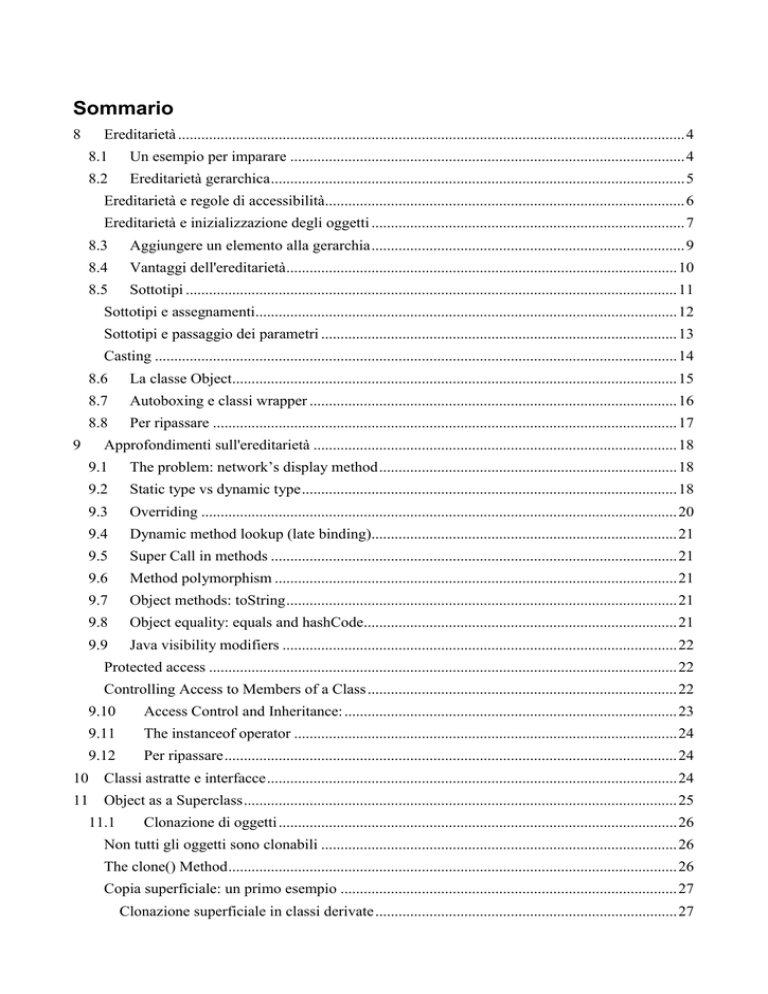

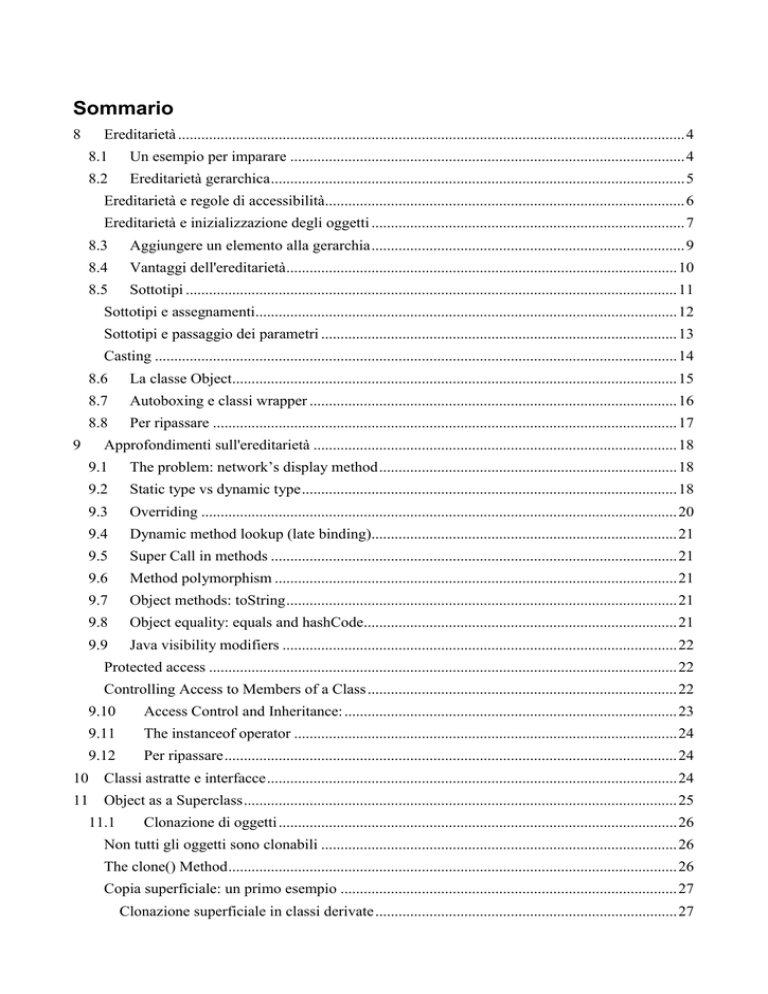

Sommario

8

Ereditarietà ................................................................................................................................... 4

8.1

Un esempio per imparare ...................................................................................................... 4

8.2

Ereditarietà gerarchica ........................................................................................................... 5

Ereditarietà e regole di accessibilità............................................................................................. 6

Ereditarietà e inizializzazione degli oggetti ................................................................................. 7

8.3

Aggiungere un elemento alla gerarchia ................................................................................. 9

8.4

Vantaggi dell'ereditarietà ..................................................................................................... 10

8.5

Sottotipi ............................................................................................................................... 11

Sottotipi e assegnamenti............................................................................................................. 12

Sottotipi e passaggio dei parametri ............................................................................................ 13

Casting ....................................................................................................................................... 14

La classe Object................................................................................................................... 15

8.7

Autoboxing e classi wrapper ............................................................................................... 16

8.8

Per ripassare ........................................................................................................................ 17

9

8.6

Approfondimenti sull'ereditarietà .............................................................................................. 18

9.1

The problem: network’s display method ............................................................................. 18

9.2

Static type vs dynamic type ................................................................................................. 18

9.3

Overriding ........................................................................................................................... 20

9.4

Dynamic method lookup (late binding)............................................................................... 21

9.5

Super Call in methods ......................................................................................................... 21

9.6

Method polymorphism ........................................................................................................ 21

9.7

Object methods: toString ..................................................................................................... 21

9.8

Object equality: equals and hashCode................................................................................. 21

9.9

Java visibility modifiers ...................................................................................................... 22

Protected access ......................................................................................................................... 22

Controlling Access to Members of a Class ................................................................................ 22

9.10

Access Control and Inheritance: ...................................................................................... 23

9.11

The instanceof operator ................................................................................................... 24

9.12

Per ripassare ..................................................................................................................... 24

10

Classi astratte e interfacce .......................................................................................................... 24

11

Object as a Superclass ................................................................................................................ 25

11.1

Clonazione di oggetti ....................................................................................................... 26

Non tutti gli oggetti sono clonabili ............................................................................................ 26

The clone() Method .................................................................................................................... 26

Copia superficiale: un primo esempio ....................................................................................... 27

Clonazione superficiale in classi derivate .............................................................................. 27

Copia superficiale e profonda: differenze .................................................................................. 27

Esempio: Classe Segmento .................................................................................................... 28

Copia superficiale .................................................................................................................. 29

Copia profonda: significato .................................................................................................... 29

Copia profonda: realizzazione ............................................................................................... 30

11.2

Uguaglianza tra oggetti .................................................................................................... 31

Uguaglianza superficiale ............................................................................................................ 31

Uguaglianza profonda ................................................................................................................ 32

11.3

The finalize() Method ...................................................................................................... 32

11.4

The getClass() Method .................................................................................................... 33

11.5

The hashCode() Method .................................................................................................. 33

11.6

The toString() Method ..................................................................................................... 33

