Prima parte lezioni “interazioni geni e ambiente epigenetica”

Durante lo sviluppo, l’esperienza gioca un ruolo

determinante nel guidare l’emergere del

comportamento in maniera individuo specifica all’interno

di un trend maturativo comune alla specie.

La presenza di un determinato background genetico

costituisce la situazione al contorno in cui l’esperienza

opera.

Costituisce, ovvero, la base della formazione dei circuiti

neurali sulla cui maturazione l’esperienza agisce per

guidare l’emergenza del comportamento

Patrimonio genetico = potenzialità

ma anche vincolo, limite

per l’azione dell’esperienza

E’ sempre più evidente che fattori genetici e fattori

ambientali non sono indipendenti tra loro nel controllare

lo sviluppo del sistema nervoso e del comportamento;

ciò che è importante è l’interazione tra essi.

Donald Hebb riassunse molto efficacemente

questa idea rispondendo a un giornalista che gli

chiedeva chi, tra geni e ambiente, contribuisse

maggiormente alla personalità. Hebb rispose

domandando al giornalista se per l’area di un rettangolo

fosse più importante la base o l’altezza.

Studi che esaminano nell’uomo le interazioni

geni-ambiente nella probabilità di sviluppare

disturbi del comportamento o del tono

dell’umore

Approcci allo studio del ruolo di fattori genetici nel

comportamento e nei suoi disturbi

La storia recente della ricerca sul ruolo di fattori genetici nello sviluppo del

comportamento e nei suoi disturbi ha seguito tre grandi approcci, ciascuno con la sua

logica e le sue assunzioni.

Il primo approccio assume che vi sia una relazione diretta fra geni e

comportamento.

In particolare, assume che i geni causino i disturbi

del comportamento.

Lo scopo di questo approccio è stato di correlare la presenza di disturbi nel

comportamento con differenze individuali nella sequenza del DNA. “This has been

attempted using both linkage analysis and association analysis, with regard to many

psychiatric conditions such as depression, schizophrenia and addiction. Although a few

genes have accumulated replicated evidence of association with disorder, replication

failures are routine and overall progress has been slow.” (Caspi et al., 2006)

“Because of inconsistent findings, many scientists have despaired of the search for a

straightforward association between genotype and diagnosis, that is, for direct main

effects.” (Caspi et al., 2006).

Caspi et al. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7, 583–590 (July 2006) | doi:10.1038/nrn1925

Il secondo approccio ha cercato di aggirare questo scoglio

cercando correlazioni fra il genotipo individuale e fenotipi

intermedi, chiamati endofenotipi.

“Endophenotypes are heritable neurophysiological, biochemical,

endocrinological, neuroanatomical or neuropsychological

constituents of disorders (es. from ASDs).” (Caspi et al., 2006)

Si assume che gli endofenotipi abbiano cause genetiche più

semplici rispetto al fenotipo completo. Quindi, l’assunzione dietro

questo approccio è che è più semplice identificare i geni associati

con endofenotipi che identificare i geni associati con il disturbo

con cui tali endofenotipi sono correlati.

Anche questo approccio, però, cerca un effetto principale di fattori

genetici nelle differenze interindividuali.

Caspi et al. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7, 583–590 (July 2006) | doi:10.1038/nrn1925

Il terzo e più nuovo approccio cerca di incorporare nello studio delle

differenze interindividuali nel comportamento l’effetto dell’ambiente.

Questo approccio, detto approccio “interazioni geni-ambiente” differisce in

maniera forte dai due approcci precedenti, che cercano un “effetto principale”

dei fattori genetici.

“Main-effect approaches assume that genes cause disorder, an

assumption carried forward from early work that identified single-gene

causes of rare Mendelian conditions. “ (Caspi eta l., 2006).

L’approccio “interazioni geni-ambiente” (Gene x Environment, G x E) invece

assume che patogeni ambientali possano causare disturi del comportamento e

che il genotipo influenzi la suscettibilità a tali patogeni.

Si assume quindi che i geni siano fattori di rischio per la suscettibilità a

patogeni ambientali.

In contrasto con gli studi che cercano effetti principali del genotipo, secondo

l’approccio G xE non c’è attesa per una associazione diretta genecomportamento in assenza di patogeni ambientali (e viceversa).

Caspi et al. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7, 583–590 (July 2006) | doi:10.1038/nrn1925

L’approccio G x E è scaturito da due tipi di

osservazioni:

1. Disturbi del comportamento e del tono

dell’umore hanno cause legate all’ambiente ed

all’esperienza individuale;

2. C’è eterogeneità nella risposta a “patogeni”

ambientali (resilienza/vulnerabilità)

“Like other non-communicable diseases that have common prevalence

in the population and complex multi-factorial aetiology, most mental

disorders have known non-genetic, environmental risk factors (that

is, predictors whose causal status is unproven).

Environmental risk factors for mental disorders discovered to date

include (but are not limited to):

maternal stress during pregnancy, maternal substance abuse during

pregnancy, low birth weight, birth complications, deprivation of normal

parental care during infancy,

childhood physical maltreatment, childhood neglect, premature parental

loss, exposure to family conflict and violence,

stressful life events involving loss or threat,

substance abuse, toxic exposures”

Caspi et al., 2006

I patogeni ambientali sono quindi in realtà non “causali”, ma

sono fattori di rischio. L’esposizione ad essi non sempre

causa un disturbo del comportamento.

Sia gli studi nell’uomo che gli studi in modelli animali hanno

consistentemente mostrato una grande variabilità

interindividuale nelle risposte comportamentali a patogeni

ambientali.

“Heterogeneity of response characterizes all known environmental

risk factors for psychopathology, including even the most

overwhelming of traumas.

Such response heterogeneity is associated with pre-existing

individual differences in temperament, personality, cognition and

autonomic physiology, all of which are known to be under genetic

influence.” (Caspi et al., 2006).

“The hypothesis of genetic moderation implies

that differences between individuals,

originating in the DNA sequence, bring about

differences between individuals in their

resilience or vulnerability to the environmental

causes of many pathological conditions of the

mind and body.”

