APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA

CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO

ANGELO BACCARELLA

p.

p.

2

3

TUTORIAL 1

p.

8

TUTORIAL 2

p. 10

TUTORIAL 3

INTRODUCTION

IPA – INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET

ENGLISH ALPHABET

PRONOUNS (PERSONAL, REFLEXIVE AND POSSESSIVE)

POSSESSIVE CASE

THE INDEFINITE PRONOUN & THE USES OF ONE

THE CONCEPT OF TIME

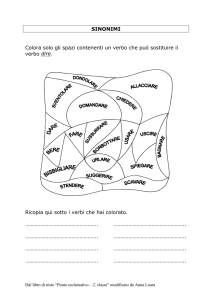

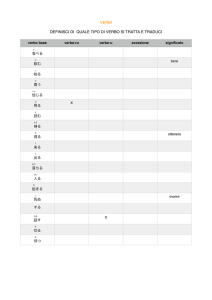

LIST OF ACTIVE VERBS

THE TENSE OF MODALS

SUBJECT AND PREDICATE

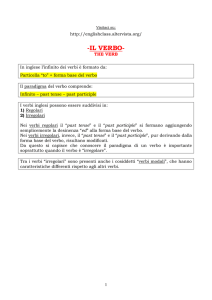

THE PRESENT

THE SIMPLE PRESENT TENSE

THE PRESENT PROGRESSIVE (PRESENT CONTINUOUS)

ADVERBS OF FREQUENCY (& POSITION)

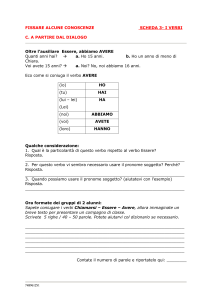

THE VERB TO BE

THE USE OF HAS/HAVE GOT

p. 18

TUTORIAL 4

THE NOMINAL PHRASE

NOUNS (COUNTABLE & UNCOUNTABLE; IRREGULAR PLURALS)

ARTICLES (ZERO ARTICLE / THE / A / AN)

DEMONSTRATIVES (THIS / THAT / THESE / THOSE)

QUANTIFIERS & EXPRESSIONS OF QUANTITY

POSSESSIVES (MY / YOUR / ECC)

QUANTIFIERS (NO / ENOUGH / MANY / MUCH / FEW / LITTLE / A LOT OF, ETC.)

PARTITIVES (SOME / ANY)

p. 24

TUTORIAL 5

p. 26

TUTORIAL 6

p. 31

TUTORIAL 7

p. 35

TUTORIAL 8

p. 42

p. 44

TUTORIAL 9

TUTORIAL 10

p.

p.

p.

p.

45

49

53

54

TUTORIAL 11

TUTORIAL 12

TUTORIAL 13

TUTORIAL 14

p. 59

TUTORIAL 15

p. 61

TUTORIAL 16

p. 63

TUTORIAL 17

OTHER DETERMINERS (ALL / HALF / BOTH / EITHER / NEITHER / GENERAL ORDINALS)

THE USE OF THERE IS/ARE

EXPRESSIONS OF PREFERENCE (USE OF THE VERBS LIKE & PREFER)

INTERROGATIVE ADJECTIVES AND PRONOUNS

INTERROGATIVE ADVERBS

TITLES & GREETINGS

ADJECTIVES (INCLUDING COMPARATIVES & SUPERLATIVES)

SYNTACTIC FUNCTION

ORDER OF ADJECTIVES

THE NOMINAL PHRASE

ADJECTIVES OF NATIONALITY

NUMBERS & DATES

TIME

THE PAST

ADVERBIALS IN RELATION TO THE PAST AND THE PRESENT PERFECT

THE SIMPLE PAST TENSE

THE PRESENT PERFECT TENSE

THE PAST PROGRESSIVE (PAST CONTINUOUS)

IRREGULAR VERBS

THE FUTURE

THE INFINITIVE

THE –ING FORM

PREPOSITIONS

SEMI-AUXILIARIES AND MODALS

THE PASSIVE VOICE

THE CLAUSE

PARTS OF SPEECH

SENTENCES (COORDINATION & SUBORDINATION)

RELATIVE PRONOUNS AND RELATIVE CLAUSES

RELATIVE ADVERBS

THE PRESENT PERFECT SIMPLE VS THE PRESENT PERFECT PROGRESSIVE

THE PAST PERFECT

THE PAST PERFECT PROGRESSIVE

THE CONDITIONAL

CONDITIONAL SENTENCES

SPECIAL USES OF WILL/WOULD AND SHOULD IN IF-CLAUSES

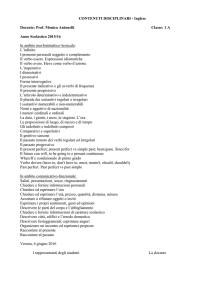

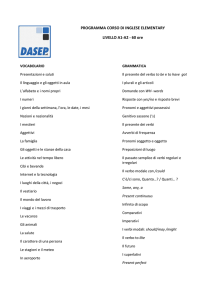

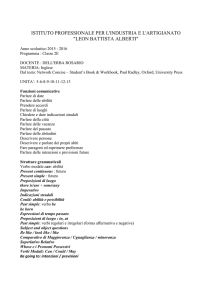

LINGUA INGLESE (Aprile - Giugno 2012)

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

2

INTRODUZIONE

Grammatica

Branca della linguistica che si occupa della struttura e della forma delle parole (morfologia1) così come della loro

combinazione per formare frasi (sintassi 2). Finalità della grammatica è lo studio del funzionamento del

linguaggio.

…

Il funzionamento di una lingua viene indagato dalla grammatica descrittiva, che appunto si occupa di ricercare e

descrivere nel modo più accurato possibile le relazioni fra i 'mattoni di costruzione' della lingua, cioè i morfemi,

che costituiscono le parole, e le loro combinazioni, che formano le frasi. Fa parte di questo settore anche la

descrizione di lingue o dialetti mai studiati in precedenza, o che non possiedono una forma scritta e dunque

vanno registrati direttamente dalla bocca di chi li parla. In generale i tipi di grammatica qui ricordati si occupano

della parte 'relazionale' del linguaggio, cioè di come questo si costruisce, di come si formano le parole e le frasi,

e di come i messaggi e le idee si trasmettono fra le persone.

Comunicazione

Fenomeno semiotico e sociale che consente di mettere in relazione due o più entità che si scambiano

informazioni. Secondo la definizione del linguista Roman Jakobson, la comunicazione è determinata da un certo

numero di 'fattori' che interagiscono: un emittente, un destinatario, un messaggio, un codice, un riferimento, un

contatto.

1 Morfologia

Nome dato a quella parte della grammatica che studia le forme delle parole. La morfologia

analizza le trasformazioni che può subire una parte del discorso, sia che si tratti di un verbo

che si coniuga ('abitare', 'io abito', 'io abiterò', 'io abitavo', 'io abitai', 'io abiterei') sia di un

nome che prende dei marchi di genere e di numero ('amico', 'amica', 'amici', 'amiche'). Anche

lo studio della derivazione, vale a dire il modo in cui si può creare una parola partendo da

un'altra parola ('abitare' > 'abitabile'; 'possibile' > 'impossibile') è di pertinenza della

morfologia.

Parte della grammatica che tratta dell'organizzazione delle parole in unità superiori e dei loro

rapporti reciproci.

2 Sintassi

Da: Microsoft ® Encarta ® 2007. © 1993-2006 Microsoft Corporation.

La teoria di Jackobson:

codificazione

EMITTENTE

Messaggio

(segni)

decodificazione

CODICE

DESTINATARIO

interpretazione

LA LINGUA INGLESE

Ogni parola, ogni frase, ogni struttura è un segno. Lo scopo di qualsiasi lingua è comunicare e, per comunicare, utilizziamo i

segni. La lingua inglese – come qualsiasi lingua – è un sistema di segni.

Il modo di pronunciare o scrivere una parola è la sua sostanza fisica, la forma del segno. Il contenuto della parola è il suo

significato. In linguistica si dice che la forma realizza il significato. I segni linguistici vengono interpretati: se si incontra una

parola che non si conosce, di solito, si cerca di indovinare – di dedurre – il suo significato, cioè di interpretare la parola. Se

si conosce la parola, allora la si interpreta in concordanza con le convenzioni della lingua. Il significato delle parole di una

lingua – e questo vale anche per le regole della grammatica – è il prodotto di convenzioni sociali. Se non si conosce una

lingua, è perché non si sanno alcune delle convenzioni – o non si conoscono affatto - della comunità nella quale la lingua è

parlata. L’insieme delle convenzioni costituisce il codice attraverso il quale viene veicolato il messaggio.

