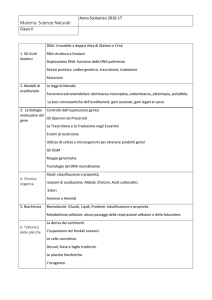

Corso integrativo al Corso di Diritto Costituzionale

Nuovi diritti di libertà

Anno Accademico 2008-2009

Prof.ssa Valentina Sellaroli

LE APPLICAZIONI DELLA GENETICA TRA

FAMILIARITA’ E DISCRIMINAZIONE

PROFILI PENALISTICI

LA FAMILIARITA’ DELLE CARATTERISTICHE

GENETICHE

LA BANCA DATI DEL DNA IN Italia: normativa, d.d.l.,

giurisprudenza

IL PRELIEVO COATTIVO

15 maggio 2009

1

DNA (CODICE O PROFILO GENETICO)

• Strumento di analisi ed oggetto di

studio a fini terapeutici o di ricerca

• Strumento di identificazione a fini

forensi per il suo potere informativo e

per le sue caratteristiche di “unicità ed

individualità”…

…ma è davvero così?

15 maggio 2009

2

COME SI ARRIVA ALLA

IDENTIFICAZIONE TRAMITE IL DNA?

• Raccolta di campioni biologici

• Estrazione del dna dai materiali e dai tessuti che lo

contengono

• Eventuale amplificazione del materiale genetico trovato

• Studio delle sequenze genomiche utilizzate come

marcatori

• Lettura e valutazione dei risultati alla luce di conoscenze

statistico-scientifiche acquisite

15 maggio 2009

3

L’ESAME DEL DNA può condurre

• Alla conoscenza del genotipo di un essere umano, cioè

del suo “programma genetico” che in parte è ciò che un

individuo appare all’esterno (fenotipo)

• Alla valutazione della probabilità con cui un certo tessuto

o un certo materiale biologico è da attribuire ad un

determinato individuo ed a lui solo (capacità identificativa

del DNA)

15 maggio 2009

4

corrisponde grosso modo alla differenza tra

• Sequenze genomiche cd. codificanti

e

• Sequenze genomiche cd. non codificanti

15 maggio 2009

5

RAGIONI DELLA SCELTA DELLE SEQUENZE

NON CODIFICANTI COME MARCATORI AD

USO FORENSE

• Necessità di evitare discriminazioni anche solo potenziali,

ad esempio su base razziale

• Difficoltà anche sociali a condurre studi genetici non su

popolazioni ma su blocchi di individui caratterizzati non

tanto da provenienza etnica quanto da determinate

caratteristiche genetiche che si esprimono in un certo

fenotipo

• Non pacificità e quantificabilità di criteri statistici

identificativi basati su questi parametri di classificazione

15 maggio 2009

6

IL DNA COME IMPRONTA DIGITALE

• DNA fingerprinting: l’impronta digitale genetica è unica ed

univoca?

2 ordini di domande:

• Il profilo genetico identifica con certezza l’individuo al

quale appartiene? Con che margine di errore?

• Il profilo genetico identifica SOLO l’individuo al quale

appartiene?

NO…

15 maggio 2009

7

IL “GRUPPO BIOLOGICO”

• I dati genetici sono ereditabili nell’ambito della famiglia

biologica

• I dati genetici sono anche condivisi nell’ambito di persone

legate da vincolo biologico

Che cosa comporta ciò?…

15 maggio 2009

8

…sul piano investigativo

• Il dato genetico non serve più solo a comparare due profili

genetici (quello trovato sulla scena del crimine e quello del

o dei potenziali sospettati) ma anche…

• …a cercare un sospettato potenziale in un ambito

potenzialmente illimitato

Come?

• Attraverso ricerche, per così dire, indirette , potremmo dire

de relato

15 maggio 2009

9

Un caso concreto: Dobbiaco

Aprile 2002: una anziana donna viene trovata

violentata ed uccisa nel paesino di Dobbiaco.