Caspi et al., 2006

Esempi di interazioni geni x ambiente:

Sovraespressione del gene NMDA2B x ambiente arricchito,

(memoria migliore per animali wild type, ceiling effect per animali

con mutazione)

G x E nella suscettibilità a sviluppare dipendenza da sostanze:

Esempio: Cabib et al., 2000

Uso di linee di topi “Inbred”, largamente usati per la genetica del

comportamento.

Prima di entrare nel vivo dell’argomento, vi introduco il sistema

endogeno della ricompensa

Qui andare al file sistema endogeno della ricompensa

Saline

Drug of abuse

appaiato

Place preference

non appaiato

C57B6J

DBA

C57B6J

DBA

Conditioned place preference test, due background genetici diversi. C57, più

suscettibili a sviluppare dipendenza da sostanze d’abuso dei DBA

Descrizione del “conditioned Place Preference “test

Place preference

C57

unpaired

paired

Place preference

Un periodo moderato di carenza di cibo (“food shortage”), che

costituisce una esperienza “ecologica” e piuttosto comune in

natura, può invertire o cancellare le differenze fra le linee C57

e DBA nella risposta comportamentale alla esposizione a

psicostimolanti. Quindi, una “sfida” ambientale può annullare la

differenza fra i genotipi.

Neuromodulatory system lesion

Ambiente normale

Food shortage

DBA

Fin qui 27 ottobre

unpaired

paired

“The period of food shortage occurred when the

animals were mature and was terminated before

the administration of amphetamine.

Strain differences in behavior appear highly

dependent on environmental experiences.

Consequently, to identify biological

determinants of behavior, in this case

resilience to addiction, an integrated

approach considering the interaction between

environmental and genetic factors needs to

be used.”

Cabib et al., 2000

Ventura et al., 2003

Trasformare i C57 in DBA modificando la

trasmissione cortico striatale

La corteccia prefrontale esercita un forte effetto

modulatorio sui meccanismi di dipendenza.

La trasmissione noradrenergica nella corteccia

prefrontale mediale (mpFC) modula ad esempio l’effetto

della anfetamina a livello del comportamento.

Il lavoro di Ventura et al mira a verificare che l’azione

modulatoria della noradrenaline (NE) a livello

prefrontale sia coinvolta nello sviluppo di

dipendenza dalle anfetamine.

Metodo:

Deplezione seletiva di NE nella mPFC nei C57BL/6J,

(molto suscettibili allo sviluppo di dipendenza da

anfetamine).

Scopo:

Valutare lo sviluppo di dipendenza da anfetamine con il

conditioned place preference.

Risultati:

Assenza di conditioned place preference nei topi C57

con deplezione prefrontale di NE (C57 sono diventati

DBA).

Effects of prefrontal cortical norepinephrine depletion on the preference scores shown by saline (A)

and amphetamine (B)-treated groups of C57 mice in conditioned place preference test. All data are

expressed as mean ± SE. *p < 0.05 compared with the unpaired compartment.

Ventura et al., 2003

In un secondo gruppo di esperimenti, Ventura et al.,

(2003) hanno mostrato che la deplezione

noradrenergica a livello prefrontale riduce fortemente

l’effetto della anfetamina nell’aumentare il rilascio di

dopamina dalla VTA al nucleo accumbens, in linea con

l’assenza di dipendenza.

“These results indicate that noradrenergic prefrontal

transmission, by allowing increased dopamine

release in the nucleus accumbens induced by

amphetamine, is a critical factor for the rewardingreinforcing effects of this drug.”

Ventura et al., 2003

“Later studies have shown that C57 and DBA mice differ

in their sensitivity to other drugs of abuse (cocaine and

morphine) in terms of drug induced conditioned place

preference and suggest that the two strains differ in

sensitivity to the positive incentive properties of

drugs of abuse (Orsini et al., 2005).” (Pascucci et al.,

2007)

Sembrerebbe quindi che lo sviluppo di dipendenza

dall’assunzione di sostanze, legato al rilascio di

dopamina nel nucleo accumbens (dopamina che è

rilasciata dai neuroni della VTA), sia sotto il controllo

opponente del sistema noradrenergico e dopaminergico

a livello della corteccia prefrontale. (Pascucci et al.,

2007).

In ultima analisi, il bilancio fra attività

noradrenergica e dopaminergica a livello

prefrontale potrebbe, regolando il rilascio di

dopamina nel nucleo accumbens, determinare la

suscettibilità allo sviluppo di dipendenza da

sostanze, attraverso una interazione geni x

ambiente.

Risultati simili per la risposta allo stress.

Esposizione a stressors inibisce il rilascio di dopamina

nel nucleo accumbens.

Nei C57, questo effetto è accompaganto da una forte

attivazione del sistema dopaminergico mesocorticale; a

livello comportamentale, questo corrisponde ad una

messa in atto di comportamenti “rinunciatari” e alla

presenza di anedonia.

Nei DBA si ha invece una risposta neuromodulatoria

prefrontale e comportamentale opposta.

“There may be a genetic control over the balance

between mesocortical and mesoaccumbens

dopamine responses to drugs and stress, which

sets the level of susceptibility for drug addiction,

stressful events and ultimately, interactions with

the environment.”

(Pascucci et al., 2007)

I polimorfismi: fattori di rischio, fattori

protettivi nei confronti di “patogeni”

ambientali.

(Si parla di polimorfismo genetico quando una variazione genetica ha una prevalenza maggiore

dell'1% nella popolazione. La variazione genetica può essere determinata da sostituzioni, delezioni

o inserzioni di basi nel DNA e può riguardare regioni codificanti e regioni non codificanti.)

Lavoro capostipite: Caspi et al., 2002

Role of genotype in the cycle of violence in maltreated children

“Childhood maltreatment is a universal risk factor for antisocial

behavior. Boys who experience abuse--and, more generally, those

exposed to erratic, coercive, and punitive parenting--are at risk of

developing conduct disorder, antisocial personality symptoms, and of

becoming violent offenders.