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

3

TUTORIAL 1

FONETICA

IPA – INTERNATIONAL PHONETIC ALPHABET

Consonants

/ /

bin

//

/ /

sing

//

/ /

call

//

/ /

pin

//

/ /

cheap

//

/ /

rose

//

/ /

day

//

/ /

small

//

/ /

far

/()/

/ /

shop

//

/ /

gas

//

/ /

television

//

/ /

joy

/ /

/ /

ten

//

/ /

hot

//

/ /

thin

//

/ /

yes

//

/ /

this

//

/ /

ball

//

/ /

video

//

/ /

must

//

/ /

wine

//

/ /

not

//

/ /

quiz

//

Vowels

Diphthongs

/ /

is

//

/ /

plain

//

/ /

happy

//

/ /

buy

//

/ /

beat

//

/ /

sound

//

/ /

head

//

/ /

boy

//

/ /

has

//

/ /

folk

//

/ /

bar

/()/

/ /

beer

/()/

/ /

dog

//

/ /

air

/()/

/ /

port

//

/ /

poor

/()/

/ /

book

//

/ /

boot

//

Symbols

/ /

but

//

//

Accento primario sulla sillaba che segue

/ /

about

//

//

Accento secondario sulla sillaba che segue

/ /

work

//

/ () /

Indica che la “r” finale viene pronunciata solo

davanti a parola che inizia con suono vocalico

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

4

Suoni vocalici

Fonemi

(segno fonetico)

descrizione del suono

esempi

trascrizione

fonetica

/ /

È simile alla i italiana ma si pronuncia più chiusa e con

suono molto breve

is

//

/ /

È molto simile alla i italiana ma con suono un po’ più

breve

happy

//

/ /

È simile alla i italiana ma si pronuncia più chiusa e con beat

suono molto lungo

//

/ /

È molto simile alla e aperta italiana

head

//

/ /

È molto simile alla e chiusa italiana ma con suono più

lungo

work

//

/ /

È un suono indistinto dato dal rilassamento della bocca

about

//

/ /

È simile alla a italiana ma più aperta, tendente al

suono della e chiusa italiana

has

//

/ /

È simile alla a italiana ma con suono più lungo

bar

/()/

/ /

È simile alla a italiana ma si pronuncia più chiusa e

con suono un po’ più breve

but

//

/ /

È molto simile alla o aperta italiana

dog

//

/ /

È molto simile alla o chiusa italiana ma con suono più port

lungo

//

/ /

È molto simile alla u italiana ma con suono più lungo

boot

//

/ /

È simile alla u italiana ma si pronuncia più chiusa e

con suono breve

book

//

La vocale e finale, dopo una consonante che segue la vocale i, ha la funzione di cambiare il suono

della i da /i/ o // in //:

bit

sit

pip

if

/bit/

/sit/

//

/ɪf/

bite

site

pipe

wife

/bt/

/st/

//

/waɪf/

(Eccezioni: i verbi GIVE e LIVE)

Ci sono molte parole che hanno diversi suoni a secondo del loro uso come parole intere o suffissi in parole

composte. La parola “composta” comporta uno spostamento del fiato sulla prima sillaba (o sillabe precedenti)

generando una variante debole del suono della vocale nel suffisso (quasi sempre la e indistinta /ə/):

variante forte

(strong form)

berry

land

man

men

shire

/‘beri/

/lænd/

/mæn/

/men/

/ʆaɪə/

variante debole

esempi

trascrizione fonetica

gooseberry

Scotland

gentleman

gentleman

Yorkshire

/ ‘gʊzbəri/ or / ‘gʊzbri/

/‘skətlənd/

/‘dʒentlmən/

/‘dʒentlmən/

/‘jɔkʆə/

(weak form)

/ -bəri/ or /-bri /

/-lənd/

/-mən/

/-mən/

/-ʆə/

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

5

Suoni consonantici

Non presente nella lingua italiana:

//

//

//

//

ha il suono leggermente nasale dato dalla fusione di n e g dura; corrisponde alla n

di manco (//)

Simile al suono sc di scena ma sonoro come nelle parole francesi rage, page

Suono sordo di t pronunciata con la lingua fra i denti, con una leggera aspirazione

Suono sordo di d pronunciata con la lingua fra i denti, con una leggera aspirazione

I suoni rappresentati con i simboli grafici delle consonanti seguenti corrispondono esattamente a quelli italiani:

grafemi

descrizione e suono

b

(In alcuni casi la b dell’ortografia non è pronunciata:

doubt, debt, thumb.)

f

m

n

p

(In alcuni casi la p dell’ortografia non è pronunciata:

receipt, psycohology, cupboard.)

v

fonemi

esempi

trascrizione

fonetica

to be

doubt

food

/ /

//

//

man

//

name

//

//

park

receipt

voice

//

//

//

//

desk

//

//

law

//

talk

//

toy

//

/()/

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

I seguenti segni grafici corrispondono a suoni simili ai suoni italiani:

d

l

t

È leggermente diverso dal suono corrispondente italiano:

il suono è matto, poco sonoro.

È simile al suono italiano, ma con la lingua tenuta più

indietro, vicino al palato.

(In alcuni casi la l dell’ortografia non è pronunciata:

walk, talk.)

È leggermente diverso dal suono italiano: il suono è

matto, più sordo del corrispondente italiano.

//

Le seguenti consonanti inglesi differiscono nel suono rispetto a quelle italiane:

c

1 Davanti alle vocali e, i, y, il suono corrisponde a s.

/ /

2 Davanti alle vocali a, o, u e in fine parola, il suono è

della c dura.

/ /

3 Il gruppo ch, seguita da vocale o in fine parola,

corrisponde al suono della c dolce.

/ /

4 Il gruppo ch, seguita da consonante e nelle parole di

origine greca o orientale, corrisponde al suono della c

dura.

5 Il gruppo ch corrisponde al suono di sc, come in scena,

nelle parole francesi o sentite come tali.

6 I gruppi -cce- e –cci- corrispondono al suono della c

dura seguita dalla s.

/ /

centre

city

cynic

cake

come

curry

act

chess

church

Christ

/ /

chemise

7 Il gruppo ck corrisponde al suono della c dura.

8 Il gruppo tch corrisponde al suono della c dolce.

/ / accent

accept

back

/ /

/ / match

//

//

//

//

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

6

grafemi

g

descrizione e suono

1 Ha suono duro (gh) davanti ad a, o, u e in fine parola.

2

3

4

5

6

fonemi esempi

game

go

gun

egg

gentleman

giraffe

get

girl

signature

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

/()/

sign

//

high

//

//

//

bridge

//

king

//

//

a) Davanti alle vocali e, i, ha suono dolce nelle parole

di origine latina;

//

b) Davanti alle vocali e, i, ha suono duro nelle parole di

origine germanica.

//

a) gn si pronuncia staccato quando le due lettere

appartengono a sillabe diverse (la g con il suono duro

e la n separata);

b) la g del gruppo gn è muta quando le due lettere

appartengono alla stessa sillaba.

Il gruppo gh finale di parola o seguito da t è muto,

tranne nel caso di poche parole nelle quali ha suono

della f.

Il gruppo dge ha il suono della g dolce.

Il gruppo ng ha il suono della n leggermente nasale e

della g dura appena percettibile.

trascrizione

fonetica

h

È aspirata (solo nelle seguenti parole e derivati è muta:

heir, honour, honest, hour).

//

help

//

j

Ha il suono della g dolce.

//

jeans

//

k

a) ha il suono della c dura;

//

key

//

knowledge

//

b) davanti a n è muta.

ph

Nella stessa sillaba è pronunciato f.

//

photo

//

qu

Ha il suono dalla c dura quasi sempre seguita dalla

semivocale //; soltanto in pochissime parole è seguita

da vocale.

//

question

//

//

red

radio

interface

//

//

//

fire

shire

assure

//

//

/()/

sister

/()/

space

//

to use

/ /

scene

science

system

Scotland

show

nation

mansion

assure

//

//

//

//

//

//

//

/()/

r

a) si pronuncia leggermente, non facendo vibrare la

lingua;

b) in posizione mediana, seguita da consonante, è muta

(si avverte la presenza della r dalla vocale pronunciata

più lunga del normale);

c) in posizione finale, seguita dalla vocale e, ha la

funzione di addolcire il suono vocalico complessivo

finale della parola trasformando il trittongo in dittongo o

monottongo (variazione allofonica);

d) r finale non è pronunciata, a meno che la parola che

segue non cominci per vocale.

s

1 a) generalmente ha suono sordo come in sole;

b) può avere suono sonoro come in rosa.

//

//

2 Il gruppo sc si pronuncia s quando è seguito da e, i, y; si

pronuncia / / negli altri casi.

3 Il gruppo sh, i gruppi –si- e –ti-, s/ ss seguite dalla

vocale u, si pronunciano tutti sc, come in scena.

//

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

7

grafemi

descrizione e suono

th

w

x

fonemi esempi

a) suono duro, come t pronunciata con la lingua tra i

denti (il suono è simile alla f italiana);

b) suono dolce, come d pronunciata con la lingua tra i

denti (il suono è simile alla v italiana).

1

a) è una semiconsonante in principio di parola e ha il

suono della vocale u di uomo, con l’accento sulla

vocale che segue;

b) è una semivocale in posizione mediana e finale e

suona come una u rapida.

2 Davanti a r è muta.

a) in principio di parola si pronuncia //

b) suono sordo

c) suono sonoro

y

z

a) è una semiconsonante in principio di parola e ha il

suono della vocale i di ieri, con l’accento sulla vocale

che segue;

b) è una semivocale in posizione mediana e finale e

suona come una i rapida.

