Sommario / Contents

3

Editoriale

Focus On

7

Il ritorno della «Juive»

L’opera di Halévy apre la stagione della Fenice

The return of the «Juive»

Halévy’s opera opens the season at the Fenice

di / by Emilio Sala

9

L’intrattenimento morale di Scribe

7

Maestro del «vaudeville» firmò una produzione sterminata

Scribe’s moral entertainment

The «vaudeville» maestro signed an infinite production

10

Eléazar, ebreo fanatico vittima di se stesso

Il tenore Neil Shicoff racconta il suo personaggio nella «Juive»

Eléazar, a fanatic Jew who falls victim to himself

The tenor Neil Shicoff talks about his character in «Juive»

di / by Enrico Bettinello

14

Il magico talento di Frédéric Chaslin

Direttore e pianista, un astro in costante ascesa

The enchanted talent of Frédéric Chaslin

Conductor and pianist, a star that won’t stop rising

15

Fenice, una stagione ricca e drammatica

«Rischiamo di perdere il nostro primato di grandi creatori d’opera»

Fenice, an intense and dramatic season

10

«We risk losing our primacy as the great creators of opera»

da una conversazione con / from a conversation with Sergio Segalini

17

«I tagli faranno sparire metà stagione»

Il sovrintendente Vianello sulle ripercussioni della Finanziaria

«The cuts will mean half the season disappears»

Superintendent Vianello talks about the Financial bill

18

Il generoso gesto di Kitajenko

Il maestro ha rinunciato al cachet per protesta contro i tagli

The generous gesture by Kitajenko

The maestro foregoes his fee in protest against the cuts

20

Teatro: sempre più impresa e meno cultura

Dalla riduzione del Fus all’assenza di mecenatismo

Theatre more as a business and with less culture

From the reduction of contributions to the lack of patrons

di / by Mario Messinis

All’Opera

22

Trieste, dalla «Turandot» alla «Bohème»

24

I «Pagliacci», amore-morte tra scena e realtà

25

Il colore esotico delle turcherie

24

Il direttore del Teatro Verdi illustra la prossima stagione

da una conversazione con Daniel Pacitti

Il capolavoro di Ruggero Leoncavallo conquista Rovigo

Al Comunale di Treviso «L’Italiana in Algeri» di Rossini

di Martina Buran

La cornice sinfonica

27

La musica antica incontra i suoni del mondo

28

Alla Fenice una rara sonata di Fano

29

Da Schubert a Chopin, venti concerti a Padova

31

Treviso brilla con Carmignola e Sokolov

Al Malibran il suggestivo concerto dell’Ensemble Hesperion XXI

di Arianna Silvestrini

28

Il 5 dicembre anche brani «storici» di Casella e Pizzetti

di Chiara Squarcina

Il fitto programma della LXI stagione degli Amici della Musica

di Filippo Juvarra

Ricca e di gran richiamo la sesta stagione della Marca

Sacro e barocco

33

Musica sotto le volte della Salute

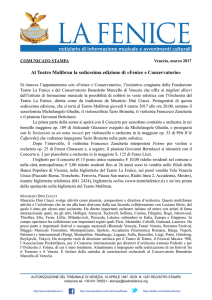

34

Frari: 1 cd, 2 organi e 35 anni di musica

4

I concerti in Basilica nel periodo della festa più veneziana

di Paola Talamini

La stagione concertistica raccontata dall’organista titolare

di Chiara Squarcina

34

Sommario / Contents

Note veneziane

38

L’Ateneo Veneto ha aperto le porte alla musica

39

Una Fenice per Uto Ughi e l’Airc

40

Rubelli «veste» la Fenice per i suoi cinquant’anni di attività

Cento eventi in quattro anni voluti dal presidente Alfredo Bianchini

Mondanità e beneficenza al concerto organizzato da Vittorio Coin

In scena il «Mitridate» di Porpora con i tessuti dell’azienda

Contemporanea

41

«Risonanze» pop & jazz

Nuove sonorità al Teatro Fondamenta Nuove

di Massimo Ongaro

40

L’altra musica

43

Bella e brava, tutti pazzi per Natalie

44

L’ora dei Balcani

46

Simply Red, concerto e nuovo album

47

Il «matematico» con la chitarra jazz

48

Musica, l’altra faccia delle emozioni

48

San Servolo, isola a tutto jazz

La Imbruglia porta in Veneto i suoi ultimi lavori

di Tommaso Gastaldi

La musica di Bregovic tra tradizione e sperimentazione

di Andrea Dusio

44

Lanfranco Malaguti racconta la sua musica

di Guido Michelone

A San Servolo un convegno sul rapporto tra cervello e note

di Massimiliano Goattin

Tra Triangulation e Metamorfosi Trio fino al 24 novembre

di Massimiliano Goattin

In vetrina

51

Bob Dylan, quando una storia è senza fine

Due soli concerti in Italia del «patrimonio dell’umanità»

di John Vignola

Dintorni

52

L’«Urfaust» secondo Andrea Liberovici

53

«Il Campiello» tra populismo e folklore

54

Un matrimonio senza emozioni e senza regole: ma accettato con brio!

55

Cenni per una grammatica corpoorale

57

Tintoretto riscoperto

Marionette, diavoli e suoni con Paola Gassman e Ugo Pagliai

51

Nella commedia di Goldoni il rigore documentario nella descrizione del popolo

di Bruno Rosada

Maria Amelia Monti protagonista di «Ti ho sposato per allegria»

di Carmelo Alberti

Alla Biennale gli Ortographe, gruppo di punta del teatro italiano

di Amerigo Nutolo

In mostra opere appartenenti alla collezione del Patriarca

di Andrea Dusio

Carta Canta

58

Pizzi, genio e passione nella scenografia

59

Tutto Puccini in settecento pagine

60

Teatro archetipico e fiabesco

61

«The Return», scenografia acustica e visiva

63

65

69

70

Zoom

Appuntamenti / Events

Il Veneto in musica

Dopo lo spettacolo / After the performance

57

Un libro dedicato al mezzo secolo di lavori del regista in Fenice

L’opera di Marcel Marnat dedicata al grande compositore

di Silvano Onda

In volume il percorso tra boschi e angeli di Giuliano Scabia

Straordinario cd del film vincitore alla Mostra nel 2003

60

5

In copertina:

La Juive, allestimento realizzato dalla

Wiener Staatsoper.

VeneziaMusica e dintorni

Anno II – n. 7 – novembre / dicembre 2005

Periodico bimestrale

Reg. Tribunale di Venezia n. 1496 del 19 / 10 / 2004

Editore: Euterpe Venezia s.r.l.

Direttore responsabile: Manuela Pivato

Progetto e direzione editoriale: Leonardo Mello

Caporedattore: Ilaria Pellanda

Segreteria di redazione: Erica Molin e Catia Munari

Progetto e realizzazione grafica: Roberta Volpato

Stampa: Grafiche Crivellari – Ponzano Veneto (TV)

Redazione: Dorsoduro 3488/U – 30123 Venezia

tel. 041 715188 / 041 719274 – fax 041 2753231

e-mail: [email protected]

web: www.euterpevenezia.it

Raccolta pubblicitaria: Promoeditorial – [email protected]

Nicoletta Echer (348 3945295) – Roberto Echer (347 7206625)

Prezzo unitario: 3 Euro

Abbonamento a sei numeri: 15 Euro

tramite conto corrente postale n. 62330287

intestato a: Euterpe Venezia s.r.l.