The earlier children experience maltreatment, the more likely

they are to develop these problems. But there are large differences

between children in their response to maltreatment. Although

maltreatment increases the risk of later criminality by about 50%,

most maltreated children do not become delinquents or adult

criminals.

The reason for this variability in response is largely unknown,

but it may be that vulnerability to adversities is conditional, depending

on genetic susceptibility factors.”

In questo studio, viene indagata l’ipotesi di una

suscettibilità genetica al maltrattamento infantile.

Si ipotizza in particolare che differenze interindividuali

nella funzionalità del gene per la monoamminoossidasi A

(MAOA), dovute ad un polimorfismo nel promotore del

gene stesso, influenzino la resilienza ad un ambiente

avverso precoce.

Ipotesi: “polimorphism in MAOA gene modifies the

influence of maltreatment on children's development

of antisocial behavior.”

Il gene per la MAOA è localizzato sul cromosoma X.

Esso codifica per l’enzima MAOA, che metabolizza

neurotrasmettitori quali la Noradrenalina (NE), serotonina (5-HT),

e dopamina (DA), rendendoli inattivi e facendone quindi terminare

l’azione a livello sinaptico.

Una mutazione che determina la produzione di una versione

meno funzionale della MAOA prolunga la vita media del

neurotrasmettitore, aumentandone l’efficacia sinapitca.

Deficit nella attività della MAOA dovuti a polimorfismi

genetici sono stati messi in relazione con fenotipi a maggior

aggressività sia in modelli animali che nell’uomo.

1: Increased aggression and increased levels of brain NE, 5-HT,

and DA were observed in a transgenic mouse line in which the

gene encoding MAOA was deleted, and aggression was

normalized by restoring MAOA expression.

2: In humans, a null allele at the MAOA locus was linked

with male antisocial behavior in a Dutch kindred.

Because MAOA is an X-linked gene, affected males with a single

copy produced no MAOA enzyme--effectively, a human knockout.

However, this mutation is extremely rare.

Evidence for an association between MAOA

and aggressive behavior in the human general

population remains inconclusive.

Circumstantial evidence suggests the hypothesis

that childhood maltreatment predisposes most

strongly to adult violence among children whose

MAOA is insufficient to constrain maltreatmentinduced changes to neurotransmitter systems.

Indeed, animal studies document that

maltreatment stress (e.g., maternal deprivation, peer

rearing) in early life alters NE, 5-HT, and DA

neurotransmitter systems in ways that can persist into

adulthood and can influence aggressive behaviors

(Harlow, Meaney).

“Maltreatment has lasting neurochemical correlates in

human children: psychobiological sequelae of child

maltreatment may be regarded as an

environmentally induced complex developmental

disorder, and although no study has ascertained

whether MAOA plays a role, it exerts an effect on all

aforementioned neurotransmitter systems.

Posttraumatic stress disorder in maltreated children is

associated with dysregulation of biological stress

systems, adverse brain development, and neuronal loss

in the anterior cingulate region of the medial prefrontal

cortex.”

(Caspi et al., 2000)

Deficient MAOA activity may dispose the

organism toward neural hyperreactivity to threat.

McDermott et al., 2009

Monoamine oxidase A gene (MAOA) has earned the nickname

“warrior gene” because it has been linked to aggression in

observational and survey-based studies.

McDermott and coworkers have performed an experiment,

synthesizing work in psychology and behavioral economics, which

suggests that aggression occurs with greater intensity and

frequency as provocation is experimentally manipulated upwards,

especially among low activity MAOA (MAOA-L) subjects.

Low MAOA activity may be particularly

problematic early in life, because there is

insufficient MAOB (a homolog of MAOA with

broad specificity to neurotransmitter amines) to

compensate for an MAOA deficiency.

Based on the hypothesis that MAOA

genotype can moderate the influence of

childhood maltreatment on neural systems

implicated in antisocial behavior, Caspi et al.

tested

whether antisocial behavior would be

predicted by an interaction between a gene

(MAOA) and an environment (maltreatment).

A well-characterized variable number

tandem repeat (VNTR) polymorphism exists

at the promoter of the MAOA gene, which is

known to affect gene expression.

Caspi’s group genotyped this polymorphism in

members of the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health

and Development Study.

This birth cohort of 1,037 children (52% male)

has been assessed at ages

3, 5, 7, 9, 11, 13, 15, 18, and 21 and was virtually

intact (96%) at age 26 years.

The Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development Study

(often referred to as the Dunedin Longitudinal Study) is a longrunning cohort study of 1037 people born over the course of a

year in Dunedin, New Zealand.

The original pool of study members were selected from those born

between 1 April 1972 and 31 March 1973 and still living in the

Otago region 3 years later.

Study members were assessed at age 3, and then at ages 5, 7, 9,

11, 13, 15, 18, 21, 26, 32 and, most recently, at age 38 (20102012). Future assessments are scheduled for ages 44 and 50.

Avshalom Caspi and Terrie Moffitt

During an assessment, study members are brought back to

Dunedin from wherever in the world they live. They participate in a

day of interviews, tests and surveys.

Sub-studies of the Dunedin Study include the on-going Parenting

Study which focuses on the Dunedin Study member and their first

three-year-old child;

and the Next Generation Study which involves the offspring of

Dunedin Study members as they turn 15 and looks at the

lifestyles, behaviours, attitudes and health of today's teenagers,

and aims to see how these have changed from when the original

Study Members were 15 (in 1987-88).

This means that information across three generations of the same

families will be available.

Great emphasis is placed on retention of study

members.

At the most recent (age 38) assessments, 96% of

all living eligible study members, or 961 people,

participated.

This is unprecedented for a longitudinal study,

with many others worldwide experiencing 20–

40% drop-out rates.

The Caspi et al. 200 study.

The study offers three advantages for testing gene-environment

(G × E) interactions.