Ha il suono della s dolce (in pochissime parole ha il

suono della g francese //).

trascrizione

fonetica

//

theatre

/()/

//

the

//

//

window

//

//

know

//

to write

/ /

xylophone

//

exercise

//

example

//

//

yellow

//

//

party

//

//

zoo

//

//

//

//

ENGLISH ALPHABET

A

B

C

D

E

F

G

H

I

J

K

L

M

N

O

P

Q

R

S

T

U

V

W

X

Y

Z

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ () /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

/ /

La conoscenza dell’alfabeto inglese è importante per lo spelling delle

parole.

Lo spelling può essere chiesto mediante le seguenti frasi:

What’s the spelling of …?

How do you spell …?

Esempi:

What’s the spelling of English?

(How do you spell English?)

E – N – G – L – I – S – H [ - - - - - - ]

Se in una parola si susseguono due lettere uguali, se ne pronuncerà

una sola preceduta da double:

How do you spell book?

(What’s the spelling of book?)

B – O – O – K [ - - ]

Introducing oneself:

Hello. My name is Angelo Baccarella.

How do you spell your surname?

B–A–C–C–A–R–E–L–L–A

[ - - - - () - - - ]

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

8

TUTORIAL 2

PERSONAL, REFLEXIVE, POSSESSIVE PRONOUNS

PERSONAL

PRONOUNS

SUBJECT OBJECT

CASE

CASE

I

me

you

you

he

him

she

her

it

it

we

us

you

you

they

them

1ST PERSON SINGULAR

2ND PERSON SINGULAR

MASCULINE

3RD

PERSON FEMININE

SINGULAR NON-PERSONAL

1ST PERSON PLURAL

2ND PERSON PLURAL

3RD PERSON PLURAL

3RD

PS

SINGULAR

INDEFINITE

(pronome impersonale)

REFLEXIVE

PRONOUNS

POSSESSIVE PRONOUNS

myself

yourself

himself

herself

itself

ourselves

yourselves

themselves

DETERMINER

FUNCTION

my

your

his

her

its

our

your

their

NOMINAL

FUNCTION

mine

yours

his

hers

ours

yours

theirs

oneself

one’s

-

–

one

one

PERSONAL PRONOUNS

La scelta del caso soggetto e del caso oggetto dipende dalla posizione grammaticale. La regola più semplice da

seguire è quella di utilizzare il caso soggetto prima del verbo che esprime l’azione di un soggetto e il caso oggetto

in tutte le altre posizioni:

SUBJECT CASE

I work / he loves / they are singing

(subject)

OBJECT CASE

I love her

Tom gave me a book

I sang to them

Tom came to me

(direct object)

(indirect object)

(prepositional

complement)

Sia il caso soggetto che il caso oggetto della prima e terza persona (tranne IT) possono essere complementi del verbo TO BE

nella forma comparativa e nell’inglese parlato e scritto informale, ma se il pronome è seguito da una proposizione, si preferisce la

forma del caso soggetto:

he’s older than I / me

it is I / me

it is I who teaches

IT generalmente viene utilizzato per le cose e per gli animali di cui non conosciamo il sesso:

the cat is under the table: it is watching the spider

IT viene utilizzato per le espressioni di tempo (senso cronologico), distanza, tempo (meteo) e temperatura:

it’s six o’clock

it’s 150 kms to Agrigento

it’s raining

it is cold today

Quando un infinito è il soggetto di una frase, normalmente si fa iniziare la frase con IT e si inserisce l’infinito successivamente:

it is easy to criticise

IT viene utilizzato come soggetto per verbi impersonali:

it seems …

it looks…

REFLEXIVE AND EMPHASISING PRONOUNS

I pronomi riflessivi vengono utilizzati come oggetti del verbo quando l’azione ritorna a chi /cosa la compie,

(soggetto e oggetto coincidono):

I hurt myself

John shaved himself

Quando ci sono diverse persone, il riflessivo è alla prima persona; se non è coinvolta la prima persona plurale allora il riflessivo è

alla seconda persona plurale:

You, John and I mustn’t deceive ourselves!

You and John mustn’t deceive yourselves!

I riflessivi vengono usati similmente dopo il verbo + la preposizione:

he spoke to himself

look after yourself!

I pronomi riflessivi hanno pure un uso enfatico; essi seguono una frase nominale o un altro pronome e rafforzano il loro significato:

I spoke to the teacher himself

Con lo stesso significato possiamo mettere il pronome riflessivo alla fine della frase:

Joan herself told me

=

Joan told me herself

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

9

POSSESSIVE PRONOUNS

I determinativi, o gli attributivi (chiamati anche aggettivi possessivi), nella lingua inglese si riferiscono (e si accordano in genere e

in numero) al possessore e non alla cosa posseduta:

Tom’s father is his father

Mary’s father is her father

a boy loves his mother

a girl loves her mother

Tutto ciò che è posseduto da un animale è indicato da ITS:

a tree drops its leaves in autumn

a dog licks its bone

Se è conosciuto il sesso, si può utilizzare HIS / HER.

Se c’è più di un possessore, umano e non, si utilizza THEIR:

the boys and girls love their mother

the trees drop their leaves

Gli aggettivi possessivi non variano se la cosa posseduta è singolare o plurale (si accordano con il possessore):

my book

my books

his hand

his hands

I nominali, chiamati anche pronomi possessivi, vengono utilizzati per svolgere la funzione di sostituire sia l’aggettivo possessivo

che il sostantivo:

this is my pen = this is mine

these are my pens = these are mine

that is your book = that is yours

these are your books = these are yours

L’espressione “OF MINE” ecc. significa “ONE OF MY” ecc.: a friend of mine

=

one of my friends

THE USES OF ONE

A) ONE NUMERICO Quando è usato con sostantivi numerabili al singolare indicanti sia persone che animali e cose, non è altro che

una forma enfatica dell’articolo non “definente” A(N): a / one month £1 = a / one pound

Nelle frasi dove si sta contando o misurando il tempo, la distanza, il peso ecc. A / AN e ONE sono intercambiabili ma non in altri

tipi di frasi in quanto ONE + sostantivo in genere significa “uno soltanto / non più di uno”:

an eagle is a bird one eagle is a bird (un’aquila è un uccello) (e le altre, cosa sono?)

a strong coffee is no good (un caffè forte non è buono)

(fa male alla salute)

one strong coffee is no good (

“

)

(necessitano più di una tazzina)

(THE) ONE viene usato come contrasto a THE OTHER nella costruzione correlativa:

one went this way, the other that way (uno andò di qua e l’altro di là)

ECCEZIONI: 1. ONE utilizzato con ANOTHER / OTHERS:

one (boy) wanted to read, another/others wanted to play

B) ONE DAY può essere utilizzato per indicare un futuro ipotetico: one day you’ll be rich!

ONE può essere utilizzato davanti a DAY / WEEK / MONTH / YEAR / SUMMER ecc. o davanti il nome del

giorno o del mese per indicare un tempo particolare quando qualcosa è successo:

one day a telegram arrived

one night there was a terrible storm

C) ONE SOSTITUTIVO Viene utilizzato come sostituto anaforico per sostantivi numerabili,

(la forma del singolare ONE; la forma del plurale ONES).

ONE SOSTITUTIVO prende i determinativi e gli aggettivi (ma raramente prende i possessivi o dimostrativi plurali):

‘Give me that pen’ ‘This one?’ / ‘Is this the one you mean?’

‘I’d like a drink, but a small one’ ‘Didn’t you prefer large ones?’

D) ONE IMPERSONALE Indica “la gente in generale” e traduce il pronome impersonale italiano “SI”; nel farne uso è implicito

l’inclusione del parlante; questo utilizzo è principalmente formale e spesso al posto di ONE si usa l’informale YOU:

one has to be patient you have to be patient.

E) ONE IMPERSONALE ha il genitivo ONE’S e il riflessivo ONESELF:

one doesn’t need to justify oneself to one’s friends

(non bisogna giustificarsi ai propri amici - agli amici di sé -)

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

10

TUTORIAL 3

THE CONCEPT OF TIME

PRESENT

PAST

◄

PAST TIME

(PRECEDING NOW)

◄

FUTURE

FUTURE TIME

(FOLLOWING NOW)

PRESENT TIME

(INCLUDING NOW)

►

►

VERBS

GENERAL

Il tempo è un concetto universale, non linguistico con tre dimensioni: passato, presente e futuro; con tense (tempo verbale)

si indica la corrispondenza tra la forma del verbo e il concetto di tempo. Aspect (il modo verbale) riguarda la maniera di

concepire l’azione verbale (per esempio: forma progressiva o tempo continuato), mentre mood rapporta l’azione verbale a

condizioni particolari come certezza, potere, dovere, volere, possibilità.

