auditory processing problems, is able spontaneously to “tell a story” using drawing. The overall message is separated into interpretable “chunks” using a stripcartoon approach, with each panel depicting one key event. Within each panel the event is separated into key elements with direction of movement indicated by arrows and orientation of the figures (Figure 1). Insert Figure 1 here The prime purpose of the above strategies was to improve the communicative value of the drawings produced. Although some of the tasks used to develop the strategies might appear quite structured, the authors stress that they were always used alongside more informal, conversational interactions to effect transfer into everyday contexts. Interactive drawing in Aphasia Refinement of drawing skills was also one feature of the therapy undertaken by Lyon & Sims (1989) to improve the communicative effectiveness of drawings produced by eight “expressively restricted adults” (ERAs). Attention was focused initially on establishing or refining “primary” drawing skills such as form, spatial orientation, detail and perspective. Subjects were then given “salient visual contexts” to draw, such as “You spent the afternoon sleeping in the a hammock in the backyard”. If the drawings produced were not recognisable, verbal and graphic cueing was used to suggest ways in which they could be improved. These cues helped in the development of strategies to clarify the drawings. The final drawings were then used as the basis for an interaction with an interactant trained in facilitative techniques (see below). They found that both the ease of recognition and the communicative effectiveness of the ERAs’ drawings, as rated by two independent judges, improved following therapy. Ward-Lonergan and Nicholas (1998) report on several treatment approaches to developing communicative drawing in a man with chronic global aphasia (2). Like the previous two studies, some time is devoted initially to refining drawing skills using the Back to the Drawing Board technique described earlier in this paper (Morgan & Helm Estabrooks 1987). In comparison to his pre-treatment drawings, which were sketchy and lacking in essential detail, the quality of his post-treatment drawings had improved dramatically. Specifically noted were the elaboration of detail, the ability to depict more abstract concepts and the improved use of orientation. Subsequent therapy was aimed at developing these newly acquired skills in an interactive context, initially in relatively structured tasks and later in unstructured tasks resembling natural conversation (see below). The authors report an increased ability to modify his drawings to enhance communicative effectiveness, such as the use of strategies like enlargement. Interactive drawing in Aphasia These studies, which aim to develop interactive drawing, nevertheless include some therapy to refine drawing skills, in order to make the drawings produced more “transparent” to the interpreter. This aspect of the therapy programmes therefore appears to target transactional drawing, since the purpose is facilitating message transfer. However they differ from previous studies described in that the tasks do not have as an end simply the production of “good” drawings. Indeed in some cases this may even be actively discouraged, since some individuals sacrifice efficiency of communication by spending too much time on the quality of their drawings. This affects the “naturalness” of the exchange, for example by interfering with turn-taking. In addition these therapies focus on strategy rather than skill development. Subjects are encouraged to develop strategies in their drawing production which will enable interactants to interpret the communicative intent of their drawings more easily and more efficiently. Thus only those strategies which will increase the communicative potential of the drawings are targeted. Whilst techniques to facilitate the recognition of drawings may form part of the therapy programme, other strategies serve different communicative purposes. For example, the strategy of enlargement referred to above can serve to emphasise important aspects of the message or to elaborate on a particular theme or topic. Some strategies replace aspects of language which are no longer available to the individual, for example the use of arrows can differentiate between thematic roles in an event i.e. “who-does-what-to-whom”, which poses a particular problem in severe aphasia (Dipper, Black & Chiat, in press). Further examples of such strategies and the communicative functions they serve can be found in Lyon 1995a, 1995b. Interactive drawing in Aphasia The focus on strategy development has the additional benefit of promoting generalisation to spontaneous use and to other communicative arenas. To this end, strategies are transferred to the interactive arena at the earliest opportunity, by means of specific interactive tasks and inclusion in natural conversations. b) The role of the interactant As Lyon (1995b) points out, communicative drawing is not an ability or skill confined to the person with aphasia. Rather it is “a dynamic interplay between interactants from start