per informazioni contattare la redazione

Tiratura: 4500 copie

Contributi di Emilio Sala, Enrico Bettinello, Mario Messinis, Martina Buran,

Arianna Silvestrini, Chiara Squarcina, Filippo Juvarra, Paola Talamini,

Massimo Ongaro, Tommaso Gastaldi, Andrea Dusio, Guido Michelone,

Massimiliano Goattin, John Vignola, Bruno Rosada, Carmelo Alberti,

Amerigo Nutolo, Silvano Onda

Traduzioni di Tina Cawthra

Si ringraziano Mario Messinis, Neil Shicoff, Emilio Sala, Giovanni Morelli,

Barbara di Valmarana, Sergio Segalini, Giampaolo Vianello, Daniel Pacitti,

Nicoletta Cavalieri, Andrea Liberovici, Massimo Ongaro, Roberto Masotti,

Veniero Rizzardi, Alfredo Bianchini, Yaya e Vittorio Coin, Margherita Gianola,

Filippo Juvarra, Fabio Achilli, Stefano Bortoli, Alessandro Favaretto Rubelli,

Chiara Squarcina, Enrico Bettinello, Bruno Rosada, Carmelo Alberti,

Guido Michelone, John Vignola, Amerigo Nutolo, Andrea Dusio, Paola Talamini,

Silvano Onda, Arianna Silvestrini, Massimiliano Goattin, Martina Buran,

Eva Rico, Franco Quadri, Maryon Pessina, Marina Pellanda, Alberto Santini,

Roberto Stefani, Daniela Martinello, Paola Maritan, Barbara Montagner,

Monica Fracassetti, Mariateresa Biasio, Luisa Bassetto, Cristina Moschioni,

Francesca Arduini, Loredana Di Pascale, Gregorio Bacci, Lisa D’Amico,

Mauro Levorato e i ragazzi del Caffè Rosso, Carmen e Pitù

Si ringrazia particolarmente Ursula Lissen per il prezioso aiuto alla realizzazione

dell’intervista con Neil Shicoff

Si ringrazia inoltre il Teatro La Fenice di Venezia per l’immagine di copertina

Photocredits: Wiener Staatsoper GmbH / Axel Zeininger, 8-10; Universität zu

Köln, 22-.23; 24; Österreichischer Bundestheaterverband – Vienna, 25; Margherita

Gianola, 34-35; Manuel Silvestri, 38; Bepi Caroli, 52; Pietro Castellucci, 55;

Vladimir Mishukov, 61

Elenco degli inserzionisti: Saccaim, 2; Ristorante Antico Martini, 23; Fondazione

Benetton, 26; Allemandi, 30; Altra Musica, 31; Hotel Monaco & Grand Canal,

32; Vetreria Artistica Archimede Seguso, 36-37; Terrazza Orseolo, 42; Hotel

Giorgione, 50; Bottega d’Arte S. Vio, 56; Duodo Palace Hotel, 62; Margerie, 64;

Bugno Art Gallery, terza di copertina; Cassa di Risparmio di Venezia, quarta di

copertina

VeneziaMusica e dintorni si può trovare presso: Associazione Culturale Spiazzi,

Castello 3865, Venezia; Bottega d’Arte San Vio, Dorsoduro 720/B, Venezia; Caffè

Rosso, campo Santa Margherita, Venezia; Libreria Cafoscarina, Dorsoduro 3259,

Libreria Goldoni, San Marco 4742, Venezia; Libreria IUAV-Tolentini, Santa Croce

191, Venezia; Libreria Mondadori, San Marco 1345, Venezia; Libreria Toletta,

Dorsoduro 1213, Venezia; Cantinone Già Schiavi, Dorsoduro 992, Venezia;

Discoland, campo San Barnaba, Venezia; Teatro Fondamenta Nuove, cannaregio

5013, Venezia; Vivaldi Store/Nalesso, San Marco 5537; Effe Bi Musica, via

Cardinal Massaia 35, Mestre; Libreria Feltrinelli, piazza XXVII Ottobre 1, Mestre;

Zydeco sas, via verdi 43, Mestre; Musica e Suono, via Galilei 2, Portogruaro;

Cartolibreria Marton, Corso del Popolo 40, Treviso

6

Focus On

Il ritorno della «Juive»

L’opera di Halévy apre la stagione della Fenice

The return of the «Juive»

Halévy’s opera opens the season at the Fenice

di / by Emilio Sala*

M

olti penseranno trattarsi di un repêchage, tra l’archeologico e l’iperspettacolare. Tipo il Salieri

scaligero dell’anno scorso. Niente di tutto ciò. Semmai

ci troviamo di fronte a un tentativo di riappropriazione.

L’ebrea di Halévy (1835), un po’ come gli Ugonotti di

Meyerbeer (1836), ha segnato profondamente il mondo

operistico ottocentesco, diventando un successo popolare e internazionale. Percorsa l’Europa, La juive varcò

ben presto l’oceano (New York 1845, Montevideo 1853,

Buenos Aires 1854). In Italia fu introdotta in ritardo, a

Genova, nel 1858. Per più di mezzo secolo venne regolarmente applaudita dal pubblico borghese della penisola e del mondo intero. Poi, ad un certo punto, verso la

prima guerra mondiale (durante l’affermarsi dei totalitarismi), l’oblio. Tenendo presente che tanto Meyerbeer

quanto Halévy sono ebrei

e che i loro due capolavori

mettono in musica e in scena

fenomeni di persecuzione e

intolleranza collettive, vien

fatto di chiedersi se si tratta

di oblio o se non piuttosto di

rimozione…

D’altronde,

l’ambivalenza

nei confronti degli ebrei è

evidente anche in un’opera

di chiaro segno «illuminista».

Rachel, la bella «juive» del

titolo, si rivela alla fine una

cristiana. L’identificazione

del pubblico è così, retrospettivamente, assai meno

disagevole. Un «romanzo

popolare» pubblicato a

Milano nel 1891 (L’ebrea di

Mario Mariani), una sorta di

parafrasi narrativa del libretto di Scribe (ma anche della

musica di Halévy) e prova vivente del grande successo dell’opera, appare esemplare

al riguardo. In esso, infatti, il pregiudizio contro quella

«disgraziata razza» (la quale «ancor oggi, non ostante

le molte pretese della nostra civiltà, è, in molti luoghi,

tenuta lontano dai pubblici uffici») è sì duramente condannato. Ma l’antisemitismo cacciato dalla porta rientra

dalla finestra quando viene descritta l’avidità di Eleazaro, il padre (che scopriremo adottivo) di Rachele, i cui

occhi «brillano di cupidigia» alla presenza di un buon

affare, secondo l’antico stereotipo che va da Shylock a

Ebenezer Scrooge.

M

any will think it is just a repêchage, a mix of the

archaeological and hyper-spectacular. Just like the Salieri

at the Scala last year. Nothing could be further from the truth.

If anything, we find ourselves in front of an attempt of re-appropriation. The Jewess by Halévy (1835), a little like the

Ugonotti by Meyerbeer (1836), left a profound mark on the

nineteenth century opera world, becoming a general and international success. After being performed in Europe, La Juive soon

crossed the Atlantic (New York 1845, Montevideo 1853, Buenos Aires 1854). It was introduced in Italy much later in Genoa

in 1858. For over half a century audiences in the peninsula and

throughout the world regularly applauded it. Then, at a certain

point, around the time of the First World War (when totalitarianism established itself), it fell

into oblivion. In view of the fact

that both Meyerbeer and Halévy

are Jewish and that their two

masterpieces put the phenomena

of collective persecution and intolerance to music and on the set, one

can ask oneself if it is a case of

oblivion or displacement…

On the other hand, the ambivalence towards the Jews can also

be seen in an opera of a clearly

«enlightened» nature. Rachel, the

beautiful «juive» of the title, is

shown to be a Christian at the

end. Thus, retrospectively, the

identification of the audience is

much less awkward. A «popular

novel» published in Milan in

1891 (The Jewess by Mario

Mariani), is a sort of narrative

paraphrasing of the libretto by

Scribe (but also of Halévy’s music) and the living evidence of the

opera’s resounding success would

seem exemplary of this fact. Indeed, in it the prejudice against

that «wretched race» (which,

«despite the great claims of our civilisation is still kept at a distance from public offices in many places») is severely condemned.

However, the anti-Semitism that is banished from one window

comes back in through another when the avidness of the Rachel’s

father, Eleazaro (who turns out to have adopted her) and whose

eyes «gleam with greed» when he scents a bargain, following the

ancient stereotype that goes from Shylock to Ebenezer Scrooge.

However, leaving aside the aspect of displacement, the cultural

importance of Halévy’s La Juive is demonstrated in various

ways. It suffices to think of the «Rachel quand du Seigneur»

of Proust’s Recherche. Wagner himself, as is known (all

«Per più di mezzo secolo

“L’ebrea” di Halévy venne

regolarmente applaudita

dal pubblico borghese del

mondo intero.

Poi, ad un certo punto,

durante l’affermarsi dei

totalitarismi, l’oblio»

«“The Jewess” by Halévy for

over half a century audiences

throughout the world regularly

applauded it.

Then, at a certain point, when

totalitarianism established itself, it

fell into oblivion.»

7

Focus On

too well), repeatedly praised La juive. But what I find even

more significant is the obvious relational link that unites the

two fabulae – that of the Juive and that of the Trovatore.

It is also interesting to note that Verdi saw Halévy’s opera in the

Grande Boutique of Paris, during his first visit to the French

capital in September 1847. Rachel is to the Jew Eléazar what

Manrico is to the gypsy Azucena. The sound of the anvil,

present in both scores (as well as in Wagner’s Siegfried), evokes

the restless world of the outcast – unimportant whether gypsies

or Jews. Eléazar also saw his children burnt at the stake and despite his obsessive desire for revenge, he loves a daughter (Rachel)

with fatherly love, who is not his blood and whom he kidnaps

one day in mysterious circumstances from Cardinal Brogni.