LIST OF ACTIVE VERBS

SIMPLE

COMPLEX

PROGRESSIVE

PRESENT

I write

(TO BE +

I am writing

PRESENT PROGRESSIVE

I was writing

PAST PROGRESSIVE

PERFECTIVE

PAST

VERB+ING)

(TO HAVE + PAST PARTICIPLE)

I have written

PRESENT PERFECT

I had written

PAST PERFECT

I wrote

PERFECT PROGRESSIVE

(TO HAVE + BEEN + VERB+ING)

I have been writing

PRESENT PERFECT PROGRESSIVE

I had been writing

PAST PERFECT PROGRESSIVE

FUTURE

SHALL / WILL + BASE FORM

BE GOING TO + BASE FORM

THE PRESENT PROGRESSIVE

THE SIMPLE PRESENT

SHALL/WILL + THE PROGRESSIVE

SHALL/WILL + THE PERFECT

I shall write tomorrow

I’m going to write a letter tomorrow

I’m writing a letter tomorrow

THE TENSE OF MODALS

PRESENT

can

may

shall

will / ’ll

must

ought to

need

dare

PAST

could

could (might)

should

would / ’d

(had to)

used to

dared

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

11

CONCEPT OF TIME

1

(NOW)

PAST TIME

FUTURE TIME

(PRECEDING NOW)

(FOLLOWING NOW)

PRESENT TIME

(INCLUDING NOW)

SIMPLE PRESENT

2

(NOW)

STATE PRESENT

…….…. ……….

HABITUAL PRESENT

TIMELESS

INSTANTANEOUS PRESENT

SIMPLE PAST

3

(THEN)

(NOW)

T2

T1

EVENT PAST

STATE PAST

HABITUAL PAST

CONCLUDED

….….

…….

T = TIME OF ORIENTATION

PROGRESSIVE ASPECT

PRESENT PROGRESSIVE

4

PAST

PRESENT

FUTURE

FUTURE

|____________ACTION____________|

BEGINNING

END

LIMITED

(NOW)

PAST PROGRESSIVE

PAST

PRESENT

|_________ACTION_______|

BEGINNING

END

(THEN)

(NOW)

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

12

PERFECTIVE ASPECT

PRESENT PERFECT

5

PAST

PRESENT

FUTURE

FUTURE

STATE MEANING

.

DURATION

………………..

(THEN)

EVENT MEANING

HABITUAL MEANING

(NOW)

PAST PERFECT

PAST

PRESENT

PAST STATE

.

EVENT

………..

HABIT

(THEN)

(NOW)

PERFECT PROGRESSIVE ASPECT

PRESENT PERFECT PROGRESSIVE

6

PAST

PRESENT

…|END

. …|END

..…………….. …|END

(THEN)

FUTURE

STATE MEANING

EVENT MEANING

HABITUAL MEANING

(NOW)

PAST PERFECT PROGRESSIVE

PAST

PRESENT

…|END

. …|END

……….. …|END

(THEN)

FUTURE

EVENT

HABIT

(NOW)

FUTURE

7

PAST

PREDICTION

INTENTION

STATE

PRESENT

(SHALL/ WILL)

(TO BE GOING TO)

PLAN – PROGRAMME

(PRESENT PROGRESSIVE)

FUTURE

ACTION

ACTION

ACTION

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

13

SUBJECT AND PREDICATE

Tradizionalmente c’è una distinzione basilare tra soggetto e predicato.

Il soggetto di una frase ha un rapporto molto ravvicinato con “ciò di cui si sta discutendo”, cioè il tema della frase, con l’implicazione che

qualche cosa (il predicato) viene detto di un “soggetto”. Un altro punto è che il soggetto determina l’accordo con il verbo, cioè con quelle

parti del verbo che richiedono una distinzione tra singolare e plurale. Inoltre è importante individuare il soggetto poiché è quella parte

del discorso che cambia posizione nella frase interrogativa.

Il predicato è un’unità più complessa. In inglese si può dividere in due parti costituenti: ausiliare, e la sua funzione di “operatore”, e

predication. Per quanto complessa possa essere la frase, il primo ausiliare è separato dal resto della frase. È a causa di questa funzione

sintattica che l’ausiliare si chiama operatore.

Questa divisione della frase è importante per capire la formazione dell’interrogativa e della negativa. I verbi ausiliari non hanno esistenza

indipendente (come verbi che esprimono un’azione) ma hanno la funzione di costituire, assieme al verbo che esprime l’azione, la frase

verbale. Il verbo TO DO è solo un “riempitivo” in certi processi di trasformazione della frase, mentre i verbi TO BE (essere) e TO HAVE

(avere) contribuiscono alla formazione del modo verbale; infine gli ausiliari modali (i verbi difettivi) contribuiscono alla formazione del

senso della modalità di intendere un’azione (esprimendo concetti come probabilità, possibilità, dovere ecc.)

Da notate che i verbi TO DO, TO BE e TO HAVE sono anche verbi lessicali, cioè esprimono fare (rendimento), essere e avere.

SENTENCE

SUBJECT

PREDICATE

AUXILIARY AND

OPERATOR

PREDICATION

1a

John

had

given Mary the book

1b

had

John

given Mary the book?

2a

she

is

reading the book

2b

is

she

reading the book?

3a

The book

can

be read by everyone

3b

can

the book

be read by everyone?

4a

he

-

4b

did

5a

5b

read the book

(simple past)

he

read the book?

(forma base)

The book

is

in English

is

the book

in English?

Nelle frasi negative il NOT della negazione segue l’operatore.

1c

John

had

not

(hadn’t)

given Mary the book

2c

she

is

not

(isn’t)

reading the book

3c

the book

can

not

(cannot)

be read by everyone

4c

he

did

not

(didn’t)

read the book

5c

the book

is

not

(isn’t)

in English

Quando una frase verbale non ha un verbo ausiliare (come in 4b e 4c) e nessuna parola che può fungere come operatore, è necessario

introdurre l’operatore riempitivo DO; nel caso degli esempi 4b e 4c, DO prende il segno del passato: DID.

Ci sono altre costruzioni in cui si richiede l’utilizzo di un operatore (e quindi dell’operatore riempitivo DO).

Queste sono:

FRASI ENFATICHE

Do be quiet!

I did enjoy that film!

TAG QUESTIONS

(vero? Non è vero?)

John read the book, didn’t he?

RISPOSTE BREVI

Yes, I do

No, I don’t

FRASI INTERROGATIVE CON WH- (nelle quali l’elemento WH- non è soggetto)

When did John read the book?

Who did he give the book to?

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

14

THE PRESENT

Dobbiamo distinguere tre tipi di presente:

A) TIMELESS (senza tempo):

B) LIMITED (determinata nel tempo):

C) INSTANTANEOUS (istantanea):

che si esprime con il simple present;

che si esprime con il present progressive;

che si esprime o con la forma semplice (specialmente in una

serie) o con la forma progressiva.

THE SIMPLE PRESENT TENSE

I’m hungry / I love you / the sun rises in the east

dramatic narrative / formal declarations / sports commentaries / etc.

he works in London (every day)

PRESENT STATE

PRESENT EVENT

PRESENT ‘HABIT’

THE PRESENT PROGRESSIVE

It’s raining!

I’m walking to work while my car is being repaired.

TEMPORARY PRESENT

TEMPORARY ‘HABIT’

THE SIMPLE PRESENT TENSE

FORMAZIONE il Simple Present ha la stessa forma dell’infinito senza il TO (forma Base). Alla terza

persona singolare si aggiunge una –s –.

infinitive:

Affirmative

I work

you work

he / she / it works

we work

you work

they work

TO WORK

Negative

I do not work

you do not work

he / she / it does not work

we do not work

you do not work

they do not work

(base form: WORK)

Interrogative

do I work?

do you work?

does he / she / it work?

do we work?

do you work?

do they work?

Negative interrogative

do I not work?

do you not work?

does he / she / it not work?

do we not work?

do you not work?

do they not work?

Siccome i tempi semplici non hanno verbi ausiliari, essi non hanno parole che possono servire come

operatori per formare le forme negative, interrogative e interrogative-negative. Per questo motivo

dobbiamo introdurre l’ausiliare riempitivo DO.

DO si accorda con il soggetto e quindi prende la – s – della terza persona singolare;

DO è seguito dalla forma base del verbo.

DO è generalmente contratta nella forma negativa e interrogativa-negativa.

I don’t work

he doesn’t work

don’t I work?

doesn’t he work?

ATTENZIONE:

Il verbo TO BE – essere – non segue la regola del presente semplice. Si trasforma in forma negativa

aggiungendo “not” direttamente al verbo, mentre l’interrogativo si forma invertendo il soggetto con il

verbo.

NOTE ORTOGRAFICHE

I kiss

I fish

I watch

I box

I do

he / she / it kisses

he / she / it fishes

he / she / it watches

he / she / it boxes

he / she / it does

I carry

he / she / it carries

I verbi che finiscono in –SS, –SH, –CH, –X e –O

aggiugono –ES invece di –S

I verbi che finiscono in –Y, che segue una consonante

preceduta da una sola vocale, cambiano la –Y in –I

e poi aggiungono –ES

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

15

THE PRESENT PROGRESSIVE (PRESENT CONTINUOUS)

FORMAZIONE

Il presente progressivo si forma con l’ausiliare del verbo TO BE (essere) al tempo

presente e con il participio presente / gerundio (forma base + il suffisso –ING)

Affirmative

I am working

You are working

He / she / it is working

We are working

You are working

They are working

Negative

I am not working

you are not working

he is not working

we are not working

you are not working

they are not working

Interrogative

am I working?

are you working?

is he working?

are we working?

are you working?

are they working?