11.7

Confronto tra oggetti........................................................................................................ 34

L'interfaccia java.lang.Comparable ......................................................................... 34

Ordinamento di Array con java.util.Arrays.sort() ...................................................................... 37

Ordinamento di List con java.util.Collections ........................................................................... 38

Collections vs Collection ........................................................................................................... 39

Ordinamento mediante l'interfaccia java.util.Comparator ......................................................... 40

11.8

Classi Nested ................................................................................................................... 43

Osservazioni ........................................................................................................................... 43

Convertire un ArrayList in un Array ............................................................................... 48

11.10

Convertire ArrayList in Array ......................................................................................... 49

12

11.9

Interfacce Grafiche (GUI) .......................................................................................................... 49

12.1

Elementi di un'interfaccia grafica .................................................................................... 49

12.2

AWT e Swing .................................................................................................................. 50

12.3

La prima applicazione grafica ......................................................................................... 50

Aggiunta di menu ....................................................................................................................... 51

Gestione degli eventi .................................................................................................................. 52

Osservazione importante: meglio avere listeners distinti per oggetti distinti ........................ 54

Inner classes (rivisitate) ............................................................................................................. 54

Anonymous inner classes ........................................................................................................... 56

12.4

Un programma per la visualizzazione e modifica delle immagini: prima versione ........ 58

12.5

Layouts ............................................................................................................................ 62

BorderLayout ......................................................................................................................... 63

FlowLayout ............................................................................................................................ 63

GridLayout ............................................................................................................................. 64

BoxLayout .............................................................................................................................. 64

Nested Containers ...................................................................................................................... 65

12.6

Creazione di un'interfaccia grafica con NetBeans ........................................................... 66

Esercizio 1: Il “gioco del 15”. .................................................................................................... 67

Versione con numeri .............................................................................................................. 67

Versione con immagini “puzzlefy” ........................................................................................ 67

Esercizio 2: Emulare la calcolatrice standard di Windows ........................................................ 67

13

Gestione delle eccezioni (rivisitate) ........................................................................................... 69

Approfondimenti.............................................................................................................. 69

13.2

Logging delle eccezioni e di situazioni specifiche: java.util.logging package ................ 69

14

13.1

Gestione dei file in Java ............................................................................................................. 69

java.io.File ....................................................................................................................... 69

14.2

java.util.Formatter e java.util.Scanner; ............................................................................ 70

14.3

Scrivere su file di testo con PrintWriter e BufferedWriter una riga alla volta ................ 73

14.4

Leggere da file di testo una riga alla volta con BufferedReader ..................................... 74

14.5

Un esempio di lettura da file CSV ................................................................................... 74

14.6

Un esempio di scrittura su file CSV ................................................................................ 75

14.7

Un esempio di uso di PrintWriter e BufferedReader ....................................................... 76

14.8

Serializzazione di oggetti ................................................................................................. 77

14.9

Progetto di una rubrica di contatti ................................................................................... 78

15

14.1

Riferimenti per Java ................................................................................................................... 78

In queste note si seguirà l'approccio del testo Objects First with Java i cui esempi (utilizzati in queste

note) sono liberamente scaricabili al link http://www.bluej.org/objects-first/resources/projects.zip .

8 Ereditarietà

8.1 Un esempio per imparare

Apriamo il progetto network-v1: esploriamo il codice e poi proviamo a creare alcuni oggetti.

Esercizio: discutere il codice e trovare eventuali problemi di progettazione.

Il problema fondamentale è che le classi MessagePost e PhotoPost condividono molto codice comune.

E se la nostra applicazione chiedesse di fare anche un ActivityPost (qualcosa che ci aggiorna sui

nostri contatti...qualcosa del tipo “tizio è ora amico di...”

Per risolvere il problema della duplicazione del codice possiamo utilizzare il concetto di ereditarietà:

creiamo una classe Post che contiene gli attributi e i metodi comuni di tutti i post e poi deriviamo il

MessagePost e il PhotoPost come classi che estendono la classe Post.

“The purpose of using inheritance is now fairly obvious. Instances of class MessagePost will have

all fields defined in class MessagePost and in class Post. (MessagePost inherits the fields from

Post.) Instances of PhotoPost will have all fields defined in PhotoPost and in Post. Thus, we

achieve the same as before, but we need to define the fields username, timestamp, likes, and

comments only once, while being able to use them in two different places).

The same holds true for methods: instances of subclasses have all methods defined in both the

superclass and the subclass. In general, we can say: because a message post is a post, a message-post

object has everything that a post has, and more. And because a photo post is also a post, it has

everything that a post has, and more. Thus, inheritance allows us to create two classes that are quite

similar, while avoiding the need to write the identical part twice. Inheritance has a number of other

advantages, which we discuss below. First, however, we will take another, more general look at

inheritance hierarchies.

”

8.2 Ereditarietà gerarchica

The principle is simple: inheritance is an abstraction technique that lets us categorize classes of

objects under certain criteria and helps us specify the characteristics of these classes.

public class Post

{

private String username; // username of the post’s author

private long timestamp;

private int likes;

private ArrayList<String> comments;

}

// Constructors and methods omitted.

public class MessagePost extends Post

{

private String message;

}

// Constructors and methods omitted.

public class PhotoPost extends Post

{

private String filename;

private String caption;

}

// Constructors and methods omitted.

Ereditarietà e regole di accessibilità

Members defined as public in either the superclass or subclass portions will be accessible to objects

of other classes, but members defined as private will be inaccessible. In fact, the rule on privacy

also applies between a subclass and its superclass: a subclass cannot access private members of its

superclass. It follows that if a subclass method needed to access or change private fields in its

superclass, then the superclass would need to provide appropriate accessor and/or mutator methods.

However, an object of a subclass may call any public methods defined in its superclass as if they were

defined locally in the subclass—no variable is needed, because the methods are all part of the same

object.

Ereditarietà e inizializzazione degli oggetti

public class Post

{

private String username; // username of the post’s author

private

long timestamp;

private int likes;

private ArrayList<String> comments;

/**

* Constructor for objects of class Post.

*

* @param author

The username of the author of this post.

*/

}

public

Post(String author)

{

}

username = author;

timestamp = System.currentTimeMillis();

likes = 0;

comments = new ArrayList<String>();

// Methods omitted.

public class MessagePost extends Post

{

private String message; // an arbitrarily long, multi-line message

/**

* Constructor for objects of class MessagePost.

*

* @param author

* @param text

*/

The username of the author of this post.

The text of this post.

}

public

MessagePost(String author, String text)

{

super(author);

message = text;

}

// Methods omitted.

First, the class Post has a constructor, even though we do not intend to create an instance of class

Post directly.

This constructor receives the parameters needed to initialize the Post fields, and it contains the code

to do this initialization.

Second, the MessagePost constructor receives parameters needed to initialize both Post and

MessagePost fields. It then contains the following line of code:

super(author);

The keyword super is a call from the subclass constructor to the constructor of the superclass. Its

effect is that the Post constructor is executed as part of the MessagePost constructor’s execution.

When we create a message post, the MessagePost constructor is called, which, in turn, as its first

statement, calls the Post constructor. The Post constructor initializes the post’s fields, and then

returns to the MessagePost constructor, which initializes the remaining field defined in the

MessagePost class. For this to work, those parameters needed for the initialization of the post fields

are passed on to the superclass constructor as parameters to the super call.

In Java, a subclass constructor must always call the superclass constructor as its first statement. If

you do not write a call to a superclass constructor, the Java compiler will insert a superclass call

automatically, to ensure that the superclass fields get properly initialized. The inserted call is

equivalent to writing

super();

Inserting this call automatically works only if the superclass has a constructor without parameters

(because the compiler cannot guess what parameter values should be passed). Otherwise, an error

will be reported. In general, it is a good idea to always include explicit superclass calls in your

constructors, even if it is one that the compiler could generate automatically. We consider this good

style, because it avoids the possibility of misinterpretation and confusion in case a reader is not aware

of the automatic code generation.