The climax with which both operas end is basically the same.

Azucena says «Egl’era tuo fratel!» [He was your brother!] to

Count Luna while Manrico is being executed just as Eléazar

says to Cardinal Brogli «La voilà!»[ (ell’era figlia tua!) [she was

your daughter] while Rachel is thrown into the «dans la cuve

bouillante».

In short, although today we are used to enjoying operas that are

placed one by one in a repertoire (fortunately one that is constantly

being expanded) as if they were unrelated and decontextualised

monads like museum pieces, the return of La Juive is not just

one more title to be conserved, but the possibility to reconstruct

an important part of connective fabric. It is an opportunity not

only to reactivate the fundamental link of the nervous system to

that of melodramatic imagination, which, despite everything, still

exists in each one of us.

Comunque sia, questione della rimozione a parte, l’importanza culturale della Juive di Halévy è variamente

testimoniata. Basti pensare alla «Rachel quand du Seigneur» della Recherche proustiana. Lo stesso Wagner,

com’è (fin troppo) noto, lodò a più riprese La juive. Ma

ciò che mi sembra ancor più significativo è l’evidente

legame di parentela che unisce le due fabulae – quella

della Juive e quella del Trovatore. In questo quadro, può

essere interessante segnalare che Verdi vide l’opera di

Halévy nella Grande Boutique di Parigi, durante il suo

primo viaggio nella capitale francese, nel settembre

1847. Rachel sta all’ebreo Éléazar come Manrico alla

zingara Azucena. Il suono dell’incudine, presente in

entrambe le partiture (nonché nel Siegfried wagneriano),

rinvia all’inquietante mondo degli emarginati – zingari

o ebrei poco importa. Anche Éléazar ha visto perire i

suoi figli sul rogo e, nonostante l’ossessivo desiderio di

vendetta, ama d’amor paterno una figlia (Rachel) che

non è sua e che egli rapì un giorno, in circostanze misteriose, al Cardinale Brogni. Il colpo di scena che chiude

entrambe le opere è sostanzialmente lo stesso. Azucena

dice «Egl’era tuo fratel!» al Conte di Luna mentre Manrico viene giustiziato esattamente come Éléazar dice al

Cardinale Brogni «La voilà!» (ell’era figlia tua!) mentre

Rachel viene gettata «dans la cuve bouillante».

Insomma, anche se oggi siamo abituati a fruire di opere

collocate una per una in un repertorio (fortunatamente

in fase di continuo allargamento) come se fossero delle

monadi irrelate e decontestualizzate, a mo’ di museo, il

recupero della Juive non significa solo un titolo in più

da mettere sottovetro, ma la possibilità di ricostruire un

pezzo importante di tessuto connettivo. Un’occasione

per riattivare uno snodo fondamentale del circuito

nervoso di quell’immaginazione melodrammatica che,

nonostante tutto, abita ancora dentro di noi.

* Associato di Drammaturgia musicale e di Fondamenti

di storiografia musicale presso l’Università degli Studi

di Milano.

Ø

8

La Juive, Wiener Staatsoper

Focus On

L’intrattenimento morale di Scribe

Maestro del «vaudeville» firmò una produzione sterminata

Scribe’s moral entertainment

The «vaudeville» maestro signed an infinite production

A

Le Prophète

N

ue

ug

Les H

on sono molti, oltre alla Juive, i libretti d’opera

di Eugène Scribe (1791-1861), il mago del vaudeville, che solo tra il 1815 e il 1830 ha composto ben

148 commedie brillanti, divenendo una stella del teatro

d’intrattenimento, maestro riconosciuto dentro e fuori

della Francia. All’interno della sua opera si possono

comunque isolare due percorsi. Il primo, che arriva fino

al 1850, tende esclusivamente a divertire il pubblico,

affollando le pièce di battute ad effetto e colpi di scena.

Il secondo invece, sviluppato nel periodo della maturità

– pur rispettando le regole drammatiche dei vari generi,

che vanno appunto dal vaudeville al dramma al libretto

d’opera e comprendono tutta la gamma di possibilità

offerte a un autore teatrale – tenta di descrivere attraverso i testi drammatici la vita contemporanea, fornendo

spaccati della società parigina e aprendosi a un certo

grado di realismo. Soprattutto all’interno del vaudeville si

percepisce questa sua opera riformatrice, che colora le

pièce di considerazioni e spunti morali oltre che di crude

descrizioni a sfondo sociale. Nella sua sterminata produzione, Scribe contribuisce anche a trasformare l’opéracomique in vero e proprio dramma musicale, fornendo

a musicisti del calibro di Donizetti, Halévy, Auber e

Meyerbeer libretti a sfondo storico tra cui Robert Le

Diable (1831), Les Huguenots (1836) e Le Prophète (1849).

Fortemente antiromantico e da molti accusato di simpatie per Luigi Filippo, Scribe per molto tempo dovette

risentire dei pregiudizi sulla sua persona, che si riverberarono anche sulla sua opera. Ma almeno per il ventennio 1830-1850 fu il più famoso autore drammatico

del mondo occidentale, e non solo, se è vero l’aneddoto

che vuole una sua commedia, Michel et Christine, recitata

davanti all’imperatore cinese. Nell’ultimo decennio della

sua vita, tuttavia, pur non cessando di scrivere assiduamente, il suo astro – ancora splendente all’estero – in

patria venne offuscato dalle nuove personalità letterarie

che vi si affacciavano, tra cui Sardou, Augier e soprattutto Dumas fils. (l.m.)

part from La Juive, Eugène Scribe (1791-1861) did

not write many opera libretti. He was a magician of

vaudeville, writing no less than 148 brilliant comedies between

only 1815 and 1830, thus becoming a star of the theatre of

entertainment, and a maestro who was recognised both in France

and beyond. However, his work follows two different paths. The

first, which goes up to 1850, tends towards the exclusive enjoyment

of the audience, with a multitude of jokes and coup de theatre.

The second, however, which was developed during his mature period, respects the dramatic rules of the various genres the author

deals with – ranging from vaudeville to drama to opera librettos, including the whole range of possibilities at a theatre author’s

disposal – and he tries to describe contemporary life using the

dramatic texts, offering insights into Parisian society and with a

certain degree of realism. In his vaudeville in particular, one can

feel this reforming work, which colours the pièce with moral considerations and views, together with harsh descriptions of a social

nature. In his infinite production, Scribe also plays his role in the

transformation of opéra-comique into true musical drama, providing outstanding musicians such as Donizetti, Halévy, Auber and

Meyerbeer with historically based libretti including Robert Le

Diable (1831), Les Huguenots (1836) and Le Prophète

(1849). Strongly anti-romantic and accused by many of sympathising with Louis Philippe, for a long time Scribe suffered from

considerable prejudice, which also made itself felt in his work.

However, for the twenty year period from 1830 to 1850 he was

the most famous drama author in the western world and beyond,

if it is true that one of his comedies, Michel et Christine, was

performed before the Chinese emperor.

During the last decade of his life,

however, while never ceasing

to write assiduously, his

star – which was still

shining high abroad

– was outshone in his

homeland by the appearance of new literary figures including Sardou, Augier

and Dumas fils in

particular.

(l.m.)

no

ts

9

Focus On

Eléazar, ebreo fanatico vittima di se stesso

Il tenore Neil Shicoff racconta il suo personaggio nella «Juive»

Eléazar, a fanatic Jew who falls victim to himself

The tenor Neil Shicoff talks about his character in «Juive»

A

interpretare il tormentato personaggio di Eléazar nella

Juive di Halévy che aprirà la stagione lirica della Fenice

è uno tra i più importanti tenori americani della sua generazione, il newyorkese Neil Shicoff, che dal debutto a Cincinnati di

trent’anni fa ha affrontato con grande successo un vastissimo numero di ruoli, grazie all’intensità e alla liricità della propria voce.

La Juive è opera con cui ha una notevole familiarità ed è proprio

da qui che abbiamo dato inizio a una piacevole chiacchierata.

Lei sta interpretando già da tempo il personaggio di Eléazar

in La Juive. Quali difficoltà e quali stimoli offre questa figura

a un tenore?