Negative interrogative

Am I not working?

Are you not working?

Is he not working?

Are we not working?

Are you not working?

Are they not working?

Soggetto e ausiliare / ausiliare e negazione generalmente vengono contratti

I’m working

you’re working

He’s working

I’m not working

you aren’t working

he isn’t working

aren’t I working?*

aren’t you working?

isn’t he working?

*notare la forma irregolare per: AM I NOT.

NOTE ORTOGRAFICHE

quando un verbo finisce in una sola –E, questa –E cade prima di aggiungere –ING:

love, loving

write, writing

(questo non succede quando i verbi finiscono in -EE, -YE, -OE, -GE:

see, seeing dye, dyeing

hoe, hoeing

singe, singeing)

quando un verbo monosillabico finisce con una sola consonante preceduta da una sola vocale, la

consonante raddoppia prima di aggiungere –ING (tranne –X):

stop, stopping

run, running

i verbi di due o più sillabe in cui l’ultima sillaba c’è una sola consonante preceduta da una sola vocale,

la consonante raddoppia prima di aggiungere –ING se l’accento cade sull’ultima sillaba:

begin, beginning

prefer, preferring

(enter, entering: l’accento non è sull’ultima sillaba)

-L, -M, -P finali vengono sempre raddoppiate:

travel, travelling

worship, worshipping

program, programming

signal, signalling

i verbi basi in –IE, sostituiscono il –IE con –Y prima di aggiungere –ING:

die, dying

lie, lying

I VERBI CHE ACCETTANO O NON ACCETTANO LA FORMA PROGRESSIVA

I verbi che accettano l’aspetto progressivo sono i verbi che denotino attività: (WALK, READ,

DRINK, WRITE, WORK, ecc.) o processi (IMPROVE, GROW, WIDEN, , ecc.).

I verbi che indicano eventi momentanei (KNOCK, JUMP, NOD, KICK, ecc.), se usati con il

progressivo indicano ripetizione:

he kicked (un movimento della gamba)

he was kicking (movimenti ripetuti della gamba)

I verbi di stato non accettano la forma progressiva (perché non possono accettare il concetto di

un’azione che si svolge in un tempo determinato).

I verbi che non accettano la forma progressiva sono:

i verbi della percezione: FEEL, HEAR, SEE, SMELL, TASTE (anche SOUND e LOOK quando

indicano SEMBRARE);

i verbi che si riferiscono a emozioni o stati emotivi: BELIEVE, ADORE, DESIRE, DETEST, DISLIKE,

DOUBT, FORGET, HATE, HOPE, IMAGINE, KNOW, LIKE, LOVE, MEAN, PREFER, REMEMBER,

SUPPOSE, UNDERSTAND, WANT, ecc. (anche i verbi SEEM e APPEAR);

i verbi che si riferiscono ad un rapporto o stato: BE, BELONG TO, CONCERN, CONSIST OF,

CONTAIN, COST, DEPEND ON, DESERVE, EQUAL, FIT, HAVE, INVOLVE, MATTER, OWE, OWN,

POSSESS, REQUIRE, ecc.

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

16

TO BE

ESSERE

AFFIRMATIVE

NEGATIVE

INTERROGATIVE

I am

I am not

am I?

you are

you are not

are you?

he / she / it is

he is not

is he?

we are

we are not

are we?

you are

you are not

are you?

they are

they are not

are they?

Soggetto e ausiliare / ausiliare e negazione generalmente vengono contratti

I’m

I’m not

you’re

you aren’t

he’s

he isn’t

NEGATIVE INTERROGATIVE

am I not?

are you not?

is he not?

are we not?

are you not?

are they not?

aren’t I?*

aren’t you?

isn’t he?

*notare la forma irregolare per: AM I NOT.

HAVE & HAVE GOT

AVERE

Per esprimere possesso (AVERE) vengono utilizzati due verbi nella lingua inglese: TO HAVE e TO HAVE GOT. Il secondo

viene usato prevalentemente nella lingua parlata con registro colloquiale; la forma scritta e la forma parlata “corretta” e

formale, invece, preferiscono l’uso di TO HAVE.

TO HAVE

AFFIRMATIVE

NEGATIVE

INTERROGATIVE

NEGATIVE INTERROGATIVE

I have

I do not have

do I have?

do I not have?

you have

you do not have

do you have?

do you not have?

he has

he does not have

does he have?

does he not have?

we have

we do not have

do we have?

do we not have?

you have

you do not have

do you have?

do you not have?

they have

they do not have

do they have?

do they not have?

DO NOT e DOES NOT sono normalmente alla forma contratta nella frase negativa e interrogativa-negativa

I don’t have

don’t I have?

you don’t have

don’t you have?

he doesn’t have

doesn’t he have?

TO HAVE GOT

AFFIRMATIVE

NEGATIVE

INTERROGATIVE

NEGATIVE INTERROGATIVE

I have got

I have not got

have I got?

have I not got?

you have got

you have not got

have you got?

have you not got?

he has got

he has not got

has he got?

has he not got?

we have got

we have not got

have we got?

have we not got?

you have got

you have not got

have you got?

have you not got?

they have got

they have not got

have they got?

have they not got?

Generalmente si utilizza la forma contratta del HAVE NOT e HAS NOT sono normalmente alla forma contratta nella frase

soggetto con l’ausiliare

negativa e interrogativa-negativa

I’ve got

I haven’t got

haven’t I got?

you’ve got

you haven’t got

haven’t you got?

he’s got

he hasn’t got

hasn’t he got?

Esempio:

Jack has a beautiful house.

Jack has got a beautiful house.

Attenzione!

Soltanto la forma con HAVE viene utilizzata quando si parla di azioni.

Esempio:

I usually have breakfast at 8 o'clock.

Non è possible I usually have got breakfast at 8 o'clock.

La forma interrogativa di HAVE segue la regola per il present simple:

Esempio:

Do you have a fast car?

Non è possible. Have you a fast car?

HAVE e HAVE GOT sono utilizzati solo al presente. Per il passato o il futuro va utilizzato HAVE.

Esempio:

She had a copy of that book. (past simple) She will have a copy of that book. (future)

Non è utilizzata la forma contratta con HAVE alla forma affermativa.

La forma contratta è utilizzata con HAVE GOT.

Esempio:

I have a red bicycle. / I've got a red bicycle.

Non è possibile I've a red bicycle.

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

17

ADVERBS OF FREQUENCY

100%

TRADUZIONE ITALIANA

AVVERBI DI FREQUENZA COMUNI

sempre

always

MENO COMUNI

//

nearly always

constantly

normally

generally

di solito

usually

//

frequentemente

frequently

//

spesso

often

sometimes

occasionally

//

//

//

rarely

seldom

//

//

habitually

continuously

regularly

repeatedly

50%

qualche volta

ogni tanto

sporadically

di rado

raramente

infrequently

quasi mai

mai

0%

hardly ever

never

/ ()/

/()/

ever

/()/

(con verbo italiano negativo)

mai

(con verbo italiano affermativo)

Ever in italiano corrisponde a “mai” e viene utilizzato nelle frasi in cui non compaiono altri tipi di negazioni.

Never invece viene tradotto letteralmente come “ non… mai” e si usa nelle frasi in cui vi è già presente un’altra

forma di negazione.

La loro posizione:

1. Se la proposizione ha un solo verbo (cioè, non ha ausiliare), l’avverbio va posto tra il soggetto e il verbo:

Position A

subject

adverb

verb

predicate

Pasquale

usually

goes

to work by car.

2. Eccezione. Il verbo essere (TO BE) richiede l’avverbio dopo il verbo:

Position B

subject

verb

adverb

predicate

Pasquale

Concetta

is

isn’t

often

usually

late.

late.

3. Se la proposizione ha un verbo composto (ausiliare / operatore + verbo), l’avverbio va posto tra l’ausiliare / operatore e il

verbo che esprime l’azione:

Position C

subject

aux / operator

adverb

main verb

predicate

I

Maria

The students

can

doesn’t

have

never

usually

sometimes

remember

smoke.

forgotten

his name.

to do their homework.

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

18

TUTORIAL 4

NOUNS

Ci sono quattro tipi di sostantivi (nomi) nella Un sostantivo può svolgere la funzione di:

lingua inglese:

Soggetto di un verbo:

Jack kissed Jill;

comuni: dog, chair, man;

Complemento dei verbi BE, BECOME, SEEM:

propri: John, Italy, London, Mr Smith;

Joseph is a teacher;

astratti: beauty, fear, charity;

Oggetto di un verbo:

Jill kissed Jack;

collettivi: team, group, swarm.

Oggetto di una preposizione: I spoke to Joseph;

Caso possessivo (genitivo sassone): Dante’s works.

GENERE

maschile: ragazzi, uomini, animali maschili;

femminile: ragazze, donne, animali femminili;

neutro: cose inanimate, animali inferiori di cui non conosciamo il sesso.