Abbondanti tracce biologiche sulla vittima.

I principali sospettati vengono esclusi dalle

primissime indagini.

Gli investigatori sono convinti che l’assassino sia

“uno del posto” e notano una notevole

omogeneità tra i profili genetici degli abitanti del

luogo…

Non ci sono altri sospettati

15 maggio 2009

10

SCREENING DI MASSA

(intelligence led-screen)

• Quasi tutti gli abitanti maschi del paesino “donano” il loro

DNA per essere esclusi dal novero dei sospettati

• Viene finalmente trovata una corrispondenza parziale

molto interessante tra uno dei “donatori” ed il profilo

genetico dell’assassino: i due profili corrispondono al 50%

• Il cerchio si chiude. La low-stringency search ha ottenuto il

suo scopo: l’anziano signore è il padre dell’assassino

15 maggio 2009

11

DATO GENETICO CONDIVISO

• Nuovo concetto di identità e di identificazione: non più

solo l’identità assoluta e diretta ma una identità relativa ed

indiretta che si estende a tutti coloro che condividono

parzialmente lo stesso patrimonio genetico

…

15 maggio 2009

12

DATO GENETICO CONDIVISO

• Che conseguenze ha ciò sul piano del valore e della

disciplina dell’analisi del DNA sul piano investigativo e

forense?

15 maggio 2009

13

La legge

• Vuoto legislativo anche sulla questione dell’acquisizione

del campione biologico da cui estrarre il profilo genetico:

art. 224 co. 2 c.p.p. come modificato dalla sentenza Corte

Cost. n. 238/96:

non sono più possibili da parte del giudice “altri

provvedimenti necessari per la esecuzione delle

operazioni peritali”

15 maggio 2009

14

I principi costituzionali

• Articolo 13 Cost.:

Diritti di libertà personale non solo e non tanto nel senso di

inviolabilità fisica, ma anche nel senso di inviolabilità

personale in senso lato:

riservatezza informazionale

15 maggio 2009

15

ne consegue

Un nuovo doppio livello di privacy:

uno diretto ed individuale

un altro personale ma indiretto ed allargato alla cerchia dei

congiunti di ciascun individuo

15 maggio 2009

16

il consenso richiesto agli abitanti di Dobbiaco

(de iure condendo)

• È stato un “consenso informato”?

• Doveva esserlo?

• Che ne è stato della tutela della riservatezza dei congiunti

e del riconoscimento del sentimento di pietas familiare che

pure trova spazio nel nostro ordinamento processuale

(art. 199 c.p.p.)?

15 maggio 2009

17

il consenso richiesto agli abitanti di Dobbiaco

(de iure condito)

• Che cosa sarebbe successo se l’assassino non avesse

confessato?

15 maggio 2009

18

Banche dati genetiche e familial searching

• Caso Harman (UK, 2003)

• Caso Herisch (Germania, 2005)

“…ma la polizia federale non è una organizzazione criminale e

dunque non ci sono da temere abusi…”

• Caso Harper vs UK (ECHR, 2008)

15 maggio 2009

19

Banche dati genetiche e familial searching

Caso Harman (UK, 2003)

Surrey (UK)

Mr. Craig Harman was convicted of manslaughter on the basis of “familial DNA

searching” which linked him to the crime scene via a close relative’s DNA

profile. Harman threw a brick from a bridge over a motorway which crashed

through the windscreen of a lorry. The brick hit driver’s chest and killed him.

Police obtained a DNA profile of the assailant from blood on the brick, but

could not match it to anything on the UK’s national Databank because

Harman had no criminal convictions. The Police used familial searching to

uncover a close relative of Harman’s, who had a criminal conviction and was

on the DNA bank. The relative’s profile matched the DNA on the brick by 16

out of 20 locations. This lead the Police to Harman, whose DNA gave a

perfect match.

He confessed the crime.