8.3 Aggiungere un elemento alla gerarchia

Aggiungere la classe EventPost con il campo eventType di tipo enumerativo.

E se volessimo i commenti solo per i messaggi e le foto, ma non per gli eventi:

Il progetto BlueJ con le modifiche dell'esercizio 8.8 diventa network-v2-modified:

8.4 Vantaggi dell'ereditarietà

Avoiding code duplication The use of inheritance avoids the need to write identical or very similar

copies of code twice (or even more often).

Code reuse Existing code can be reused. If a class similar to the one we need already exists, we can

sometimes subclass the existing class and reuse some of the existing code rather than having to

implement everything again.

Easier maintenance Maintaining the application becomes easier, because the relationship between

the classes is clearly expressed. A change to a field or a method that is shared between different types

of subclasses needs to be made only once.

Extendibility Using inheritance, it becomes much easier to extend an existing application in certain

ways.

8.5 Sottotipi

Confrontiamo la classe NewsFeed del progetto network-v2 con la classe NewsFeed del progetto

network-v1. Nella versione con ereditarietà il codice è molto più semplice perché abbiamo solo il tipo

Post e possiamo scrivere metodi che aggiungono un post oppure mostrano il contenuto di un post,

senza specificare se si tratta di MessagePost o di PhotoPost.

public void addPost(Post post)

{

posts.add(post);

}

/**

* Show the news feed. Currently: print the news feed details

* to the terminal. (To do: replace this later with display

* in web browser.)

*/

public void show()

{

// display all posts

for(Post post : posts) {

post.display();

System.out.println();

// empty line between posts

}

}

In our first version, we had two methods to add posts to the news feed. They had the following headers:

public void addMessagePost(MessagePost message)

public void addPhotoPost(PhotoPost photo)

In our new version, we have a single method to serve the same purpose:

public void addPost(Post post)

So far, we have interpreted the requirement that parameter types must match as meaning “must be of

the same type”—for instance, that the type name of an actual parameter must be the same as the type

name of the corresponding formal parameter.

This is only part of the truth, in fact, because an object of a subclass can be used wherever its

superclass type is required.

Sottotipi e assegnamenti

Imagine that we have a class Vehicle with two subclasses, Car and Bicycle (Figure 8.9). In this case, the typing rule

admits that the following assignments are all legal:

Vehicle v1 = new Vehicle();

Vehicle v2 = new Car();

Vehicle v3 = new Bicycle();

Because a car is a vehicle, it is perfectly legal to store a car in a variable that is intended for

vehicles

This principle is known as substitution. In object-oriented languages, we can

substitute a subclass object where a superclass object is expected, because the

subclass object is a special case of the superclass. If, for example, someone asks us to give

them a pen, we can fulfill the request perfectly well by giving them a fountain pen or a ballpoint pen.

Both fountain pen and ballpoint pen are subclasses of pen, so supplying either where an object of

class

However, doing it the other way is not allowed:

Car c1 = new Vehicle(); // this is an error!

This statement attempts to store a Vehicle object in a Car and an error will be reported if you try to

compile this statement. A vehicle, on the other hand, may or may not be a car—we do not know.

Thus, the statement may be wrong and is not allowed.

Similarly:

Car c2 = new Bicycle(); // this is an error!

This is also an illegal statement. A bicycle is not a car

Sottotipi e passaggio dei parametri

public class NewsFeed

{

public void addPost(Post post)

{

. . .

}

}

We can now use this method to add message posts and photo posts to the feed:

NewsFeed feed = new NewsFeed();

MessagePost message = new MessagePost()

PhotoPost photo = new PhotoPost(...);

feed.addPost(message);

feed.addPost(photo);

Because of subtyping rules, we need only one method (with a parameter of type both MessagePost

and PhotoPost objects.

Casting

Sometimes the rule that we cannot assign from a supertype to a subtype is more restrictive than

necessary. If we know that the supertype variable holds a subtype object, the assignment could

actually be allowed. For example:

Vehicle v;

Car c = new Car();

v = c; // correct

c = v; // error

The above statements would not compile: we get a compiler error in the last line, because assigning

a Vehicle variable to a Car variable (supertype to subtype) is not allowed. However, if we execute

these statements in sequence, we know that we could actually allow this assignment. We can see that

the variable v actually contains an object of type Car, so the assignment to c would be okay. The

compiler is not that smart. It translates the code line by line, so it looks at the last line in isolation

without knowing what is currently stored in variable v. This is called type loss. The type of the object

in v is actually Car, but the compiler does not know this.

We can get around this problem by explicitly telling the type system that the variable v holds a Car

object. We do this using a cast operator:

c = (Car) v; // okay

The cast operator consists of the name of a type (here, Car) written in parentheses in front of a variable

or an expression. Doing this will cause the compiler to believe that the object is a Car, and it will not

report an error.

At runtime, however, the Java system will check that it really is a Car. If we were careful, and it is

truly is a Car, everything is fine. If the object in v is of another type, the runtime system will indicate

an error (called a ClassCastException), and the program will stop.

Now consider this code fragment, in which Bicycle is also a subclass of Vehicle:

Vehicle v;

Car c;

Bicycle b;

c = new Car();

v = c; // okay

b = (Bicycle) c; // compile time error!

b = (Bicycle) v; // runtime error!

The last two assignments will both fail. The attempt to assign c to b (even with the cast) will be a

compile-time error. The compiler notices that Car and Bicycle do not form a subtype/supertype

relationship, so c can never hold a Bicycle object—the assignment could never work. The attempt

to assign v to b (with the cast) will be accepted at compile time but will fail at runtime. Vehicle is a

superclass of Bicycle, and thus v can potentially hold a Bicycle object.

At runtime, however, it turns out that the object in v is not a Bicycle but a Car, and the program will

terminate prematurely.

Casting should be avoided wherever possible, because it can lead to runtime errors, and that is

clearly something we do not want. The compiler cannot help us to ensure correctness in this case. In

practice, casting is very rarely needed in a well-structured object-oriented program. In almost all

cases, when you use a cast in your code, you could restructure your code to avoid this cast and

end up with a better-designed program. This usually involves replacing the cast with a

polymorphic method call (more about this in the next chapter).

8.6 La classe Object

All classes have a superclass. So far, it has appeared as if most classes we have seen do not have a

superclass. In fact, while we can declare an explicit superclass for a class, all classes that have no

superclass declaration implicitly inherit from a class called Object.

Object is a class from the Java standard library that serves as a superclass for all objects.

Writing a class declaration such as

public class Person

{

...

}

is equivalent to writing

public class Person extends Object

{

...

}

The Java compiler automatically inserts the Object superclass for all classes without an explicit

extends declaration, so it is never necessary to do this for yourself. Every single class (with the sole

exception of the Object class itself) inherits from Object, either directly or indirectly.

The following figure shows some randomly chosen classes to illustrate this.

8.7 Autoboxing e classi wrapper

We have seen that, with suitable parameterization, the collection classes can store objects of any

object type. There remains one problem: Java has some types that are not object types. As we know,

the simple types—such as int, boolean, and char—are separate from object types. Their values are

not instances of classes, and they do not inherit from the Object class.

Because of this, they are not subtypes of Object, and it would not normally be possible to add them

into a collection.

This is unfortunate. There are situations in which we might want to create a list of int values or a set

of char values, for instance. What can we do? Java’s solution to this problem is wrapper classes.

Every primitive type in Java has a corresponding wrapper class that represents the same type but is a

real object type. The wrapper class for int, for example, is called Integer.

The following statement explicitly wraps the value of the primitive int variable ix in an Integer

object:

Integer iwrap = new Integer(ix);

And now iwrap could obviously easily be stored in an ArrayList<Integer> collection, for instance.

However, storing of primitive values into an object collection is made even easier through a compiler

feature known as autoboxing.