ECCEZIONI:

Navi, auto, nazioni

femminile;

Alcuni sostantivi hanno la stessa forma sia per il maschile sia per il femminile:

parent, painter, driver, singer, cousin, child, artist, judge, rider, etc.;

Forme diverse:

brother-sister, uncle-aunt, lord-lady, bull-cow, horse-mare, nephewniece;

Alcuni sostantivi formano il femminile dal maschile aggiungendo il suffisso -ESS. Da notare che i sostantivi

che terminano in -OR o -ER spesso lasciano cadere -O o -E:

actor-actress, conductor-conductress (ma manager-manageress).

FORMAZIONE DEL PLURALI In genere, i sostantivi formano il plurale aggiungendo una -S:

boy, boys

girl, girls

dog, dogs

day, days

ECCEZIONI:

I sostantivi terminanti in -O o -SS, -SH, -CH, -S o -X formano il plurale aggiungendo -ES:

tomato, tomatoes

hero, heroes

kiss, kisses

brush, brushes

church, churches

gas, gasses

box, boxes

ma le parole di origine straniera terminanti in -O aggiungono soltanto -S:

piano, pianos

photo, photos

folio, folios

cameo, cameos

I sostantivi terminanti in –Y preceduta da consonante, trasformano la -Y in -I e poi aggiungono -ES:

baby, babies

lady, ladies

country, countries

c) Dodici sostantivi terminanti in -F o -FE lasciano cadere -F o -FE e aggiungono -VES:

calf (vitello), calves

elf (elfo), elves

half (metà), halves

knife (coltello), knives

leaf (foglia), leaves

loaf (pane /pagnotta), loaves

self (stesso), selves

sheaf (mannello), sheaves

shelf (mensola), shelves

thief (ladro), thieves

wife (moglie), wives

wolf (lupo), wolves

ma 1) scarfs (sciarpa) o scarves

2) per tutti gli altri casi si aggiunge una –S: cliffs,

safes,

chiefs

Alcuni sostantivi formano il plurale mediante un cambiamento vocalico:

(uomo)

(uomini)

man

men

//

//

(donna)

(donne)

woman

women

//

//

(piede)

(piedi)

foot

feet

//

//

(dente)

(denti)

tooth

teeth

//

//

(topo)

(topi)

mouse

mice

//

//

(pidocchio)

(pidocchi)

louse

lice

//

//

(oca)

(oche)

goose

geese

//

//

(bue)

(buoi)

ox

oxen

//

//

(fanciullo)

(fanciulli)

ma child

children

//

//

I sostantivi presi dal latino o dal greco e rimasti invariati formano il plurale seconde le regole del latino

o del greco:

basis

(base)

bases

//

//

crisis

(crisi)

crises

//

//

thesis

(tesi)

theses

//

//

phenomenon

(fenomeno)

phenomena

/f/

/f/

formula

(formula)

formulae

//

//

hypothesis

(ipotesi)

hypotheses

//

//

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

19

DETERMINERS

I determinativi sono delle parole che specificano il raggio di riferimento di un sostantivo in diversi

modi: rendendo il sostantivo definito (the boy), indefinito (a boy) o indicando la quantità (many boys).

Per capire il ruolo grammaticale dei determinativi dobbiamo considerare quali determinativi e quali

sostantivi possono stare assieme. Ci sono tre classi di sostantivi comuni che sono fondamentali per la

scelta dei determinativi: i sostantivi numerabili singolari, i sostantivi numerabili plurali e i sostantivi non

numerabili.

I determinativi precedono sempre il sostantivo che determinano ma hanno delle posizioni diverse

rispetto alla classe / categoria di appartenenza. La categoria più importante è quella dei determinativi

centrali, inclusi gli articoli; questa può essere preceduta dalla categoria dei predeterminativi e/o seguiti

dalla categoria dei post-determinativi.

PREDETERMINERS

CENTRAL DETERMINERS

POSTDETERMINERS

all, both, half.

Articoli: the, a(n)

double, twice, three times, Dimostrativi: this, that, these, those.

ecc.

Possessivi: my, your, his, her, its, our, your, their

one-third, ecc.

e genitivi.

what, such, ecc.

Distributivi e quantitativi (quantifiers): some, any,

no, every, each, either, neither, enough, much.

Determinativi in Wh-: what(ever), which(ever),

whoever, whose.

Numeri cardinali: one, two, three, ecc.

Numeri ordinali: first, second, third, ecc.

Ordinali generali: next, last, other, ecc.

Quantifiers: many, few, little, several,

more, less, ecc.

I determinativi centrali formano sei gruppi relativi alla loro presenza con le classi dei sostantivi: i

sostantivi numerabili singolari (bottle - bottiglia), i sostantivi numerabili plurali (bottles – bottiglie) e i

sostantivi non numerabili (water – acqua). Il segno di spunta ( ) nei riquadri che seguono indica quali

classi di sostantivi possono stare assieme alla classe dei determinativi in esame.

COUNTABLE

SINGULAR

bottle

PLURAL

bottles

UNCOUNTABLE

the

no

a

Attenzione: l’utilizzo di un determinativo

esclude l’utilizzo di un altro, di qualsiasi

gruppo esso sia.

water

d

these

those

e

a(n)

every

each

either

neither

f

much

Possessives:

1° ps. sing.

1° ps. plu.

2° ps. sing.

2° ps. plu.

our

your

3° ps. plu.

their

3° ps.

3° ps.

3° ps.

my

your

sing. m. his

sing. f. her

sing. n. Its

zero article (assenza dell’articolo

come nella frase: I need water)

b

partitivi: some (frasi affermative)

any (frasi neg. e interr.)

enough

this

that

c

a

b

c

d

e

f

=

=

=

=

=

=

Senso specifico: riferimento preciso.

Senso generico: riferimento globale o parziale ma mai particolare.

Senso specifico: riferimento preciso ( dimostrativi singolari ).

Senso specifico: riferimento preciso ( dimostrativi plurali).

Senso generico: riferimento all’individualità, alla classe, ecc. ma mai specifico.

Senso generico: riferimento quantitativo di abbondanza in un contesto specifico.

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

20

I predeterminativi precedono i determinativi centrali. Ci sono quattro classi di predeterminativi:

all

both

half

I predeterminativi all, both, half vanno davanti agli articoli, ai possessivi o ai dimostrativi. Essendo

“quantificatori” (quantifiers) non possono precedere i determinativi che denotano quantità: every, either,

each, some, any, no, enough. (half precede sempre un determinativo.)

I post determinativi seguono qualsiasi determinativo centrale ma precedono aggettivi. In questa classe ci

sono i numeri ordinali, cardinali e diversi “quantificatori”.

a) A parte one, che si trova solo con i sostantivi numerabili singolari, tutti i numeri cardinali (two,

three, ecc.) si trovano solo con i sostantivi numerabili plurali.

b) I numeri ordinali si trovano solo con i sostantivi numerabili e generalmente precedono qualsiasi

numero cardinale nella frase nominale.

c) Gli ordinali generali (next, last, other, further, etc.) possono o precedere o seguire i numeri

ordinali.

d) Quantifiers

many

few

a few

fewer

several

much

little

a little

molti/e

pochi/e

un po’

molto/a

poco/a

un po’

meno

parecchi/e

a little bit of

un poco di

informale

Il determinativo comparativo MORE si trova solo con i sostantivi numerabili plurali e sostantivi non

numerabili, e il determinativo comparativo LESS di solito solo con i sostantivi non numerabili:

Some more tea, please.

Questi possono seguire altri post determinativi:

We need two more chairs.

Ci sono altri tipi di frasi che indicano quantità: alcuni possono trovarsi sia con sostantivi numerabili

che con sostantivi non numerabili:

plenty of

tutti con il significato di

bottles.

molto/a, molti/e

I have

a lot of (informale)

water.

lots of (molto informale)

Alcuni esempi di costruzioni utilizzando i determinativi:

Uncountable nouns

water

the water

my water

no water

enough water

this water

that water

some water

much water

all the water

half the water

much water / a lot of water

little water

a little water

all this water

plenty of water

Countable nouns

Singular

Plural

the bottle

a bottle

my bottle

no bottle

this bottle

that bottle

every bottle

each bottle

either bottle

neither bottle

half a bottle

all the bottle

the first bottle

the second bottle

bottles

the bottles

my bottles

no bottles

some bottles

enough bottles

these bottle

those bottles

all my bottles

all the bottles

both bottles

all my many bottles

few bottles

a few bottles

many bottles / a lot of bottles

several bottles

plenty of bottles

both my two bottles

both the first two bottles

all the twenty bottles

the next three bottles

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

21

THE INDEFINITE ARTICLE

ARTICLES

L’articolo “non definente”, corrispondente all’articolo indeterminativo italiano, è A o An.