First, in contrast to studies of clinical samples, this study of a

representative general population sample avoids potential

distortions in association between variables.

Second, the sample has well-characterized environmental

adversity histories.

Between the ages of 3 and 11 years, 8% of the study children

experienced "severe" maltreatment, 28% experienced "probable"

maltreatment, and 64% experienced no maltreatment.

(Maltreatment groups did not differ on MAOA activity, suggesting

that genotype did not influence exposure to maltreatment.)

Third, the study has ascertained antisocial outcomes

rigorously.

Antisocial behavior is a complicated phenotype, and each method and data

source used to measure it (e.g., clinical diagnoses, personality checklists,

official conviction records) is characterized by different strengths and

limitations.

Using information from independent sources appropriate

to different stages of development, Caspi et al.,

examined four outcome measures.

A common-factor model fit the four measures of antisocial behavior well, with

factor loadings ranging from 0.64 to 0.74, showing that all four measures index

liability to antisocial behavior.

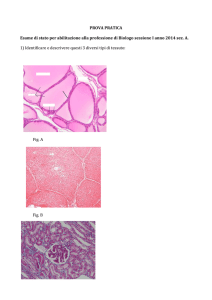

1 Adolescent conduct disorder was assessed according

to criteria of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders (DSM-IV);

2 Convictions for violent crimes were identified via the

Australian and New Zealand police;

3 A personality disposition toward violence was

measured as part of a psychological assessment at age

26;

4 Symptoms of antisocial personality disorder were

ascertained at age 26 by collecting information about the

study members from people they nominated as

"someone who knows you well."

Means on the composite

index of antisocial

behavior as a function of

MAOA activity and a

childhood history of

maltreatment .

MAOA activity is the gene

expression level associated

with allelic variants of the

functional promoter

polymorphism, grouped into

low and high activity;

childhood maltreatment is

grouped into 3 categories of

increasing severity.

The antisocial behavior

composite is standardized

(z score) to a M = 0 and

SD = 1; group differences

are interpretable in SD unit

differences (d).

A test of the interaction between MAOA activity and maltreatment revealed a significant G × E interaction

(P = 0.01). This interaction within each genotype group showed that

effect of childhood maltreatment on antisocial behavior was significantly weaker

among males with high MAOA activity (P = 0.03) than among males with low

MAOA activity (P < 0.001).

*

*

*

*

*

*

Effect of maltreatment significant

Association between childhood

maltreatment and subsequent antisocial

behavior as a function of MAOA activity.

(A) Percentage of males (and standard

errors) meeting diagnostic criteria for

Conduct Disorder between ages 10 and

18. In a hierarchical logistic regression

model, the interaction between

maltreatment and MAOA activity was in

the predicted direction, P = 0.06. Probing

the interaction within each genotype

group showed that the effect of

maltreatment was highly significant in the

low-MAOA activity P < 0.001, and

marginally significant in the high-MAOA

group P = 0.09). (B) Percentage of males

convicted of a violent crime by age

26. The G × E interaction was in the

predicted direction, p = 0.05. Probing the

interaction, the effect of maltreatment

was significant in the low-MAOA activity

P < 0.001), but was not significant in the

high MAOA group P = 0.17. (C) Mean z

scores (M = 0, SD = 1) on the Disposition

Toward Violence Scale at age 26. G × E

interaction was in the predicted

direction, P = 0.10); the effect of

maltreatment was significant in the lowMAOA activity P = 0.002) but not in the

high MAOA group P = 0.17). (D) Mean z

scores (M = 0, SD = 1) on the Antisocial

Personality Disorder symptom scale at

age 26. The G × E interaction was in the

predicted direction P = 0.04); the effect of

maltreatment was significant in the lowMAOA activity P < 0.001) but not in the

high MAOA group P = 0.12).

Although individuals having the combination of

low-activity MAOA genotype and maltreatment were

only 12% of the male birth cohort, they accounted for

44% of the cohort's violent convictions, yielding an

attributable risk fraction (11%) comparable to that of

the major risk factors associated with cardiovascular

disease.

Moreover, 85% of cohort males having a lowactivity MAOA genotype who were severely

maltreated developed some form of antisocial

behavior.

“These findings provide initial evidence that a

functional polymorphism in the MAOA gene moderates

the impact of early childhood maltreatment on the

development of antisocial behavior in males.” (Caspi et al., 2000)

Questo lavoro è stato il primo a mostrare

chiaramente che un fattore genetico poteva rendere

resilienti nei confronti di un patogeno ambientale.

“With regard to research in psychiatric

genetics, knowledge about environmental context

might help gene-hunters refine their phenotypes.

Genetic effects in the population may be

diluted across all individuals in a given

sample, if the effect is apparent only among

individuals exposed to specific environmental

risks.

Environment effect in the population may be

masked across all individuals in a given

sample, if the effect is apparent only among

individualscarrying a specific polymorphism”

“With regard to research on child health, knowledge

about specific genetic risks may help to clarify risk

processes.

The search has focused on social experiences that may

protect some children, overlooking a potential protective role

of genes.

Genes are assumed to create vulnerability to

disease, but from an evolutionary perspective they

are equally likely to protect against environmental

insult.

Maltreatment studies may benefit from

ascertaining genotypes associated with sensitivity

to stress, and the known functional properties of

MAOA may point toward hypotheses, based on

neurotransmitter system development, about how

stressful experiences are converted into

antisocial behavior toward others in some, but not

all, victims of maltreatment.

Caspi et al., 2003

Influence of Life Stress on Depression: Moderation by a

Polymorphism in the 5-HTT Gene

“Across the life span, stressful life events that

involve threat, loss, humiliation, or defeat influence the

onset and course of depression.

However, not all people who encounter a stressful

life experience succumb to its depressogenic effect.”

Costello et al., 2002

The NIMH convened a multidisciplinary Workgroup of

scientists to review the field and the NIMH portfolio and to

generate specific recommendations.

To encourage a balanced and creative set of proposals,

experts were included within and outside this area of research, as

well as public stakeholders.