Devo premettere che non mi interessano le parti

romantiche, non sono un eroe. Amo i personaggi

complessi, paranoici (quelli che io chiamo i «broken

characters»), che stimolano la mia fantasia e nei quali

mi identifico. È un gioco pericoloso, perché dopo la

recita bisogna «ritornare» e spesso non si riesce. Nel

caso di Eléazar il coinvolgimento emotivo è il maggior

problema: a volte mi capita che per tutta la giornata successiva alla recita non mi riprendo e cammino persino

curvo e trascinando le gambe, come il vecchio ebreo.

Lo stimolo che trovo nella parte di Eléazar è la possibilità di trasmettere un messaggio, anche politico – La Juive

Neil Shicoff

10

T

di / by Enrico Bettinello

he opera season of the Fenice is to be opened with

the performance of the Juive by Halèvy, with the

tormented character of Eléazar to be played by one of

the most important American tenors of his generation,

the New Yorker Neil Schicoff, who made his debut in

Cincinnati thirty years ago and has successfully had an

endless number of roles, thanks to the intensity and lyricism of his voice. La Juive is an opera he is very familiar

with and it is with this that we started our extremely

pleasant chat. You have been playing the character of

Eléazar in La Juive for some time now. What difficulties

and stimulus does this figure have for a tenor?

I’d like to start by saying that I’m not interested in romantic

parts; I’m not a hero. I love complex, paranoid characters (what

I call «broken characters»), that stimulate my imagination and

that I can identify with. It’s a dangerous game because after the

performance you have to «return», and often it’s not possible. In

the case of Eléazar, emotional involvement is the greatest problem: sometimes I find that for the whole day after the performance

I don’t recover and I even walk buckled over and dragging my legs,

like the old Jew. The stimulus I find in the part of Eléazar is the

possibility of transmitting a message – also political – La Juive

is a political opera and of all operas is probably the most current

Focus On

La Juive, New Israeli Opera

è un’opera politica e di tutte le opere, forse la più attuale

nel mondo di oggi – e il messaggio è che il fanatismo e

l’intolleranza non pagano e che la mancanza di dialogo

tra persone o popoli porta con sé tremende conseguenze. Alla fine – e non solo nel finale della Juive – sono

tutti perdenti. L’abbiamo sotto gli occhi ogni giorno,

dappertutto nel mondo.

Talvolta mi si rimprovera di rendere Eléazar troppo

«umano», non abbastanza cattivo. È il mio personale

modo di vedere un personaggio che non è certamente

simpatico. È un fanatico, un uomo incatenato e dilaniato dall’odio e questo odio lo spinge sino al sacrificio

della propria figlia. Ma è, comunque, una vittima e la

sua sofferenza è proporzionale alla violenza del suo

carattere!

Il ruolo di Eléazar è stato in passato un cavallo di battaglia di

tenori come Caruso, Tucker, Slezak. Cosa ha tratto da quelle

memorabili interpretazioni?

Caruso ha cantato Eléazar verso la fine della sua vita,

quando già era sofferente e questo ha dato grande

pathos alla sua interpretazione. Slezak ha cantato il

miglior recitativo di tutti e Tucker, essendo ebreo, è

probabilmente quello che ha trovato la migliore identificazione. Questa combinazione di pathos, espressione

e identificazione sarebbe la perfezione, la «summa» di

una grande interpretazione e mi è servita da ispirazione

e insegnamento. Vocalmente parlando tutti e tre i suddetti tenori erano tenori eroici. La mia voce è invece

più lirica e il mio approccio lo è quindi di conseguenza.

Del resto ho potuto sentire soltanto in disco quelle voci

meravigliose (a parte Tucker) e ai loro tempi l’allesti-

in today’s world – and the message

is that fanaticism and intolerance

are rewarded and that the lack of

communication between people(s)

has terrible consequences. In the end

– and not just in the finale of the

Juive – they are all losers. We can

see the same thing everyday, all over

the world.

Sometimes I am criticised for making Eléazar too «human», not evil

enough. It’s my own personal way of

seeing a character that is anything

but nice. He’s a fanatic, enchained

and tormented by hate, and this hate

even pushes him to sacrifice his own

daughter. However, he is still a victim and his suffering is proportional

to the violence of his character.

In the past, the role of Eléazar

has been a warhorse of tenors

such as Caruso, Tucker and

Slezak. What attracted you in

those memorable performances?

Caruso sang Eléazar towards the

end of his life, when he was already

suffering and this gave immense pathos to his performance. Slezak sang

the best recitative of all of them and

Tucker, being Jewish, was probably

the one who was able to identify

himself with the character the best.

This combination of pathos, expression and identification would

be the perfection, the «total» of a great performance and it gave

me both inspiration and served me as a lesson. Vocally speaking,

all the three aforementioned tenors were heroic tenors. But my

voice is more lyrical and as a result so is my approach. Furthermore, I’ve only been able to listen to those marvellous voices on a

record (apart from Tucker) and in those times the production was

traditional.

A propos production, which details will we enjoy in this

production of the opera by Halévy?

Compared to the traditional productions, this Juive is completely

different: we aren’t at the beginning of the fifteenth century, here

Eléazar is a persecuted Jew wearing a yellow star, and in the

background is the holocaust! The production is modern but it isn’t

set in a specific period, it’s sort of timeless. Let’s see whether the

Venetian audience appreciates this choice or not!

Apart from that of Eléazar, which roles are you particularly fond of ? Which would you like to play or repeat

because you think they can give new inspiration?

The opera I’ve sung most often is The Tales of Hoffmann,

starting in Florence in 1980, in the production by Luca Ronconi,

and if I had to choose a character I’d like to be remembered for,

it’s as Hoffmann! It’s another of those «broken characters» that

fascinate me. I’ve sung it countless times, in opera houses all over

the world, even in La Scala in Milan in 1995 and the last time

was two years ago at the Salzburg Festival. Peter Grimes is

another opera I will always sing, and then obviously there’s also

La Juive. These are characters you go on exploring. I’ve always

put off La dama di picche because it’s so difficult vocally, but

I can’t wait to sing German. There’s a project in the air for that.

Then, of course there’s Verdi, for the voice …

11

Focus On

mento era tradizionale.

A proposito, quali particolarità apprezzeremo in questo allestimento dell’opera di Halévy?

Rispetto agli allestimenti tradizionali, questa Juive è molto diversa: non siamo all’inizio del Quattrocento, Eléazar è qui l’ebreo perseguitato, con la stella gialla, e sullo

sfondo c’è l’Olocausto. L’allestimento è moderno, ma

non è ambientato in un’epoca specifica, è come fuori

dal tempo. Vedremo se il pubblico veneziano apprezzerà o meno questa scelta!

Oltre a quello di Eléazar, quali sono i ruoli cui è più legato?

Quali quelli che vorrebbe interpretare o reinterpetare perché ritiene possano suggerire nuovi spunti?

L’opera che ho cantato di più è I Racconti di Hoffmann,

a partire dal 1980 a Firenze, con la regia di Luca

Ronconi, e se dovessi scegliere un personaggio per

cui vorrei essere ricordato, mi piacerebbe essere ricordato come Hoffmann! È un altro di quei «broken

characters» che mi affascinano. L’ho cantato un’infinità di volte, in tutti i teatri del mondo, anche alla

Scala di Milano nel 1995 e l’ultima volta due anni fa

al Festival di Salisburgo. Peter Grimes è un’altra opera

che canterò sempre e poi c’è naturalmente La Juive.

Sono personaggi che non si finiscono mai di esplorare.

Ho sempre rimandato La dama di picche, perchè vocalmente è molto pesante, ma attendo ansiosamente di

cantare German. C’è un progetto in tal senso. Poi ci

sarà, naturalmente, Verdi, per la voce…

Quali qualità le ha portato la familiarità con una modalità

come quella cantoriale di cui suo padre Sidney è stato un grande

Which qualities made you familiar with cantorial canto

such as the one of which your father Sidney was such

a great exponent?

I only studied under my father for a short while because he died

when I was just sixteen, but he will always be with me. In the second act of the Juive, I use the cantorial canto, which I regard

as a further means of expression and enrichment.

You made your début as Ernani and have frequently

performed works by Verdi. Which roles do you think

are most suited to your expressive characteristics?

Verdi is a real heal-all for the voice! Before any performance I

always warm my voice up singing half of Un ballo in maschera!

I made my debut with Ernani when I was really young and reckless because I replaced Richard Tucker at the last minute when

he died. Then I put Ernani aside and made my debut at the

Metropolitan as Rinuccio in Gianni Schicchi. I went back to

Ernani much later and I still sing it. I’ve sung both Il trovatore

and Un ballo in maschera many times. However, I do believe

that Don Carlo and Luisa Miller are the two operas by Verdi

that are best suited to me.