15 maggio 2009

20

Banche dati genetiche e familial searching

Caso Herisch (Germania, 2005)

Rudolph Mooshammer, a famous aute couture tailor and

eccentric person, was murdered after a tragic altercation for

an unpaid homosexual affair

Policemen found some murderer’s hair on the crime scene and

extracted a clear DNA profile of the crime’s author

In 36 hours Police reached the murderer, Mr. H. Herish and a

perfect match with his DNA profile was found

The problem:

German police found Mr. Herish searching in the national

DNA database but his profile should not have been stored

into the database

He gave his bio-sample years before in order to be excluded

from another criminal investigation and, according to the

German

law, he should have been excluded after that. 21

15 maggio

2009

Le questioni in gioco:

• Ciascun profilo genetico inserito in banca dati reca

informazioni relativamente non ad un solo individuo ma a

tutto il suo “gruppo biologico”

• È possibile identificare così un numero di persone ben

maggiore dei profili inseriti in banca dati

• Quale valore ed estensione ha il consenso di coloro che

volontariamente lasciano inserire il proprio profilo genetico

in banca dati?

15 maggio 2009

22

una considerazione

La legittimità di speculative searches e della possibilità di

sfruttare i vantaggi del family searching è messa in dubbio

anche dove risorse investigative come la comparazione

dei profili genetici e delle banche dati genetiche sono da

tempo ammesse e regolamentate

15 maggio 2009

23

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

UNA BANCA DATI DEL DNA A FINI

FORENSI è UN DATABASE IN CUI

PROFILI DI DNA, PROVENIENTI DA

FONTI DIVERSE, SONO

CONSERVATI A FINI DI

INVESTIGAZIONI FUTURE

15 maggio 2009

24

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

GLI SCOPI:

Cercare corrispondenze tra profili genetici

ottenuti dalla vittima o provenienti dalla

scena del crimine e profili genetici

contenuti nel database

15 maggio 2009

25

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

• Aprile, 1995: The Forensic Science Service istituisce il

primo database del DNA a fini forensi per l’Inghilterra ed

il Galles (NDNAD, National DNA Database)

- Attualmente il NDNAD contiene quasi 4 milioni di profili

genetici estratti da campioni biologici prelevati da sospettati o

da persone indagate o incriminate (The NDNAD Annual Report,

March, 2005);

- Cresce al tasso di 30000 profili genetici al mese;

- in un mese tipo, vengono trovate corrispondenze per circa 15

omicidi, 31 stupri, 330 furti d’auto (The NDNAD Annual Report,

July, 2003)

15 maggio 2009

26

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

• Ottobre, 1998: l’FBI apre il CODIS (Combined

Dna Index System), un Database federale che

riunisce circa 50 database nazionali

Some facts:

- Il CODIS contiene 170.000 profili genetici utili a fini

forensi e 4.782 profili genetici di autori di reati (FBI

Website);

- Il CODIS è ora il più grande database genetico a fini

investigativi del mondo;

- Fino ad ora il CODIS è stato impiegato in circa

77.700 indagini investigative

15 maggio 2009

27

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

• Molti altri paesi europei hanno già una banca dati

del DNA:

1997, Olanda e Austria;

1998, Germania

1999, Finlandia e Norvegia

2000, Danimarca, Svezia e Svizzera

.. L’Italia sta ancora aspettando

15 maggio 2009

28

Banche dati genetiche e familial

searching

Caso S e Marper vs UK (ECHR, 2008)

The first applicant, Mr S., was arrested on 19 January 2001 at the age of

eleven and charged with attempted robbery. His fingerprints and DNA

samples1 were taken. He was acquitted on 14 June 2001.

The second applicant, Mr Michael Marper, was arrested on 13 March 2001 and

charged with harassment of his partner. His fingerprints and DNA samples

were taken. Before a pre-trial review took place, he and his partner had

become reconciled, and the charge was not pressed. On 11 June 2001, the

Crown Prosecution Service served a notice of discontinuance on the

applicant's solicitors, and on 14 June the case was formally discontinued.