The Workgroup identified the need for expanded knowledge of

mood disorders in children and adolescents, noting important

gaps in understanding the onset, course, and recurrence of earlyonset unipolar and bipolar disorder. Recommendations included

the need for a multidisciplinary research initiative on the

pathogenesis of unipolar depression encompassing genetic and

environmental risk and protective factors.

Whether specific genes exacerbate or buffer the effect of

stressful life events on depression is beginning to be unravelled.

In this study, a functional polymorphism in the

promoter region of the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTT)

was used to characterize genetic vulnerability to depression

and to test whether 5-HTT gene variation moderates the

influence of life stress on depression.

The 5-HT system provides a logical source of candidate

genes for depression, because this system is the target of

selective serotonin reuptake–inhibitor drugs that are effective in

treating depression.

The 5-HTT has received particular attention because it is involved

in the reuptake of serotonin at brain synapses.

The promoter activity of the 5-HTT gene is

modified by sequence elements within the

proximal 5' regulatory region, designated

the 5-HTT gene-linked polymorphic region

(5-HTTLPR).

The short ("s") allele in the 5-HTTLPR is

associated with lower transcriptional

efficiency of the promoter compared with

the long ("l") allele.

Up to Caspi’s work, evidence for an association between

the short promoter variant and depression was

inconclusive.

Although the 5-HTT gene may not be directly

associated with depression, it could moderate the

serotonergic response to stress.

Three lines of experimental research suggested this

hypothesis of a gene-by-environment (G x E) interaction.

First, in mice with disrupted 5-HTT, homozygous

and heterozygous (5-HTT –/– and +/–) strains

exhibited more fearful behavior;

in response to stress they showed greater

increases in the stress hormone (plasma)

adrenocorticotropin compared to homozygous (5HTT +/+) controls, but in the absence of stress no

differences related to genotype were observed.

5-HTT KO mice

Behaviour in the elevated plus maze

The 5-HT1A receptor antagonist, WAY 100635,

produced anxiolytic-like effects in the EPM

Second, in rhesus macaques, whose length

variation of the 5-HTTLPR is analogous to that of

humans, the short allele is associated with decreased

serotonergic function [lower cerebro-spinal fluid (CSF)

concentrations of 5-HT metabolites] among monkeys

reared in stressful conditions but not among

normally reared monkeys.

Monkeys with deleterious early rearing experiences

were differentiated by genotype in cerebrospinal

fluid concentrations of the 5-HT metabolite, 5hydroxyindoleacetic acid, while monkeys reared

normally were not.

Questi risultati dimostrano che l’effetto del

genotipo (s/s, l/l, s/l) del 5-HTT sulla funzione

serotoninergica nel SNC dipende dall’ambiente.

Una cosa molto importante è che anche la

risposta allo stress è modificata in s/s carriers

esposti a stress precoce (peer rearing)

Caspi et al. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7, 583–590 (July 2006) | doi:10.1038/nrn1925

Influence of exposure to early stress (peer rearing) on subsequent exaggerated responses

of the HPA responses to stress is conditioned by serotonin transporter gene promoter

variation (rh-5HTTLPR) in rhesus macaques. When exposed to stress later in life, peer-reared

animals with the s/l genotype had higher ACTH levels than animals with the l/l genotype. There

were no differences between genotypes among animals reared with their mothers

Fin qui 28 ottobre

l/l

Trattatemi con

cura, sono un

s/s

s/s

An alert monkey and a depressed monkey.

"Depressed monkeys do not appear responsive to potential threats. It's that slumped,

collapsed body posture accompanied by a lack of responsiveness to environmental

events.“

As in humans, monkey depression is deeper than just mopey behavior. The depressed

macaques had less body fat, higher levels of stress hormones, lower bone density

(consistent with osteoporosis), higher cholesterol concentrations and high heart rates.

They were often subordinate in the community hierarchy and socially stressed by

dominant animals.

Third, human neuroimaging research suggests that the fear

response (and therefore the stress response) is mediated by

variations in the 5-HTTLPR. Humans with one or two copies of the

s allele exhibit greater amygdala neuronal activity to fearful stimuli

compared to individuals homozygous for the l allele.

Effect of 5-HTT genotype on right

amygdala activity. Bar graphs

represent the mean BOLD fMRI

percent signal change in a region of

interest (ROI) comprising the entire

right amygdala in the s (n = 14) and

l (n = 14) groups collapsed across

both cohorts. Individual circles

represent the activity for each

subject in this ROI. Consistent with

the statistical parametric maps (Fig.

2), which identified significant voxels

within the right amygdala, analysis

of variance for the entire amygdala

ROI, including voxels that were not

differentially activated according to

statistical parametric mapping, still

revealed significant group

differences in the mean (±SEM)

BOLD fMRI percent signal change

[s group = 0.28 ± 0.08 and l

group = 0.03 ± 0.05;

F(1,26) = 6.84, P = 0.01].

Presi nel loro insieme, questi risultati

costituiscono un sufficiente razionale per

formulare l’ipotesi che variazioni a carico del

gene del 5-HTT possano moderare le reazioni ad

espereinze avverse, rendendo gli individui

resilienti o vulnerabili.

Caspi tested this G x E hypothesis among members of

the Dunedin Multidisciplinary Health and Development

Study. This representative birth cohort of 1037 children

(52% male) has been assessed at ages 3, 5, 7, 9, 11,

13, 15, 18, and 21 and was virtually intact (96%) at the

age of 26 years.

Stressful life events occurring after the 21st birthday

and before the 26th birthday were assessed with the

aid of a life-history calendar, a highly reliable method for

ascertaining life-event histories.

The 14 events included employment, financial, housing,

health, and relationship stressors.

Thirty percent of the study members experienced

no stressful life events; 25% experienced one

event; 20%, two events; 11%, three events; and

15%, four or more events.

There were no significant differences between

the three genotype groups in the number of

life events they experienced, F(2,846) = 0.56, P

= 0.59, suggesting that 5-HTTLPR genotype

did not influence exposure to stressful life

events.