In Italy there is the fear of considerable cuts to funding

for the opera. What do you think and what does your

international experience tell you?

It is a bad and shortsighted decision; it’s a great disappointment.

The foundation of our civilisation is culture, music; it’s something

that hardly needs to be pointed out in a country with a history

such as Italy’s. Private parties will need to intervene more with

sponsorships and donations, the way they do in America.

Which Italian opera houses do you like most?

I’ve sung in many Italian opera houses and I must say that I’m

La Juive, New Israeli Opera

12

Focus On

equally at ease in all of them. But I must admit

– and I’m not saying it deliberately – that I am

particularly happy about my return to the Fenice where I sang frequently before the fire. It

was terrible when La Fenice was destroyed

so my joy now it has risen once more is so

much greater.

What are your next commitments

and projects for the future?

My most important commitments are

in January 2006 with Idomeneo

in a new production of the Vienna

Staatsoper, then in July in Cagliari

with Manon Lescaut and in September the opening of the Metropolitan. In

2007 I’ll be working on Britten’s Death

in Venice for a new production in Vienna, then in Salzburg in the summer and

autumn on a new production of La Juive

in Paris. In 2008 there’s a new production

at the Metropolitan with Peter Grimes and

lév there are also projects for a Benvenuto Cela

lH

lini. As you can see, I’ve never had so many new

enta

m

o

r

F

operas in my life in my repertoire as now. I have to

study a lot, but you need new operas so you don’t get bored.

My career began over thirty years ago and I can’t imagine just

going on singing only La Bohème.

y

esponente?

Ho studiato con mio padre per breve

tempo, perché è morto quando avevo

solo sedici anni, ma lo porto dentro

di me, sempre. Nel secondo atto

della Juive uso proprio il cosiddetto canto cantoriale, che ritengo

un ulteriore mezzo di espressione e di arricchimento.

Lei ha debuttato con Ernani e ha

spesso affrontato il repertorio verdiano. Quali pensa siano i ruoli che

meglio si attagliano alle Sue caratteristiche espressive?

Verdi è un vero toccasana per

la voce! Prima di ogni mia recita riscaldo regolarmente la voce

cantando mezzo Un ballo in maschera! Ho debuttato giovanissimo

e incosciente con Ernani, perchè

ho sostituito all’ultimo momento

Richard Tucker che era morto. Poi ho

messo da parte Ernani e ho debuttato al

Metropolitan con il Rinuccio nel Gianni Schicchi.

Molto più tardi ho ripreso Ernani e lo canto ancora.

Ho cantato molte volte il Trovatore e molte volte Un ballo

in maschera. Ritengo, comunque, che Don Carlo e Luisa

Miller siano le due opere verdiane a me più congeniali.

In Italia sono stati paventati notevoli tagli ai finanziamenti per

la lirica. Cosa ne pensa e cosa la sua esperienza internazionale le

suggerisce in quest’ottica?

È una decisione infelice e miope, una grande delusione. La base della nostra civiltà è la cultura, la

musica, una cosa che sembra quasi inutile sottolineare in un Paese che ha una storia come l’Italia.

Dovranno maggiormente intervenire i privati con sponsorizzazioni e donazioni, in America funziona così.

Quali sono i teatri italiani in cui si trova meglio?

Ho cantato in molti teatri italiani e devo dire che mi

trovo benissimo dappertutto. Ma non nascondo – e

non lo dico per calcolo – che il mio ritorno alla Fenice,

dove prima dell’incendio ho cantato molto, mi rende

particolarmente felice. La distruzione della Fenice è stata terribile e tanto più grande è adesso per me la gioia

di vederla risorta.

Quali sono i suoi prossimi impegni e i progetti per il futuro?

Gli impegni più importanti sono, nel gennaio

2006 un Idomeneo in una nuova produzione della Staatsoper di Vienna, poi a luglio Manon Lescaut a Cagliari e a settembre l’inaugurazione del

Metropolitan. Nel 2007 sarò impegnato con la

Morte a Venezia di Britten per una nuova produzione a Vienna, poi Salisburgo in estate e in autunno una nuova produzione della Juive a Parigi.

Nel 2008 una nuova produzione del Metropolitan

con il Peter Grimes e ci sono dei progetti per un Benvenuto Cellini. Come vede, sto mettendo in repertorio

così tante opere nuove come mai in tutta la mia vita.

Devo studiare molto, ma le opere nuove sono

necessarie per non annoiarsi. Sono in carriera

da trent’anni ed è inimmaginabile continuare a cantare

soltanto La Bohème.

la Locandina

La juive (L’ebrea)

prima rappresentazione a Venezia in lingua originale opera

in cinque atti

libretto di Eugène Scribe

musica di Fromental Halévy

personaggi e interpreti principali

Éléazar Neil Shicoff / John Uhlenhopp

Jean-François de Brogni Roberto Scandiuzzi / Riccardo Zanellato

Léopold Bruce Sledge / Ricardo Bernal

Eudoxie Annick Massis

Rachel Susan Neves / Francesca Scaini

Ruggiero Vincent Le Texier / Vincenzo Taormina

Albert Massimiliano Velleggi

maestro concertatore e direttore Frédéric Chaslin

regia Günter Krämer

scene Gottfried Pilz

costumi Isabel Inez Glathar

Orchestra e Coro del Teatro La Fenice

direttore del Coro Emanuela Di Pietro

La juive (The Jewess)

text by Eugène Scribe

music by Fromental Halévy

Main characters and performers

Éléazar Neil Shicoff / John Uhlenhopp

Jean-François de Brogni Roberto Scandiuzzi / Riccardo Zanellato

Léopold Bruce Sledge / Ricardo Bernal

Eudoxie Annick Massis

Rachel Susan Neves / Francesca Scaini

Ruggiero Vincent Le Texier / Vincenzo Taormina

Albert Massimiliano Velleggi

conductor Frédéric Chaslin

director Günter Krämer

scenery Gottfried Pilz

costumes Isabel Inez Glathar

The Fenice Orchestra and Choir

Choir director Emanuela Di Pietro

13

Focus On

Il magico talento di Frédéric Chaslin

Direttore e pianista, un astro in costante ascesa

The enchanted talent of Frédéric Chaslin

Conductor and pianist, a star that won’t stop rising

F

rédéric Chaslin nasce a Parigi nel 1963. Dopo

aver studiato pianoforte e direzione d’orchestra,

comincia la sua carriera di direttore, sebbene continui a

esser per lui cosa gradita l’apparire anche come pianista

solista e accompagnatore.

La sua carriera lo vede iniziare affiancando Daniel Barenboim nella direzione dell’Orchestra di Parigi (1987

– 1989) e al Festival di Bayreuth (1988). Dal 1989 al

1991 è invece assistente di Pierre Boulez a Parigi con

l’Ensemble Intercontemporain. A Rouen viene nominato direttore d’orchestra della Opera and Symphony

Orchestra (1991-1994). Nel 1993 risiede come direttore

ospite al Bregenz Festival dove dirige Nabucco e Fidelio.

In Italia è al Teatro La Fenice di Venezia nel 1994 con

I racconti di Hoffmann di Jacques Offenbach e l’anno

successivo con La Sonnambula di Vincenzo Bellini. Dal

1997 viene regolarmente invitato come direttore ospite

alla Royal Scottish National Orchestra; dal ’99 al 2002

è direttore della Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra. Nel

febbraio dello stesso anno dirige Falstaff al Teatro Real

di Madrid, e molti concerti anche a Las Palmas, Valencia

e al Perelada Festival.

Poi ancora: La Favorita di Gaetano Donizetti all’Opera

di Roma, concerti al Teatro Regio di Torino, con l’orchestra di Arturo Toscanini e al Teatro Carlo Felice di

Genova.

Viene regolarmente invitato dall’Orchestra Filarmonica

di Israele, e recentemente è stato nominato direttore del

Teatro Nazionale di Mannheim. Dirige Tosca, La traviata, Romeo e Giulietta, Il barbiere di Siviglia con l’Opera di

Monaco e di Los Angeles.

Viene acclamato a Vienna per la sua direzione dei Puritani di Bellini, e nel 2004 vi ritorna con L’Elisir d’Amore

di Donizetti nelle vesti di direttore ospite. Durante la

stagione 2003/2004 dirige il Don Pasquale e il Faust a Berlino, mentre il Macerata Festival lo vede alla direzione

del Simon Boccanegra.

Nei progetti futuri, I Vespri Siciliani e I racconti di Hoffmann al Metropolitan e prestigiose collaborazioni con

l’Opera di Vienna e Monaco. (i.p.)