Whenever a value of a primitive type is used in a context that requires a wrapper type, the compiler

automatically wraps the primitive-type value in an appropriate wrapper object. This means that

primitive-type values can be added directly to a collection:

private ArrayList<Integer> markList;

...

public void storeMarkInList(int mark)

{

markList.add(mark);

}

The reverse operation—unboxing—is also performed automatically, so retrieval from a collection

might look like this:

int firstMark = markList.remove(0);

Autoboxing is also applied whenever a primitive-type value is passed as a parameter to a method that

expects a wrapper type and when a primitive-type value is stored in a wrapper-type variable. Similarly,

unboxing is applied when a wrapper-type value is passed as a parameter to a method that expects a

primitive-type value and when stored in a primitive-type variable.

It is worth noting that this almost makes it appear as if primitive types can be stored in collections.

However, the type of the collection must still be declared using the wrapper type (e.g.,

ArrayList<Integer>, not ArrayList<int>).

Esercizio:

8.8 Per ripassare

9 Approfondimenti sull'ereditarietà

9.1 The problem: network’s display method

Vedere il libro

9.2 Static type vs dynamic type

Prendiamo il progetto network-v2 e osserviamo il comportamento del metodo display

Cosa succede se Post non ha il metodo display e nella classe NewsFeed si richiama il metodo

/**

* Show the news feed. Currently: print the news feed details

* to the terminal. (To do: replace this later with display

* in web browser.)

*/

public void show()

{

// display all posts

for(Post post : posts) {

post.display();

System.out.println();

// empty line between posts

}

}

Quale metodo display è invocato nel ciclo for-each?

We know that every Post object in the collection is in fact a MessagePost or a PhotoPost object,

and both have display methods. This should mean that post.display() ought to work, because,

whatever it is— MessagePost or PhotoPost—we know that it does have a display method.

Consider the following statement:

Vehicle v1 = new Car();

What is the type of v1? That depends on what precisely we mean by “type of v1.” The type of the

variable v1 is Vehicle; the type of the object stored in v1 is Car. Through subtyping and substitution

rules, we now have situations where the type of the variable and the type of the object stored in it are

not exactly the same.

Let us introduce some terminology to make it easier to talk about this issue:

We call the declared type of the variable the static type, because it is declared in the source code—

the static representation of the program.

We call the type of the object stored in a variable the dynamic type, because it depends on assignments

at runtime—the dynamic behavior of the program.

Thus, looking at the explanations above, we can be more precise: the static type of v1 is Vehicle, the

dynamic type of v1 is Car. We can now also rephrase our discussion about the call to the post’s

display method in the NewsFeed class. At the time of the call

post.display();

the static type of post is Post, while the dynamic type is either MessagePost or PhotoPost. We

do not know which one of these it is, assuming that we have entered both

MessagePost and PhotoPost objects into the feed.

9.3 Overriding

Il progetto network-v3 fornisce un'implementazione delle classi secondo quanto descritto

nell'esercizio 9.2

The technique we are using here is called overriding (sometimes it is also referred to as redefinition).

Overriding is a situation where a method is defined in a superclass (method display in class Post in

this example), and a method with exactly the same signature is defined in the subclass.

In this situation, objects of the subclass have two methods with the same name and header: one

inherited from the superclass and one from the subclass. Which one will be executed when we call

this method?

9.4 Dynamic method lookup (late binding)

Vedere §9.4 del libro.

9.5 Super Call in methods

Vedere §9.5 del libro.

9.6 Method polymorphism

Vedere §9.6 del libro.

9.7 Object methods: toString

Vedere §9.7 del libro.

9.8 Object equality: equals and hashCode

Esercizio: Creare due oggetti

Track t1 = new Track(“artista”, “titolo canzone 1”, “file name 1”);

Track t2 = new Track(“artista”, “titolo canzone 1”, “file name 1”);

e verificare se il metodo equals restituisce vero o falso.

t1.equals(t2)

Ridefinire il metodo equals() nella classe Track in modo che verifichi se i campi (variabili

d'istanza) siano a loro volta uguali.

t1.equals(t2)

Richiamare il metodo hashCode sugli oggetti t1 e t2 e commentare il risultato ottenuto.

t1.hashCode()

Eseguire le istruzioni

System.out.println(t1);

System.out.println(t2);

commentare il risultato

Ridefinire il metodo toString della classe Track in modo che presenti una descrizione completa

di una traccia e rieseguire le istruzioni:

System.out.println(t1);

System.out.println(t2);

9.9 Java visibility modifiers

http://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/java/javaOO/accesscontrol.html

http://www.tutorialspoint.com/java/java_access_modifiers.htm

Protected access

Vedere §9.9 del libro.

Controlling Access to Members of a Class

Access level modifiers determine whether other classes can use a particular field or invoke a

particular method. There are two levels of access control:

At the top level—public, or package-private (no explicit modifier).

At the member level—public, private, protected, or package-private (no explicit

modifier).

A class may be declared with the modifier public, in which case that class is visible to all classes

everywhere. If a class has no modifier (the default, also known as package-private), it is visible

only within its own package (packages are named groups of related classes — you will learn

about them in a later lesson.)

At the member level, you can also use the public modifier or no modifier (package-private) just

as with top-level classes, and with the same meaning. For members, there are two additional

access modifiers: private and protected. The private modifier specifies that the member can only

be accessed in its own class. The protected modifier specifies that the member can only be

accessed within its own package (as with package-private) and, in addition, by a subclass of its

class in another package.

The following table shows the access to members permitted by each modifier.

Access Levels

Modifier

Class Package Subclass World

public

Y

Y

Y

Y

protected Y

Y

Y

N

no modifier Y

Y

N

N

private

Y

N

N

N

The first data column indicates whether the class itself has access to the member defined by the

access level. As you can see, a class always has access to its own members. The second column

indicates whether classes in the same package as the class (regardless of their parentage) have

access to the member. The third column indicates whether subclasses of the class declared outside

this package have access to the member. The fourth column indicates whether all classes have

access to the member.

Access levels affect you in two ways. First, when you use classes that come from another source,

such as the classes in the Java platform, access levels determine which members of those classes

your own classes can use. Second, when you write a class, you need to decide what access level

every member variable and every method in your class should have.

Let's look at a collection of classes and see how access levels affect visibility. The following

figure shows the four classes in this example and how they are related.

Classes and Packages of the Example Used to Illustrate Access

Levels

The following table shows where the members of the Alpha class are visible for each of the access

modifiers that can be applied to them.

Visibility

Modifier

public

protected

no modifier

private

Alpha

Y

Y

Y

Y

Beta

Y

Y

Y

N

Alphasub

Y

Y

N

N

Gamma

Y

N

N

N

Tips on Choosing an Access Level:

If other programmers use your class, you want to ensure that errors from misuse cannot

happen. Access levels can help you do this.

Use the most restrictive access level that makes sense for a particular member.

Use private unless you have a good reason not to.

Avoid public fields except for constants. (Many of the examples in the tutorial

use public fields. This may help to illustrate some points concisely, but is not

recommended for production code.) Public fields tend to link you to a particular

implementation and limit your flexibility in changing your code.

9.10 Access Control and Inheritance:

http://www.tutorialspoint.com/java/java_access_modifiers.htm

The following rules for inherited methods are enforced:

Methods declared public in a superclass also must be public in all subclasses.

Methods declared protected in a superclass must either be protected or public in

subclasses; they cannot be private.

Methods declared without access control (no modifier was used) can be declared more

private in subclasses.

Methods declared private are not inherited at all, so there is no rule for them.

9.11 The instanceof operator

Vedere §9.10 del libro

Con riferimento al progetto network-v2 estendere la classe NewsFeed introducendo la classe

ElaboratedNewsFeed che introduce il metodo showMessage che stampa solo i MessagePost e

showPhoto che stampa solo i PhotoPost.