Both applicants asked for their fingerprints and DNA samples to be destroyed,

but in both cases the police refused. The applicants applied for judicial

review of the police decisions not to destroy the fingerprints and samples.

On 22 March 2002 the Administrative Court (Rose LJ and Leveson J)

rejected the application.

15 maggio 2009

29

Caso S e Marper vs UK (ECHR, 2008)

• The issue to be considered by the Court in this case was whether the

retention of the fingerprint and DNA data of the applicants, as persons who

had been suspected, but not convicted, of certain criminal offences, was

necessary in a democratic society. The Court noted that England, Wales and

Northern Ireland appeared to be the only jurisdictions within the Council of

Europe to allow the indefinite retention of fingerprint and DNA material of

any person of any age suspected of any recordable offence.

• It observed that the protection afforded by Article 8 of the Convention would

be unacceptably weakened if the use of modern scientific techniques in the

criminal-justice system were allowed at any cost and without carefully

balancing the potential benefits of the extensive use of such techniques

against important private-life interests.

• In conclusion, the Court found that the blanket and indiscriminate nature of

the powers of retention of the fingerprints, cellular samples and DNA profiles

of persons suspected but not convicted of offences, as applied in the case of

the present applicants, failed to strike a fair balance between the competing

public and private interests, and that the respondent State had overstepped

any acceptable margin of appreciation in this regard. Accordingly, the

retention in question constituted a disproportionate interference with the

applicants’ right to respect for private life and could not be regarded as

necessary

in a democratic society.

15 maggio 2009

30

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

..i pro

• Le banche dati del DNA possono aiutare gli investigatori in casi

che, senza questo strumento investigativo, rimarrebbero

probabilmente insoluti

• Le banche dati del DNA possono fornire soluzione a casi

irrisolti

• Le banche dati del DNA possono aiutare a scagionare persone

innocenti

15 maggio 2009

31

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

….e i contro

• I dati genetici possono rivelare informazioni sensibili sugli

individui, come stato di salute, razza, genere e altre caratteristiche

ereditarie

• Dato che i dati genetici sono condivisi all’interno del gruppo

biologico, possono rivelare informazioni sensibili anche su altre

persone

• Effettuare ricerche all’interno di una banca dati significa che di fatto

tutti gli individui i cui profili genetici sono inseriti in banca dati

sono periodicamente oggetto di comparazione con profili genetici

provenienti da scene del crimine

15 maggio 2009

32

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

Occorre trovare un bilanciamento tra ordine

pubblico e protezione dei diritti individuali

In tal senso i punti cruciali sono:

15 maggio 2009

33

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

1. Quali profili vengono inseriti in banca dati?

Chiunque sia sospettato o indagato per un reato (UK,

Austria, Germania);

Solo le persone condannate (USA, Olanda, Svezia)

15 maggio 2009

34

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

2. Per quali reati si viene inseriti in

banca dati?

Qualsiasi reato, anche minore (UK)

Solo alcuni tipi di reati (reati di tipo

sessuale, fatti di sangue, reati di droga)

(Austria, Germania, USA);

Reati puniti con pene superiori ad un certo

limite minimo (Olanda, Danimarca)

15 maggio 2009

35

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

3. Per quanto tempo i profili

devono/possono rimanere in banca dati?