Nabucco, Bregenz Festival, 1993

14

Fidelio, Bregenz Festival, 1993

F

rédéric Chaslin was born in Paris in 1963. After his

general and musical studies (piano and conducting), he began his career as a conductor although he still enjoys appearing

as a pianist and piano accompanist.

He began his conducting career as Daniel Barenboim’s assistant at both the Orchestre de Paris (from 1987-89) and at the

Bayreuth Festival (1988). From 1989 to 1991 he was Pierre

Boulez’s assistant at the Ensemble Intercontemporain in Paris.

He was then appointed Musical Director of the Opera and

Symphony Orchestra in Rouen from 1991 to 1994.

Since 1993, Frédéric Chaslin has been permanent guest

conductor of the Bregenz Festival conducting Nabucco and

Fidelio there.

In Italy, he conducted in Venice’s Teatro La Fenice both The

Tales of Hoffmann in 1994, and Sonnambula in 1995. Since

1997, he has also been a regular guest conductor at the «Royal

Scottish National Orchestra». Frédéric Chaslin was chief conductor of the Jerusalem Symphony Orchestra from 1999 to 2002.

At Madrid’s Teatro Real, he conducted Falstaff in February

2002. He also conducted concerts in Las Palmas, Valencia

and at the Perelada Festival; then La Favorita at the Rome

Opera; concerts at the Teatro Regio in Torino, concerts with

the Arturo Toscanini Orchestra, concerts at the Teatro Carlo

Felice in Genova.

He is now regularly invited by the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra and he wasc recently named music director of Mannheim’s

National Theater. He conducted Tosca, La Traviata, Romeo e

Giulietta, Il Barbiere di Siviglia with Munich’s Bavarian State

Opera and the Los Angeles Opera.

After Chaslin’s acclaimed debut at the Vienna Opera with I

Puritani, he was appointed guest conductor there and returned

with L’Elisir d’Amore in 2004. In 2003/2004 season he

also conducted Don Pasquale and Faust at the Deutsche Oper

in Berlin and appeared at the Macerata Festival conducting

Simon Boccanegra.

Future plans include I vespri Siciliani and The Tales of

Hoffmann at the Metropolitan this autumn and further engagements with the Vienna State Opera and Bavarian State

Opera, Munich. (i.p.)

Focus On

Fenice, una stagione ricca e drammatica

«Rischiamo di perdere il nostro primato di grandi creatori d’opera»

Fenice, an intense and dramatic season

«We risk losing our primacy as the great creators of opera»

da una conversazione con / from a conversation with Sergio Segalini

O

I

l cartellone della Fenice anche quest’anno si rivela ricco e

variato, comprendendo, oltre all’opera d’esordio, La Juive di

Fromental Halévy, molti altri titoli importanti, a cominciare dal

Flauto magico e dal Lucio Silla di Mozart per proseguire

con La valchiria wagneriana e la Luisa Miller di Verdi. Ma

le difficoltà economiche delle Fondazioni musicali hanno spinto i

direttori artistici a ricorrere spesso a coproduzioni e collaborazioni

con istituzioni gemelle, magari straniere. A questo argomento già

accennava Sergio Segalini nel numero scorso di VeneziaMusica

e dintorni. Ora il direttore artistico della Fenice ci spiega più nel

dettaglio i seri problemi cui si trova di fronte chi come lui è chiamato a operare delle scelte nella programmazione.

La situazione generale di tutti i teatri lirici italiani è

drammatica. Porsi continuamente il problema del far

tornare i conti crea uno squilibrio alla direzione artistica:

siamo frenati nella nostra creatività. E credo che molti

non se ne rendano conto. L’Italia ha il dovere di mantenere alto il suo lato creativo. Non voglio dire con questo

che dovremmo fare solo nuove produzioni per tutta la

stagione, ma semplicemente che dovremmo avere un

margine di libertà maggiore. Come si fa ad andare avanti se il nostro Paese, che è per definizione la patria

del melodramma, non crea più? Come facciamo a

richiamare qui americani, inglesi, francesi, giapponesi, insomma tutti gli stranieri – e ce ne sono

tanti – che ogni anno accorrono a comprare i biglietti della Fenice se non proponiamo loro degli

spettacoli specificamente italiani? Di fronte alla

necessità di creare un solo nuovo allestimento ogni

anno, giunta come un monito da Roma, abbiamo

scelto Il crociato in Egitto di Giacomo Meyerbeer

con la regia e le scene di Pier Luigi Pizzi. Ma il

problema è che l’Italia non può proporre prodotti che vengono dalla Germania, dalla Francia,

dalla Svizzera, dall’Austria… Per esempio aveva-

nce again the theatre programme of the Fenice

is intense and varied, including not only its opening opera, La Juive by Fromental Halévy, but also many

other important titles, such as the Magic Flute and Lucio

Silla by Mozart, then Wagner’s Die Walküre and Verdi’s

Luisa Miller. However, the financial straits of musical

Foundations have frequently forced the artistic directors to resort to co-productions and collaboration with

twin institutions, some foreign. Sergio Segalini touched

this subject in the last number of VeneziaMusica e

dintorni. Now the artistic director of the Fenice will

go into the series of problems facing those who, like

himself, are responsible for deciding what is to be part

of the programme.

The general situation shared by all Italian opera houses is dramatic. Always being forced to face the problem of making the

figures balance creates an imbalance for the artistic management:

our creativity is restricted. And I believe that this is something

many people do not even realise. Italy has a duty to maintain its

creative quality. With this I am not trying to say we should only

offer new productions for the whole season, but that we should

simply have a greater margin of freedom. How can we go forward

if our country, which is by definition the very homeland of melodrama, can no longer create? How can we attract the Americans,

English, French, Japanese – all foreigners – and there are a great

many – who rush to buy tickets for the Fenice if we don’t offer

them specifically Italian performances? Faced with the necessity to

create just one new production each year – a warning from Rome

– we chose The Crusade in Egypt by Giacomo Meyerbeer,

with the set and production by Pier Luigi Pizzi. However, the

problem is that Italy cannot

offer products that come

from Germany,

from France,

Switzerland

or Austria…

15

Focus On

mo pensato a una nuova

scenografia per L’ebrea, ma

abbiamo dovuto rinunciarci

e affittare l’allestimento della

Staatsoper di Vienna, che

è bellissimo, per carità, ma

non è uno spettacolo nostro. Così perdiamo il nostro

primato, la nostra identità di

grandi creatori d’opera. Per

quattro secoli, dal Seicento

a oggi, noi italiani abbiamo

lavorato nel mondo della

musica, e siamo sempre stati

i primi. Adesso rischiamo di

diventare gli ultimi, abbiamo

una potenzialità creativa nettamente inferiore, per fare

degli esempi, a quella dei francesi o degli spagnoli, che

sono in pieno progresso, oltre che dei tedeschi con

Berlino, Monaco di Baviera, Colonia, Stoccarda, Francoforte… Ed è l’immagine del nostro paese che se ne

va. Perché l’Italia non è solo Leonardo, Caravaggio, il

Bernini e il Borromini: è anche e soprattutto musica. In

fin dei conti i grandi quadri italiani si possono ammirare anche alla National di Londra o al Metropolitan di

New York, oppure al Louvre. Al limite quel tipo d’arte

italiana si può visitare e godere da moltissime altre parti.

Ma la produzione operistica, che è sempre stata uno dei

nostri fiori all’occhiello, se si continua così presto verrà

meno. Ed è proprio un gran peccato.

Oltre a tutto questa perdita non riguarda soltanto il

mondo del teatro e della cultura. Colpisce da vicino

anche la gente. Se n’è già accorta ad esempio l’Arena di

Verona, che con i suoi ventimila posti faceva sempre il

tutto esaurito, e adesso non più. E non si parla di una

realtà marginale, la qualità

dell’Arena è molto alta, ma

anche lì si cominciano a pagare delle scelte di strategia

culturale poco lungimiranti.

Se infatti La Fenice si riempie è soprattutto grazie agli

stranieri, perché il pubblico

veneziano è scarso e in continua restrizione, perché prevalentemente composto da

persone anziane e da cittadini che spesso se ne vanno da

Venezia per i noti problemi.

Ad un certo punto, andando

avanti di questo passo, ci

ritroveremo anche senza gli

introiti dei biglietti, perché

come ho già detto il pubblico rischia di non venire più

qui, e di scegliere altre mete.

E oltre alle casse del teatro, a

risentirne ovviamente saranno i ristoranti, gli alberghi, i

negozi, e in definitiva la città

intera. Bisognerebbe riflettere anche su questo. (l.m.)