* Main effect of

5-HTT genotype significance

* (p 0.06)

Results of multiple regression analyses estimating the association between number of stressful life

events (between ages 21 and 26 years) and depression outcomes at age 26 as a function of 5HT T genotype.

(A) Self-reports of depression symptoms. The main effect of 5-HT TLPR (i.e., an effect not conditional on

other variables) was marginally significant (P = 0.06), the main effect of stressful life events was

significant (P < 0.001), and the interaction between 5-HT TLPR and life events was in the predicted

direction (P = 0.02). The interaction showed that the effect of life events on self-reports of

depression symptoms was stronger among individuals carrying an s allele (P < 0.001 among

s/s homozygotes, and P < 0.001 among s/l heterozygotes) than among l/l homozygotes ( P = 0.08).

(B) Probability of major depressive episode. The main effect of 5-HT TLPR was not significant (P = 0.29),

the main effect of life events was significant (P < 0.001), and the G x E was in the predicted direction

(P = 0.056). Life events predicted a diagnosis of major depression among s carriers (P = 0.001

among s/s homozygotes, and P < 0.001 among s/l heterozygotes) but not among l/l

homozygotes (P = 0.24).

Probability of suicide ideation or attempt. The main effect of 5-HT TLPR was not

significant (P = 0.99), the main effect of life events was significant (P < 0.001), and the G

x E interaction was in the predicted direction (P = 0.051). Life events predicted suicide

ideation or attempt among s carriers (, P = 0.09 among s/s homozygotes, and P <

0.001 among s/l heterozygotes) but not among l/l homozygotes (P = 0.62).

Caspi reasoned that if measure of life events

represents environmental stress, then the timing

of life events relative to depression must follow

cause-effect order and life events that occur after

depression should not interact with 5-HTTLPR to

postdict depression.

Caspi tested this hypothesis by substituting the age-26

measure of depression with depression assessed in

this longitudinal study when study members were 21

and 18 years old, before the occurrence of the

measured life events between the ages of 21 and 26

years.

Whereas the 5-HTTLPR x life events interaction

predicted depression at the age of 26 years, this same

interaction did not postdict depression reported at age

21 nor at the age of 18 years, indicating that the above

realted finding is a true G x E interaction.

If 5-HTT genotype moderates the depressogenic

influence of stressful life events, it should moderate the

effect of life events that occurred not just in adulthood

but also of stressful experiences that occurred in earlier

developmental periods.

Based on this hypothesis, Caspi tested whether

adult depression was predicted by the interaction

between 5-HTTLPR and childhood maltreatment that

occurred during the first decade of life. Consistent

with the G x E hypothesis, the longitudinal prediction

from childhood maltreatment to adult depression was

significantly moderated by 5-HTTLPR.

The interaction showed that childhood

maltreatment predicted adult depression only

among individuals carrying an s allele but not

among l/l homozygotes.

Results of regression analysis estimating the association between childhood maltreatment

(between the ages of 3 and 11 years) and adult depression (ages 18 to 26), as a function of 5HT T genotype. Among the 147s/s homozygotes, 92 (63%), 39 (27%), and 16 (11%) study members were in

the no maltreatment, probable maltreatment, and severe maltreatment groups, respectively. Among the 435 s/l

heterozygotes, 286 (66%), 116 (27%), and 33 (8%) were in the no, probable, and severe maltreatment groups.

Among the 265 l/l homozygotes, 172 (65%), 69 (26%), and 24 (9%) were in the no, probable, and severe

maltreatment groups. The main effect of 5-HT TLPR was not significant (b = –0.14, SE = 0.11, z = 1.33, P =

0.19), the main effect of childhood maltreatment was significant (b = 0.30, SE = 0.10, z = 3.04, P = 0.002), and the

G x E interaction was in the predicted direction (b = –0.33, SE = 0.16, z = 2.01, P = 0.05). The interaction showed

that childhood stress predicted adult depression only among individuals carrying an s allele (b = 0.60, SE

= 0.26, z = 2.31, P = 0.02 among s/s homozygotes, and b = 0.45, SE = 0.16, z = 2.83, P = 0.01 among s/l

heterozyotes) and not among l/l homozygotes (b = –0.01, SE = 0.21, z = 0.01, P = 0.99).

Evidence of a direct relation between the 5-HTTLPR

and depression had been inconsistent, perhaps because

prior studies have not considered participants' stress

histories.

In this study, no direct association between the 5-HTT gene

and depression was observed.

Previous experimental paradigms, including 5-HTT

knockout mice, stress-reared rhesus macaques, and human

functional neuroimaging, have shown that the 5-HTT gene can

interact with environmental conditions, although these

experiments did not address depression.

Caspi’s study demonstrates that this G x E interaction

extends to the natural development of depression in a

representative sample of humans.

Cosa abbiamo imparato dai lavori di Caspi e da

altri simili

“The study of gene–environment interactions has been the

province of epidemiology, in which genotypes, environmental

pathogen exposures and disorder outcomes are studied as they

naturally occur in the human population.

Genetic epidemiology is ideal for achieving three goals.

First, epidemiological studies identify the involvement of

hypothesized gene–environment interactions.

Second, to increase confidence in the interaction, epidemiological

studies incorporate control factors necessary for ruling out

alternative explanations.

Third, epidemiological studies attest whether an interaction

accounts for a non-trivial proportion of the disorder in the human

population. “

However, genetic epidemiology is limited for

understanding the biological mechanisms

involved in an interaction, and therefore its

potential will be better realized when it is

integrated with experimental neuroscience

(psychobiology).

Psychobiology can complement psychiatric

genetic epidemiology by specifying the more

proximal role of nervous system reactivity in the

gene–environment interaction.