Si mette la forma A davanti a parola che inizia per consonante o a vocale con suono consonantico (le semivocali W e

Y in principio di parola; la vocale U pronunciata /…/; i grafemi EU- e EW- pronunciate /…/; l’O iniziale di one e di once

pronunciate /…/ ).

a man

a table

a woman

a youth

a university

a useful thing

a European

such a one

La forma AN si mette davanti a parola che inizia per vocale o per H muta*:

an elephant

an apple

an hour

an honourable man

Non ha genere:

a man

a woman

an animal

a table

* [le sole parole nella lingua inglese che iniziano con h muta sono heir (erede), honest (onest), honour (onore), hour (ora) e derivati di queste]

Uso di A e AN:

Davanti a un sostantivo numerabile al singolare quando viene menzionato per la prima volta e non rappresenta nessuna

persona o cosa in particolare:

I need a holiday (ho bisogno di una vacanza)

I received a letter (ho ricevuto una lettera)

Davanti a un sostantivo numerabile al singolare per indicare un esempio a campione di una classe di cose (in italiano viene

usato l’articolo determinativo con il significato di qualunque / qualsiasi): a child needs love

tutti i bambini hanno bisogno di amore = qualunque / qualsiasi bambino ha bisogno di amore

Nel predicato sostantivale (il complemento nominale in inglese); davanti al sostantivo, al singolare, che segue i verbi

copulativi. Sono inclusi anche i mestieri e le professioni:

he became a politician (divenne un politico)

she is a teacher (è un insegnante)

In certi espressioni numeriche:

a couple (un paio) a half (una metà)

a dozen (una dozzina) an eighth (un ottavo)

a quarter (un quarto)

a hundred (un centinaio)

a million (un milione)

In espressioni di prezzo, velocità, misura, percentuale ecc.:

a kilo (un chilo) four times a day (quattro volta al giorno)

sixty kilometres an hour (60 kilometri all’ora)

Con few e little: a few = un piccolo numero (con sostantivi numerabili plurali)

a little = una piccola quantità (con sostantivi non numerabili)

In esclamazioni davanti a sostantivi concreti e numerabili al singolare:

What a hot day! (che giornata calda!)

What a pretty girl! (che bella ragazza!)

A si può mettere davanti a Mr/Mrs/Miss + cognome per indicare che la persona è sconosciuta al parlante:

a Mr Smith (un certo Sig. Smith)

L’articolo “non definente” non si usa nei seguenti casi:

Davanti a sostantivi numerabili plurali.

Non c’è una forma plurale quindi il purale di a dog è dogs.

Davanti a sostantivi non numerabili. I seguenti sostanti sono non numerabili in inglese:

advice (consiglio)

information (informazione) news (notizia)

furniture (mobilio)

e vengono spesso preceduti da some, any, a little, a piece of, a lot of ecc.

Knowledge (conoscenza) viene considerato non numerabile tranne quando viene usato in un senso particolare

prende l’articolo:

a knowledge of languages is always useful

e allora

Hair (capigliatura) viene considerato non numerabile tranne quando si indica ogni pelo separatamente, allora

numerabile: ‘a hair’, ‘two hairs’ ecc.

diventa

Experience col significato di “pratica nel fare (qualcosa)” non è numerabile ma

“qualcosa che succede a qualcuno” è numerabile.

an experience col significato di

Davanti a sostantivi astratti: beauty, fear, hope, death ecc. tranne quando vengono usati in un senso particolare:

some children suffer from a fear of the dark (alcuni bambini soffrono di una paura del buio)

Davanti i nomi di pasti tranne quando sono preceduti da un aggettivo:

we had a good breakfast (abbiamo fatto/mangiato una buona colazione)

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

22

THE DEFINITE ARTICLE

ARTICLES

L’articolo “definente”, corrispondente a tutti gli articoli determinativi italiani, è THE.

THE non ha genere e non ha numero: the boy, the boys

the girl, the girls

the day, the days

L’articolo viene usato:

A)

Davanti a sostantivi che esprimono il senso di unicità o che vengono considerati come unici:

the earth

the sea

the sky

the North Pole

Davanti a un sostantivo che diventa specifico (nel contesto specifico) in quanto menzionato una seconda volta:

I received a letter; in the letter there was an invoice. (ho ricevuto una lettera; nella lettera c’era una fattura)

Davanti a sostantivo che diventa specifico attraverso l’aggiunta di una frase o proposizione:

the student that I met (… che ho incontrato) the place where I met him (il luogo dove…)

Davanti a sostantivo che a causa della località può rappresentare soltanto una cosa:

Ann is in the garden (il giardino di questa casa)

Please pass me the wine (il vino sul tavolo)

Davanti a superlativi, numeri ordinali e only, utilizzati come aggettivi o pronomi:

Mount Blanc is the highest mountain in Europe

B)

THE + sostantivo singolare può rappresentare una classe di animali o di cose:

the whale is in danger of becoming extinct (la balena rischia di diventare estinta)

MAN può essere utilizzato per rappresentare la razza umana ma non ha articolo.

THE + sostantivo al singolare vuole il verbo al singolare e i pronomi soggetto da utilizzare sono HE, SHE, IT:

if man destroys other species, he may be next on the list

(se l’uomo distrugge altri animali, egli potrebbe essere il prossimo sulla lista)

C)

THE + aggettivo rapresenta una classe / categoria di persone:

the old = gli anziani in generale

the poor = i poveri in generale

Il verbo è al plurale e il pronome soggetto è THEY: the young are impatient; they want changes

D)

THE viene usato davanti ai nomi propri di mari e di fiumi, gruppi di isole, catene di montagne, nomi plurali di nazioni e ai

deserti:

the Atlantic the Arctic

the Alps

the USA the Netherlands the Sahara

THE viene usato davanti a nomi che consistono di sostantivo + OF + sostantivo:

the Straits of Dover the Gulf of Mexico the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

THE viene usato davanti a nomi che consistono di aggettivo + sostantivo

(ma l’aggettivo non deve essere un punto cardinale: east, west ecc.): the Gold Coast the Ivory Coast

E)

Davanti a sostantivi di strumenti musicali:

the piano

the guitar

the flute

F)

THE viene usato davanti a sostantivi di pasti se questi sono specificati da una proposizione:

the dinners that I had in England were great (le cene che ho fatto /mangiato in Inghilterra erano fantastiche)

L’articolo “definente” THE non si usa nei seguenti casi:

Davanti ai nomi di luoghi (tranne le eccezioni viste sopra); davanti ai nomi propri di persone.

ECCEZIONE: THE + cognome al plurale indica la famiglia: ‘the ... family’: The Smiths = Mr and Mrs Smith (and

children).

Davanti a sostantivi astratti, tranne quando questi vengono usati in un senso particolare:

Men fear death (l’uomo ha paura della morte)

Dopo un sostantivo nel genitivo sassone, o dopo un aggettivo possessivo:

the boy’s uncle = the uncle of the boy (lo zio del ragazzo)

it is my book = the book is mine (è il mio libro = il libro è (il) mio)

Davanti a nomi di pasti (tranne che questi sono qualificati da una proposizione):

The Scots have porridge for breakfast (gli scozzesi mangiano porridge per colazione)

Davanti a parti del corpo e capi di abbigliamento in quanto questi preferiscono l’aggettivo possessivo (il pronome possessivo

con funzione determinativa):

Raise your right hand. (alza la mano destra) He took off his coat. (si tolse il cappotto)

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

23

ESPRIMERE APPREZZAMENTO E PREFERENZA

TO LIKE / TO PREFER

Il verbo To Like significa Piacere e, in italiano, viene tradotto alla forma riflessiva:

I like chocolate = mi piace il cioccolato

I like films = mi piacciono i film

Formazione:

AFFIRMATIVE

NEGATIVE

INTERROGATIVE

NEGATIVE INTERROGATIVE

I like

I do not like

do I like?

do I not like?

you like

you do not like

do you like?

do you not like?

he likes

he does not like

does he like?

does he not like?

we like

we do not like

do we like?

do we not like?

you like

you do not like

do you like?

do you not like?

they like

they do not like

do they like?

do they not like?

DO NOT e DOES NOT sono normalmente alla forma contratta nella frase negativa e interrogativa-negativa

I don’t like

don’t I like?

you don’t like

don’t you like?

he doesn’t like

doesn’t he like?

Utilizziamo il verbo To Like con

a) sostantivi numerabili al plurale:

I like cars

b) sostantivi non numerabili:

I like music

c) con sostantivi verbali (il gerundio):

I like eating good food

in quanto verbo che esprime apprezzamento, ha come sinonimo il verbo To love (amare):

I love cars

I love music

I love eating good food

Il verbo TO PREFER (preferire), invece, è utilizzato per esprimere preferenza

Formazione:

AFFIRMATIVE

NEGATIVE

INTERROGATIVE

NEGATIVE INTERROGATIVE

I prefer

I do not prefer

do I prefer?

do I not prefer?

you prefer

you do not prefer

do you prefer?

do you not prefer?

he prefers

he does not prefer

does he prefer?

does he not prefer?

we prefer

we do not prefer

do we prefer?

do we not prefer?

you prefer

you do not prefer

do you prefer?

do you not prefer?

they prefer

they do not prefer

do they prefer?

do they not prefer?

DO NOT e DOES NOT sono normalmente alla forma contratta nella frase negativa e interrogativa-negativa

I don’t prefer

don’t I prefer?

you don’t prefer

don’t you prefer?

he doesn’t prefer

doesn’t he prefer?