16

For example, we considered creating new scenography for The

Jewess, but we had to do without

and hire the one from the Vienna

Staatsoper, which is beautiful,

of course, but it is not our own.

Thus, we lose our primacy, our

identity as the great creators of

opera. For four centuries, from

the seventeenth century to today,

we Italians have worked in the

music world and we have always

been the leaders. Now we risk

becoming the last, we have a

creative potential that is clearly

inferior, compared for example, to

the French or Spanish, countries making the utmost progress, or

compared to the Germans with Berlin, Munich Bavaria, Cologne,

Stuttgart, or Frankfurt … It is the image of our country that

is disappearing. Italy is not just Leonardo, Caravaggio, Bernini

and Borromini - it is also and especially its music. When it comes

down to it, the great Italian paintings can also be admired in the

London National Gallery or at the New York Metropolitan

or at the Louvre. That sort of Italian art can also be seen and

enjoyed in countless other places. But if things continue in this

manner, opera production, which has always been one of our flagships, will soon falter. And it really is a great shame.

Furthermore, this loss does not just concern the world of theatre

and culture. It also has an immediate effect on the people. For

example, the Verona Arena with its twenty thousand seats has

already been affected – it used to be permanently sold out – now

that isn’t so. And it isn’t a case of a marginal situation – the

quality of the Arena is extremely high, but even there they are

beginning to pay the price of shortsighted cultural strategies. The

fact that La Fenice is full is mainly thanks to the foreigners,

because the Venetian audience is

scarce and constantly dropping

since the majority are elderly

people and inhabitants who often

leave the city because of the commonly known problems. If things

continue at this rate, at a certain

point we will find ourselves without the ticket takings because, as

I said before, the audience will no

longer come here, but will choose

other places instead. And apart

from the theatre ticket office, it is

clear that the restaurants, hotels,

shops and therefore the entire city

are affected. This needs to be reflected on, too. (l.m.)

La Valchiria di Richard Wagner,

a gennaio alla Fenice.

Die Walküre by Richard Wagner, at

La Fenice in January.

In alto/top: Die Walküre,

Adolph Mahnke, Königsberg 1942.

In basso/bottom: Lilli and Marie

Lehmann, Bayreuth 1876.

p. 15 a sinistra/on the left:

Die Walküre, Leo Pasetti, Munich 1921.

p. 15 a destra/on the right: Die Walküre,

Karl Emil Doepler, Bayreuth 1876.

Focus On

«I tagli faranno sparire metà stagione»

Il Sovrintendente Vianello sulle ripercussioni della Finanziaria

«The cuts will mean half the season disappears»

Superintendent Vianello talks about the Financial bill

L

a situazione non fiorente prospettata dal direttore musicale

della Fenice sembra rischiare di aggravarsi ulteriormente in

seguito ad alcune ancora non definitive decisioni politiche. Nel momento in cui chiude questo numero di VeneziaMusica e dintorni

infatti non è ancora stata approvata la manovra Finanziaria per

l’anno 2006, nel cui progetto il Fondo Unico per lo Spettacolo

verrebbe sensibilmente decurtato. In cifre nette, dai 464 milioni

di euro stanziati negli ultimi due anni (dopo un precedente taglio

del 9% rispetto al 2003) si passerebbe ai 300 previsti per il

2006, con una riduzione di 164 milioni. Al Fus attingono, in

percentuali diverse, tutte le attività che si riferiscono al mondo dello

spettacolo: cinema, teatro (di prosa), danza e musica. Una dichiarazione allarmata e telegrafica del Sovrintendente Giampaolo

Vianello chiarisce quali sarebbero le immediate ripercussioni di

questa riduzione dei fondi.

«Se il taglio sarà delle dimensioni prospettate ogni Fondazione dovrà fare il calcolo di cosa può fare e di cosa

non può fare. Decidere cioè che tagli apportare, perché

i soldi non li fabbrica nessuno, e il pubblico contribuisce

al massimo per il dieci per cento. In un bilancio come

quello della Fenice, che è di 32 milioni di euro, ne verrebbero a mancare 8. Se si calcola che i costi fissi del

personale ammontano a 19 milioni, il problema come

è intuitivo parte dagli stipendi e finisce alle produzioni.

Credo che tutti siamo amministratori della propria famiglia. Se si toglie il 25 % del contributo a istituzioni che

a fatica vanno in pareggio, queste fatalmente finiscono

per chiudere. C’è chi sarà costretto a farlo prima, chi

dopo, ma tutto si concretizzerà nell’arco di un anno. Se

il taglio verrà confermato bisognerà eliminare dal cartellone il 50 % della stagione, perché i soldi mancheranno

dal primo gennaio, non dalla stagione futura, ma da

quella del 2006, che è già stata organizzata.»

T

he deteriorating situation outlined by the musical

director of the Fenice risks getting even worse

following certain political decisions, which are not yet

final. While this number of VeneziaMusica e dintorni

is being published, the Financial package for the year

2006 has not yet been approved; in it, there would be

considerable cut backs for the project for the Unique

Fund for Performing Arts. In numbers, the 464 million

euro granted over the last two years (after a previous

cut of 9% compared to 2003), would be reduced to

the 300 foreseen for 2006, 164 million less. In different percentages, all the following activities are part of

the world of performing arts and draw from the UFP:

cinema, theatre (prose), dance and music. An alarmed

and telegraphic declaration from the Superintendent

Giampaolo Vianello explains what the immediate repercussions of these cuts in funding would be.

«If these cuts actually go through, each Foundation will have to

calculate what they can or can’t do. That means deciding what

cuts have to be made, because nobody manufactures money, and

the contribution from the audience is ten per cent at the most. A

budget such as that of the Fenice, which is 32 million euro, would

be reduced by 8. If one calculates that the fixed costs for staff

come to 19 million, the problem starts with the salaries and ends

with the productions. I think we are all acting as administrators

of our own family. If you take away 25% of the contribution

given to institutions that already have difficulties cutting even,

they obviously have to close. Some will be forced to do it sooner

than others but all in all it will take a year. If these cuts are approved, 50% of the season has to be eliminated from the theatre

programme, because as early as January first on, there won’t be

enough money, not for the next season, but for the one that has

already been organised for 2005-2006.»

Il Teatro

La Fenice.

17

Focus On

Il generoso gesto di Kitajenko

Il maestro ha rinunciato al cachet per protesta contro i tagli

The generous gesture by Kitajenko

The maestro foregoes his fee in protest against the cuts

L

a stagione sinfonica della Fenice è stata inaugurata

il 13 ottobre dal maestro Dimitrij Kitajenko, che

ha diretto l’Orchestra del risorto Teatro nella Settima

Sinfonia Leningrado di Šostakovič in occasione del primo centenario della nascita del compositore.

Evento oltremodo d’eccezione, vista la mirabile decisione del maestro Kitajenko: preso atto della difficile

situazione economica in cui versano le Fondazioni Liriche italiane a causa dei tagli ai finanziamenti pubblici,

in segno di protesta e solidarietà al mondo musicale ha

deciso di rinunciare integralmente al proprio cachet.

Facendosi portavoce di tutti i colleghi, il maestro ha

dichiarato che «anche gli artisti non si devono limitare

a denunciare la gravità della situazione, ma contribuire

alla soluzione del problema». I tagli ai finanziamenti,

come lo stesso sovrintendente della Fenice Giampoalo

Vianello ha spiegato, se confermati andranno a minacciare metà delle programmazioni in cartellone.

Arrivato in Italia, il maestro è venuto a conoscenza delle

enormi difficoltà che incontra la vita musicale e l’arte in

questo momento. «Non riesco a capire come un Governo possa decidere di non voler dare

i soldi necessari alla divulgazione della

cultura in un Paese come l’Italia, che ne

Dimitrij Kitajenko

rappresenta il centro europeo», ha detto sgomento Kitajenko. «La musica è il

cuore, l’anima, la salute di una nazione.

Molto facile distruggere una struttura

così fragile come la cultura, e molto

difficile ricostruirla. Tutti possono ricordare quanto fu terribile il rogo della

Fenice, e tutti possono anche ricordare

quanto tempo ci volle per restituirla al

fulgore. L’Italia è un simbolo in tutto il

mondo ed è veramente difficile accettare il fatto di non poter più far musica

come invece si dovrebbe».

È stato lo stesso Kitajenko a propendere per l’esecuzione della Settima Sinfonia, scritta a Leningrado e sua città natale. La composizione apre descrivendo

la vita normale, tranquilla e serena della

gente; dopo, poco a poco, cominciano

a sentirsi le voci delle forze distruttive,

delle forze nere che inesorabili stanno

arrivando a portare il loro scompiglio.