9.12 Per ripassare

10 Classi astratte e interfacce

1. Vedere le slide su classi astratte e interfacce

2. Vedere gli esempi tratti da “Java How to Program”

3. Svolgere il seguente esercizio:

Esercizio:

In riferimento al diagramma UML allegato costruire la seguente gerarchia di classi secondo la

descrizione seguente:

La prima classe descrive un lavoratore generico (Lavoratore). Nello specifico il lavoratore

possiede la proprietà matricola, la proprietà cognome, la proprietà nome Inoltre, un lavoratore

per essere tale deve implementare un metodo per il calcolo dello stipendio mensile.

La seconda classe descrive un lavoratore a progetto (Contrattista). Nello specifico il

lavoratore a progetto è un lavoratore, per cui possiede tutte le caratteristiche della classe

Lavoratore e possiede la proprietà oreMensili, che indica il numero di ore lavorate e la

proprietà euroOra, che indica la tariffa oraria del lavoratore a progetto. Inoltre, come richiesto

dalla superclasse Lavoratore, la classe Contrattista implementa il metodo per il calcolo dello

stipendio.

La

terza

classe

descrive

un

lavoratore

a

tempo

indererminato

(LavoratoreTempoIndeterminato).Nello specifico lavoratore a tempo indeterminato è un

lavoratore, per cui possiede tutte le caratteristiche della classe Lavoratore e possiede la

proprietà mensilita, che indica il numero di mensilità del lavoratore a tempo indeterminato,e

la proprietà lordoAnnuo, che indica la cifra annua che il lavoratore a tempo indeterminato

riceve.

Inoltre,come

richiesto

dalla

superclasse

Lavoratore,

la

classe

LavoratoreTempoIndeterminato implementa il metodo per il calcolo dello stipendio.

La quarta classe descrive un direttore che si occupa dei pagamenti dei propri

lavoratori(Direttore). Un direttore è un lavoratore a tempo indeterminato che in più percepisce

un bonus mensile per il raggiungimento degli obiettivi aziendali. Dipendentemente dal tipo di

lavoratore, il direttore calcola lo stipendio

11 Object as a Superclass

Tratto da https://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/java/IandI/objectclass.html

The Object class, in the java.lang package, sits at the top of the class hierarchy tree. Every class is a

descendant, direct or indirect, of the Object class. Every class you use or write inherits the instance methods

of Object. You need not use any of these methods, but, if you choose to do so, you may need to override them

with code that is specific to your class. The methods inherited from Object that are discussed in this section are:

protected Object clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException

Creates and returns a copy of this object.

public boolean equals(Object obj)

Indicates whether some other object is "equal to" this one.

protected void finalize() throws Throwable

Called by the garbage collector on an object when garbage

collection determines that there are no more references to the object

public final Class getClass()

Returns the runtime class of an object.

public int hashCode()

Returns a hash code value for the object.

public String toString()

Returns a string representation of the object.

11.1 Clonazione di oggetti

Clonare un oggetto vuol dire creare una “copia” di un oggetto

http://www.dis.uniroma1.it/~liberato/laboratorio/clone/clone.html

Non tutti gli oggetti sono clonabili

Non tutti gli oggetti sono clonabili:

String a, b;

a=new String("abcd");

b=(String) a.clone(); // errore

Le stringhe non si clonano in quanto sono oggetti immutabili. Per creare una stringa che sia la copia di

un'altra basta usare il copy constructor:

a=new String("abcd");

b=String(a); // crea una nuova istanza della stringa con gli stessi

caratteri di a

Per le stringhe si può fare la copia in modo più efficiente sfruttando il fatto che si tratta di oggetti immutabili:

a=new String("abcd");

String b = a;

In questo caso non c'è nessun problema a fare la copia passando il riferimento allo stesso oggetto dal momento

che una volta creata una stringa non può più essere modificata.

The clone() Method

If a class, or one of its superclasses, implements the Cloneable interface, you can use the clone() method to

create a copy from an existing object. To create a clone, you write:

aCloneableObject.clone();

Object's implementation of this method checks to see whether the object on which clone() was invoked

implements

the Cloneable interface.

If

the

object

does

not,

the

method

throws

a CloneNotSupportedException exception. Exception handling will be covered in a later lesson. For the

moment, you need to know that clone() must be declared as

protected Object clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException

or:

public Object clone() throws CloneNotSupportedException

if you are going to write a clone() method to override the one in Object.

If the object on which clone() was invoked does implement the Cloneable interface, Object's implementation

of the clone() method creates an object of the same class as the original object and initializes the new object's

member variables to have the same values as the original object's corresponding member variables.

The simplest way to make your class cloneable is to add implements Cloneable to your class's declaration.

Then your objects can invoke the clone() method.

For some classes, the default behavior of Object's clone() method works just fine. If, however, an object

contains a reference to an external object, say ObjExternal , you may need to override clone() to get correct

behavior. Otherwise, a change in ObjExternal made by one object will be visible in its clone also. This means

that the original object and its clone are not independent—to decouple them, you must override clone() so that it

clones the object and ObjExternal. Then the original object references ObjExternal and the clone references

a clone of ObjExternal, so that the object and its clone are truly independent.

Copia superficiale: un primo esempio

Clonazione usando clone di Object

class Studente implements Cloneable {

...

public Object clone() {

try {

return super.clone();

}

catch(CloneNotSupportedException e) {

return null;

}

}

}

la classe deve implementare Cloneable

dato che clone di Object ha throws CloneNotSupportedException, va catturata

Clonazione superficiale in classi derivate

Se Borsista estende Studente:

class Borsista extends Studente {

...

public Object clone() {

return super.clone();

}

}

Commenti:

Non serve implements Cloneable dato che Studente implementa l'interfaccia

Cloneable, anche Borsista la implementa automaticamente in modo indiretto

Non serve catturare l'eccezione, poiché viene già fatto nel clone di Studente

Chi clona l'oggetto?

Quando si invoca clone di Borsista: viene invocato clone di Studente che invoca clone di

Object

È sempre clone di Object che fa la copia!

Copia superficiale e profonda: differenze

Se un oggetto contiene altri riferimenti a oggetti:

Copia superficiale: viene copiato solo l'oggetto

Copia profonda: viene copiato l'oggetto e tutti quelli collegati

Esempio: Classe Segmento

class Segmento {

Point i, f;

}

Clonazione superficiale:

Gli oggetti Point sono esattamente gli stessi.

Clonazione profonda:

Gli oggetti Point non sono gli stessi, ma hanno gli stessi valori dentro

Prima della copia:

Dopo la copia superficiale:

Copia superficiale

Clone di Object fa la copia del solo oggetto

class Segmento implements Cloneable {

Point i, f;

public Object clone() {

try {

return super.clone();

}

catch(CloneNotSupportedException e) {

return null;

}

}

}

Copia profonda: significato

Ha senso richiedere una copia anche dei due oggetti Point

Questo non viene fatto da clone di Object, ma va fatto manualmente:

Copia profonda: realizzazione

Occorre invocare clone su ognuno degli oggetti di cui voglio fare la copia

Notare che super.clone() ha tipo di ritorno Object

Per poter accedere alle componenti, devo fare il cast

Lo stesso vale per le componenti

class Segmento implements Cloneable{

Point i, f;

public Object clone() {

try {

Segmento s;

s=(Segmento) super.clone();

s.i=(Point) this.i.clone();

s.f=(Point) this.f.clone();

return s;

}

catch(CloneNotSupportedException e) {

return null;

}

}

}

Osservazioni:

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/lang/Cloneable.html

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/lang/Object.html#clone--

11.2 Uguaglianza tra oggetti

The equals() Method

The equals()

method compares two objects for equality and returns true

if they are equal. The

equals()method provided in the Object class uses the identity operator (==) to determine whether two objects

are equal. For primitive data types, this gives the correct result. For objects, however, it does not.

The equals() method provided by Object tests whether the object references are equal—that is, if the objects

compared are the exact same object.