Devono essere rimossi:

Solo gli indagati che sono stati assolti (UK, Austria,

USA);

Tutti in ogni caso dopo un certo numero di anni

(Olanda, Svezia)

Su richiesta (Switzerland)

D’ufficio (nella maggior parte degli altri paesi)

15 maggio 2009

36

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

4. Anonimato dei profili genetici e

identificazione

Separazione tra gli archivi dei profili genetici e gli

archivi anagrafici (la maggior parte dei paesi)

Conservazione congiunta dei profili genetici e dei dati

personali (Germania)

15 maggio 2009

37

BANCHE DATI DNA e diritti individuali

5. Conservazione dei campioni biologici

Distruzione immediata dei campioni biologici

Conservazione dei campioni per eventuali usi futuri

15 maggio 2009

38

D.D.L. 2042

adesione al trattato di PRUM

• Creazione di una banca dati del DNA ove saranno inseriti i

profili genetici di soggetti coinvolti in fatti di reato, profili

provenienti da scene del crimine, profili relativi a persone

scomparse e loro consanguinei

• Individuazione dei profili da inserire:

– Soggetti arrestati, fermati o in misura cautelare

– Soggetti condannati con sentenza definitiva

– Soggetti in misura di sicurezza

• Limitazione dei soggetti legittimati all’accesso e degli scopi

dello stesso

• Limite temporale massimo alla conservazione di profili (40 anni)

e campioni biologici (20 anni)

• Prelievo coattivo su indagati e anche su persone non iscritte nel

registro degli indagati

15 maggio 2009

39

PRUM CONVENTION, 27 May 2005

between the Kingdom of Belgium, the Federal Republic

of Germany, the Kingdom of Spain, the French

Republic, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the

Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Republic of

Austria on the stepping up of cross-border

cooperation, particularly in combating terrorism,

cross-border crime and illegal migration

15 maggio 2009

40

The PRUM Convention

Chapter 2

DNA profiles and fingerprinting and other data

Article 2

Establishment of national DNA analysis files

1. The Contracting Parties hereby undertake to open and keep national DNA analysis

files for the investigation of criminal offences. Processing of data kept in those files,

under this Convention, shall be carried out subject to its other provisions, in

compliance with the national law applicable to the processing.

2. For the purpose of implementing Convention, the Contracting Parties shall ensure the

availability of reference data from their national DNA analysis files as referred to in the

first sentence of paragraph 1. Reference data shall only include DNA profiles*

established from the non-coding part of DNA and a reference. Reference data must

not contain any data from which the data subject can be directly identified. Reference

data not traceable to any individual (untraceables) must be recognisable as such.

3. When depositing instruments of ratification, acceptance, approval or accession, each

Contracting Party shall specify the national DNA analysis files to which Articles 2 to 6

are applicable and the conditions for automated searching as referred to in Article

3(1).

* For the Federal Republic of Germany, DNA profiles as referred to in this Convention

shall mean DNA-Identifizierungsmuster (DNA identification patterns).

15 maggio 2009

41

The PRUM Convention

Article 3

Automated searching of DNA profiles

1. For the investigation of criminal offences, the Contracting Parties shall allow other

Contracting Parties' national contact points, as referred to in Article 6, access to the reference

data in their DNA analysis files, with the power to conduct automated searches by comparing

DNA profiles. Search powers may be exercised only in individual cases and in compliance

with the searching Contracting Party's national law.

2. Should an automated search show that a DNA profile supplied matches a DNA profile entered

in the Contracting Party's file searched, the searching contact point shall receive automated

notification of the hit and the reference. If no match can be found, automated notification of

this shall be given.

Article 4

Automated comparison of DNA profiles

1. For the investigation of criminal offences, the Contracting Parties shall, by mutual consent,

via their national contact points, compare the DNA profiles of their untraceables with all

DNA profiles from other national DNA analysis files' reference data. Profiles shall be

supplied and compared in automated form. DNA profiles of untraceables shall be supplied

for comparison only where provided for under the requesting Contracting Party's national law.

2. Should a Contracting Party, in the comparison referred to in paragraph 1, find that any

DNA profiles supplied match those in its DNA analysis file, it shall without delay supply the

other Contracting Party's national contact point with the reference data with which a match

has been found.