to finish”. The role of the interactant is placed firmly in the foreground, in the production of a combined picture or message and in the interpretation of messages which are not immediately clear. The importance of training interactants in facilitative techniques is therefore a common feature of therapy programmes aimed at developing interactive drawing. Both Lyon & Sims (1989) and Sacchett et al (1999) included training of family members in their treatment programmes. The aim of training was to develop facilitative techniques for extracting content from or interpreting the drawings produced by the aphasic partner, particularly when they are not immediately recognisable. Examples of such techniques are given in Appendix 1 . In both studies, training took the form of structured observation, modelling, feedback and direct participation in therapy sessions, including encouragement to use drawing themselves. Improvements in the interpretation skills of communication partners was reported by Sacchett et al (see also Sacchett & Lindsay 1998). In the Lyon & Sims study, no such improvements are noted, but it is possible that improved interactant skills contributed to the increased communicative effectiveness Interactive drawing in Aphasia scores, particularly as one variable in determining these scores was time taken for messages to be understood. A fundamental aspect of interactive drawing is the use of drawing by both partners in the exchange (Lyon 1995, Bauer & Kaiser 1995, Sacchett et al 1999). The clinician must use drawing to persuade both the person with aphasia and his/her key communication partners that it is a viable means of communication and to model appropriate strategies and techniques for developing conversations. One way of achieving this is by demonstrating the usefulness of drawing in communication by doing it oneself, thus promoting equal status. Advantages of encouraging the use of drawing by the nonaphasic partner are detailed by Bauer & Kaiser (1995) . It enables relatives to become familiar with some of the problems associated with drawing. It promotes creative participation in the development of techniques of representation and conventionalisation. Relatives can also learn how to use drawing to enhance their partner’s comprehension, structure the conversation and document its results. c) Context and conversation Lyon (1995b) recommends that interactive drawing should always be used within a communicative context. The role of context in aiding interpretation of drawings is discussed by Sacchett et al (1999). They found that drawings produced by people with aphasia were significantly more easy to recognise when shown to naive judges within a context than when presented in isolation. Although this finding is hardly surprising, this reflects how drawings would typically be produced in a natural interaction. Interactive drawing in Aphasia In the Lyon & Sims (1989) study, communicative context is provided by the clinician, who describes a real-life, but hypothetical situation for the person with aphasia to draw. In addition, in common with the other two studies, context is frequently provided through conversation. Conversation, as a collaborative social activity, is by necessity interactive in nature. By using drawing in a conversational context, the person with aphasia is able to participate as an equal partner in communication. Also, conversational drawing can facilitate the transfer of skills from the clinical arena to the person’s everyday environment. Generalisation of interactive drawing to non-clinical environments was reported by both Ward-Lonergan & Nicholas (1998) and Sacchett et al (1999). The final part of Ward-Lonergan & Nicholas’ (1998) programme consists of Functional Drawing Training in which tasks are designed to resemble typical conversational interactions between two people. The subject, Mr G., was requested to communicate information pertaining to recent or previous events that had occurred in his life or to current or historical world events. Initially specific scenarios were provided such as “Draw something about the Kennedy assassination”, but later more open-ended scenarios were presented e.g “Draw something you did at the weekend.” Examples of the drawings produced are provided which clearly demonstrate improved ability to convey complex events via drawing. In addition, by the end of the treatment programme Mr G was showing generalisation of what he had learned in therapy to his home environment. For example, he used drawing to indicate that a neighbour’s car headlight needed repair and to express what he wanted for lunch. Conversation is used throughout the therapy programme described by Sacchett et al (1999), usually alongside more structured tasks. Like the above study, open-ended Interactive drawing in Aphasia questions are used to elicit drawings about recent events in the participants’ lives, past experiences, world events. These drawings would then form the basis for development of the conversation, with both parties being equal participants in the interaction. Generalisation to other environments was specifically targeted in this study. A qualitative structured interview