All’inizio sembra quasi un’orchestrina

di giocattoli, che poi cresce ad assumere dimensioni catastrofiche. «Questa

forza barbara vuole distruggere tutto il

mondo e tutte le cose positive, tutto ciò

che è stato costruito dalla civiltà. Questo primo tempo, molto lungo, finisce

18

T

he symphonic season of the Fenice was opened on October 13 by maestro Dimitrij Kitajenko, who conducted

the orchestra of the newly arisen Theatre with the Seventh

Symphony Leningrad by Shostakovich on the occasion of the

first centenary of the composer’s birth.

An exceptional event following the admirable decision of maestro Kitajenko: in view of the financial straits of the Italian

Opera Foundations resulting from cuts to public subsidies, he

forfeited the entire sum of his own performance fee completely

as a sign of protest and solidarity with the Italian music

world. Acting as spokesman for all his colleagues, the maestro

declared «artists must not limit themselves to denouncing the

gravity of the situation either, but must contribute to finding a

solution to the problem». As the superintendent of the Fenice,

Giampaolo Vianello himself explained, if the cuts to financing are confirmed, half the theatre programme is at risk.

When he arrived in Italy, the maestro immediately became

aware of the great difficulties facing the world of music and

culture in this period. «It is inconceivable how a Government

can decide not to give the money needed for the divulgation of

culture in a country such as Italy, the centre of European

Focus On

con voci di trombe e percussioni a significare: “uomini,

state attenti, perché tutto potrebbe tornare”. La seconda

parte è un intermezzo umoristico e scherzoso, il terzo

movimento propone un affresco della città di Leningrado, mentre il quarto passa dalla tragedia alla forza della

vittoria epica».

Šostakovič scrisse questa sinfonia nel settembre del

1941, quando Leningrado era sotto assedio e venne eseguita già nell’anno successivo in città, anche se mancava

gran parte degli orchestrali già morti. L’esito fu trionfale. «Quando la dirigo», ha spiegato il maestro, che con

Šostakovič ha avuto l’onore di lavorare, «sento di nuovo

la sua voce e spero che per l’Orchestra, per il Teatro, per

il pubblico e per me stesso, questa apertura della stagione sarà ricordata anche in futuro». (i.p.)

Dimitrij Šostakovič

culture», Kitajenko said in alarm. «Music is the heart, the

soul, the good health of a nation. It is easy to destroy a structure that is as fragile as culture, and it is extremely difficult

to rebuild. Everybody remembers how terrible the fire of the

Fenice was, and everybody remembers how long it took to rebuild. Italy is the symbol for culture throughout the world and

it is extremely difficult to accept the fact that one is unable to

make music as one should».

It was Kitajenko himself who proposed the performance of the

Seventh Symphony, written in Leningrad, his city of birth.

The composition begins with a description of the normal,

tranquil and serene life of the people; the voices of destructive forces gradually make themselves heard, the black force

that implacably arrives and causes widespread confusion. At

first it almost seems to be a small toy orchestra that gradually

grows until it takes on catastrophic dimensions. «This barbaric force wants to destroy the entire world and anything that

is positive, anything that was constructed by civilisation. The

first tempo, extremely long, ends with the voices of trombones

and percussion meaning: “men, be careful because everything

could come back”. The second part is a humorous and playful

intermezzo, the third movement offers a fresco of the city of

Leningrad while the fourth moves from tragedy to the force of

epic victory».

Šostakovič wrote this symphony in September 1941 when

Leningrad was under siege; it was performed in the city the following year, even though many of the musicians were already

dead. The result was triumphant. «When I conduct it», explained the maestro, who had the honour of working together

with Shostakovich, «I can hear his voice again and I hope that

for the Orchestra, the Theatre, the audience and for myself,

that this will be an opening to a season to be remembered in

the future, too». (i.p.)

19

Focus On

Teatro: sempre più impresa e meno cultura

Dalla riduzione del Fus all’assenza di mecenatismo

Theatre more as a business and with less culture

From the reduction of contributions to the lack of patrons

D

i fronte alla distruttiva riduzione del Fus (Fondo

Unico dello Spettacolo) si ripropone il problema

della sopravvivenza degli enti lirici. C’è chi sostiene che

la trasformazione dei nostri teatri in Fondazioni sia stata

positiva ai fini di una maggior funzionalità organizzativa

e di un sostegno economico. In realtà, ad uno sguardo

retrospettivo, in un decennio le Fondazioni non hanno

favorito agli enti lirici, anche perché in Italia, a differenza di quanto avviene negli Stati Uniti, non esiste una

cultura del mecenatismo, né la defiscalizzazione, sempre

richiesta, ma mai attuata (di fatto i maggiori contributi

«esterni» provengono dalle Fondazioni Cassa di Risparmio, mascherate da apporti privatistici).

La nuova legislazione voluta dall’allora Presidente del

Consiglio, Lamberto Dini, su suggerimento di Carlo

Fontana, sovrintendente della Scala (e successivamente

avallata dal Ministro alla cultura Walter Veltroni), ha

contribuito da un lato alla decapitazione della figura del

direttore artistico, ridotto al rango di un mero segretario artistico (il sovrintendente lo nomina e può sostituirlo in qualsiasi momento al di là persino degli impegni contrattuali), e

dall’altro all’eccessivo

potere, spesso molto

superiore all’apporto

finanziario, conferito

ai rappresentanti privati nel Consiglio di

amministrazione: basti

pensare ai rovinosi

interventi alla Scala

dei consiglieri legati

alle grandi imprese

milanesi.

In definitiva sarà bene

guardare non tanto agli

Stati Uniti, ma ai paesi

europei più avanzati

come la Germania,

ove i teatri sono sostenuti esclusivamente da

finanziamenti pubblici; essi svolgono una

significativa funzione

sociale anche per la

politica dei prezzi contenuti che consentono

alle nuove generazioni

e alle classi meno abbienti di frequentare

gli spettacoli.

In Italia ormai prevale

20

I

di / by Mario Messinis

n view of the destructive reduction of the Fus (Unique

fund for the performing arts), once again opera is faced

with the problem of survival. Some believe that the transformation of our theatres into Foundations was positive

since it allowed greater organisational functionality and

financial support. In reality, looking back, in a decade

the Foundations have not been of benefit to opera, also

due to the fact that in Italy, unlike in the United States,

there is neither a culture of patrons nor tax exemption,

which is always requested but never implemented. In fact the

greatest «external» contributions come from the Foundations

of the Cassa di Risparmio, disguised as private contributions.

The new legislation proposed by the former President of the Council, Lamberto Dini, following the

suggestion of Carlo Fontana, superintendent of

La Scala (and later backed by the Minister of Culture, Walter Veltroni), contributed on the one hand

to the diminution of the figure of the artistic director whose role was reduced to a mere artistic secretary (the superintendent can nominate and replace

him at any given moment, regardless of contract commitments), and

on the other, to excessive

power, which was often

much greater than the

financial support given

to the private representatives of the board of

directors - it suffices

to remember the ruinous interventions at La

Scala by the councillors

who were linked to big

Milanese businesses.

All in all, rather than

the United States, it

would be better to look

towards the more advanced European countries such as Germany,

where the theatres have

the exclusive support of

public financing; they

have an important social

function, also as regards

their policy of reasonable prices which allow

the new generations and

lesser well off classes to

go to performances.

Focus On

l’idea del teatro come impresa, in un’ottica commerciale

e di consumo che ne compromette il peso culturale.

Forse, dopo l’insuccesso delle Fondazioni liriche, si

dovrebbe proporre una nuova legge che garantisca un

adeguato finanziamento pubblico, riducendo però nel

contempo il peso di un sindacalismo selvaggio e onnipotente con l’eliminazione dei contratti integrativi, che

assecondano le velleità delle corporazioni. Sarà possibile rinnovare gli enti lirici con modalità presenti nei paesi

europei di più forte tradizione musicale? La questione è

aperta e di difficile soluzione: gli enti lirici sono costosissimi e necessiterebbero di un impegno adeguato da

parte dello Stato.

In Italy the idea of theatre as a business has now become prevalent – a commercial and consumerist point

of view that compromises its cultural importance.

Perhaps, in view of the failure of opera Foundations, a

new law should be proposed guaranteeing adequate public

financing, while reducing the weight of uncontrolled and

omnipotent trade unionism with the elimination of integrative contracts that favour the velleity of the corporations.

Will it be possible to renew opera following the models that

can be seen in European countries with a stronger musical tradition? The question is open and difficult to answer

– Opera is extremely expensive and requires adequate commitment from the State.

21