To test whether two objects are equal in the sense of equivalency (containing the same information), you must

override the equals() method. Here is an example of a Book class that overrides equals():

public class Book {

...

public boolean equals(Object obj) {

if (obj instanceof Book)

return ISBN.equals((Book)obj.getISBN());

else

return false;

}

}

Consider this code that tests two instances of the Book class for equality:

// Swing Tutorial, 2nd edition

Book firstBook = new Book("0201914670");

Book secondBook = new Book("0201914670");

if (firstBook.equals(secondBook)) {

System.out.println("objects are equal");

} else {

System.out.println("objects are not equal");

}

This program displays objects are equal even though firstBook and secondBook reference two distinct

objects. They are considered equal because the objects compared contain the same ISBN number.

You should always override the equals() method if the identity operator is not appropriate for your class.

Note: If you override equals() , you must override hashCode() as well.

Uguaglianza superficiale

Si confrontano i riferimenti degli oggetti

Due oggetti Segmento sono “equals” se i loro campi sono esattamente uguali

(contengono riferimenti agli stessi identici oggetti)

class Segmento {

Point i, f;

// equals superficiale

public boolean equals(Object o) {

if(o==null)

return false;

if(this.getClass()!=o.getClass())

return false;

Segmento s=(Segmento) o;

return((this.i==s.i)&&(this.f==s.f));

}

}

Uguaglianza profonda

Gli oggetti vengono confrontati in base ai loro valori, non ai loro riferimenti:

class Segmento {

Point i, f;

public boolean equals(Object o) {

if(o==null)

return false;

if(this.getClass()!=o.getClass())

return false;

Segmento s=(Segmento) o;

if(this.i==null) {

if(s.i!=null)

return false;

}

else if(!this.i.equals(s.i))

return false;

if(this.f==null) {

if(s.f!=null)

return false;

}

else if(!this.f.equals(s.f))

return false;

return true;

}

}

11.3 The finalize() Method

The Object class provides a callback method, finalize(), that may be invoked on an object when it becomes

garbage. Object's implementation of finalize() does nothing—you can override finalize() to do cleanup,

such as freeing resources.

The finalize() method may be called automatically by the system, but when it is called, or even if it is called, is

uncertain. Therefore, you should not rely on this method to do your cleanup for you. For example, if you don't close

file descriptors in your code after performing I/O and you expect finalize() to close them for you, you may run

out of file descriptors.

11.4 The getClass() Method

You cannot override getClass .

The getClass() method returns a Class object, which has methods you can use to get information about the

class, such as its name (getSimpleName() ), its superclass (getSuperclass()), and the interfaces it

implements (getInterfaces() ). For example, the following method gets and displays the class name of an

object:

void printClassName(Object obj) {

System.out.println("The object's" + " class is " +

obj.getClass().getSimpleName());

}

11.5 The hashCode() Method

The value returned by hashCode() is the object's hash code, which is the object's memory address in

hexadecimal.

By definition, if two objects are equal, their hash code must also be equal. If you override the equals() method,

you change the way two objects are equated and Object 's implementation of hashCode() is no longer valid.

Therefore, if you override the equals() method, you must also override the hashCode() method as well.

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/lang/Object.html#hashCode-http://tutorials.jenkov.com/java-collections/hashcode-equals.html

http://stackoverflow.com/questions/27581/what-issues-should-be-considered-when-overriding-equals-andhashcode-in-java

11.6 The toString() Method

You should always consider overriding the toString() method in your classes.

The Object's toString() method returns a String representation of the object, which is very useful for

debugging. The String representation for an object depends entirely on the object, which is why you need to

override toString() in your classes.

You can use toString() along with System.out.println() to display a text representation of an object,

such as an instance of Book:

System.out.println(firstBook.toString());

which would, for a properly overridden toString() method, print something useful, like this:

ISBN: 0201914670; The Swing Tutorial; A Guide to Constructing GUIs, 2nd Edition

11.7 Confronto tra oggetti

http://www.mkyong.com/java/java-object-sorting-example-comparable-and-comparator/

http://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/collections/interfaces/order.html

Un approccio graduale...con l'uso delle interfacce

java.lang.Comparable https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/lang/Comparable.html per

confrontare oggetti in base a una proprietà

java.util.Comparator https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/util/Comparator.html per

confrontare oggetti in base a un operatore (si usa quando si vuole confrontare gli oggetti sulla base

di più proprietà)

L'interfaccia java.lang.Comparable

Supponiamo di avere la seguente classe:

public class Fruit{

private String fruitName;

private String fruitDesc;

private int quantity;

public Fruit(String fruitName, String fruitDesc, int quantity) {

super();

this.fruitName = fruitName;

this.fruitDesc = fruitDesc;

this.quantity = quantity;

}

public String getFruitName() {

return fruitName;

}

public void setFruitName(String fruitName) {

this.fruitName = fruitName;

}

public String getFruitDesc() {

return fruitDesc;

}

public void setFruitDesc(String fruitDesc) {

this.fruitDesc = fruitDesc;

}

public int getQuantity() {

return quantity;

}

public void setQuantity(int quantity) {

this.quantity = quantity;

}

}

Supponiamo di voler ordinare una collection di oggetti di tipo Fruit in base a una proprietà da

noi scelta, ad esempio la quantità. Come facciamo?

Occorre implementare l'interfaccia java.lang.Comparable e fare overriding del metodo

compareTo() come descritto nel seguente esempio:

public class Fruit implements Comparable<Fruit>{

private String fruitName;

private String fruitDesc;

private int quantity;

public Fruit(String fruitName, String fruitDesc, int quantity) {

super();

this.fruitName = fruitName;

this.fruitDesc = fruitDesc;

this.quantity = quantity;

}

public String getFruitName() {

return fruitName;

}

public void setFruitName(String fruitName) {

this.fruitName = fruitName;

}

public String getFruitDesc() {

return fruitDesc;

}

public void setFruitDesc(String fruitDesc) {

this.fruitDesc = fruitDesc;

}

public int getQuantity() {

return quantity;

}

public void setQuantity(int quantity) {

this.quantity = quantity;

}

@Override

public int compareTo(Fruit compareFruit) {

int compareQuantity = compareFruit.getQuantity();

//ascending order

return this.quantity - compareQuantity;

//descending order

//return compareQuantity - this.quantity;

}

}

Possiamo ora eseguire il seguente codice di esempio:

import java.util.Arrays;

public class SortFruitObject{

public static void main(String args[]){

Fruit[] fruits = new Fruit[4];

Fruit pineappale = new Fruit("Pineapple", "Pineapple description",70);

Fruit apple = new Fruit("Apple", "Apple description",100);

Fruit orange = new Fruit("Orange", "Orange description",80);

Fruit banana = new Fruit("Banana", "Banana description",90);

fruits[0]=pineappale;

fruits[1]=apple;

fruits[2]=orange;

fruits[3]=banana;

Arrays.sort(fruits);

int i=0;

for(Fruit temp: fruits){

System.out.println("fruits " + ++i + " : " + temp.getFruitName() +

", Quantity : " + temp.getQuantity());

}

}

}

Ordinamento di Array con java.util.Arrays.sort()

Nel precedente esempio si è fatto uso del metodo statico sort della classe java.util.Arrays

per ordinare un array http://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/api/java/util/Arrays.html

public class Arrays

extends Object

This class contains various methods for manipulating arrays (such as sorting and searching). This class also contains a static factory

that allows arrays to be viewed as lists.

The methods in this class all throw a NullPointerException, if the specified array reference is null, except where noted.