Utilizziamo il verbo To Prefer con

a) sostantivi numerabili al plurale:

I prefer cars

b) sostantivi non numerabili:

I prefer music

c) con sostantivi verbali (il gerundio):

I prefer eating good food

di solito il verbo To Prefer contrasta qualcosa o un’attività con qualcos’altro o un’altra attività:

I prefer cars to bicycles

I prefer rock music to classical music

I prefer eating Italian food to British food.

(Quando il secondo elemento di paragone è noto, si può omettere: I prefer eating Italian food)

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

24

TUTORIAL 5

INTERROGATIVE ADJECTIVES AND PRONOUNS

PER LE PERSONE

SOGGETTO

OGGETTO

POSSESSIVO

WHO (CHI)

WHOM, WHO (CHI)

WHOSE (DI CHI)

(PRONOME)

(PRONOME)

(PRONOME E AGGETTIVO)

PER LE COSE

SOGGETTO

OGGETTO

WHAT (CHE COSA / QUALE)

WHAT (CHE COSA / QUALE)

(PRONOME E AGGETTIVO)

(PRONOME E AGGETTIVO

WHICH (QUALE …)

WHICH (QUALE …)

(PRONOME E AGGETTIVO)

(PRONOME E AGGETTIVO)

PER LE PERSONE E COSE

QUANDO LA SCELTA

LIMITATA

SOGGETTO

È OGGETTO

Hanno la stessa forma sia per il singolare che per il plurale.

WHAT (Adj.) può essere usato anche per le persone.

WHO, WHOSE + sostantivo, WHAT, WHICH utilizzati come soggetti di una proposizione, normalmente sono seguiti da un

verbo affermativo, non negativo:

Who pays the bills? Ann pays them.

Whose is this? It’s mine (whose book is this?)

Which of your sisters is getting married? Jane is.

in altre parole, quando si desidera sapere chi compie / ha compiuto / compierà un’azione, si utilizza WHO? WHOSE?

WHICH? con un verbo alla forma affermativa.

WHAT? può essere usato in un modo simile:

What happened?

Esempi:

WHO

WHO / WHOM

come soggetto

come oggetto

WHOSE

WHAT

WHAT

WHICH

(possessivo)

come soggetto

come oggetto

come soggetto

WHICH

come oggetto

ATTENZIONE: nelle

Who is this student?

Who took my book?

Who / Whom did you see? I saw the student.

Who did you speak to? / To whom did you speak?

Whose book is this? (adj.) It’s Ann’s (book). Whose is this? (pron.)

What killed him? (pron.) The exams killed him!

What paper do you read? (adj.) I read ‘The Times’.

Which of them passed the exam? (verbo affermativo)

Which of them is the eldest? (pron.) Mary is the eldest.

Which did you appreciate most? (pron.) The students that passed the exam.

Which university did you go to? (adj.) I went to Palermo.

frasi dove l’elemento WH- non è soggetto bisogna costruire la frase in forma interrogativa.

WHO / WHOM in quanto oggetti diretti:

Whom did you meet? Formale

Who did you meet? Informale

La preposizione è seguita da WHOM:

With whom did you go?

With whom were you speaking?

Nell’inglese parlato la preposizione viene spostata alla fine della frase. Quando ciò avviene WHOM diventa WHO:

Who did you go with?

Who were you speaking with?

WHAT, aggettivo e pronome, è un interrogativo generale utilizzato per le cose. Quando si utilizza WHAT con la

preposizione, questa viene normalmente posizionata alla fine della frase:

What did you kill them with?

I killed them with the exams!

WHAT + BE ... LIKE? è un’espressione che viene utilizzata sia per le persone sia le cose come richiesta di una descrizione:

What was the exam like?

What was the weather like?

Usata per le persone può indicare l’aspetto fisico o il carattere: What is she like? She’s pretty. She’s stupid.

WHAT DOES HE / SHE / IT LOOK LIKE? riguarda solo l’aspetto fisico: What does he look like? He’s tall.

WHAT IS HE / SHE? = what is his / her profession (Cosa fa? Qual’è la sua professione? Che lavoro svolge?):

He’s a student. She’s a teacher.

WHAT (adj.) è molto comune nelle domande / richieste di misurazioni. Viene utilizzato principalmente con i sostantivi:

age (età), size (misura), weight (peso), length (lunghezza), breadth (larghezza), width (ampiezza), height

(altezza), depth (profondità):

What age is she?

What height / length / size is your room?

Da notare che viene utilizzato sempre il

verbo TO BE (essere).

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

25

INTERROGATIVE ADVERBS

Questi sono: WHY, WHEN, WHERE, HOW

WHY? Significa “per quale ragione” / “perché” e richiede BECAUSE nella risposta:

Why didn’t he pass the exam? Because he didn’t study.

WHEN? Significa “in quale tempo”, “quando”:

When do you get up? At 7 a.m.

WHERE? Significa “in quale luogo”, “dove”:

Where do you live?

HOW? Significa “in che modo”, “come”:

How did you come to lectures?

In Palermo.

By car.

HOW può essere utilizzato:

con aggettivi, come alternativa a WHAT seguito da sostantivo:

How old is he?

(che età ha?)

How deep is the water? (quanto è profonda l’acqua?)

con MUCH e MANY:

How much do you want? (quanto vuoi?)

How many books did you buy? (quanti libri hai comprato?)

con avverbi:

How fast does she drive? (a che velocità guida?) Much too fast.

How often do you see him? (“quanto spesso…?”)

How early do you get up? (“quanto presto…?”)

Da notare che HOW IS HE / SHE? È una richiesta sulla salute. Da non confondere HOW ARE YOU? (“come stai / state?“)

con HOW DO YOU DO? (“piacere della conoscenza“): il secondo è un saluto, non una domanda.

TITLES & GREETINGS

SIGNORE

SIGNORA

SIGNORINA

SINGOLARE

Mr Rossi

(col nome)

Sir

Gentleman

Mrs Rossi

Madam

Lady

Miss Rossi

(2^ pers. Vocativo)

(3^ pers.)

(col nome)

(2^ pers. Vocativo)

(3^ pers.)

(col nome)

Madam

Young lady

(2^ pers. Vocativo)

(3^ pers.)

PLURALE

Mr Rossi and Mr Bianchi

Messrs Rossi & Bianchi

Gentlemen, Sirs

Gentlemen

Mrs Rossi and Mrs Bianchi

Ladies

Ladies

Miss Rossi and Miss Bianchi

The Missis Rossi & Bianchi

Ladies

Young ladies

Signora e signorina neutro

Ms (col nome) sing.

Ladies

plu.

How do you do? – piacere di conoscerla.

Pleased to meet you – piacere di conoscerla.

Very pleased to make your acquaintaince – molto lieto di conoscerla, di far la sua conoscenza

Pleased to have met you – piacere di averla conosciuta (al momento di separarsi)

Pleased to have made your acquaintance –

Infomale

“

“

Hello, hi – ciao, salve

Goodbye, bye, bye-bye, see you ciao, arrivederci (al momento di separarsi)

Formale, cortese

Good morning / day / afternoon / evening / night

buon giorno / pomeriggio, buona serata / notte.

APPUNTI DI GRAMMATICA - CENTRO LINGUISTICO DI ATENEO - ANGELO BACCARELLA

26

TUTORIAL 6

ADJECTIVES

a) I principali tipi di aggettivi sono:

1)

2)

3)

qualificativi: square, good, bad, heavy, clever, fat;

dimostrativi: this, that, these, those;

distributivi: each, every, either, neither;

4)

5)

6)

quantitativi: some, any, no, few, many, much, one, twenty;

interrogativi: which, what, whose;

possessivi: my, your, his, her, its, our, your, their.

b) Accordo

Nella lingua inglese gli aggettivi hanno soltanto una forma sia con i sostantivi maschili e femminili, sia con i sostantivi

singolari e plurali; cioè, non hanno né genere né numero:

a good boy (un ragazzo bravo)

good boys (ragazzi bravi)

eccezione: i dimostrativi (THIS /THAT: singolari; THESE / THOSE: plurali)

Gli aggettivi normalmente precedono il sostantivo (posizione attributiva): a big city a red car an interesting book

Quando ci sono due o più aggettivi prima di un sostantivo questi non vengono separati dalle congiunzioni AND/ OR / BUT

tranne quando gli ultimi (i più vicini al sostantivo) sono aggettivi di colore: a big square box,

a tall young man

ma

a black and white hat,

a green, white and red flag

Gli aggettivi qualificativi possono seguire i verbi copulativi BE (essere), SEEM (sembrare), APPEAR (sembrare,

fisicamente), LOOK (sembrare / apparire) e quindi avere posizione predicativa; in questo caso una congiunzione separa gli

aggettivi se questi sono due o più di due:

the weather was cold, wet and windy

La maggior parte degli aggettivi possono essere sia attributivi ( pre-modificatori di sostantivi) che predicativi (complimenti di

verbi).

(vedere struttura proposizione SVC:

(S) English grammar

(V) is

(C) complex)