Caspi et al. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7, 583–590 (July 2006) | doi:10.1038/nrn1925

The building blocks

correspond to the three

elements of the triad: the

disorder, the

environmental pathogen

and the genotype. First,

evidence is needed about

which neural substrate

is involved in the

disorder. Second,

evidence is needed that

an environmental cause

of the disorder has

effects on variables

indexing the same

neural substrate. Third,

evidence is needed that a

candidate gene has

functional effects on

variables indexing that

same neural substrate.

It is this convergence of

environmental and

genotypic effects within

the same neural substrate

that allows for the

possibility of gene–

environment interactions.

Caspi et al. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 7, 583–590 (July 2006) | doi:10.1038/nrn1925

Psychobiology provides the building blocks for constructing hypotheses about gene–

environment interaction (a) that are tested against data (b), subsequently stimulating new

studies to illuminate the black box of biology (c) between the gene (G), the environmental

pathogen (E) and the disorder (D).

Several studies have sought to replicate the interaction

between the high- and low-activity MAOA genotypes and

maltreatment found by Caspi et al.; a recent metaanalysis revealed a significant pooled effect.

Positive replications of the interaction between 5HTT*long/5HTT*short genotypes and life stress have

also appeared, along with two failures to replicate.

Other studies have found G xE for other genes, such as

BDNF, in relation to mood disorders.

Brain galanin system genes interact with life stresses in

depression-related phenotypes.

Juhasz G, Hullam G, Eszlari N, Gonda X, Antal P, Anderson IM,

Hökfelt TG, Deakin JF, Bagdy G Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014

Apr 22;111(16):E1666-73

Galanin is a stress-inducible neuropeptide and cotransmitter in

serotonin and norepinephrine neurons with a possible role in

stress-related disorders. Galaninis widely distributed in the rodent

and human brain.

In rat it coexists with noradrenaline (NA) in the locus coeruleus

(LC) and with 5-HT in the dorsal raphe complex. Like other

peptide cotransmitters, it is released when neurons fire in highfrequency bursts in response to strong behavioral and

pharmacological challenge

Variants in genes for galanin (GAL) and its receptors (GALR1,

GALR2, GALR3), conferred increased risk of depression and

anxiety in people who experienced childhood adversity or recent

negative life events in a European white population cohort totaling

2,361 from Manchester, United Kingdom and Budapest, Hungary.

The results suggest that the galanin pathway plays an important

role in the pathogenesis of depression in humans by increasing

the vulnerability to early and recent psychosocial stress.

The findings further emphasize the importance of

modeling environmental interaction in finding new

genes for depression

Galanin mechanisms hypothetically involved in MDD in humans. Galanin, a

neuropeptide, and its receptors are colocalized in some monoaminergic

neurons in the brain. The galanin system is highly sensitive to experimental

and naturalistic stressors.

Recent analysis of human brain has shown that the GALR3 is the main

galanin receptor in NA-LC and probably 5-HT dorsal raphe nucleus cells, and

that the GALR1 is the main receptor in the forebrain.

Antidepressive effects may be achieved by (i) GALR3 antagonists, by

reinstating normal monoamine turnover in the brainstem, and by (ii) GALR1

antagonists in the forebrain by normalization of limbic system activity, or by

(iii) agonists at GALR2, promoting neuroprotection.

The present genetic analysis suggests that GALR1 risk variants may

compromise galanin signaling during childhood, whereas GALR2 signaling

may be influenced by recent negative life events.

In addition, all four galanin system genes have relevant roles in the

development of depression-related phenotypes in those persons who were

highly exposed to life stressors.

Three-way interaction effect of 5-HTTLPR, BDNF Val66Met,

and childhood adversity on depression: a replication study.

Comasco E, Åslund C, Oreland L, Nilsson KW. Eur

Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013 Oct;23(10):1300-6.

Both the serotonin transporter linked promoter region (5-HTTLPR)

and the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) Val66Met

polymorphisms have been shown to interact with unfavourable

environment in relation to depression symptoms and to

depression diagnosis.

Several attempts have been made to study a three-way

interaction effect of these factors on depression, however with

contradictory results.

This paper aimed to test the hypothesis of a three-way interaction

effect and to attempt at replication in an independent populationbased sample.

Family maltreatment and depression were self-reported by an

adolescent population-based cohort (N=1393) from the county of

Västmanland, Sweden.

DNA was isolated from saliva, and used for genotyping of the 5HTTLPR and BDNF Val66Met polymorphisms.

Neither 5-HTTLPR or BDNF genotypes separately, nor

in interaction with each other had any relation to

depression, however in an environment adjusted model

a two-way interaction and a three-way interaction effect

was found.

Both 5-HTTLPR and BDNF Val66Met interacted with

unfavourable environment in relation to depressive

symptoms.

Depressive symptoms and depression were more

common among carriers of either the ss/sl+Val/Val or the

ll+Met genotypes in the presence of early-life

adversities. This three-way effect was more pronounced

among girls.

Interazioni G x E nella lunghezza dei telomeri: effetti di

esperienze precoci avverse sulla integrità del DNA tramite i

telomeri

I telomeri impediscono la degradazione progressiva dei

cromosomi con rischio di perdita di informazione genetica.

Social disadvantage, genetic sensitivity, and

children's telomere length.

Mitchell C, Hobcraft J, McLanahan SS, Siegel SR, Berg A,

Brooks-Gunn J, Garfinkel I, Notterman D. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S

A. 2014 Apr 22;111(16):5944-9.

Disadvantaged social environments are associated with adverse

health outcomes. This has been attributed, in part, to chronic

stress.

Results:

Exposure to disadvantaged environments is associated

with reduced telomere length (TL) by age 9 years.

There is a significant associations between low income,

low maternal education, unstable family structure, harsh

parenting and TL.

These effects were moderated by genetic variants in

serotonergic and dopaminergic pathways.

Consistent with the differential susceptibility hypothesis,

subjects with the “vulnerable” genotype had the shortest

TL when exposed to disadvantaged social environments

and the longest TL when exposed to advantaged

environments

Other G x E interactions

Evidence from studies around the world shows that cannabis use

is a statistical risk factor for the emergence of psychosis,

ranging from psychotic symptoms (such as hallucinations and

delusions) to clinically significant disorders.