probe, The Pragmatics Profile (Dewart & Summers 1996) was used with the subjects’ main carers before and after therapy to establish usual communicative behaviour in different daily situations. Although the data from these interviews were not subjected to formal analysis, respondents in the post-therapy interviews frequently reported increased use and usefulness of drawing in everyday communication. Examples are given, such as the man who used drawing to indicate to his wife that he wanted the side of his house painted, or the musician who was able, through drawing, to show his wife how to work his recording studio equipment. The true value and creativity of interactive drawing can best be demonstrated by example. The following is the complete version of a conversation, part of which was published in Sacchett et al (1999), which took place between the clinician (CS), FM, who has aphasia and whose verbal output is limited to the word “Aye!”, and FM’s wife AM (Figure 2). In response to the prompt “Tell me what you did at the weekend.”, FM draws portion 1, which demonstrates the importance of shared knowledge and context Although this drawing would be unrecognisable to a naive interpreter in isolation, familiarity with FM’s life and interests and with his drawing style enabled the clinician to quickly deduce that the drawing represented a group of four musicians. The ensuing conversation demonstrates a number of principles and techniques of interactive drawing. Firstly the clinician uses drawing herself alongside speech to ask questions and for clarification. FM uses clarification strategies of enlargement and addition of detail to assist Interactive drawing in Aphasia interpretation. He also makes use of other nonverbal modalities such as gesture for expansion or clarification of his contributions to the conversation. Most importantly, although difficult to demonstrate in the finished product, the feel and flow of a natural conversation is maintained throughout the exchange. FM’s role in the conversation is that of equal partner. He draws not only in response to questions, but also to introduce new elements and to develop themes in the conversation. Most importantly, one gets a feel for FM as a person. Insert Figure 2 here Conclusion and future directions This paper has reviewed the literature on drawing to communicate in aphasia. The particular advantages of drawing over other nonverbal communication modalities were discussed, namely the provision of a fixed, permanent record of an exchange that is amenable to modification or expansion by both communication partners, thus promoting the emergence of a combined picture or message (Lyon 1995b). Differing views of the role of drawing in aphasia, as either a substitute for language or an augmentative tool, have led to different perspectives and priorities in therapies for drawing in aphasia rehabilitation. When drawing is viewed as a substitute for language, therapy focuses on improving the recognisability of the drawings produced by the person with aphasia. In contrast, when drawing is viewed as an augmentative modality, therapy focuses on the interactional aspects of communication, with emphasis on the communication partnership and natural interactive contexts. A review of prior research into interactive Interactive drawing in Aphasia drawing allows us to identify the main principles of interactive drawing which can be summarised as follows: • The quality of the drawings produced is less important than their communicative value. • The focus is on participation in natural, mutually satisfying exchanges (interaction) rather than just “getting the message across” (transaction). • Both participants play an equal role in promoting the success of the exchange. • Drawing is used as part of a multimodal communication approach. • Interactive drawing always takes place within a communicative context, usually conversational. The research described in this paper clearly highlights the benefits of interactive drawing to people whose verbal communication is severely limited by aphasia. Up till now, however, endeavours to develop interactive drawing in aphasia have centred on face-toface, low-tech interactions (i.e. using just pen and paper) and indeed for most everyday purposes this would suffice. However the development of ever-more portable and accessible computerised tools increases the possibilities for multi- and cross-disciplinary research in this area. In particular in the field of remote communication there is a shortage of tools accessible by people with severe aphasia. Due to their limited speech, telephone communication is virtually impossible. Whilst e-mail or fax offer slightly more opportunities, these too are restricted by impaired reading and writing abilities and they do not offer the possibility of “conversation”. The development of a portable computer pad which could support interactive graphic communication would open new doors for people with severe aphasia. Interactive drawing in Aphasia Bearing in mind the above principles of interactive drawing, what functions would such a tool need to support? Firstly one would need to be able to draw freehand directly onto the