Se l'array fruits fosse stato un array di int o di double non ci sarebbe stato alcun bisogno di

implementare l'interfaccia Comparable. Bastava applicare il metodo statico Arrays.sort().

int a[]={30,7,9,20};

Arrays.sort(a);

System.out.println(Arrays.toString(a));

Se l'array fruits fosse stato un array di String si poteva fare l'ordinamento alfabetico ascendente

usando ancora il metodo Arrays.sort()

String[] fruits = new String[] {"Pineapple","Apple", "Orange", "Banana"};

Arrays.sort(fruits);

int i=0;

for(String temp: fruits){

System.out.println("fruits " + ++i + " : " + temp);

}

Output

fruits 1 : Apple

fruits 2 : Banana

fruits 3 : Orange

fruits 4 : Pineapple

Domanda: e se si volesse un ordinamento discendente?

Opzione 1: ridefinire il metodo compareTo in modo da restituire l'opposto di quello che è stato

definito nell'esempio precedente.

Opzione 2: utilizzare la versione di Arrays.sort che ha come input l'array da ordinare e un

comparatore.

static sort(T[] a, Comparator<? super T> c)

Sorts the specified array of objects according to the order induced by the

specified comparator.

L'istruzione per ordinare l'array in modo decrescente è in questo caso:

<T> void

Arrays.sort(fruits, Collections.reverseOrder()); //occore importare

java.util.Collections

I dettagli saranno chiariti nei prossimi paragrafi.

Ordinamento di List con java.util.Collections

La classe java.util.Collections https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/util/Collections.html

This class consists exclusively of static methods that operate on or return collections. It contains

polymorphic algorithms that operate on collections, "wrappers", which return a new collection backed

by a specified collection, and a few other odds and ends.

The methods of this class all throw a NullPointerException if the collections or class objects

provided to them are null.

java.util.Collections contiene alcuni metodi per ordinare liste, come ad esempio gli ArrayList

static sort(List<T> list)

Sorts the specified list into ascending order,

according to the natural ordering of its elements.

static sort(List<T> list, Comparator<?

<T> void super T> c)

Sorts the specified list according to the order

induced by the specified comparator.

<T extends Comparable<? super T>>

void

static void

reverse(List<?> list)

Reverses the order of the elements in the

specified list.

Ad esempio

List<Double> testList=new ArrayList();

testList.add(0.5);

testList.add(0.2);

testList.add(0.9);

testList.add(0.1);

testList.add(0.1);

testList.add(0.54);

testList.add(0.71);

Si può ordinare in senso decrescente con le istruzioni:

Collections.sort(testList); //ordina in senso ascendente

Collections.reverse(testList); //inverte gli elementi

Un ArrayList di oggetti, ad esempio di Fruit, si può ordinare con il metodo Collection.sort

facendo in modo che la classe degli oggetti (Fruit) implementi l'interfaccia Comparable, come nel

precedente esempio. In tal caso si potrà avere un esempio come il seguente:

List<Fruit> fruits= new ArrayList<Fruit>();

Fruit fruit;

for(int i=0;i<100;i++)

{

fruit = new fruit();

fruit.setname(...);

fruits.add(fruit);

}

Per ordinare l'ArrayList basta ora fare

Collections.sort(fruitList);

Collections vs Collection

Attenzione! In Java esiste anche l’interfaccia java.util.Collection (senza la “s” finale) che è

completamente diversa da java.util.Collections. Infatti Collections è una classe contenente

esclusivamente metodi statici di utilità per la manipolazione di oggetti di tipo Collection (o derivati).

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/util/Collections.html

https://docs.oracle.com/javase/8/docs/api/java/util/Collection.html

Ordinamento mediante l'interfaccia java.util.Comparator

Oltre a definire un metodo per effettuare l'ordinamento naturale rispetto a una proprietà con il metodo

compareTo è possibile definire dei comparatori personalizzati che definiscono un ordinamento

mediante condizioni complesse, come riportato nel seguente esempio:

http://java67.blogspot.it/2012/10/how-to-sort-object-in-java-comparator-comparable-example.html

package provacomparator;

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Collections;

import java.util.Comparator;

import java.util.List;

/**

*

* Java program to test Object sorting in Java. This Java program

* test Comparable and Comparator implementation provided by Order

* class by sorting list of Order object in ascending and descending order.

* Both in natural order using Comparable and custom Order using Comparator in Java

*

* @author http://java67.blogspot.com

*/

public class ObjectSortingExample {

public static void main(String args[]) {

//Creating Order object to demonstrate Sorting of Object in Java

Order ord1 = new Order(101,2000, "Sony");

Order ord2 = new Order(102,4000, "Hitachi");

Order ord3 = new Order(103,6000, "Philips");

//putting Objects into Collection to sort

List<Order> orders = new ArrayList<Order>();

orders.add(ord3);

orders.add(ord1);

orders.add(ord2);

//printing unsorted collection

System.out.println("Unsorted Collection : " + orders);

//Sorting Order Object on natural order – ascending

//in questo caso si usa il metodo compareTo ridefinito

Collections.sort(orders);

//printing sorted collection

System.out.println("List of Order object sorted in natural order : " + orders);

// Sorting object in descending order in Java

Collections.sort(orders, Collections.reverseOrder());

System.out.println("List of object sorted in descending order : " + orders);

//Sorting object using Comparator in Java

Collections.sort(orders, new Order.OrderByAmount());

System.out.println("List of Order object sorted using Comparator - amount : " +

orders);

// Comparator sorting Example - Sorting based on customer

Collections.sort(orders, new Order.OrderByCustomer());

System.out.println("Collection of Orders sorted using Comparator - by

customer : " + orders);

}

}

/*

* Order class is a domain object which implements

* Comparable interface to provide sorting on natural order.

* Order also provides couple of custom Comparators to

* sort object based upon amount and customer

*/

class Order implements Comparable<Order> {

private int orderId;

private int amount;

private String customer;

/*

* Comparator implementation to Sort Order object based on Amount

*/

public static class OrderByAmount implements Comparator<Order> {

@Override

public int compare(Order o1, Order o2) {

return o1.amount > o2.amount ? 1 : (o1.amount < o2.amount ? -1 : 0);

}

}

/*

* Anohter implementation or Comparator interface to sort list of Order object

* based upon customer name.

*/

public static class OrderByCustomer implements Comparator<Order> {

@Override

public int compare(Order o1, Order o2) {

return o1.customer.compareTo(o2.customer);

}

}

public Order(int orderId, int amount, String customer) {

this.orderId = orderId;

this.amount = amount;

this.customer = customer;

}

public int getAmount() {return amount; }

public void setAmount(int amount) {this.amount = amount;}

public String getCustomer() {return customer;}

public void setCustomer(String customer) {this.customer = customer;}

public int getOrderId() {return orderId;}

public void setOrderId(int orderId) {this.orderId = orderId;}

/*

* Sorting on orderId is natural sorting for Order.

*/

@Override

public int compareTo(Order o) {

return this.orderId > o.orderId ? 1 : (this.orderId < o.orderId ? -1 : 0);

}

/*

* implementing toString method to print orderId of Order

*/

@Override

public String toString(){

return String.valueOf(orderId);

}

}

11.8 Classi Nested

Nell'esempio precedente la classe Order ha al suo interno due static nested class,

OrderByCustomer e OrderByAmount, che rappresentano i comparatori.

In Java è possibile dichiarare una classe all'interno di un'altra classe per alcuni usi specifici (ad

esempio la creazione di comparatori)

http://docs.oracle.com/javase/tutorial/java/javaOO/nested.html

The Java programming language allows you to define a class within another class. Such a class is

called a nested class and is illustrated here:

class OuterClass {

...

class NestedClass {

...

}

}

Terminology: Nested classes are divided into two categories: static and non-static. Nested

classes that are declared static are called static nested classes. Non-static nested classes are

called inner classes.

class OuterClass {

...

static class StaticNestedClass {

...

}

class InnerClass {

...

}

}

A nested class is a member of its enclosing class. Non-static nested classes (inner classes) have access

to other members of the enclosing class, even if they are declared private. Static nested classes do not

have access to other members of the enclosing class. As a member of the OuterClass, a nested class

can be declared private, public, protected, or package private. (Recall that outer classes can only be

declared public or package private.)