15 maggio 2009

42

Alcune raccomandazioni (Gene Watch Report, UK, 2005)

• Distruzione dei campioni di DNA (tranne quelli raccolti sulla scena del

crimine) una volta che l’indagine sia completata;

• Istituzione di autorità indipendenti per vigilare sulle applicazioni della

banca dati;

• Creazione di un “innocence Project” per correggere eventuali errori

giudiziari;

• Rimozione dalla banca dati dei profili degli individui prosciolti dalle

accuse

• Previsione di un termine massimo di conservazione

• Impossibilità di prelievo coatto di campioni biologici da individui non

indagati (es. persone offese)

15 maggio 2009

43

…un nuovo concetto di individuo?

The John Doe DNA warrant does not list a name. It describes only the suspect’s genetic profile

at 13 different locations (FBI standard) created from evidence at the crime scene.

This is used as a way to stop the clock on the statute limitations, according to which a criminal

matter has to be commenced within a certain time after the commission of the crime.

In 2000, shortly before the expiration of the six year statute of limitations, the Milwaukee County

District Attorney filed a case against Jon Doe #12, unknown male, by matching a DNA profile

listing the 13 genetic loci pertinent to the matching identification. John Doe was charged with

one count of kidnapping and for counts of first degree sexual assault.

Upon this data a circuit court judge issued an arrest warrant for John Doe #12, who was

described by his DNA profile.

One year after the Wisconsin State Crime Laboratory reported a “cold hit” (a match between a

profile from a convicted offender and a profile generated from evidence in case) out of the

Wisconsin DNA databank, between convicted offender Mr. Bobby Dabney and the DNA profile

described in the arrest warrant against John Doe #12. One month later the State of Wisconsin

filed an amended criminal complaint in which the defendant Dabney’s name took the place of

John Doe #12

Mr. Dabney was found guilty and sentenced to a sixty years prison-term. The defendant

appealed, arguing that the DNA arrest warrant was insufficient to confer personal jurisdiction.

The Court of Appeal for the 1st District denied the defendant’s motion. In judges’ opinion “for

the purpose of identifying a particular person, a DNA profile is arguable the most discrete,

exclusive means of personal identification possible”. Moreover the Court of Appeal affirmed that

a genetic code describes a person with far greater precision than physical description or name.

15 maggio 2009

44

“DNA profiling is the single most important advance in police investigation

techniques since the development of fingerprint classification systems in the

late nineteenth century. CrimTrac's new National Criminal Investigation DNA

Database will offer Australia's police services the enhanced ability to solve more

crimes more quickly.”

The CrimTrac Agency was established as an Executive Agency

under the Commonwealth Public Service Act in the AttorneyGeneral's portfolio on 1 July 2000. As head of the agency, the

Chief Executive Officer reports to the Federal Minister for Justice

and Customs, and the agency must comply with all

Commonwealth legislative, financial and administrative

arrangements.

The agency is underpinned by an Inter-Governmental Agreement

signed by all Australian police ministers. The Australasian Police

Ministers' Council is responsible for defining the agency's

strategic directions and key policies, setting of initiatives, and

appointing

15 maggio 2009members to the CrimTrac Board of Management.

45 The

board is generally responsible for the overall management of the

Tutela delle libertà individuali

O

Politica della sicurezza?

Tutela delle libertà individuali

È

Politica della sicurezza

15 maggio 2009

?

46

In ogni caso, la caratteristica di condivisione dei

dati genetici rende particolarmente delicata la

questione delle FAMILIAL SEARCHING

Tutte le garanzie previste dalla legge per I

soggetti indagati o imputati NON si applicano

tout court ai loro parenti, se questi non sono

ufficialmente inseriti in banca dati.

15 maggio 2009

47

![mutazioni genetiche [al DNA] effetti evolutivi [fetali] effetti tardivi](http://s1.studylibit.com/store/data/004205334_1-d8ada56ee9f5184276979f04a9a248a9-300x300.png)

![(Microsoft PowerPoint - PCR.ppt [modalit\340 compatibilit\340])](http://s1.studylibit.com/store/data/001402582_1-53c8daabdc15032b8943ee23f0a14a13-300x300.png)