computer pad. As severe aphasia is frequently accompanied by a right hemiplegia, many people have to use their non-preferred hand for drawing and the pad would need to be large enough to support this. The possibility of storing and retrieving one’s drawings would allow easy referral to earlier conversations thus saving time and effort. In addition other personalised icons could be stored such as maps of the person’s home, people or places frequently visited, together with more symbolic icons such as arrows or question marks. Secondly, since interactive drawing is used a part of a multi-modality approach, any tool to support it must be capable of two things. a) It must allow both partners in the communication exchange to draw onto the same screen, to enable clarification strategies such as enlargement, alteration etc. This “same” screen need not, of course, be in the same physical location, but could be some kind of shared screen facility over distance. b) In order to support remote communication, it must be a multi-media facility allowing the non-aphasic interactant to ask questions verbally to assist clarification. Naturally a very quick and simple way of answering Yes and No would also be required. The suggestions given above give a flavour of the requisites of any “high-tech” tool to support interactive graphics with people with aphasia. The benefits conferred by such a tool in facilitating and developing interactive drawing are undeniable. In addition to increasing individuals’ communicative potential, it enables them to demonstrate their competence, thus contributing to their psychosocial well-being. Interactive drawing in Aphasia Interactive drawing in Aphasia APPENDIX 1 Strategies for facilitating interpretation of drawings by communication partners. (Adapted from Sacchett & Lindsay 1998) 1 Ask “homing in” questions (Yes/No type) about the drawing before trying to guess what it is. 2 Ask your partner to show you the important bits. If you don’t recognise them, ask him/her to draw just those bits again, bigger. 3 Ask your partner for other clues e.g “Show me what you do with it.” “Show me how big it is.” 4 Add to or change your partner’s drawing by drawing something yourself - your “best guess”. 5 Write down key words about the drawing as you find things out. Interactive drawing in Aphasia References AJURIAGUERRA, J. D. & HECAEN, H. (1960). Problemes psychologiques de l’aphasie. In Le Cortex Cerebral: Etude Neuro-Psychopathologique. Paris: Masson. BAUER, A. & KAISER, G. (1995). Drawing on drawings. Aphasiology, 9, 68-78. BENTON, A. (1985). Visuoperceptual, visuospatial and visuoconstructive disorders. In K. HEILMAN & E.VALENSTEIN (Eds) Clinical Neuropsychology, 2nd edn. New York: Oxford University Press. DAVIS, G.A. & WILCOX, M. J. (1981). Incorporating parameters of natural conversation in aphasia treatment. In R. CHAPEY (Ed.) Language Intervention Strategies in Adult Aphasia. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins. DEWART, H. & SUMMERS, S. (1996). Pragmatics profile of Everyday Communication Skills in Adults. London: NFER Nelson. DIPPER, L., BLACK, M. & BRYAN, K. (In press) Thinking for speaking and thinking for listening: The interaction of thought and language in typical and non-fluent comprehension and production. Interactive drawing in Aphasia GAINOTTI, G., SILVERI, M.C., VILLA, G. & CALTAGIRONE, C. (1983). Drawing objects from memory in aphasia. Brain, 106: 613-622. GAINOTTI, G. & TIACCI, C. (1970). Patterns of drawing disability in right and left hemisphere patients. Neuropsychologia, 8, 379-384. GREEN, G. (1982). Assessment and treatment of the adult with severe aphasia: aiming for functional generalization. Australian Journal of Human Communication Disorders, 10, 1123. GOUREVITCH, M. (1967). Un aphasique s’exprime par le dessin. L’Encephale, 56, 52-68. HATFIELD, F.M. & ZANGWILL, O.H. (1974). Ideation in aphasia: the picture-story method. Neuropsychologia, 12, 389-393. KACZSMAREK, B.L.J. (1991) Aphasia in an artist: a disorder of symbolic processing. Aphasiology, 5, 361-372. KAGAN, A. (1995). Revealing the competence of aphasic adults through conversation: a challenge to health professionals. Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation, 2, 15-28. Interactive drawing in Aphasia LORANT, De G. & Van EECKHOUT, P. (1980). Sabadel: L’homme qui ne savait plus parler. Paris: Nouvelles Editions Baudeniere. LYON, J.G. (1995a). Drawing: its value as a communication aid for adults with aphasia. Aphasiology, 9, 33-50. LYON, J.G. (1995b). Communicative drawing: an augmentative mode of interaction. Aphasiology, 9, 84-94. LYON, J.G. & HELM-ESTABROOKS, N. (1987). Drawing: its communicative significance for expressively restricted aphasic adults. Topics in Language Disorders, 8, 61-71. LYON, J.G. & SIMS, E. (1989). Drawing: Its use as a communicative aid with aphasic and normal adults. In T. PRESCOTT, Ed. Clinical Aphasiology Proceedings, Vol. 18. San Diego: College Hill Press. MORGAN, A. & HELM-ESTABROOKS, N. (1987). Back to the drawing board: a treatment program for nonverbal aphasic adults. In R. BROOKSHIRE, Ed. Clinical Aphasiology Proceedings. Minneapolis: BRK Publishers. PACHALSKA, M. (1990). Art therapy in aphasia. In M. PACHALSKA, Ed. Proceedings of the First International Aphasia Rehabilitation Congress. Cracow: AWF Press. Interactive drawing in Aphasia PILLON, B., SIGNORET, J.L., Van EECKHOUT, P. & LHERMITTE, F. (1980). Le dessin chez un aphasique. Incidence possible sur le langage et sa reeducation. Revue Neurologique, 136, 699-710. POUND, C., PARR, S., LINDSAY, J., WOOLF, C. (2000). Beyond Aphasia: Therapies for Living with Com munication Disability. Oxon: Winslow Press. SACCHETT, C., BYNG, S., MARSHALL, J. & POUND, C. (1999). Drawing together: evaluation of a therapy programme for severe aphasia. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 34, 265-289. SACCHETT, C. & LINDSAY, J. (1998). Communicative drawing for severe aphasia: revealing competence and rebuilding identity. Paper presented at the British Aphasiology Society Therapy Symposium, Madingley, Cambridge. SIMMONS-MACKIE, N. (1998) In support of supported conversation for adults with aphasia. Aphasiology, 12, 831-838. SIMMONS-MACKIE, N. & DAMICO, J. (1995). Communicative competence and aphasia: evidence from compensatory strategies. In M. LEMME, Ed. Clinical Aphasiology, Vol 23. Austin: Pro-Ed. Interactive drawing in Aphasia SWINDELL, C.S., HOLLAND, A.L., FROMM, D. & GREENHOUSE, J.B. (1988). Characteristics of recovery of drawing ability in left and right brain-damaged patients. Brain and Cognition, 6, 16-30. TRUPE, E.H. (1986). Training severely aphasic patients to communicate by drawing. Paper presented at the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association Convention, Detroit, MI. WARD-LONERGAN, J.M. & NICHOLAS, M.L. (1998). Drawing to communicate: a case report of an adult with global aphasia. European Journal of Disorders of Communication, 30, 475-91. WARRINGTON, E.K., JAMES, M. & KINSBOURNE, M.(1966). Drawing disability in relation to laterality of cerebral lesion. Brain 89, 53-82. YEDOR, K. & KEARNS, K. (1987). Establishing communicative drawing in severe aphasia through response elaboration training. Paper presented at the American SpeechLanguage-Hearing Association Convention, New Orleans, LA. Interactive drawing in Aphasia Footnotes 1 Figures obtained from Speakability, a UK charity which aims to promote public awareness of aphasia and offers services to people with aphasia 2 Wernicke’s aphasia, sometimes referred to as jargon aphasia, is characterised by fluent ‘empty’ speech, lacking in content whilst maintaining syntactic form. Naming abilities are severely limited and often characterised by the production of neologisms. Auditory and reading comprehension are usually severely impaired. 3 Broca’s aphasia is characterised by non-fluent agrammatic speech, consisting of a string of content words not linked by any syntactic form. Auditory and reading comprehension are relatively spared, although there may be some impairment in these modalities. Interactive drawing in Aphasia Legends to figures FIGURE 1 Drawing produced by GJ following communicative drawing therapy, in which he “tells a story” by depicting a series of complex events. The stick figure holding flowers in panel 1 and the small drawing above panel 2 were drawn by the clinician. The remainder was drawn by GJ with no prompting. FIGURE 2 Example of interactive drawing in conversation between clinician (CS), person with aphasia (FM) and FM’s wife (A). Figures reproduced from Sacchett et al 1999, with the permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd. www.tandf.co.uk Interactive drawing in Aphasia FIGURE 2 Accompanying text 1 CS these are people, right? (draws 4 stick people) FM aye CS then you drew something else on top of them (points to drawing). it’s not very clear. can you draw just 2 that thing? FM (draws guitar) CS so these are guitars. you went to see a band? FM aye, aye! CS this is the drummer (points to detail 1a) FM aye CS these are two guitarists. what about this one (points to 1b) (draws microphone) is he just a singer or does he play an instrument? 3 FM (draws 3a) CS I’m not sure what it is. an amplifier? FM (draws 3b) CS a keyboard? FM aye, aye! Interactive drawing in Aphasia 4 CS where did you see this band? FM (draws 4 and gestures switching on/off) CS is this your mixing desk? FM aye (draws 4a) CS looks like you’re standing on it. FM aye! (mimes singing) CS so you had a good time then! AM that’s not actually [F]. it’s a friend of ours. rather the worse for wear I’m afraid. he was dancing on the table. we did have a good time though, didn’t we [F]? FM aye, aye! (laughs) 5 CS so it’s in a studio. your studio? FM (shakes head) CS a friend’s? FM aye CS so you were helping this friend produce a record? (draws record) FM aye aye! AM draw where the studio was FM (draws 5) CS it looks like a church (draws cross on top) FM (draws over cross) aye aye! CS a converted church. whose studio was it? someone famous? 6 FM (draws 6) Interactive drawing in Aphasia AM he’s drawing the carpet. you can tell from the carpet who owns it. CS well I can’t I’m afraid AM it’s a tartan carpet CS a fellow scot then? FM aye! aye! (laughs) Interactive drawing in Aphasia FIGURE 1 Interactive drawing in Aphasia Figure 2 View publication stats