However, most people who use cannabis do not develop

psychosis, which suggests that some individuals may be

genetically vulnerable to its effects.

Which is the genetic risk factor?

COMT gene polymorphism???

Individuals with one or more

high-activity valine alleles

(VAL/METor VAL/VAL) showed

subsequent increased risk of

psychotic symptoms and

psychosis-spectrum disorder if

they used cannabis.

Cannabis use had no such

adverse influence on individuals

with two copies of the methionine

allele (MET/MET).

Results of an epidemiological study that traced a longitudinal

cohort from prior to the onset of cannabis use (age 11 years),

through to the peak risk period of psychosis onset (age 26 years)

Cannabis affects in subjects with different genotype

Subjects were tested on two occasions, separated by 1 week, as

part of a double-blind, placebo controlled cross-over design.

In randomized order, they received either 0 g or 300 g -9tetrahydrocannabinol (the principal component of cannabis) per

kilogram bodyweight.

Cannabis affected cognition and state psychosis, but this

was conditional on COMT genotype.

Individuals carrying two

copies of the valine

allele exhibited more

cannabis-induced

memory and attention

impairments than

carriers of the

methionine allele, and

were the most sensitive

to cannabis-induced

psychotic experiences.

Vulnerabilità genetica verso la dipendenza da

sostanze: dati nell’uomo

In one experiment, the researchers investigated whether

a polymorphism in the D4 dopamine receptor gene

(DRD4) affected craving after priming doses and drug

cues.

Participants were tested on two occasions, randomly

assigned to receive three alcoholic drinks on the first

session and three control drinks on the second session,

or the reverse.

Individuals carrying the DRD4 long (L) allele reported

a stronger urge to drink in the alcohol condition than

in the placebo condition. By contrast, individuals with

two short DRD4 alleles (S) reported no differences in the

urge to drink between the two conditions.

These findings suggest that the DRD4

polymorphism moderates craving after

alcohol consumption, and indicate that

DRD4*L individuals may be more

susceptible to losing control over drinking

But the DRD4 polymorphism is not simply a genetic risk for alcohol abuse.

Individuals carrying the L allele also experience more craving and arousal after

exposure to tobacco smoking cues, whereas DRD4*S individuals do not.

This suggests that DRD4 may influence the incentive salience of

appetitive stimuli more generally, and offers a clue as to why

different addictive disorders tend to co-occur in the same

individuals.

Much genetic research has been guided by the

assumption that genes cause diseases, but the expectation

that direct paths will be found from gene to disease has not

proven fruitful for complex psychiatric disorders.

Findings of G x E interaction point to a different, evolutionary

model.

This model assumes that genetic variants maintained

at high prevalence in the population probably act to promote

organisms' resistance to environmental pathogens.

They extend the concept of environmental pathogens to

include traumatic, stressful life experiences and propose that the

effects of genes may be uncovered when such pathogens are

measured (in naturalistic studies) or manipulated (in experimental

studies).

Futura facenda

The characterization of subjects' genetic vulnerability

as opposed to their resilience needs to move beyond

single genetic polymorphisms.

New approaches will use information about biological

pathways to identify gene systems and study sets of

genetic polymorphisms that are active in the

pathophysiology of a disorder.

For example, in relation to depression, information

about the psychobiology of psycho-social stress can

be used as a first step to characterize a set of genes

that define a genotype that is vulnerable as opposed

to resilient to stressful life events.

Incorporating information about genetic pathways

into gene–environment interaction studies will

enhance explanatory power, but it will also

present unique statistical challenges related to

the use of data-mining tools and the pooling of

data across different studies.

If environmental risk exposure differs

between samples, candidate genes may

fail replication.

If environmental risk exposure differs

among participants within a sample,

genes may account for little variation in

the phenotype.

Hypothesis

Some multifactorial disorders, instead of

resulting from variations in many genes

of small effect, may result from

variations in fewer genes whose effects

are conditional on exposure to

environmental risks.

Necessity of implementing gene x

environment interaction research protocols

Necessity of accurate phenotyping

Interazioni geni ambiente nel Bucharest Early

Intervention Project

Charles Nelson III

Cosa è il Bucharest Early Intervention project

Science, 2008

Modification of depression by COMT val158met polymorphism

in children exposed to early severe psychosocial deprivation.

Drury SS, Theall KP, Smyke AT, Keats BJ, Egger HL, Nelson CA,

Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Zeanah CH. (2010)

OBJECTIVE:

To examine the impact of the catechol-O-methyltransferase

(COMT) val(158)met allele on depressive symptoms in young

children exposed to early severe social deprivation as a result of

being raised in institutions.

METHODS:

One hundred thirty six children from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project

(BEIP) were randomized before 31 months of age to either care as usual (CAU)

in institutions or placement in newly created foster care (FCG). At 54 months of

age, a psychiatric assessment using the Preschool Age Psychiatric Assessment

(PAPA) was completed. DNA was collected and genotyped for the COMT

val(158)met polymorphism. Multivariate analysis examined the relationship

between COMT alleles and depressive symptoms.

RESULTS:

Mean level of depressive symptoms was lower among

participants with the met allele compared to those with two

copies of the val allele (P<0.05).

Controlling for group and gender, the rate of depressive symptoms

was significantly lower among participants with the met/met or the

met/val genotype [adjusted relative risk (aRR)=0.67, 95% CI=0.45,

0.99] compared to participants with the val/val genotype, indicating

an intermediate impact for heterozygotes consistent with the

biological impact of this polymorphism.

The impact of genotype within groups differed significantly.

There was a significant protective effect of the met allele on

depressive symptoms within the CAU group, however there

was no relationship seen within the FCG group.

.

CONCLUSIONS:

This is the first study to find evidence of a gene x

environment interaction in the setting of early social

deprivation.

These results support the hypothesis that individual

genetic differences may explain some of the variability in

recovery amongst children exposed to early severe

social deprivation