Osservazioni

L'interfaccia Comparator è molto potente in quanto permette di definire diversi criteri di confronto

sulla stessa classe base. Questa interfaccia comprende due metodi astratti compare e equals:

http://docs.oracle.com/javase/7/docs/api/java/util/Comparator.html

Method Summary

Methods

Modifier and Type Method and Description

compare(T o1, T o2)

Compares its two arguments for order.

int

equals(Object obj)

Indicates whether some other object is "equal to" this comparator.

Si noti che una classe che implementa l'interfaccia Comparator deve implementare il metodo

compare, ma non è tenuta a implementare il metodo equals dal momento che ogni classe eredita il

metodo equals di Object e che, come riportato nella documentazione del metodo equals di

Comparator, “ it is always safe not to override Object.equals(Object). ”

boolean

L'interfaccia Comparator trova la sua migliore espressione come classe nested in un'altra classe dal

momento che in questo modo si mantiene la coesione del codice (cohesion): un comparatore ha senso

in quanto definisce una relazione d'ordine su una classe base. Oltre che con l'ausilio di classi statiche

nested, come mostrato nell'esempio della classe Order, è anche possibile utilizzare l'interfaccia

Comparator nel seguente modo:

http://www.mkyong.com/java/java-object-sorting-example-comparable-andcomparator/

import java.util.Comparator;

public class Fruit implements Comparable<Fruit>{

private String fruitName;

private String fruitDesc;

private int quantity;

public Fruit(String fruitName, String fruitDesc, int quantity) {

super();

this.fruitName = fruitName;

this.fruitDesc = fruitDesc;

this.quantity = quantity;

}

public String getFruitName() {

return fruitName;

}

public void setFruitName(String fruitName) {

this.fruitName = fruitName;

}

public String getFruitDesc() {

return fruitDesc;

}

public void setFruitDesc(String fruitDesc) {

this.fruitDesc = fruitDesc;

}

public int getQuantity() {

return quantity;

}

public void setQuantity(int quantity) {

this.quantity = quantity;

}

public int compareTo(Fruit compareFruit) {

int compareQuantity = ((Fruit) compareFruit).getQuantity();

//ascending order

return this.quantity - compareQuantity;

//descending order

//return compareQuantity - this.quantity;

}

public static Comparator<Fruit> FruitNameComparator

= new Comparator<Fruit>() {

public int compare(Fruit fruit1, Fruit fruit2) {

String fruitName1 = fruit1.getFruitName().toUpperCase();

String fruitName2 = fruit2.getFruitName().toUpperCase();

//ascending order

return fruitName1.compareTo(fruitName2);

//descending order

//return fruitName2.compareTo(fruitName1);

}

};

}

Nell'esempio precedente la classe Fruit, oltre a implementare l'interfaccia Comparable per definire

l'ordinamento naturale sugli oggetti della classe Fruit (tramite il metodo compareTo), introduce

anche un campo statico di tipo public static Comparator<Fruit> inizializzato con il riferimento a un

oggetto di una classe anonima che implementa l'interfaccia Comparator<Fruit>, infatti:

FruitNameComparator è inizializzato con il riferimento all'oggetto creato da new

Comparator<Fruit>(){//classe anonima che implementa Comarator<Fruit> e ridefinisce il metodo

compare}

Con la versione precedente della classe Fruit è possibile ordinare un array di Fruit nel seguente modo;

Arrays.sort(fruits, Fruit.FruitNameComparator);

Oppure un ArrayList di Fruit:

Collections.sort(listOfFruit, Fruit.FruitNameComparator);

É anche possibile implementare l'interfaccia Comparator in classi distinte dalla classe base, come

mostrato nel seguente esempio:

http://javahungry.blogspot.com/2013/08/difference-between-comparable-and.html

//Country.java

public class Country{

int countryId;

String countryName;

public Country(int countryId, String countryName) {

super();

this.countryId = countryId;

this.countryName = countryName;

}

public int getCountryId() {

return countryId;

}

public void setCountryId(int countryId) {

this.countryId = countryId;

}

public String getCountryName() {

return countryName;

}

public void setCountryName(String countryName) {

this.countryName = countryName;

}

}

//CountrySortbyIdComparator.java

import java.util.Comparator;

//If country1.getCountryId() < country2.getCountryId():then compare method will return

-1

//If country1.getCountryId() > country2.getCountryId():then compare method will return

1

//If country1.getCountryId()==country2.getCountryId():then compare method will return 0

public class CountrySortByIdComparator implements Comparator<Country>{

@Override

public int compare(Country country1, Country country2) {

return (country1.getCountryId() < country2.getCountryId() ) ? -1:

(country1.getCountryId() > country2.getCountryId() ) ? 1:0 ;

}

}

//ComparatorMain.java

import

import

import

import

java.util.ArrayList;

java.util.Collections;

java.util.Comparator;

java.util.List;

public class ComparatorMain {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Country indiaCountry=new Country(1, "India");

Country chinaCountry=new Country(3, "USA");

Country nepalCountry=new Country(4, "Russia");

Country bhutanCountry=new Country(2, "Japan");

List<Country> listOfCountries = new ArrayList<Country>();

listOfCountries.add(indiaCountry);

listOfCountries.add(usaCountry);

listOfCountries.add(russiaCountry);

listOfCountries.add(japanCountry);

System.out.println("Before Sort by id : ");

for (int i = 0; i < listOfCountries.size(); i++) {

Country country=(Country) listOfCountries.get(i);

System.out.println("Country Id: "+country.getCountryId()+"||"+"Country

name: "+country.getCountryName());

}

Collections.sort(listOfCountries,new CountrySortByIdComparator());

System.out.println("After Sort by id: ");

for (int i = 0; i < listOfCountries.size(); i++) {

Country country=(Country) listOfCountries.get(i);

System.out.println("Country Id: "+country.getCountryId()+"|| "+"Country

name: "+country.getCountryName());

}

//Sort by countryName – utilizzo di un oggetto di una classe anonima

Collections.sort(listOfCountries,new Comparator<Country>() {

@Override

public int compare(Country o1, Country o2) {

return o1.getCountryName().compareTo(o2.getCountryName());

}

});

System.out.println("After Sort by name: ");

for (int i = 0; i < listOfCountries.size(); i++) {

Country country=(Country) listOfCountries.get(i);

System.out.println("Country Id: "+country.getCountryId()+"|| "+"Country

name: "+country.getCountryName());

}

}

}

Talvolta è utile effettuare la conversione tra ArrayList e Array e viceversa

11.9 Convertire un ArrayList in un Array

ArrayList class has a method called toArray() that we are using in our example to convert it into

Arrays.

Following is simple code snippet that converts an array list of countries into string array.

List<String> list = new ArrayList<String>();

list.add("India");

list.add("Switzerland");

list.add("Italy");

list.add("France");

String [] countries = list.toArray(new String[list.size()]);

So to convert ArrayList of any class into array use following code. Convert T into the class whose arrays you want

to create.

List<T> list = new ArrayList<T>();

T [] countries = list.toArray(new T[list.size()]);

11.10 Convertire ArrayList in Array

Vediamo il seguente esempio:

http://viralpatel.net/blogs/convert-arraylist-to-arrays-in-java/

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.List;

import java.util.Arrays;

String[] countries = {"India", "Switzerland", "Italy", "France"};

List list = Arrays.asList(countries);

System.out.println("ArrayList of Countries:" + list);

The above code will work great. But list object is immutable. Thus you will not be able to add new values to it. In

case you try to add new value to list, it will throw UnsupportedOperationException.

Related: Resolve UnsupportedOperationException exception

Thus simply create a new List from that object. See below:

String[] countries = {"India", "Switzerland", "Italy", "France"};

List list = new ArrayList(Arrays.asList(countries));

System.out.println("ArrayList of Countries:" + list);

12 Interfacce Grafiche (GUI)

12.1 Elementi di un'interfaccia grafica